Working Paper 142 Suresh Reddy May. 2018.P65

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Forest of Madhya Pradesh

Build Your Own Success Story! FOREST OF MADHYA PRADESH As per the report (ISFR) MP has the largest forest cover in the country followed by Arunachal Pradesh and Chhattisgarh. Forest Cover (Area-wise): Madhya Pradesh> Arunachal Pradesh> Chhattisgarh> Odisha> Maharashtra. Forest Cover (Percentage): Mizoram (85.4%)> Arunachal Pradesh (79.63%)> Meghalaya (76.33%) According to India State of Forest Report the recorded forest area of the state is 94,689 sq. km which is 30.72% of its geographical area. According to Indian state of forest Report (ISFR – 2019) the total forest cover in M.P. increased to 77,482.49 sq km which is 25.14% of the states geographical area. The forest area in MP is increased by 68.49 sq km. The first forest policy of Madhya Pradesh was made in 1952 and the second forest policy was made in 2005. Madhya Pradesh has a total of 925 forest villages of which 98 forest villages are deserted or located in national part and sanctuaries. MP is the first state to nationalise 100% of the forests. Among the districts, Balaghat has the densest forest cover, with 53.44 per cent of its area covered by forests. Ujjain (0.59 per cent) has the least forest cover among the districts In terms of forest canopy density classes: Very dense forest covers an area of 6676 sq km (2.17%) of the geograhical area. Moderately dense forest covers an area of 34, 341 sqkm (11.14% of geograhical area). Open forest covers an area of 36, 465 sq km (11.83% of geographical area) Madhya Pradesh has 0.06 sq km. -

Indigenous Knowledge of Local Communities of Malwa Region on Soil and Water Conservation

Int.J.Curr.Microbiol.App.Sci (2016) 5(2): 830-835 International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences ISSN: 2319-7706 Volume 5 Number 2(2016) pp. 830-835 Journal homepage: http://www.ijcmas.com Original Research Article doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.20546/ijcmas.2016.502.094 Indigenous Knowledge of Local Communities of Malwa Region on Soil and Water Conservation Manohar Pawar1*, Nitesh Bhargava2, Amit Kumar Uday3 and Munesh Meena3 Society for Advocacy & Reforms, 32 Shivkripa, SBI Colony, Dewas Road Ujjain, India *Corresponding author ABSTRACT After half a century of failed soil and water conservation projects in tropical K e yw or ds developing countries, technical specialists and policy makers are Malwa, reconsidering their strategy. It is increasingly recognised in Malwa region Indigenous, that the land users have valuable environmental knowledge themselves. This Soil and Water review explores two hypotheses: first, that much can be learned from Conservation previously ignored indigenous soil and water conservation practices; second, Article Info that can habitually act as a suitable starting point for the development of technologies and programmes. However, information on ISWC (Indigenous Accepted: 10 January 2016 Soil and Water Conservation) is patchy and scattered. Total 14 indigenous Available Online: Soil and water Conservation practises have been identified in the area. 10 February 2016 Result showed that these techniques were more suitable accord to geographic location. Introduction Soil and water are the basic resources and their interactions are major factors affecting these must be conserved as carefully as erosion-sedimentation processes. possible. The pressure of increasing population neutralizes all efforts to raise the The semi–arid regions with few intense standard of living, while loss of fertility in rainfall events and poor soil cover condition the soil itself nullifies the value of any produce more sediment per unit area. -

