The American Revolution and the German Bürgertum's Reassessment of America Virginia Sasser Delacey Old Dominion University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Schubert's Mature Operas: an Analytical Study

Durham E-Theses Schubert's mature operas: an analytical study Bruce, Richard Douglas How to cite: Bruce, Richard Douglas (2003) Schubert's mature operas: an analytical study, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4050/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Schubert's Mature Operas: An Analytical Study Richard Douglas Bruce Submitted for the Degree of PhD October 2003 University of Durham Department of Music A copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without their prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. 2 3 JUN 2004 Richard Bruce - Schubert's Mature Operas: An Analytical Study Submitted for the degree of Ph.D (2003) (Abstract) This thesis examines four of Franz Schubert's complete operas: Die Zwillingsbruder D.647, Alfonso und Estrella D.732, Die Verschworenen D.787, and Fierrabras D.796. -

1930S 1940 1941 1942

CLASS NOTES FOR MORE Incoming Correspondent: Floyd LaBarre Jr. 1930s Army captain, he was a science CLASS NEWS graduate with master’s from The 50 N. Hills Drive Hubert Vance Taylor ’35, Sorbonne in Paris and Kings Rising Sun, MD 21911-1663 For all class formerly of Decatur, Ga., died College London. He pioneered (443) 406-0296 (cell) news, photographs, June 2. He was 99 years old. Just radio and TV advertising, co- (410) 658-5024 (home) baby and wedding six months ago, he baptized two authoring Persuasion in Marketing: announcements, of his great-granddaughers, one The Dynamics of Marketing’s Great reunion planning the daughter of Kurt Rossetti ’90 Untapped Resource. Inducted into 1941 and more, go to and Elizabeth Irvin Rossetti, his the Market Research Hall of Fame community. granddaughter (photo below and in 1992, he was founder and chair Mayo Wills Lanning died lafayette.edu. online, Class of 1990 website). of Schwerin Research Corp. and June 22, a month after celebrating Click on “classes,” On Dec. 30, Taylor baptized also worked for Campbell’s Soup. his 97th birthday. Wife Trudy and then select Margot Jeanne Rossetti, born in Wife Enid survives him. predeceased him. A graduate of your class year. October 2012, daughter of Kurt ’90 Edward C. Helwick Jr. ’38, Washington (N.J.) High School and Elizabeth Irvin Rossetti, 96, Los Angeles, died May 26. A in 1935. A mining engineering Please continue to San Francisco, Calif.; and Caroline government and law graduate, he graduate, he worked for the New send updates to your Vance Pfeffer, born in August edited a humor magazine while Jersey Zinc Co. -

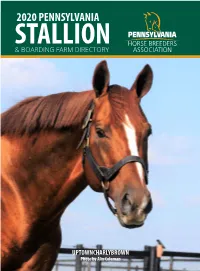

Online-2020-Stallion-Directory-File.Pdf

2020 PENNSYLVANIA STALLION & BOARDING FARM DIRECTORY UPTOWNCHARLYBROWN Photo by Alix Coleman 2020 PENNSYLVANIA STALLION & BOARDING FARM DIRECTORY Pennsylvania Horse Contents Breeders Association Pennsylvania, An Elite Breeding Program 4 Breeding Fund FAQ’s 6-7 Officers and Directors PA-Bred Earning Potential 8-9 President: Gregory C. Newell PE Stallion Roster 10-11 Vice President: Robert Graham Stallion Farm Directory 12-13 Secretary: Douglas Black Domicile Farm Directory 14-15 Treasurer: David Charlton Directors: Richard D. Abbott Front Cover Image: Uptowncharlybrown Elizabeth B. Barr Front Cover Photo Credit: Alix Coleman Glenn Brok Peter Giangiulio, Esq. Kate Goldenberg Roger E. Legg, Esq. PHBA Office Staff Deanna Manfredi Elizabeth Merryman Joanne Adams (Bookkeeper) Henry Nothhaft Jennifer Corado (Office Manager) Thomas Reigle Wendi Graham (Racing/Stallion Manager) Dr. Dale Schilling, VMD Jennifer Poorman (Graphic Designer) Charles Zachney Robert Weber (IT Manager) Executive Secretary: Brian N. Sanfratello Assistant Executive Secretary: Vicky Schowe Statistics provided herein are compiled by Pennsylvania Horse Contact Us Breeders Association from data supplied by Stallion and Farm Owners. Data provided or compiled generally is accurate, but 701 East Baltimore Pike, Suite E occasionally errors and omissions occur as a result of incorrect Kennett Square PA 19348 data received from others, mistakes in processing, and other Website: pabred.com causes. Phone: 610.444.1050 The PHBA disclaims responsibility for the consequences, if any, of Email: [email protected] such errors but would appreciate it being called to its attention. This publication will not be sold and can be obtained, at no cost, by visiting our website at www.pabred.com or contacting our office at 610.444.1050. -

