Existing Conditions for Bicycling Report 2007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 4 DRAFT Bicycle Master Plan

Chapter 4: Design and Maintenance Guidance Chapter 4 provides recommended guidance on bicycle facility design and maintenance practices. It includes a discussion of the existing standards that guide street design in Bellingham followed by descriptions of bicycle facility types and intersection treatments that are new or uncommon in the City. Detailed design considerations including design guidance for travel lane widths, corner curb radii and wayfinding are presented in Appendix D. Public Works Development Guidelines and Improvement Standards Currently, street design in Bellingham is guided by the Public Works Development Guidelines and Improvements Standards, which were adopted in 2001. The guidelines contain provisions for development and improvement of bicycle facilities, including: standards signs, signals, and markings, roadway facilities, bicycle lanes, and bicycle parking.1 These design guidelines were developed based on the AASHTO Guide for the Development of Bicycle Facilities, the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD), and the Washington State Department of Transportation Design Manual. For local roadways, WSDOT instructs local jurisdictions to use the latest addition of the AASHTO Guide for the Development of Bicycle Facilities. It is recommended that the existing guidelines and the AASHTO Guide for the Development of Bicycle Facilities should continue to be used in the development of bicycle facilities. Those documents are not intended to be replaced by the guidance presented here; however, there are instances where additional guidance will be useful in implementing this Plan. This guidance is presented for consideration and possible integration into the Bellingham Public Works Development Guidelines and Improvements Standards. In all cases, the recommendations in this chapter are consistent with current Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) guidance and recommendations. -

Cargo Bikes As a Growth Area for Bicycle Vs. Auto Trips: Exploring the Potential for Mode Substitution Behavior

Transportation Research Part F 43 (2016) 48–55 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Transportation Research Part F journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/trf Cargo bikes as a growth area for bicycle vs. auto trips: Exploring the potential for mode substitution behavior William Riggs Department of City and Regional Planning, College of Architecture and Environmental Design, California Polytechnic State University, 1 Grand Ave., San Luis Obispo, CA 93405, United States article info abstract Article history: Cargo bikes are increasing in availability in the United States. While a large body of Received 26 February 2015 research continues to investigate traditional bike transportation, cargo bikes offer the Received in revised form 15 August 2016 potential to capture trips for those that might otherwise be made by car. Data from a sur- Accepted 18 September 2016 vey of cargo bike users queried use and travel dynamics with the hypothesis that cargo and Available online 6 October 2016 e-cargo bike ownership has the potential to contribute to mode substitution behavior. From a descriptive standpoint, 68.9% of those surveyed changed their travel behavior after Keywords: purchasing a cargo bike and the number of auto trips appeared to decline by 1–2 trips per Cargo bikes day, half of the auto travel prior to ownership. Two key reasons cited for this change Bicycles Linked trips include the ability to get around with children and more gear. Regression models that Mode choice underscore this trend toward increased active transport confirm this. Based on these results, further research could include focus on overcoming weather-related/elemental barriers, which continue to be an obstacle to every day cycling, and further investigation into families modeling healthy behaviors to children with cargo bikes. -

What to See in Portland Update2009

What to see in Portland, OR - by Marco Behrmann 07/02/2004 1/3 WHAT TO SEE IN PORTLAND , OR _________________________________________ Listed below you will find a couple of sights and my personal favourites to do in Portland. Since Portland was my town of exchange I do not know as many things about the other cities like Eugene, Corvallis, Ashland or La Grande. However, it would be just great if somebody could add tips about their places similar to the ones here, too! Please feel free to forward them to me (marcobehrmann[at]web.de ). I do not want you to believe that just because I stayed in Portland, and have many tips here for Portland, that a year at one of the other Oregon cities is not the same exciting. The tips listed here, however, are interesting for all Baden-Wuerttemberg students in Oregon, because many things you can already see and experience during your orientation weeks. (BTW: This is almost everything I did (among other things, of course) within my 2 ½ weeks of re-visiting in June 2004; but it took me a year of living in the city in 2001/02 to figure out which were the hot tips ☺) Here are my personal Must-Sees Oregon History Center in SW Park blocks right south of PSU (This museum features very interesting and well researched exhibitions about the development of Portland as a city as well as about the whole Pacific Northwest as it was discovered from the sea and the Columbia River; good place to check out during your orientation weeks; you get a student reduction with ISIC or other student ID card) Council Crest Park (considered the highest spot in Portland; nice views to Mt Hood, Mt Adams, Mt St Helens and even Mt Rainier on some days as well as to Beaverton; take Bus 51 [Vista]; the Bus driver often feels himself as an informal Portland guide; tell him that you are visiting and he even might stop for you at nice viewpoints to take pictures. -

