A Genome-Wide Survey of Mutations in the Jurkat Cell Line Louis Gioia1* , Azeem Siddique2,Stevenr.Head2, Daniel R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

1 Metabolic Dysfunction Is Restricted to the Sciatic Nerve in Experimental

Page 1 of 255 Diabetes Metabolic dysfunction is restricted to the sciatic nerve in experimental diabetic neuropathy Oliver J. Freeman1,2, Richard D. Unwin2,3, Andrew W. Dowsey2,3, Paul Begley2,3, Sumia Ali1, Katherine A. Hollywood2,3, Nitin Rustogi2,3, Rasmus S. Petersen1, Warwick B. Dunn2,3†, Garth J.S. Cooper2,3,4,5* & Natalie J. Gardiner1* 1 Faculty of Life Sciences, University of Manchester, UK 2 Centre for Advanced Discovery and Experimental Therapeutics (CADET), Central Manchester University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Manchester Academic Health Sciences Centre, Manchester, UK 3 Centre for Endocrinology and Diabetes, Institute of Human Development, Faculty of Medical and Human Sciences, University of Manchester, UK 4 School of Biological Sciences, University of Auckland, New Zealand 5 Department of Pharmacology, Medical Sciences Division, University of Oxford, UK † Present address: School of Biosciences, University of Birmingham, UK *Joint corresponding authors: Natalie J. Gardiner and Garth J.S. Cooper Email: [email protected]; [email protected] Address: University of Manchester, AV Hill Building, Oxford Road, Manchester, M13 9PT, United Kingdom Telephone: +44 161 275 5768; +44 161 701 0240 Word count: 4,490 Number of tables: 1, Number of figures: 6 Running title: Metabolic dysfunction in diabetic neuropathy 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online October 15, 2015 Diabetes Page 2 of 255 Abstract High glucose levels in the peripheral nervous system (PNS) have been implicated in the pathogenesis of diabetic neuropathy (DN). However our understanding of the molecular mechanisms which cause the marked distal pathology is incomplete. Here we performed a comprehensive, system-wide analysis of the PNS of a rodent model of DN. -

Differential Patterns of Allelic Loss in Estrogen Receptor-Positive Infiltrating Lobular and Ductal Breast Cancer

GENES, CHROMOSOMES & CANCER 47:1049–1066 (2008) Differential Patterns of Allelic Loss in Estrogen Receptor-Positive Infiltrating Lobular and Ductal Breast Cancer L. W. M. Loo,1 C. Ton,1,2 Y.-W. Wang,2 D. I. Grove,2 H. Bouzek,1 N. Vartanian,1 M.-G. Lin,1 X. Yuan,1 T. L. Lawton,3 J. R. Daling,2 K. E. Malone,2 C. I. Li,2 L. Hsu,2 and P.L. Porter1,2,3* 1Division of Human Biology,Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center,Seattle,WA 2Division of Public Health Sciences,Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center,Seattle,WA 3Departmentof Pathology,Universityof Washington,Seattle,WA The two main histological types of infiltrating breast cancer, lobular (ILC) and the more common ductal (IDC) carcinoma are morphologically and clinically distinct. To assess the molecular alterations associated with these breast cancer subtypes, we conducted a whole-genome study of 166 archival estrogen receptor (ER)-positive tumors (89 IDC and 77 ILC) using the Affy- metrix GeneChip® Mapping 10K Array to identify sites of loss of heterozygosity (LOH) that either distinguished, or were shared by, the two phenotypes. We found single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of high-frequency LOH (>50%) common to both ILC and IDC tumors predominately in 11q, 16q, and 17p. Overall, IDC had a slightly higher frequency of LOH events across the genome than ILC (fractional allelic loss 5 0.186 and 0.156). By comparing the average frequency of LOH by chro- mosomal arm, we found IDC tumors with significantly (P < 0.05) higher frequency of LOH on 3p, 5q, 8p, 9p, 20p, and 20q than ILC tumors. -