District Census Handbook, Satna, Part XIII-A, Series-11

lIltT XI1I-Cfi • • 1 ~. m. ~i, l I "fm(lq SI'~,,,f.f1fi ~"T i ~ iiJOIllVfff' I 'It-11' srnt I 1981 cENsas-PUBLlCATION PLAN (1981 Census Publi~Qtions, Series 11 in All India Series will be published in the following parts) GOVERNMENT OF INDIA PUBLICATIONS Part I-A Ad ministration Repo rt- Enumera tion Part I-B Administration Report-Tabulation P-art n ...:A General Population Tables Part U-B Primary Census Abstract Part 111 General Economic Tables Part IV Social and Cultural Tables Part V Migration Tables Part VI Fertility Tanles Part VII Tables on Houses and Disabled Population Part VIII Household Tables Part IX Special Tables on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes Part X-A Town Directory Part X-B . Survey Reports on selected Towns Part x-C Survey RepoFts on sele~ted Villages Part XI Ethnographic Notes and special studies on Schedultd Castes and Sched uled Tribes Part XTJ . Census Atlas Paper 1 of 1982 Primary Census Abstract for Sched~lled Castes and,Scheduled Tribes Paper 1 of 1984 HOllsehold Population by Religion of Head of Household STATE GOVERNMENT PUBLlCATIONS Part XIlI-A&B District Census Handbook for each of the 45 districts in the State. (Village and Town Directory and Primary Census Abstract) f~~~~ CONTENTS '{GQ W&I1T Pages 1 SIt"'fi"''' Foreword i-iv 2 sr,",,",,,, Preface v-vi 3 fiil~ "" ;mfT District Map 4 q~tCl1!.qf." Important Statistics vii 5 fcr~QV(rt~ fC!'tq'1'T Analytical Note ix-xnviii alfT~tI'T~l1Cfi fC'cqoit; ~,!~f"'ij' \ifTfij' ~T<:: ~~~f"{ij' Notes & Explanations; List of Scheduled ,;;r;:r~Tfu 'fir \I:"f1 ( «wTS"rr ) ~ fq~ll"'fi 1 9 76: Castes and Scheduled Tribes Order f::sr~T ~qlJ{;rT ~ftij''flT <fiT ~fij'~Ht IR"~ &i~ I (Amendment) Act, 1976. -

State Zone Commissionerate Name Division Name Range Name

Commissionerate State Zone Division Name Range Name Range Jurisdiction Name Gujarat Ahmedabad Ahmedabad South Rakhial Range I On the northern side the jurisdiction extends upto and inclusive of Ajaji-ni-Canal, Khodani Muvadi, Ringlu-ni-Muvadi and Badodara Village of Daskroi Taluka. It extends Undrel, Bhavda, Bakrol-Bujrang, Susserny, Ketrod, Vastral, Vadod of Daskroi Taluka and including the area to the south of Ahmedabad-Zalod Highway. On southern side it extends upto Gomtipur Jhulta Minars, Rasta Amraiwadi road from its intersection with Narol-Naroda Highway towards east. On the western side it extend upto Gomtipur road, Sukhramnagar road except Gomtipur area including textile mills viz. Ahmedabad New Cotton Mills, Mihir Textiles, Ashima Denims & Bharat Suryodaya(closed). Gujarat Ahmedabad Ahmedabad South Rakhial Range II On the northern side of this range extends upto the road from Udyognagar Post Office to Viratnagar (excluding Viratnagar) Narol-Naroda Highway (Soni ni Chawl) upto Mehta Petrol Pump at Rakhial Odhav Road. From Malaksaban Stadium and railway crossing Lal Bahadur Shashtri Marg upto Mehta Petrol Pump on Rakhial-Odhav. On the eastern side it extends from Mehta Petrol Pump to opposite of Sukhramnagar at Khandubhai Desai Marg. On Southern side it excludes upto Narol-Naroda Highway from its crossing by Odhav Road to Rajdeep Society. On the southern side it extends upto kulcha road from Rajdeep Society to Nagarvel Hanuman upto Gomtipur Road(excluding Gomtipur Village) from opposite side of Khandubhai Marg. Jurisdiction of this range including seven Mills viz. Anil Synthetics, New Rajpur Mills, Monogram Mills, Vivekananda Mill, Soma Textile Mills, Ajit Mills and Marsdan Spinning Mills. -

Territoires Infectés À La Date Du 7 Juillet 1960 — Infected Areas As on 7

— 308 Territoires infectés à la date du 7 juillet 1960 — Infected areas as on 7 July 1960 Notifications reçues aux termes du Règlement sanitaire Notifications received under the International Sanitary international concernant les circonscriptions infectées ou Regulations relating to infected local areas and to areas les territoires oà la présence de maladies guarantenaires in which the presence o f quarantinable diseases was a été signalée (voir page 167). reported (see page 167), ■ = Circonscriptions ou territoires notifiés aux termes de l’artide 3 • = Areas notified under Article 3 on the date indicated. à la date donnée. Autres territoires où la présence de maladies quarantenaires a été' Other areas in which the presence of quarantinable diseases was notifiée aux termes des articles 4, 5 et 9 a: notified under Articles 4, 5 and 9 (a): Â — pendant la période indiquée sous le nom de chaque maladie; A = during the period indicated under the heading of each disease; B = antérieurement à la période indiquée sous le nom de chaque B = prior to the period indicated under the heading of each maladie. disease. PESTE — PLAGXJE Andhra Pradesh, State FIEVRE JAUNE COTE D ’IVOIRE — IVORY COAST 19. VI-7 .VII East Godavari, District . ■ 28.XII.59 YELLOW FEVER Abengourou, Cercle. A 30.VI Guntur District .... ■ 31.XII.59 Abidjan, Cercle .... A 30.VI Amérique America Krishna, District .... ■ 27.VIII.59 io.iv-7.vn Agboville, Cercle .... A 23.VI Srikakulam, District . ■ ll.VI Bondoukou, Cercle . A 9.VI ÉQUATEUR — ECUADOR West Godavari, District . ■ 27,VIII.59 Afrique — Africa Bouaflé, Cercle............... A 23.VI Bouaké, Cercle .... -