'Deprived of Their Liberty'

'DEPRIVED OF THEIR LIBERTY': ENEMY PRISONERS AND THE CULTURE OF WAR IN REVOLUTIONARY AMERICA, 1775-1783 by Trenton Cole Jones A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland June, 2014 © 2014 Trenton Cole Jones All Rights Reserved Abstract Deprived of Their Liberty explores Americans' changing conceptions of legitimate wartime violence by analyzing how the revolutionaries treated their captured enemies, and by asking what their treatment can tell us about the American Revolution more broadly. I suggest that at the commencement of conflict, the revolutionary leadership sought to contain the violence of war according to the prevailing customs of warfare in Europe. These rules of war—or to phrase it differently, the cultural norms of war— emphasized restricting the violence of war to the battlefield and treating enemy prisoners humanely. Only six years later, however, captured British soldiers and seamen, as well as civilian loyalists, languished on board noisome prison ships in Massachusetts and New York, in the lead mines of Connecticut, the jails of Pennsylvania, and the camps of Virginia and Maryland, where they were deprived of their liberty and often their lives by the very government purporting to defend those inalienable rights. My dissertation explores this curious, and heretofore largely unrecognized, transformation in the revolutionaries' conduct of war by looking at the experience of captivity in American hands. Throughout the dissertation, I suggest three principal factors to account for the escalation of violence during the war. From the onset of hostilities, the revolutionaries encountered an obstinate enemy that denied them the status of legitimate combatants, labeling them as rebels and traitors. -

Annual Report 2019

FRAUNHOFER INSTITUTE FOR INTEGRATED SYSTEMS AND DEVICE TECHNOLOGY IISB Annual Report 2019 ANNUAL REPORT Fraunhofer Institute for Integrated Systems and Device Technology IISB Fraunhofer Institute for Integrated Systems and Device Technology 2019 Imprint Note to the Chapter „Names and Data“ Published by: The „Names and Data“ chapter is exclusively available in the online version of the annual report: Fraunhofer-Institut für Integrierte Systeme und Bauelementetechnologie IISB Schottkystrasse 10 https://www.iisb.fraunhofer.de/annual_reports 91058 Erlangen, Germany It includes the following contents: Editors: • Guest Scientists Thomas Richter • Patents Martin März • Publications • PhD Theses Layout and Setting: • Master Theses Anja Grabinger • Bachelor Theses Helen Kühn Thomas Richter Printed by: Frank UG Grafik – Druck – Werbung, Höchstadt Printed on: RecyStar® Nature, white, Recyclingpapier Cover Photo: Central power distribution for the ± 380 Volt DC network at Fraunhofer IISB. © Kurt Fuchs / Fraunhofer IISB Backside Photo: Acting director of Fraunhofer IISB Prof. Martin März explains to Bavarian Minister of Economic Affairs and Deputy Prime Minister Hubert Aiwanger (left) how sector coupling is implemented at Fraunhofer IISB and which significance the topic has for the Energiewende. © Kurt Fuchs / Fraunhofer IISB © Fraunhofer IISB, Erlangen 2020 All rights reserved. Reproduction only with express written authorization. ACHIEVEMENTS AND RESULTS ANNUAL REPORT 2019 FRAUNHOFER INSTITUTE FOR INTEGRATED SYSTEMS AND DEVICE TECHNOLOGY IISB Director (acting): Prof. Dr.-Ing. Martin März Fraunhofer IISB Schottkystrasse 10 91058 Erlangen, Germany Phone: +49 (0) 9131 761-0 Fax: +49 (0) 9131 761-390 E-Mail: [email protected] Web: www.iisb.fraunhofer.de PREFACE 2 Fraunhofer IISB Sustainable energy supply and mobility are key elements in meeting the im- 1 Schematic overview of the Headquarters minent environmental and economic challenges our society is facing. -