Serum Albumin OS=Homo Sapiens

Protein Name Cluster of Glial fibrillary acidic protein OS=Homo sapiens GN=GFAP PE=1 SV=1 (P14136) Serum albumin OS=Homo sapiens GN=ALB PE=1 SV=2 Cluster of Isoform 3 of Plectin OS=Homo sapiens GN=PLEC (Q15149-3) Cluster of Hemoglobin subunit beta OS=Homo sapiens GN=HBB PE=1 SV=2 (P68871) Vimentin OS=Homo sapiens GN=VIM PE=1 SV=4 Cluster of Tubulin beta-3 chain OS=Homo sapiens GN=TUBB3 PE=1 SV=2 (Q13509) Cluster of Actin, cytoplasmic 1 OS=Homo sapiens GN=ACTB PE=1 SV=1 (P60709) Cluster of Tubulin alpha-1B chain OS=Homo sapiens GN=TUBA1B PE=1 SV=1 (P68363) Cluster of Isoform 2 of Spectrin alpha chain, non-erythrocytic 1 OS=Homo sapiens GN=SPTAN1 (Q13813-2) Hemoglobin subunit alpha OS=Homo sapiens GN=HBA1 PE=1 SV=2 Cluster of Spectrin beta chain, non-erythrocytic 1 OS=Homo sapiens GN=SPTBN1 PE=1 SV=2 (Q01082) Cluster of Pyruvate kinase isozymes M1/M2 OS=Homo sapiens GN=PKM PE=1 SV=4 (P14618) Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase OS=Homo sapiens GN=GAPDH PE=1 SV=3 Clathrin heavy chain 1 OS=Homo sapiens GN=CLTC PE=1 SV=5 Filamin-A OS=Homo sapiens GN=FLNA PE=1 SV=4 Cytoplasmic dynein 1 heavy chain 1 OS=Homo sapiens GN=DYNC1H1 PE=1 SV=5 Cluster of ATPase, Na+/K+ transporting, alpha 2 (+) polypeptide OS=Homo sapiens GN=ATP1A2 PE=3 SV=1 (B1AKY9) Fibrinogen beta chain OS=Homo sapiens GN=FGB PE=1 SV=2 Fibrinogen alpha chain OS=Homo sapiens GN=FGA PE=1 SV=2 Dihydropyrimidinase-related protein 2 OS=Homo sapiens GN=DPYSL2 PE=1 SV=1 Cluster of Alpha-actinin-1 OS=Homo sapiens GN=ACTN1 PE=1 SV=2 (P12814) 60 kDa heat shock protein, mitochondrial OS=Homo -

Association of Gene Ontology Categories with Decay Rate for Hepg2 Experiments These Tables Show Details for All Gene Ontology Categories

Supplementary Table 1: Association of Gene Ontology Categories with Decay Rate for HepG2 Experiments These tables show details for all Gene Ontology categories. Inferences for manual classification scheme shown at the bottom. Those categories used in Figure 1A are highlighted in bold. Standard Deviations are shown in parentheses. P-values less than 1E-20 are indicated with a "0". Rate r (hour^-1) Half-life < 2hr. Decay % GO Number Category Name Probe Sets Group Non-Group Distribution p-value In-Group Non-Group Representation p-value GO:0006350 transcription 1523 0.221 (0.009) 0.127 (0.002) FASTER 0 13.1 (0.4) 4.5 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006351 transcription, DNA-dependent 1498 0.220 (0.009) 0.127 (0.002) FASTER 0 13.0 (0.4) 4.5 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006355 regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent 1163 0.230 (0.011) 0.128 (0.002) FASTER 5.00E-21 14.2 (0.5) 4.6 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006366 transcription from Pol II promoter 845 0.225 (0.012) 0.130 (0.002) FASTER 1.88E-14 13.0 (0.5) 4.8 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006139 nucleobase, nucleoside, nucleotide and nucleic acid metabolism3004 0.173 (0.006) 0.127 (0.002) FASTER 1.28E-12 8.4 (0.2) 4.5 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006357 regulation of transcription from Pol II promoter 487 0.231 (0.016) 0.132 (0.002) FASTER 6.05E-10 13.5 (0.6) 4.9 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0008283 cell proliferation 625 0.189 (0.014) 0.132 (0.002) FASTER 1.95E-05 10.1 (0.6) 5.0 (0.1) OVER 1.50E-20 GO:0006513 monoubiquitination 36 0.305 (0.049) 0.134 (0.002) FASTER 2.69E-04 25.4 (4.4) 5.1 (0.1) OVER 2.04E-06 GO:0007050 cell cycle arrest 57 0.311 (0.054) 0.133 (0.002) -

