High Frequency Traders: Angels Or Devils?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Purple Circuit with Bill Kaiser Volume 9, Number 1 the SIDNEY MORRIS ISSUE

On The Purple Circuit With Bill Kaiser Volume 9, Number 1 THE SIDNEY MORRIS ISSUE WELCOME TO ON THE PURPLE CIRCUIT! An ongoing issue is censorship of the arts. CORPUS CHRISTI is an example with the outrageous imposition of a We exist to promote GLQBT theatre and performance fatwah against Terrence McNally after the London throughout the world and invite you to join in that endeavor! production. Also closer to home was the difficulty that Daylight Zone had in finding a space for their production- This is the Sidney Morris Issue. Sidney is one of our pioneer Kudos to Theatre Double in Philadelphia for providing space! Gay playwrights. Based in New York his plays are part of our culture and still available for production. While in poor health, Lastly I want to speak again about the treatment of he is still writing and has an important message for Playwrights. We would have no productions without them. I producers in his article DO US! in this issue. He also is the really feel that PC theatres have to be as responsible as first interviewee of my Oral History Project and I thank him straight ones about scripts. If you have a staff shortage-find for that (as well as Tom O'Neil who did the interview and Ty some volunteers to either read for you or send unsolicited Wilson who did the camerawork). scripts back in their SASEs in a reasonable length of time. I know that Producers have their share of woes too and we all As you know I believe in theatre and activism. -

View PDF File

LESBIAN, GAY, BISEXUAL, AND TRANSGENDER 2017 HERITAGE MONTH CITY OF LOS ANGELES LOS ANGELES CITY COUNCIL CULTURAL AFFAIRS Eric Garcetti Herb J. Wesson, Jr. COMMISSION Mayor District 10 Eric Paquette President Mike Feuer President Los Angeles City Attorney Gilbert Cedillo Charmaine Jefferson District 1 Ron Galperin Vice President Los Angeles City Controller Paul Krekorian Jill Cohen District 2 Thien Ho Bob Blumenfield Josefina Lopez District 3 Elissa Scrafano David Ryu John Wirfs District 4 Paul Koretz CITY OF LOS ANGELES District 5 DEPARTMENT OF Nury Martinez CULTURAL AFFAIRS District 6 Danielle Brazell Vacant General Manager District 7 Daniel Tarica Marqueece Harris-Dawson Assistant General Manager District 8 Will Caperton y Montoya Curren D. Price, Jr. Director of Marketing and Development District 9 Mike Bonin CALENDAR PRODUCTION District 11 Will Caperton y Montoya Mitchell Englander Editor and Art Director District 12 Marcia Harris Mitch O’Farrell PMAC District 13 Jose Huizar CALENDAR DESIGN District 14 Rubén Esparza, Red Studios Joe Buscaino PMAC District 15 Front Cover: Hector Silva, Los Novios, Pencil, colored pencil on 2 ply museum board, 22” x 28”, 2017 LESBIAN, GAY, BISEXUAL, AND TRANSGENDER 2017 HERITAGE MONTH ERIC GARCETTI MAYOR CITY OF LOS ANGELES Dear Friends, It is my pleasure to lead Los Angeles in celebrating Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Heritage Month and the immense contributions that our city’s LGBT residents make in the arts, academia, and private, public, and nonprofit sectors. I encourage Angelenos to take full advantage of this Calendar and Cultural Guide created by our Department of Cultural Affairs highlighting the many activities happening all over L.A. -