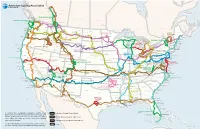

In Creating the Ever-Growing Adventure Cycling Route Network

Route Network Jasper Edmonton BRITISH COLUMBIA Jasper NP ALBERTA Banff NP Banff GREAT PARKS NORTH Calgary Vancouver 741 mi Blaine SASKATCHEWAN North Cascades NP MANITOBA WASHINGTON PARKS Anacortes Sedro Woolley 866 mi Fernie Waterton Lakes Olympic NP NP Roosville Seattle Twisp Winnipeg Mt Rainier NEW Elma Sandpoint Cut Bank NP Whitefish BRUNSWICK Astoria Spokane QUEBEC WASHINGTON Glacier Great ONTARIO NP Voyageurs Saint John Seaside Falls Wolf Point NP Thunder Bay Portland Yakima Minot Fort Peck Isle Royale Missoula Williston NOVA SCOTIA Otis Circle NORTHERN TIER NP GREEN MAINE Salem Hood Clarkston Helena NORTH DAKOTA 4,293 mi MOUNTAINS Montreal Bar Harbor River MONTANA Glendive Dickinson 380 mi Kooskia Butte Walker Yarmouth Florence Bismarck Fargo Sault Ste Marie Sisters Polaris Three Forks Theodore NORTH LAKES Acadia NP McCall Roosevelt Eugene Duluth 1,160 mi Burlington NH Bend NP Conover VT Brunswick Salmon Bozeman Mackinaw DETROIT OREGON Billings ADIRONDACK PARK North Dalbo Escanaba City ALTERNATE 395 mi Portland Stanley West Yellowstone 505 mi Haverhill Devils Tower Owen Sound Crater Lake SOUTH DAKOTA Osceola LAKE ERIE Ticonderoga Portsmouth Ashland Ketchum NM Crescent City NP Minneapolis CONNECTOR Murphy Boise Yellowstone Rapid Stillwater Traverse City Toronto Grand Teton 507 mi Orchards Boston IDAHO HOT SPRINGS NP City Pierre NEW MA Redwood NP NP Gillette Midland WISCONSIN Albany RI Mt Shasta 518 mi WYOMING Wolf Marine Ithaca YORK Arcata Jackson MINNESOTA Manitowoc Ludington City Ft. Erie Buffalo IDAHO Craters Lake Windsor Locks -

Bicycle Public Hearing Summary Report

BICYCLE PUBLIC HEARING SUMMARY REPORT DALLAS AND FORT WORTH DISTRICTS IN COORDINATION WITH NORTH CENTRAL TEXAS COUNCIL OF GOVERNMENTS OCTOBER 2014 Bicycle Public H earing October 2014 CONTENTS 1. PUBLIC HEARING SUMMARY AND ANALYSIS/RECOMMENDATIONS 2. PUBLIC HEARING COMMENT AND RESPONSE REPORT 3. PUBLIC HEARING POLL RESULTS 4. PUBLIC HEARING SURVEY RESULTS APPENDIX A. COPY OF WRITTEN COMMENTS B. COPY OF SURVEY RESULTS C. COPY OF ATTENDANCE SHEETS D. PUBLIC MEETING PHOTOS Bicycle Public H earing October 2014 1. PUBLIC HEARING SUMMARY AND ANALYSIS / RECOMMENDATIONS FOR: Texas Dept. Of Transportation (TxDOT), Dallas and Fort Worth Districts Annual Bicycle Public Hearing PURPOSE: To conduct a public hearing on transportation projects and programs that might affect bicycle use, in accordance with Title 43 of Texas Administrative Code, Subchapter D, §25.55 (b). PARTNERS: North Central Texas Council of Governments (NCTCOG) Public Hearing Format The bicycle public hearing agenda is as follows: (1) Open House 5:00 p.m. to 6:00 p.m (2) Welcome and Introductions 6:00 p.m. to 6:10 p.m. (a) Kathy Kleinschmidt, P.E., TxDOT Dallas District (3) Presentations 6:10 p.m. to 7:30 p.m. (a) State Bike Plan and Programs (i) Teri Kaplan – Statewide Bicycle Coordinator (b) Bicycle Policies and Projects (i) Kathy Kleinschmidt, P.E. – TxDOT Dallas District (ii) Phillip Hays, P.E. – TxDOT Fort Worth District (c) Regional Bicycle Programs and Projects (i) Karla Weaver, AICP – NCTCOG (4) Open House 7:30 p.m. to 8:00 p.m. Need and Purpose In accordance with Title 43 of Texas Administrative Code, Subchapter D, §25.55 (b) , a notice for the opportunity of a public hearing for transportation projects for bicycle use was published in the local newspapers for TxDOT’s Dallas and Fort Worth districts in April 2014. -