WO 2019/079361 Al 25 April 2019 (25.04.2019) W 1P O PCT

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization I International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2019/079361 Al 25 April 2019 (25.04.2019) W 1P O PCT (51) International Patent Classification: CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DJ, DK, DM, DO, C12Q 1/68 (2018.01) A61P 31/18 (2006.01) DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, HN, C12Q 1/70 (2006.01) HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JO, JP, KE, KG, KH, KN, KP, KR, KW, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, (21) International Application Number: MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, PCT/US2018/056167 OM, PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, (22) International Filing Date: SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, 16 October 2018 (16. 10.2018) TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. (25) Filing Language: English (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, (26) Publication Language: English GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, ST, SZ, TZ, (30) Priority Data: UG, ZM, ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, RU, TJ, 62/573,025 16 October 2017 (16. 10.2017) US TM), European (AL, AT, BE, BG, CH, CY, CZ, DE, DK, EE, ES, FI, FR, GB, GR, HR, HU, ΓΕ , IS, IT, LT, LU, LV, (71) Applicant: MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF MC, MK, MT, NL, NO, PL, PT, RO, RS, SE, SI, SK, SM, TECHNOLOGY [US/US]; 77 Massachusetts Avenue, TR), OAPI (BF, BJ, CF, CG, CI, CM, GA, GN, GQ, GW, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139 (US). -

Supplementary Table S4. FGA Co-Expressed Gene List in LUAD

Supplementary Table S4. FGA co-expressed gene list in LUAD tumors Symbol R Locus Description FGG 0.919 4q28 fibrinogen gamma chain FGL1 0.635 8p22 fibrinogen-like 1 SLC7A2 0.536 8p22 solute carrier family 7 (cationic amino acid transporter, y+ system), member 2 DUSP4 0.521 8p12-p11 dual specificity phosphatase 4 HAL 0.51 12q22-q24.1histidine ammonia-lyase PDE4D 0.499 5q12 phosphodiesterase 4D, cAMP-specific FURIN 0.497 15q26.1 furin (paired basic amino acid cleaving enzyme) CPS1 0.49 2q35 carbamoyl-phosphate synthase 1, mitochondrial TESC 0.478 12q24.22 tescalcin INHA 0.465 2q35 inhibin, alpha S100P 0.461 4p16 S100 calcium binding protein P VPS37A 0.447 8p22 vacuolar protein sorting 37 homolog A (S. cerevisiae) SLC16A14 0.447 2q36.3 solute carrier family 16, member 14 PPARGC1A 0.443 4p15.1 peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, coactivator 1 alpha SIK1 0.435 21q22.3 salt-inducible kinase 1 IRS2 0.434 13q34 insulin receptor substrate 2 RND1 0.433 12q12 Rho family GTPase 1 HGD 0.433 3q13.33 homogentisate 1,2-dioxygenase PTP4A1 0.432 6q12 protein tyrosine phosphatase type IVA, member 1 C8orf4 0.428 8p11.2 chromosome 8 open reading frame 4 DDC 0.427 7p12.2 dopa decarboxylase (aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase) TACC2 0.427 10q26 transforming, acidic coiled-coil containing protein 2 MUC13 0.422 3q21.2 mucin 13, cell surface associated C5 0.412 9q33-q34 complement component 5 NR4A2 0.412 2q22-q23 nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, member 2 EYS 0.411 6q12 eyes shut homolog (Drosophila) GPX2 0.406 14q24.1 glutathione peroxidase -

Pan-Cancer Analysis of Homozygous Deletions in Primary Tumours Uncovers Rare Tumour Suppressors

Corrected: Author correction; Corrected: Author correction ARTICLE DOI: 10.1038/s41467-017-01355-0 OPEN Pan-cancer analysis of homozygous deletions in primary tumours uncovers rare tumour suppressors Jiqiu Cheng1,2, Jonas Demeulemeester 3,4, David C. Wedge5,6, Hans Kristian M. Vollan2,3, Jason J. Pitt7,8, Hege G. Russnes2,9, Bina P. Pandey1, Gro Nilsen10, Silje Nord2, Graham R. Bignell5, Kevin P. White7,11,12,13, Anne-Lise Børresen-Dale2, Peter J. Campbell5, Vessela N. Kristensen2, Michael R. Stratton5, Ole Christian Lingjærde 10, Yves Moreau1 & Peter Van Loo 3,4 1234567890 Homozygous deletions are rare in cancers and often target tumour suppressor genes. Here, we build a compendium of 2218 primary tumours across 12 human cancer types and sys- tematically screen for homozygous deletions, aiming to identify rare tumour suppressors. Our analysis defines 96 genomic regions recurrently targeted by homozygous deletions. These recurrent homozygous deletions occur either over tumour suppressors or over fragile sites, regions of increased genomic instability. We construct a statistical model that separates fragile sites from regions showing signatures of positive selection for homozygous deletions and identify candidate tumour suppressors within those regions. We find 16 established tumour suppressors and propose 27 candidate tumour suppressors. Several of these genes (including MGMT, RAD17, and USP44) show prior evidence of a tumour suppressive function. Other candidate tumour suppressors, such as MAFTRR, KIAA1551, and IGF2BP2, are novel. Our study demonstrates how rare tumour suppressors can be identified through copy number meta-analysis. 1 Department of Electrical Engineering (ESAT) and iMinds Future Health Department, University of Leuven, Kasteelpark Arenberg 10, B-3001 Leuven, Belgium. -