Kent Garvey Photographs, Circa 1970-2000 Coll2012-043

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8jq0zdp No online items Finding aid to the Kent Garvey photographs, circa 1970-2000 Coll2012-043 John Thompson, Kyle Morgan, and Loni Shibuyama ONE Archives at the USC Libraries, University of Southern California © 2012, revised 2021 909 West Adams Boulevard Los Angeles, California 90007 [email protected] URL: http://one.usc.edu Finding aid to the Kent Garvey Coll2012-043371 1 photographs, circa 1970-2000 Coll2012-043 Contributing Institution: ONE Archives at the USC Libraries, University of Southern California Title: Kent Garvey photographs Creator: Garvey, Kent Identifier/Call Number: Coll2012-043 Identifier/Call Number: 371 Physical Description: 5.9 Linear Feet7 boxes. Date (inclusive): 1970-2000 Abstract: Slides, contact sheets, negatives, photographic prints, and papers, circa 1970-2000, from photojournalist Kent Garvey, whose photographs appeared in gay and lesbian newspapers such as the Advocate and Update. Materials in the collection mostly document gay and lesbian events in California such as pride parades, chorus concerts, marching band performances, AIDS benefits, protest marches, gay athletic competitions, men's beauty pageants, drag, and fundraisers for LGBT organizations. Language of Material: English . Biographical / Historical Oren Kent Garvey was born in 1941. He was an independent photojournalist whose photographs in appeared in gay and lesbian newspapers such as Advocate and Update. He was also a member of the Great American Yankee (GAY) Freedom Band in the early 1980s. Garvey died in 2010. Access The collection is open to researchers. There are no access restrictions. Publication Rights All requests for permission to publish or quote from manuscripts must be submitted in writing to the ONE Archivist. -

Moffat Leads Baja Trip

^ SENTINEL Volume 20, Number'l l Foothill College, Los Altos Hills, CA 94022 January 13,1978 Moffat leads Baja trip By MICHAEL KEARNS a proboscis. This proboscis’ purpose looks ferocious, a Almost like clockwork thi territorial tool in fact, that time of year, a series of event actually hinders more than it take place that only a small per helps. He is an awewome, but centage of people ever get to see beautiful sight in any case. It’s up close. From late December tc sad to think these great creatures late March, wildlife activity a were formerly abundant as long the coast is at its peak far as Point Reyes, but were Elephant seals pup and hunted so extensively for their breed, gray whales bear their fine quality oil that they were young, sea lions swim and nearly exterminated. They are bask among the volcanic rocks easily aggravated during the and cliffs. In addition, migratory breeding season. Approaching shorebirds and waterfowl a- them at this time frigirtens them bound, plant life is often in and may result in crushing their bloom from the winter rains own pups. and killer whales and dolphins Oozing into San Ignacio Instructor Glen Moffat leads students on Baja marine wildlife tour. may be seen. Lagoon created a tremendous Recently, this writer had excitement among the passen the good fortune of joining gers. This is an outstanding Glenn Moffat (professor of biol breeding habitat for the gray ogy and ecology at Foothill), whale. These creatures are grace Student Sanchez wins and another Foothill student, ful giants, outsmarting us at Cathy Nau, for a trip that took every turn. -

DEPARTMENT of JUSTICE Robert F

DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE Robert F. Kennedy Department of Justice Building 950 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW., 20530, phone (202) 514–2000 http://www.usdoj.gov JEFFERSON B. SESSIONS III, Attorney General; born in Selma, AL; education: Huntingdon College, 1969; University of Alabama Law School, 1973; professional: Assistant U.S. Attorney, Southern District of Alabama, 1975–79; U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of Alabama, 1981–93, Attorney General of Alabama, 1995–97; U.S. Senator from Alabama, 1997–2017; sworn in as the 84th Attorney General of the United States on February 9, 2017 by Michael R. Pence. President Donald J. Trump announced his intention to nominate Mr. Sessions on November 18, 2016. OFFICE OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL RFK Main Justice Building, Room 5111, phone (202) 514–2001 Attorney General.—Jefferson B. Sessions III. Chief of Staff and Counselor to the Attorney General.—Joseph H. Hunt, Room 5115, 514–3893. Counselors to the Attorney General: Danielle Cutrona, Room 5110, 514–9665; Gustav Eyler, Room 5224, 514–4969; Alice LaCour, Room 5230, 514–9797; Brian Morrissey, Room 5214, 305–8674; Rachael Tucker, Room 5134, 616–7740. White House Liaison.—Mary Blanche Hankey, Room 5116, 353–4435. Director of Advance.—Vacant, Room 5127, 514–7281. Director of Scheduling.—Errical Bryant, Room 5133, 514–4195. Confidential Assistant.—Peggi Hanrahan, Room 5111, 514–2001. OFFICE OF THE DEPUTY ATTORNEY GENERAL RFK Main Justice Building, Room 4111, phone (202) 514–2101 Deputy Attorney General.—Rod J. Rosenstein, Room 4111. Principal Associate Deputy Attorney General.—Robert K. Hur, Room 4208, 514–2105. Chief of Staff and Associate Deputy Attorney General.—James A. -