FHWA Bikeway Selection Guide

BIKEWAY SELECTION GUIDE FEBRUARY 2019 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave Blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED February 2019 Final Report 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5a. FUNDING NUMBERS Bikeway Selection Guide NA 6. AUTHORS 5b. CONTRACT NUMBER Schultheiss, Bill; Goodman, Dan; Blackburn, Lauren; DTFH61-16-D-00005 Wood, Adam; Reed, Dan; Elbech, Mary 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION VHB, 940 Main Campus Drive, Suite 500 REPORT NUMBER Raleigh, NC 27606 NA Toole Design Group, 8484 Georgia Avenue, Suite 800 Silver Spring, MD 20910 Mobycon - North America, Durham, NC 9. SPONSORING/MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) 10. SPONSORING/MONITORING AND ADDRESS(ES) AGENCY REPORT NUMBER Tamara Redmon FHWA-SA-18-077 Project Manager, Office of Safety Federal Highway Administration 1200 New Jersey Avenue SE Washington DC 20590 11. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES 12a. DISTRIBUTION/AVAILABILITY STATEMENT 12b. DISTRIBUTION CODE This document is available to the public on the FHWA website at: NA https://safety.fhwa.dot.gov/ped_bike 13. ABSTRACT This document is a resource to help transportation practitioners consider and make informed decisions about trade- offs relating to the selection of bikeway types. This report highlights linkages between the bikeway selection process and the transportation planning process. This guide presents these factors and considerations in a practical process- oriented way. It draws on research where available and emphasizes engineering judgment, design flexibility, documentation, and experimentation. 14. SUBJECT TERMS 15. NUMBER OF PAGES Bike, bicycle, bikeway, multimodal, networks, 52 active transportation, low stress networks 16. PRICE CODE NA 17. SECURITY 18. SECURITY 19. SECURITY 20. -

White Paper: Urban Application of Aerial Cableway Technology

WHITE PAPER: URBAN APPLICATION OF AERIAL CABLEWAY TECHNOLOGY WSP USA | June 2018 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY WSP USA is pleased to present the following white paper that summarizes the benefits and items for consideration of aerial cableway technology; outlines the project development process; and addresses advantages, costs and challenges associated with developing aerial cableway systems in urban environments. Urban applications of aerial cableway technology have been successfully integrated into transit networks in numerous cities around the globe, including the Portland Aerial Tram (Portland, Oregon) and Roosevelt Island Tram (New York, NY). Interest in aerial cableway technology has grown considerably in the United States in recent years, and initial feasibility studies have been completed in several U.S. cities, including San Diego, CA; Washington DC; and Brooklyn, NY. WSP is evaluating aerial cableway technology as an innovative first- and last-mile connection to regional transit in urban areas. Aerial cableway technology offers multiple benefits, including: relatively lower costs compared to other transportation modes, the ability to overcome significant changes in topography and other obstacles in natural and man-made environments, the ability to bypass congested roadways and transportation corridors, the ability to move high volumes of passengers: the equivalent of one city bus every minute, a streamlined design that fits into the urban environment, the potential to integrate transit-oriented development (TOD) near stations, and the ability to provide service between residential areas and key destinations. Many of these benefits have been realized in existing systems in La Paz, Bolivia, and Medellin, Colombia. Specifically, Medellin’s Line K transports more than 40,000 passengers per day between residential areas and the city center, reducing some commute times from more than an hour to approximately 10 minutes. -