Supplementary Data

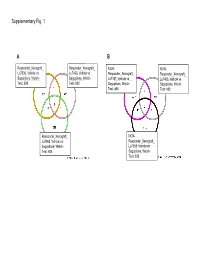

Supplementary Fig. 1 A B Responder_Xenograft_ Responder_Xenograft_ NON- NON- Lu7336, Vehicle vs Lu7466, Vehicle vs Responder_Xenograft_ Responder_Xenograft_ Sagopilone, Welch- Sagopilone, Welch- Lu7187, Vehicle vs Lu7406, Vehicle vs Test: 638 Test: 600 Sagopilone, Welch- Sagopilone, Welch- Test: 468 Test: 482 Responder_Xenograft_ NON- Lu7860, Vehicle vs Responder_Xenograft_ Sagopilone, Welch - Lu7558, Vehicle vs Test: 605 Sagopilone, Welch- Test: 333 Supplementary Fig. 2 Supplementary Fig. 3 Supplementary Figure S1. Venn diagrams comparing probe sets regulated by Sagopilone treatment (10mg/kg for 24h) between individual models (Welsh Test ellipse p-value<0.001 or 5-fold change). A Sagopilone responder models, B Sagopilone non-responder models. Supplementary Figure S2. Pathway analysis of genes regulated by Sagopilone treatment in responder xenograft models 24h after Sagopilone treatment by GeneGo Metacore; the most significant pathway map representing cell cycle/spindle assembly and chromosome separation is shown, genes upregulated by Sagopilone treatment are marked with red thermometers. Supplementary Figure S3. GeneGo Metacore pathway analysis of genes differentially expressed between Sagopilone Responder and Non-Responder models displaying –log(p-Values) of most significant pathway maps. Supplementary Tables Supplementary Table 1. Response and activity in 22 non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) xenograft models after treatment with Sagopilone and other cytotoxic agents commonly used in the management of NSCLC Tumor Model Response type -

S1 Table Protein

S1 Table dFSHD12_TE dFSHD12_NE aFSHD51_TE aFSHD51_NE Accession Gene Protein H/L SD # bold H/L SD # bold H/L SD # bold H/L SD # bold Intermediate filament (or associated proteins) P17661 DES Desmin 0.91 N.D. 37 1.06 1.35 19 0.89 1,13 33 * 1.20 1.21 17 * P02545 LMNA Prelamin-A/C 0.90 1.25 30 * 1.07 1.26 20 0.96 1.23 34 1.21 1.24 19 * P48681 NES Nestin 0.91 N.D. 60 0.94 1.25 27 0.72 1.20 50 * 0.89 1.27 31 * P08670 VIM Vimentin 1.04 N.D. 35 1.24 1.24 14 * 1.21 1.18 36 * 1.39 1.17 16 * Q15149 PLEC Plectin-1 1.10 1.28 19 1.05 1.10 3 1.07 1.23 26 1.25 1.27 7 * P02511 CRYAB Alpha-crystallin B chain (HspB5) 1.47 1.17 2 1.17 2 1.14 1.12 2 Tubulin (or associated proteins) P62158 CALM1 Calmodulin (CaM) 0.83 0.00 1 0.93 0.00 1 Programmed cell death 6- Q8WUM4 PDCD6IP 1.34 0.00 1 interacting protein Q71U36 TUBA1A Tubulin α-1A chain (α-tubulin 3) 1.44 1.12 3 * Tubulin β chain (Tubulin β-5 P07437 TUBB 1.52 0.00 1 chain) Nuclear mitotic apparatus Q14980 NUMA1 0.68 0.00 1 0.75 0.00 1 protein 1 Microtubule-associated protein P27816 MAP4 1.10 1 4 Microtubule-associated protein P78559 MAP1A 0.76 0.00 1 1A Q6PEY2 TUBA3E Tubulin α-3E chain (α-tubulin 3E) 0.91 0.00 1 1.12 0.00 1 0.98 1.12 3 Tubulin β-2C chain (Tubulin β-2 P68371 TUBB2C 0.93 1.13 7 chain) Q3ZCM7 TUBB8 Tubulin β-8 chain 0.97 1.09 4 Serine P34897 SHMT2 hydroxymethyltransferase 0.93 0.00 1 (serine methylase) Cytoskeleton-associated protein Q07065 CKAP4 0.98 1.24 5 0.96 0.00 1 1.08 1.28 6 0.75 0.00 1 4 (p63) Centrosomal protein of 135 kDa Q66GS9 CEP135 0.84 0.00 1 (Centrosomal protein 4) Pre-B cell leukemia transcription Q96AQ6 PBXIP1 0.74 0.00 1 0.80 1 factor-interacting protein 1 T-complex protein 1 subunit P17897 TCP1 0.84 0.00 1 alpha (CCT-alpha) Cytoplasmic dynein Q13409 DYNC1I2 1.01 0.00 1 intermediate chain 2 (DH IC-2) Dynein heavy chain 3 (Dnahc3- Q8TD57 DNAH3 b) Microtubule-actin cross- linking Q9UPN3 MACF1 factor 1 (Trabeculin-alpha) Actin (or associated including myofibril-associated porteins) P60709 ACTB Actin, cytoplasmic 1 (β-actin) 1.11 N.D. -