The Barbara and Lawrence Fleischman Theater at the Getty Villa

The Barbara and Lawrence Fleischman Theater at the Getty Villa Thursdays–Saturdays, September 6–29, 2012 View of the Barbara and Lawrence Fleischman Theater and the entrance of the J. Paul Getty Museum at the Getty Villa Tonight’s performance is approximately ninety minutes long, without intermission. As a courtesy to our neighbors, we ask that you keep noise to a minimum while enjoying the production. Please refrain from unnecessarily loud or prolonged applause, shouting, whistling, or any other intrusive conduct during the performance. While exiting the theater and the Getty Villa, please do so quietly. The actors and stage managers employed in this production are members of Actors’ Equity Association, the Union of Professional Actors and Stage Managers in the United States. This theater operates under an agreement between the League of Resident Theatres and Actors’ Equity Association. Director Jon Lawrence Rivera is a member of the Society of Stage Directors and Choreographers (SDC), an independent national labor union. Adapted by Nick Salamone Directed by Jon Lawrence Rivera A new production by Playwrights’ Arena THE CAST Helen, queen of Sparta / Rachel Sorsa Menelaos, king of Sparta / Maxwell Caulfield Theoclymenus, ruler of Pharos / Chil Kong Theonoe, devotee of Artemis and sister of Theoclymenus / Natsuko Ohama Hattie, slave to Theoclymenus and Theonoe / Carlease Burke Lady, chorus / Melody Butiu Cleo, chorus / Arséne DeLay Cherry, chorus / Jayme Lake Old Soldier, follower of Menelaos / Robert Almodovar Teucer, younger brother of the Greek hero Ajax / Christopher Rivas Musicians / Brent Crayon, E. A., and David O Understudies / Anita Dashiell-Sparks, Robert Mammana, and Leslie Stevens THE COMPANY Producer / Diane Levine Associate Costume Designer / Byron Nora Composer and Musical Director / David O Costume Assistants / Wendell Carmichael Dramaturge / Mary Louise Hart and Taylor Moten Casting Directors / Russell Boast and Wardrobe Crew / Ellen L. -

Conference B Ooklet

Conference B o o k l e t _____________ 1 2 Welcome, to the participants of the 6th conference and the 10th anniversary of the European Forum for Restorative Justice to the city of Bilbao for a conference on restorative justice (RJ), on its current practices and future developments. We have this year the opportunity to enjoy this unique city, thanks to the generous hospitality of the Basque Government. After 10 exciting and fruitful years of RJ in Europe, many countries have now services of Victim Offender Mediation. Others are starting to work with RJ principles. The European Forum for Restorative Justice (EFRJ) has been instrumental for these developments through the implementations of several projects, publications and conferences. In the 6th biennial conference we celebrate 10 years of the European Forum and we launch for the first time a European Restorative Justice Award. This award is presented to a person or an organisation as recognition for their contribution to the development of RJ in Europe. In the light of important suggestions from our members we focus during this conference on themes involving the practitioners and the methods used in RJ. We would like to show the width and breadth of methods used throughout the continent. Several countries are presenting their way of doing RJ for the participants to become familiar with these different methods and to understand the reasons of their development. Over the years positive developments like Conferencing have taken place in the field of RJ. The EFRJ is currently implementing a research project that looks at the development and use of Conferencing in Europe and beyond. -