1. BURGHARD, Ramona 98 98 97 97 Schützenverein Breitenthal 390

Auswertung Finale LG Verein 1. BURGHARD, Ramona Schützenverein 390 Ringe Breitenthal 98 98 97 97 2. LUTZENBERGER, Stefan Schloßbergschützen 389 Ringe Aletshausen 1887 e,V, 98 97 97 97 3. KREUZER, Michaela Schützenverein 386 Ringe Breitenthal 98 97 96 95 4. SEITZ, Julia Schützenverein 386 Ringe Breitenthal 99 98 95 94 5. FENDT, Bernhard Schützenb, Krumbach 385 Ringe e,V, 97 96 96 96 6. KEPPELER, Gerhard SV Schützenblut e,V, 384 Ringe Balzhausen 97 96 96 95 7. WIEDEMANN, Thomas LichtenauMindelzell 384 Ringe 97 96 96 95 8. MAYER, Johannes S,Club 1881 383 Ringe Thannhausen e,V, 96 96 96 95 9. BRANDL, Annemarie Gemütlichkeit 382 Ringe Edenhausen 97 96 95 94 10. BLAU, Dominik LichtenauMindelzell 382 Ringe 97 96 95 94 11. STOHR, Reiner Schützenverein 381 Ringe Breitenthal 97 96 94 94 12. ROGG, Christian Hubertuss, 379 Ringe Haupeltshofen 95 95 95 94 13. MILLER, Guntram LichtenauMindelzell 378 Ringe 95 95 94 94 14. KREUZER, Christian Schützenverein 378 Ringe Breitenthal 96 95 94 93 15. HOFMANN, Otto LichtenauMindelzell 377 Ringe 95 95 94 93 16. SCHIEFELE, Matthias LichtenauMindelzell 375 Ringe 96 93 93 93 17. NIEDERREINER, Martin Alpenrose 375 Ringe Memmenhausen 96 94 93 92 18. WÖLFEL, Dominik Hubertuss, 375 Ringe Haupeltshofen 96 95 93 91 Verein 19. KOBER, Georg Schützenverein 375 Ringe Bleichen e,V, 97 94 93 91 20. FÖHR, Katharina Schützenverein 374 Ringe Breitenthal 95 94 94 91 21. DIETMAYER, Martin LichtenauMindelzell 372 Ringe 95 93 92 92 22. KNOLL, Alexander SV Schützenblut e,V, 372 Ringe Balzhausen 96 93 92 91 23. -

Motorrad: 3-Täler-Runde Beschreibung Kurzinfo Eine Schöne Tour Durch Das Herz Der Fränkischen Schweiz

Motorrad: 3-Täler-Runde Beschreibung Kurzinfo Eine schöne Tour durch das Herz der Fränkischen Schweiz. Von Gößweinstein aus Gößweinstein / Ortsmitte fahren Sie zuerst über die Hochfläche bis nach Obertrubach. Dort folgen Sie dem Mittel 770 m Trubachtal über Egloffstein bis nach Pretzfeld. Hier stoßen Sie auf das Wiesenttal, 67.3 km 290 m dem Sie über Ebermannstadt, Streitberg und Muggendorf bis nach Behringersmühle 02h:00min 544 m folgen. Sie bleiben auf der B470 und kommen in das Püttlachtal in Richtung Pottenstsein. Durch Pottenstein, vorbei an der Rodelbahn und dem Felsenbad sowie der Teufelshöhle folgen Sie dann der Straße Richtung Kirchenbirkig und biegen dort rechts ab, um wieder nach Gößweinstein zurückzukehren. Höhenprofil hm 600 600 500 500 400 400 300 300 200 200 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 km Länge: 67.2 km, Höchster Punkt: 544 m, Tiefster Punkt: 290 m Eine rechtliche Gewähr für die Richtigkeit des Inhalts kann nicht übernommen werden. Die Nutzung hat eigenverantwortlich zu erfolgen. © green-solutions | Exportiert am 04.03.2017 | Motorrad: 3-Täler-Runde Karte Eine rechtliche Gewähr für die Richtigkeit des Inhalts kann nicht übernommen werden. Die Nutzung hat eigenverantwortlich zu erfolgen. © green-solutions | Exportiert am 04.03.2017 | Motorrad: 3-Täler-Runde Interessante Plätze poi poi poi Burgstall Obertrubach Druidenhain Angelstelle Behringersmühle an der Püttlach 91286 Obertrubach 91346 Wiesenttal 91327 Gößweinstein 49.695215 N 49.786746 N +49 9242 357 11.349521 O 11.260134 O 49.781504 N 11.336625 O poi poi poi Angelstelle Streitberg an der Wiesent Kletter-Infozentrum Obertrubach Mühlen der Stadt 91346 Wiesenttal 91286 Obertrubach 91320 Ebermannstadt +49 9196 1292 +49 9245 9880 49.780391 N 11.183889 O 49.808011 N [email protected] 11.216075 O 49.691828 N 11.341989 O Eine rechtliche Gewähr für die Richtigkeit des Inhalts kann nicht übernommen werden. -