Willy WATTS 14

VOLUME 4 BO. 3 <,JARTERLY JULY 1977 { Official Organ UNICYCLING SOCIETY OF AMERICA. Inc. c 1977 ~11 Rts Rea. Yearly Membership S5 Incl~des NeVl!lletter (4) ID Card - See Blank Pg.18 OFFICERS FELI.OW UNICYCLISTS: Due to o·trcwastances beyond our control (namely a big pile of dirt and construction lfOrk) the Southland Mall in Marion Pres. Paul Fox will not be available for our National Meet races on A.ug. 20. lttempts v.Pres. R.Tschudin to secure an alternate suita'Qle location nearby have failed. We are Sec. T. ni.ck Haines therefore planning to anit the Saturday morning races and utilize that FOUNDER M:El-!BE&S part of the day this year ror a general convention type get-together where clubs and inru.viduais can meet each other, swap ideas, and display Bernard Crandall their talents and cycles. · We still plan to hold the preliminary elimi Paul & Nancy Fox nations for the group an9- trick riding later in the day at the Catholic Peter Hangach High School parking lot·. We also have the use of the Coliseum again for Patricia Herron the Sunday afternoon final~. A pan.de is still in question and if we do Bill Jenack hold one it will be JllUCh s.horter than last year. It, is hoped that every Gordon Kruse member will make a ~ec~al-effort to attend the annual business meeting Steve McPeak Sunday rooming at th(' Hpltday Inn. We have a number of V9ry important Fr. Jas. J. Moran items on the agenda (see pag~ 14 for further infomation). -

Trends and Determinants of Cycling in the Washington, DC Region 6

Trends and Determinants of Cycling in the Washington, DC Region The Pennsylvania State University University of Maryland University of Virginia Virginia Polytechnic Institute & State University West Virginia University The Pennsylvania State University The Thomas D. Larson Pennsylvania Transportation Institute Transportation Research Building University Park, PA 16802-4710 Phone: 814-863-1909 Fax: 814-865-3930 1. Report No. VT-2009-05 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. Trends and Determinants of Cycling in the Washington, DC Region 6. Performing Organization Code Virginia Tech 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Ralph Buehler with Andrea Hamre, Dan Sonenklar, and Paul Goger 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) Virginia Tech, Urban Affairs and Planning, , Alexandria Center, 1021 Prince Street, Alexandria, VA 22314 11. Contract or Grant No. DTRT07-G-0003 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered US DOT Final Report, 08/2010-11/2011 Research & Innovative Technology Admin UTC Program, RDT-30 1200 New Jersey Ave., SE 14. Sponsoring Agency Code Washington, DC 20590 15. Supplementary Notes 16. Abstract This report analyzes cycling trends, policies, and commuting in the Washington, DC area. The analysis is divided into two parts. Part 1 focuses on cycling trends and policies in Washington (DC), Alexandria (VA), Arlington County (VA), Fairfax County (VA), Montgomery County (MD), and Prince George’s County (MD) during the last two decades. The goal is to gain a better understanding of variability and determinants of cycling within one metropolitan area. Data on bicycling trends and policies originate from official published documents, unpublished reports, site visits, and in-person, email, or phone interviews with transport planners and experts from municipal governments, regional planning agencies, and bicycling advocacy organizations. -

Bicycle Master Plan: 2012

BICYCLE MASTER PLAN: 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREPARED FOR V VISION STATEMENT VII EXECUTIVE SUMMARY IX CHAPTER 1 - INTRODUCTION 1 BICYCLING IN MESA 1 THE BENEFITS OF BICYCLING 3 BICYCLE TRIP AND RIDER CHARACTERISTICS 6 BICYCLE USE IN MESA 8 PAST BICYCLE PLANNING EFFORTS 12 REGIONAL PLANNING & COORDINATION EFFORTS 15 WHY MESA NEEDS AN UPDATED BICYCLE PLAN 20 PLAN UPDATE PROCESS AND PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT PROGRAM 23 CHAPTER 2 - GOALS & OBJECTIVES 25 PURPOSE OF GOALS AND OBJECTIVES 25 GOAL ONE 27 GOAL TWO 28 GOAL THREE 29 GOAL FOUR 30 GOAL FIVE 31 i CHAPTER 3 - EDUCATION, ENCOURAGEMENT, AND ENFORCEMENT 33 INTRODUCTION 33 MESARIDES! 34 EDUCATION 35 ENCOURAGEMENT 38 ENFORCEMENT 42 CHAPTER 4 - BICYCLE FACILITIES AND DESIGN OPTIONS 47 INTRODUCTION 47 BASIC ELEMENTS 48 WAYFINDING 52 BICYCLE PARKING DESIGN STANDARDS 53 BICYCLE ACCESSIBILITY 58 CHAPTER 5 - MESA’S BICYCLE NETWORK 61 INTRODUCTION 61 MESA’S NETWORK OF THE FUTURE 65 DEVELOPING A RECOMMENDED FUTURE NETWORK 68 METHODOLOGY TO IDENTIFY NEEDS 72 ii CHAPTER 6 - IMPLEMENTATION, EVALUATION, AND FUNDING 101 INTRODUCTION 101 IMPLEMENTATION STRATEGY 103 IMPLEMENTATION CRITERIA 104 PROJECT PRIORITY RANKING 105 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR PROGRAM EXPANSION 122 ADDITIONAL STAFF REQUIREMENTS 124 PERFORMANCE MEASUREMENT 125 SUMMARY 130 APPENDIX A - THE PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT PLAN PROCESS 131 PURPOSE OF THE PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT PLAN 131 PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT PROGRAM AND COMMUNITY INPUT PROCESS 132 BENEFITS OF THE PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT PROGRAM (PIP) 132 DEVELOPMENT OF THE PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT PROGRAM (PIP) PLAN 133 MESA BICYCLE -