Falltheater and Dance

DADT ENDS WINDY CITY THE VOICE OF CHICAGO’S GAY, LESBIAN, BI AND TRANS COMMUNITY SINCE 1985 SEPT. 21, 2011 PAGES 4-8 TIMES VOL 26, NO. 50 www.WindyCityMediaGroup.com FALL THEATER AND DANCE A chill is in the air and a slate of new productions will heat up the stage this season, like Sweeney Todd at the Drury Lane (left, photo by Gregg PREVIEW Edelman), Natya Dance Theatre (center, photo by Amitava Sarkar) and Bailiwick’s Violet (right). Read about these and many more in this special Fall 2011 theater and dance preview issue. HALL OF FAME page 19 INDUCTEES NAMED PAGE 10 SUSAN WERNER INTERVIEW PAGE 30 GARDEN OF EVE PHOTOS Popular performer ‘Miss Ketty’ dies PAGE 39 BY JERRY NUNN The Association for Latino Men for Action gave Miss Ketty the ALMA Community Leadership Award in 1998. Ketty Teanga—known to many as Circuit nightclub regu- ALMA Board President Julio Rodriguez stated, “ALMA lar “Miss Ketty”—died Sept. 15 of kidney failure. She gave her the award for being a pioneer in the Latina was 64. trans community, because so many people had identified Teanga was born in Ecuador March 22, 1947. She moved her as someone who helped them get resources, espe- to New York City when she was about 16 before arriving cially because in those days, it was pretty dangerous. in Chicago during the ‘70s. She was largely known for She housed a lot of people, she did a lot of HIV/AIDS performing at Circuit Nightclub with the longest running education informally.” promotion the venue has had aptly named La Noche Loca She was recently crowned by Chicago’s Puerto Rican for 15 years. -

AAAI-2000 Frontmatter

From: AAAI-00 Proceedings. Copyright © 2000, AAAI (www.aaai.org). All rights reserved. Contents AAAI Organization / xix Conference Program Committees / xxi Outstanding Paper Award / xxiv Sponsoring Organizations / xxv Preface / xxvi Invited Talks / xxvii AAAI-2000 Technical Papers Agents Inter-Layer Learning Towards Emergent Cooperative Behavior / 3 Shawn Arseneau, Wei Sun, Changpeng Zhao, and Jeremy R. Cooperstock, McGill University Coordination Failure and Congestion in Information Networks / 9 A. M. Bell, NASA Ames Research Center; W. A. Sethares and J. A. Bucklew, University of Wisconsin-Madison Non-Deterministic Social Laws / 15 Michael H. Coen, MIT Artificial Intelligence Lab Solving Combinatorial Auctions Using Stochastic Local Search / 22 Holger H. Hoos, University of British Columbia; Craig Boutilier, University of Toronto A Mechanism for Group Decision Making in Collaborative Activity / 30 Luke Hunsberger, Harvard University; Massimo Zancanaro, ITC-irst Cobot in LambdaMOO: A Social Statistics Agent / 36 Charles Lee Isbell, Jr., Michael Kearns, Dave Kormann, Satinder Singh, and Peter Stone, AT&T Shannon Labs Semantics of Agent Communication Languages for Group Interaction / 42 Sanjeev Kumar, Marcus J. Huber, David R. McGee, and Philip R. Cohen, Oregon Graduate Institute; Hector J. Levesque, University of Toronto Deliberation in Equilibrium: Bargaining in Computationally Complex Problems / 48 Kate Larson and Tuomas Sandholm, Washington University An Algorithm for Multi-Unit Combinatorial Auctions / 56 Kevin Leyton-Brown, Yoav Shoham, and Moshe Tennenholtz, Stanford University Maintainability: A Weaker Stabilizability Like Notion for High Level Control / 62 Mutsumi Nakamura, University of Texas at Arlington; Chitta Baral, Arizona State University; Marcus Bjäreland, Linköping University Agent Capabilities: Extending BDI Theory / 68 Lin Padgham, RMIT University; Patrick Lambrix, Linköpings Universitet v Iterative Combinatorial Auctions: Theory and Practice / 74 David C. -