District Disaster Management Plan Sidhi

District Disaster Management Plan Sidhi By Nishant Maheshwari (MBA-IIT Kanpur) MP School of Good Governance & Policy analysis In Consultation with School of Good Governance & Policy Analysis, Bhopal Seeds Technical Services Government of Madhya Pradesh District Administration, Sidhi District Disaster Management Plan [DDMP] Template Preface Sidhi Disaster Management Plan is a part of multi-level planning advocated by the Madhya Pradesh State Disaster Management Authority (MPSDMA) under DM Act of 2005 to help the District administration for effective response during the disaster. Sidhi is prone to natural as well as man- made disasters. Earthquake, Drought, Epidemic (Malaria) are the major Natural Hazards and forest fire, rail/ road accidents etc. are the main man-made disaster of the district. The Disaster Management plan includes facts and figures those have been collected from various departments. This plan is first attempt of the district administration and is a comprehensive document which contains various chapters and each chapter has its own importance. The plan consist Hazard & Risk Assessment, Institutional Mechanism, Response Mechanism, Standard Operating Procedure, inventory of Resources etc. Hazard & Risk Assessment is done on the basis of past thirty year disaster data & is collected from all departments. It is suggested that the District level officials of different department will carefully go through the plan and if have any suggestions & comments be free to convey the same so that same can be included in the next edition. It is hoped that the plan would provide concrete guidelines towards preparedness and quick response in case of an emergency and help in realizing sustainable Disaster Risk Reduction & mitigate/minimizes the losses in the district in the long run. -

Trajenffijfri[,.Try REGISTRAR GENERAL

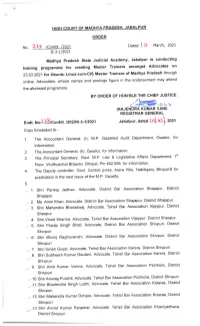

E±oH CouRT oF MADrTVA PRADESH, jABALP±±B ORDER Dated |0 March, 2021 NO. Confdl. 11-3-1/2021 Madhya Pradesh State Judicial Academy, Jabalpur is conducting training programme for creating Master Trainers amongst Advocates on 23.03.2021 for Ubuntu Linux-cum-CIS Master Trainers of Madhya Pradesh through online. Advocates, whose names and postings figure in the endorsement may attend the aforesaid programme. BY ORDER 0F HON'BLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE tRAjENffijfri[,.try REGISTRAR GENERAL Endt. No2.I.8/Confdl. /2020/11-3-1/2021 Jabalpur,dated.Ig|..Q3.},2021 Copy forwarded to:- 1. The Accountant General, (I), M.P. Gazetted Audit Department, Gwalior, for information. 2. The Accountant General, (ll), Gwalior, for information. 3. The Principal Secretary, Govt. M.P. Law & Legislative Affairs Department, 1st Floor, Vindhyachal Bhawan, Bhopal, Pin 462 006, for information. 4. The Deputy controller, Govt. Central press, Arera Hills, Habibganj, Bhopal-6 for publication in the next issue of the M.P. Gazette. 5. r,1. Shri Pankaj Jadhav, Advocate, District Bar Association Shajapur, District Shajapur 2. Ms. Amin Khan, Advocate, District Bar Association Shajapur, District Shajapur 3. Shri Mahendra Bharadwaj, Advocate, Tehsil Bar Association Vijaypur, District Sheopur 4. Shri Vinod Sharma, Advocate, Tehsil Bar Association Vijaypur, District Sheopur 5. Shri Pradip Singh Bhati, Advocate, District Bar Association Shivpuri, District Shivpuri + 6. Shri Monoj Raghuvanshi, Advocate, District Bar Association Shivpuri, District Shivpuri 7. Shri Girish Goyal, Advocate, Tehsil Bar Association Karera, District Shivpuri 8. Shri Subheem Kumar Gautam, Advocate, Tehsil Bar Association Karera, District '. shivpuri 9. Shri Amit Kumar Verma, Advocate, Tehsil Bar Association Pichhore, District Shivpuri gr 10. -