Kreistag Neu.Indd

Jede Wählerin und jeder Wähler hat 60 Stimmen. Keine Bewerberin und kein Bewerber darf mehr als 3 Stimmen erhalten, auch dann nicht, wenn sie oder er mehrfach aufgeführt sind. KeineJede BewerberinWählerinJedeJedeJede und WählerinundWählerin WählerinJede jeder keinJede Wählerin Wähler Bewerber undund und WählerinJede jederjeder jeder hat und Wählerin darfWähler60Wähler Wählerjederund Stimmen. mehr jeder Wählerund hathat hat als 60Wählerjeder60 603 Stimmen. hatStimmen.S Stimmen. timmenWähler 60 hat Stimmen. 60 erhalten,hat Stimmen. 60 Stimmen. auch dann nicht, wenn sie oder er mehrfach aufgeführt sind. Keine BewerberinKeineKeineKeine Bewerberin Bewerberinund KeineBewerberin keinKeine Bewerberin BewerberKeine Bewerberinundund und keinkein Bewerberinkein und darf BewerberBewerber Bewerber keinund mehr keinBewerber und als darfdarf darfBewerber 3kein S mehrmehr timmenmehr darfBewerber alsals alsmehrdarf 3erhalten,3 3 S Smehr Stimmenalsdarftimmentimmen 3 alsmehr Sauchtimmen erhalten,3erhalten, erhalten, Sals danntimmen 3 erhalten, S nicht,auchtimmenauch auch erhalten, dannwenndann dannauch erhalten, nicht, nicht,auchsie nicht,dann oder wenndannauchwenn nicht,wenn er nicht,mehrfachdannsiesie wennsie oderoder oder nicht,wenn sie erer aufgeführter oder mehrfachwennmehrfachsie mehrfach oderer sie mehrfach er sind.oder aufgeführtaufgeführt aufgeführtmehrfach er aufgeführtmehrfach sind. sind. aufgeführtsind. aufgeführtsind. sind. sind. Stimmzettel StimmzettelStimmzettelStimmzettelzurStimmzettel WahlStimmzettelStimmzettel desStimmzettel Kreistags -

Winterdienst Im Markt Neunkirchen A. Brand

34. Jahrgang www.neunkirchen-am-brand.de - 15. 03. 2006 Nr. 6 Winterdienst im Markt Neunkirchen a. Brand Liebe Mitbürgerinnen und Mitbürger, seit Jahrzehnten haben wir nicht mehr ein so lang andauerndes Winterwetter mit Kälte, Schnee und Glatteis erlebt. Es ist mir deshalb ein besonderes Anliegen, mich bei unse- ren Bauhofarbeitern für die bisher geleistete Schwerstarbeit beim Winterdienst sehr herzlich zu bedanken. Dieser Dienst beginnt regelmäßig bereits um 4.00 Uhr in der Frühe und dauert teilweise bis 22.00 Uhr am Abend. Weiterhin muss über alle Wochenenden und Feiertage ein Bereitschaftsdienst zur Verfügung stehen. Dieser Einsatz über diese lang anhaltende Zeitperiode geht über das übliche Maß hinaus, wel- ches normalerweise von unseren Mitarbeitern abverlangt wird. Die Anzahl der Einsatztage lag in diesem Winter um rund 30 % höher als im Durchschnitt der vergan- genen Jahre. Selbstverständlich ist es dem Winterdienst nicht möglich, alle Straßen und Wege gleich- zeitig zu räumen. Der Bauausschuss beschließt deshalb in jedem Jahr einen Räumplan, der die Prioritäten der zu räumenden Straßen und Wege festlegt. Unsere Mitarbeiter sind strikt angewiesen, sich an diesen Plan zu halten und können somit von sich aus keine Wünsche von Anliegern nach Räumung "ihrer" Straße nachkommen. Ich bitte hier- für um Ihr Verständnis und Ihre Nachsicht. Ihr Wilhelm Schmitt 1. Bürgermeister Bekanntmachungen der Amtliche Bekanntmachung Sperrung der Dachstadter Straße/ Baumgartenstraße in Marktgemeinde Ermreuth wegen Bauarbeiten Aufgrund witterungstechnischer Bedingungen verschiebt Bunter Seniorennachmittag sich der Beginn der Baumaßnahmen für die Instand- setzung der Brücke Dachstadter Straße/ Baumgartenstraße am Samstag, dem 1. April 2006 in Ermreuth auf den 20. März 2006. Sehr geehrte Seniorinnen und Senioren im Alter von 65 plus! Wir bitten Sie dies zu beachten. -