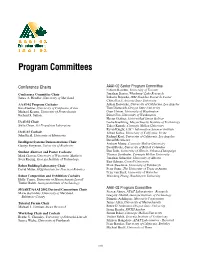

Program Committees

Program Committees Conference Chairs AAAI-02 Senior Program Committee Fahiem Bacchus, University of Toronto Conference Committee Chair Jonathan Baxter, Whizbang! Labs Research James A. Hendler, University of Maryland Roberto Bayardo, IBM Almaden Research Center Chitta Baral, Arizona State University AAAI-02 Program Cochairs Adnan Darwiche, University of California, Los Angeles Rina Dechter, University of California, Irvine Tom Dietterich, Oregon State University Michael Kearns, University of Pennsylvania Oren Etzioni, University of Washington Richard S. Sutton Dieter Fox, University of Washington Hector Geffner, Universidad Simon Bolivar IAAI-02 Chair Leslie Kaelbling, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Steve Chien, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Takeo Kanade, Carnegie Mellon University Kevin Knight, USC / Information Sciences Institute IAAI-02 Cochair Alfred Kobsa, University of California, Irvine John Riedl, University of Minnesota Richard Korf, University of California, Los Angeles David McAllester Intelligent Systems Demonstrations Chair Andrew Moore, Carnegie Mellon University George Ferguson, University of Rochester David Poole, University of British Columbia Student Abstract and Poster Cochairs Dan Roth, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign Mark Craven, University of Wisconsin, Madison Tuomas Sandholm, Carnegie Mellon University Sven Koenig, Georgia Institute of Technology Jonathan Schaeffer, University of Alberta Bart Selman, Cornell University Robot Building Laboratory Chair Mark Steedman, University of Edinburgh David Miller, -

Michael Kearns Papers Coll2008.009Coll2008-009

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt1j49r1g1 No online items Michael Kearns Papers Coll2008.009Coll2008-009 Michael C. Oliveira and Kyle Morgan Processing this collection has been funded by a generous grant from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission and the Council on Library and Information Resources. ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives, USC Libraries, University of Southern California 909 West Adams Boulevard Los Angeles, California 90007 (213) 821-2771 [email protected] URL: http://one.usc.edu Michael Kearns Papers Coll2008-009 1 Coll2008.009Coll2008-009 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives, USC Libraries, University of Southern California Title: Michael Kearns papers creator: Kearns, Michael Identifier/Call Number: Coll2008-009 Physical Description: 15.5 Linear Feet10 archive cartons, 6 archive boxes, 5 flat archive boxes, and 1 archive shoebox Date (inclusive): 1950-2014 Abstract: Clippings, flyers, manuscripts, photographs, programs, posters, scripts, and VHS videotapes of the works, theatrical performances, and appearances of Michael Kearns; a parent, playwright, producer, director, actor, author, and activist, who is openly gay and HIV-positive. Storage Unit: 11-14, 18 Storage Unit: 15-17, 19-21 Access The collection is open to researchers. There are no access restrictions. Publication Rights All requests for permission to publish or quote from manuscripts must be submitted in writing to the ONE Archivist. Permission for publication is given on behalf of ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives at USC Libraries as the owner of the physical items and is not intended to include or imply permission of the copyright holder, which must also be obtained. -

Get Used to It (1995 – )

For further study: LGBT TELEVISION PROGRAMMING: GET USED TO IT (1995 – ) COLLECTION Produced by the City of West Hollywood and airing on cable stations throughout the country, the public affairs talk show Get Used To It addresses national and local issues of interest to the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) community as well as allies. Hosted by California Senator Sheila James Kuehl, the first openly gay or lesbian person to be elected to the California Legislature, the program also highlights individuals whose lives and work have left a lasting legacy in the LGBT community. Issues examined by the series cover such topics as the gay civil rights movement, domestic violence, gay marriage and hate crimes. Interviewees have included activist Jean O’Leary, a founder of the Lesbian Feminist Liberation group, and Phill Wilson, founder and Executive Director of the Black AIDS Institute. The UCLA Film & Television Archive holds over 100 installments of this groundbreaking series from the year 1995 to the present, which are available for onsite research viewing. Installments of Get Used To It are added to the collection on a periodic basis. Please check with the Archive Research and Study Center (ARSC) for additional listings. For more information, or to arrange research viewing, please contact ARSC at (310) 206-5388, or by e-mail: [email protected] 1990s Get Used To It. Show No. 23: AIDS Today (1995-01). CityChannel 10. Host, Sheila James Kuehl. Guests, Mark Katz, Mary Lucey, Phill Wilson. The impact of AIDS on the gay community fifteen years after the disease was discovered.