Government of India (Ministry of Tribal Affairs) Lok Sabha Unstarred Question No.†158 to Be Answered on 03.02.2020

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA (MINISTRY OF TRIBAL AFFAIRS) LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO.†158 TO BE ANSWERED ON 03.02.2020 INTEGRATED TRIBAL DEVELOPMENT PROJECT IN MADHYA PRADESH †158. DR. KRISHNA PAL SINGH YADAV: Will the Minister of TRIBAL AFFAIRS be pleased to state: (a) the details of the work done under Integrated Tribal Development Project in Madhya Pradesh during the last three years; (b) amount allocated during the last three years under Integrated Tribal Development Project; (c) Whether the work done under said project has been reviewed; and (d) if so, the outcome thereof? ANSWER MINISTER OF STATE FOR TRIBAL AFFAIRS (SMT. RENUKA SINGH SARUTA) (a) & (b): Under the schemes/programmes namely Article 275(1) of the Constitution of India and Special Central Assistance to Tribal Sub-Scheme (SCA to TSS), funds are released to State Government to undertake various activities as per proposals submitted by the respective State Government and approval thereof by the Project Appraisal Committee (PAC) constituted in this Ministry for the purpose. Funds under these schemes are not released directly to any ITDP/ITDA. However, funds are released to State for implementation of approved projects either through Integrated Tribal Development Projects (ITDPs)/Integrated Tribal Development Agencies (ITDAs) or through appropriate agency. The details of work/projects approved during the last three years under these schemes to the Government of Madhya Pradesh are given at Annexure-I & II. (c) & (d):The following steps are taken to review/ monitor the performance of the schemes / programmes administered by the Ministry: (i) During Project Appraisal Committee (PAC) meetings the information on the completion of projects etc. -

Ethnomedicinal Observations Among the Bheel and Bhilal Tribe of Jhabua District, Madhya Pradesh, India

Ethnobotanical Leaflets 14: 715-20, 2010. Ethnomedicinal Observations Among the Bheel and Bhilal Tribe of Jhabua District, Madhya Pradesh, India Vijay V. Wagh and Ashok. K. Jain School of Studies in Botany, Jiwaji University, Gwalior (Madhya Pradesh) [email protected] Issued: July 01, 2010 Abstract The paper highlights uses of 15 ethnomedicinal plants traditionally utilized by the Bheel and Bhilala tribes of Jhabua district. The plant species are used as herbal medicines for treatment of various ailments and healthcare. Keywords: Ethnomedicine; Jhabua district; tribal. Introduction Human culture has been augmented by plant and plant products since time immemorial. Perhaps ethnobiology is the first science that originated with the evaluation or existence of man on this planet. Natural products as medicines, although neglected in the recent past, are gaining popularity in the modern era. On a global scale, the current dependence on traditional medical system remain high, with a majority of world’s population still dependent on medicinal plants to fulfil most of their healthcare needs. Today, it is estimated that about 64 percent of the global population remain dependent on traditional medicines (Farnsworth 1994; Sindiga 1994). Nearly 8000 species of plants were recognized as of ethnobotanical importance (Anonymous 1994). Jhabua district is situated in the western most part of Madhya-Pradesh state. Most of the village inhabitants of Jhabua district belong to tribal communities. Major part of the district is covered by dense forest area in which various tribes, like Bheel, Bhilala and Pataya are living in majority. Out of these tribes Bheel and Bhilala stand high in strength, scattered in most of the villages of the district. -