Cycling: Supporting Economic Growth in Canada

Cycling: Supporting Economic Growth in Canada Prepared by Vélo Canada Bikes for the House of Commons Standing Committee on Finance pre-budget consultations Submitted August 3rd, 2018 1 Investing in cycling and active transportation: Supporting economic growth in Canada Recommendations for the Government of Canada In collaboration with provincial and territorial governments, the Federation of Canadian Municipalities, the Assembly of First Nations and additional stakeholders, implement the following recommendations: Recommendation #1: Develop a funding stream designed to rapidly increase the development and improvement of active transportation infrastructure and related traffic calming in all Canadian municipalities and in rural areas. Recommendation #2: Establish a national-level forum to consult, share, and develop a plan for moving more people and goods by bicycle in a wide variety of Canadian settings including urban, rural and remote communities. Recommendation #3: Direct Statistics Canada to collect data that will ensure the adequate and appropriate monitoring and reporting of the prevalence, potential and safety of cycling in Canadian municipalities. Use this data to set achievable evidence-based five- and ten-year transportation mode share targets for cycling. 2 Investment in bicycling represents a vastly underexploited opportunity for economic growth in Canada. If more Canadians were able to safely use a bicycle for daily transportation, there would be significant economic benefits including: a boost to economic productivity from a healthier and more productive workforce; improved mobility and personal savings for Canadians; disadvantaged groups could more easily gain skills and access employment opportunities and there would be an increase in business and tourism revenues. Increased cycling would also help to counter the negative economic costs that motorized vehicles impose on society in the form of congestion; road casualties; physical inactivity and poor health; pollution; and the political and environmental costs of maintaining fossil fuel supplies. -

Streetcar Plan Posters

WELCOME Welcome! The purpose of this open house is to present draft recommendations from the Bicycle Master Plan and the Streetcar System Plan to the public. City sta! and citizen volunteers are here to present the material and to answer questions. The room is divided into three sections: one for the Bicycle Master Plan, one for the Streetcar System Plan, and one called “Integration Station,” where we tie the two concepts together. Refreshments and child care services are also available. The bicycle and streetcar networks will play a key role in Portland’s future. Together, they will reduce reliance on the automobile for daily tasks, they will reinforce urban land use patterns, and they will help the City achieve its goals to combat climate change. This is the beginning of a transportation transformation. WHY PLAN? PORTLAND HAS A HISTORY OF SUCCESSFUL LONG-RANGE PLANNING In 1904, landscape architect John C. Olmsted produced a report for the City Among the parks that resulted from the Olmsted Plan are Holladay Park, Irving Parks Board. The plan served as a blueprint for development of the highly Park, Mt. Tabor (shown above), Overlook Park, Rocky Butte, Sellwood Park, valued park system we enjoy today. Washington Park, and several others. Interstate MAX Opened 2004 Airport MAX Hillsboro MAX Opened 2001 Opened 1998 Portland Streetcar Opened 2001 MAX to Gresham Opened 1986 Clackamas MAX Opens fall 2009 Westside Express Service Opened Feb. 2009 In 1989, three years after the "rst MAX line opened from downtown to Gresham, 20 years later the regional rail system is well on its way to being constructed as planners laid out a vision for a regional rail system.