Guide to the Battles of Trenton and Princeton

Hidden Trenton Guide to the Battles of Trenton and Princeton Nine Days that Changed the World December 26, 1776 to January 3, 1777 A self-guided tour of the places and events that shaped the battles and changed the history of America Go to http://HiddenTrenton.com/BattleTour for links to online resources Updated 2017 Copyright © 2011, 2017 all rights reserved. The pdf file of this document may be distributed for non- commercial purposes over the Internet in its original, complete, and unaltered form. Schools and other non-profit educational institutions may print and redistribute sections of this document for classroom use without royalty. All of the illustrations in this document are either original creations, or believed by the author to be in the public domain. If you believe that you are the copyright holder of any image in this document, please con- tact the author via email at [email protected]. Forward I grew up in NJ, and the state’s 1964 Tricentennial cel- Recently, John Hatch, my friend and business partner, ebration made a powerful impression on me as a curious organized a “Tour of the Battle of Trenton” as a silent 4th grader. Leutez’ heroic portrait of Washington Cross- auction item for Trenton’s Passage Theatre. He used ing the Delaware was one of the iconic images of that Fischer’s book to research many of the stops, augmenting celebration. My only memory of a class trip to the park his own deep expertise concerning many of the places a year or two later, is peering up at the mural of Wash- they visited as one of the state’s top restoration architects. -

French and Hessian Impressions: Foreign Soldiers' Views of America During the Revolution

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2003 French and Hessian Impressions: Foreign Soldiers' Views of America during the Revolution Cosby Williams Hall College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Military History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Hall, Cosby Williams, "French and Hessian Impressions: Foreign Soldiers' Views of America during the Revolution" (2003). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626414. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-a7k2-6k04 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FRENCH AND HESSIAN IMPRESSIONS: FOREIGN SOLDIERS’ VIEWS OF AMERICA DURING THE REVOLUTION A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Cosby Hall 2003 a p p r o v a l s h e e t This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts CosbyHall Approved, September 2003 _____________AicUM James Axtell i Ronald Hoffman^ •h im m > Ronald S chechter TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Acknowledgements iv Abstract V Introduction 2 Chapter 1: Hessian Impressions 4 Chapter 2: French Sentiments 41 Conclusion 113 Bibliography 116 Vita 121 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The writer wishes to express his sincere appreciation to Professor James Axtell, under whose guidance this paper was written, for his advice, editing, and wisdom during this project. -

The Impact of Weather on Armies During the American War of Independence, 1775-1781 Jonathan T

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2011 The Force of Nature: The Impact of Weather on Armies during the American War of Independence, 1775-1781 Jonathan T. Engel Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES THE FORCE OF NATURE: THE IMPACT OF WEATHER ON ARMIES DURING THE AMERICAN WAR OF INDEPENDENCE, 1775-1781 By JONATHAN T. ENGEL A Thesis submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2011 The members of the committee approve the thesis of Jonathan T. Engel defended on March 18, 2011. __________________________________ Sally Hadden Professor Directing Thesis __________________________________ Kristine Harper Committee Member __________________________________ James Jones Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii This thesis is dedicated to the glory of God, who made the world and all things in it, and whose word calms storms. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Colonies may fight for political independence, but no human being can be truly independent, and I have benefitted tremendously from the support and aid of many people. My advisor, Professor Sally Hadden, has helped me understand the mysteries of graduate school, guided me through the process of earning an M.A., and offered valuable feedback as I worked on this project. I likewise thank Professors Kristine Harper and James Jones for serving on my committee and sharing their comments and insights.