2006-07 2006-07 2005-06 2004-05*** 2003-04 2002-03** 2001-02 2000-01 1999-00 1998-99 1997-98 PROFITABILITY Mn US$*

Mr. G. D. Birla and Mr. Aditya Birla, our founding fathers. We live by their values. Integrity, Commitment, Passion, Seamlessness and Speed M C M C Y K Y K Hindalco’s well-crafted growth and integration hinges on the three cornerstones of COST COMPETITIVENESS Reflected through its strong manufacturing base and operational efficiencies QUALITY Through its versatile range of products serving core applications for diverse industries; and Integrated Aluminium Complex Integrated Copper Complex Power Plant Aluminium Extrusions Plant GLOBAL REACH Bauxite Mines Coal Mines Aluminium Foil Plant Competing in markets across more Alumina Refineries Aluminium Wire Rod Aluminium Alloy Wheels Plant than 40 countries Aluminium Smelter Aluminium Rolled Products Plant R & D Centre Creating Superior Value The Hindalco story unfolds with the establishment of the Company in 1958, the commissioning of the aluminium facility at Renukoot in 1962 and the Renusagar Power Plant in 1967. Over the years, Hindalco has grown into the largest vertically integrated aluminium company in the country and among the largest primary producers of aluminium in Asia. Its copper smelter is today the world’s largest custom smelter at a single location. HINDALCO BUSINESS Share of Net Sales Value Rolled Products 14% Aluminium Extrusions Ingots & Billets 3% Conductor Redraw Rods Top Quartile of lowest cost 9% 5% Aluminium Foil, Alloy Aluminium producers globally Hydrate & Alumina Wheels & Others (Standard & Special) 5% 4% ALUMINIUM Primary Aluminium and Copper 40% registered on the London Metal SAP, DAP & Complexes, Precious Metals & Others Exchange 9% Concast Copper Rods COPPER 20% Star Trading House Status. 60% National Awards in Exports Copper Cathodes 31% M C M C Y K Y K HINDALCO – OUR VISION ALUMINIUM METAL PRODUCTION To be a premium metals major, global in size and reach, with a passionpassion forfor excellence.excellence. -

47270-001: Due Diligence Report on Social Safeguards

Due Diligence Report on Social Safeguard July 2014 IND: Madhya Pradesh District Connectivity Sector Project Sample Subprojects: 1. Chitrangi–Kasar Road 2. Dabra–Bhitawar–Harsi Road 3. Mahua–Chuwahi Road 4. Ujjain–Maksi Road Prepared by the Government of Madhya Pradesh through the Madhya Pradesh Road Development Corporation for the Asian Development Bank CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS Currency unit – Indian Rupees (INR) (as of June 6, 2014) INR1.00 = $ 0.01690 $1.00 = INR 59.0361 ABBREVIATIONS ADB - Asian Development Bank AP - Affected Person CPS - Country Partnership Strategy DP - Displaced Person DDR - due diligence report DPR - Detail Project Report EA - Executive Agency FYP - Five Year Plan GM - General Manager GOMP - Government of Madhya Pradesh GRC - Grievance Redress Committee GRM - Grievance Redress Mechanism HDI - Human Development Index MPRDC - Madhya Pradesh Road Development Corporation PPTA - Project Preparatory Technical Assistance RP - Resettlement Plan This due diligence report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section of this website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. PROJECT OVERVIEW ................................................................................................... 1 A. Project Background ..................................................................................................... 1 II. OBJECTIVES OF DUE DILIGENCE REPORT (DDR) ..................................................... 1 A. Methodology of due diligence ..................................................................................... -

Ecological Studies of the Amphibian Fauna and Their Distribution of Sidhi District (M.P.)

International Journal of Zoology Studies International Journal of Zoology Studies ISSN: 2455-7269; Impact Factor: RJIF 5.14 Received: 23-03-2020; Accepted: 25-04-2020; Published: 28-04-2020 www.zoologyjournals.com Volume 5; Issue 2; 2020; Page No. 27-30 Ecological studies of the amphibian fauna and their distribution of Sidhi district (M.P.) Balram Das1, Urmila Ahirwar2 1 Assistant Professor & Head, Department of Zoology, Govt. College, Amarpatan, Distt. Satna, Madhya Pradesh, India 2 Research Scholar, S.G.S. Govt. P.G. College, Sidhi, A.P.S. University, Rewa, Madhya Pradesh, India Abstract The amphibians was represented by 15 species belonging to 13 genera of 6 families and 2 orders from Sidhi district, Madhya Pradesh, India, during 2018 to 2019. Considering number of species in each family Bufonids with 2 species, Dicroglossids 5 species, Microhylids 2 species, Ranids 2 species, Rhacophorids 2 species and 2 species of Ichthyophids. The highest number of amphibian species was recorded from Gopad Banas tehsil (13 species), while the lowest number of species was observed in Sihawal tehsil (2 species). Status of amphibians shows that 5 species are abundant, 2 are common and 8 species are rare in the study sites. Keywords: Amphibian diversity, distribution, status, Sidhi district 1. Introduction distribution, habitat and status. This survey affords baseline The growing attention of populace in cities and the sizeable information and scientific facts for conservation of pace of development and growth of city areas have led to amphibians from arid zone. the emergence of unique prerequisites forming populations and communities, which range notably from the natural.