Original Article a Database and Functional Annotation of NF-Κb Target Genes

Int J Clin Exp Med 2016;9(5):7986-7995 www.ijcem.com /ISSN:1940-5901/IJCEM0019172 Original Article A database and functional annotation of NF-κB target genes Yang Yang, Jian Wu, Jinke Wang The State Key Laboratory of Bioelectronics, Southeast University, Nanjing 210096, People’s Republic of China Received November 4, 2015; Accepted February 10, 2016; Epub May 15, 2016; Published May 30, 2016 Abstract: Backgrounds: The previous studies show that the transcription factor NF-κB always be induced by many inducers, and can regulate the expressions of many genes. The aim of the present study is to explore the database and functional annotation of NF-κB target genes. Methods: In this study, we manually collected the most complete listing of all NF-κB target genes identified to date, including the NF-κB microRNA target genes and built the database of NF-κB target genes with the detailed information of each target gene and annotated it by DAVID tools. Results: The NF-κB target genes database was established (http://tfdb.seu.edu.cn/nfkb/). The collected data confirmed that NF-κB maintains multitudinous biological functions and possesses the considerable complexity and diversity in regulation the expression of corresponding target genes set. The data showed that the NF-κB was a central regula- tor of the stress response, immune response and cellular metabolic processes. NF-κB involved in bone disease, immunological disease and cardiovascular disease, various cancers and nervous disease. NF-κB can modulate the expression activity of other transcriptional factors. Inhibition of IKK and IκBα phosphorylation, the decrease of nuclear translocation of p65 and the reduction of intracellular glutathione level determined the up-regulation or down-regulation of expression of NF-κB target genes. -

Bioinformatics Analysis for the Identification of Differentially Expressed Genes and Related Signaling Pathways in H

Bioinformatics analysis for the identification of differentially expressed genes and related signaling pathways in H. pylori-CagA transfected gastric cancer cells Dingyu Chen*, Chao Li, Yan Zhao, Jianjiang Zhou, Qinrong Wang and Yuan Xie* Key Laboratory of Endemic and Ethnic Diseases , Ministry of Education, Guizhou Medical University, Guiyang, China * These authors contributed equally to this work. ABSTRACT Aim. Helicobacter pylori cytotoxin-associated protein A (CagA) is an important vir- ulence factor known to induce gastric cancer development. However, the cause and the underlying molecular events of CagA induction remain unclear. Here, we applied integrated bioinformatics to identify the key genes involved in the process of CagA- induced gastric epithelial cell inflammation and can ceration to comprehend the potential molecular mechanisms involved. Materials and Methods. AGS cells were transected with pcDNA3.1 and pcDNA3.1::CagA for 24 h. The transfected cells were subjected to transcriptome sequencing to obtain the expressed genes. Differentially expressed genes (DEG) with adjusted P value < 0.05, | logFC |> 2 were screened, and the R package was applied for gene ontology (GO) enrichment and the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis. The differential gene protein–protein interaction (PPI) network was constructed using the STRING Cytoscape application, which conducted visual analysis to create the key function networks and identify the key genes. Next, the Submitted 20 August 2020 Kaplan–Meier plotter survival analysis tool was employed to analyze the survival of the Accepted 11 March 2021 key genes derived from the PPI network. Further analysis of the key gene expressions Published 15 April 2021 in gastric cancer and normal tissues were performed based on The Cancer Genome Corresponding author Atlas (TCGA) database and RT-qPCR verification.