Artist Sponsorships

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

ANDERTON Music Festival Capitalism

1 Music Festival Capitalism Chris Anderton Abstract: This chapter adds to a growing subfield of music festival studies by examining the business practices and cultures of the commercial outdoor sector, with a particular focus on rock, pop and dance music events. The events of this sector require substantial financial and other capital in order to be staged and achieve success, yet the market is highly volatile, with relatively few festivals managing to attain longevity. It is argued that these events must balance their commercial needs with the socio-cultural expectations of their audiences for hedonistic, carnivalesque experiences that draw on countercultural understanding of festival culture (the countercultural carnivalesque). This balancing act has come into increased focus as corporate promoters, brand sponsors and venture capitalists have sought to dominate the market in the neoliberal era of late capitalism. The chapter examines the riskiness and volatility of the sector before examining contemporary economic strategies for risk management and audience development, and critiques of these corporatizing and mainstreaming processes. Keywords: music festival; carnivalesque; counterculture; risk management; cool capitalism A popular music festival may be defined as a live event consisting of multiple musical performances, held over one or more days (Shuker, 2017, 131), though the connotations of 2 the word “festival” extend much further than this, as I will discuss below. For the purposes of this chapter, “popular music” is conceived as music that is produced by contemporary artists, has commercial appeal, and does not rely on public subsidies to exist, hence typically ranges from rock and pop through to rap and electronic dance music, but excludes most classical music and opera (Connolly and Krueger 2006, 667). -

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. August 3, 2020 to Sun. August 9, 2020

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. August 3, 2020 to Sun. August 9, 2020 Monday August 3, 2020 7:30 PM ET / 4:30 PM PT 8:00 AM ET / 5:00 AM PT Rock Legends TrunkFest with Eddie Trunk Cream - Fronted by Eric Clapton, Cream was the prototypical power trio, playing a mix of blues, Sturgis Motorycycle Rally - Eddie heads to South Dakota for the Sturgis Motorcycle Rally at the rock and psychedelia while focusing on chunky riffs and fiery guitar solos. In a mere three years, Buffalo Chip. Special guests George Thorogood and Jesse James Dupree join Eddie as he explores the band sold 15 million records, played to SRO crowds throughout the U.S. and Europe, and one of America’s largest gatherings of motorcycle enthusiasts. redefined the instrumentalist’s role in rock. 8:30 AM ET / 5:30 AM PT Premiere Rock & Roll Road Trip With Sammy Hagar 8:00 PM ET / 5:00 PM PT Mardi Gras - The “Red Rocker,” Sammy Hagar, heads to one of the biggest parties of the year, At Home and Social Mardi Gras. Join Sammy Hagar as he takes to the streets of New Orleans, checks out the Nuno Bettencourt & Friends - At Home and Social presents exclusive live performances, along world-famous floats, performs with Trombone Shorty, and hangs out with celebrity chef Emeril with intimate interviews, fun celebrity lifestyle pieces and insightful behind-the-scenes anec- Lagasse. dotes from our favorite music artists. 9:00 AM ET / 6:00 AM PT Premiere The Big Interview Special Edition 9:00 PM ET / 6:00 PM PT Keith Urban - Dan catches up with country music superstar Keith Urban on his “Ripcord” tour. -

A JBL INSTALLATION CLAIR BROTHERS And

A JBL INSTALLATION CLAIR BROTHERS and JBL Any discussion of touring sound through several design evolutions to companies will invariably bring up the incorporate the latest in transducer, name of Clair Bros. Audio, and with materials and hardware technologies. good reason. One of the pre-eminent A typical S-4 contains a pair of JBL live sound firms in the world, Clair Bros, 46 cm (18"} loudspeakers, four JBL 25 has been setting trends while taking care cm (10") loudspeakers, JBL 2441 com• of concert sound clients since 1966. pression drivers and custom-built JBL At that time, brothers Roy and Gene ultra-high frequency compression Clair began to sense a market for a port• tweeters. Each unitweighsapproximately able concert sound system to serve trav• 193 kg (425 lbs.) and measures 109 cm eling musical groups that came through (43") high by 114 cm (45") wide by 56 cm rural Pennsylvania. Starting with local (22") deep. college dates, the ambitious pair began Multiples of S-4 enclosures are used Rear view to establish a reputation for providing to assemble large arrays. A typical indoor of the concert sound that was loud and clear. scaffolding arena tour may use from 48 to 64 cabi• for the After a few years, their accounts included nets. Larger outdoor stadium and festival sound rock groups like Chicago, the Beach shows may require up to 200 or more system. Boys, Iron Butterfly, and the Grateful Dead. speaker cabinets. The company's reputation spread internationally, and English groups such as Yes, the Moody Blues and Elton John helped the company to grow. -

Steve Waksman [email protected]

Journal of the International Association for the Study of Popular Music doi:10.5429/2079-3871(2010)v1i1.9en Live Recollections: Uses of the Past in U.S. Concert Life Steve Waksman [email protected] Smith College Abstract As an institution, the concert has long been one of the central mechanisms through which a sense of musical history is constructed and conveyed to a contemporary listening audience. Examining concert programs and critical reviews, this paper will briefly survey U.S. concert life at three distinct moments: in the 1840s, when a conflict arose between virtuoso performance and an emerging classical canon; in the 1910s through 1930s, when early jazz concerts referenced the past to highlight the music’s progress over time; and in the late twentieth century, when rock festivals sought to reclaim a sense of liveness in an increasingly mediatized cultural landscape. keywords: concerts, canons, jazz, rock, virtuosity, history. 1 During the nineteenth century, a conflict arose regarding whether concert repertories should dwell more on the presentation of works from the past, or should concentrate on works of a more contemporary character. The notion that works of the past rather than the present should be the focus of concert life gained hold only gradually over the course of the nineteenth century; as it did, concerts in Europe and the U.S. assumed a more curatorial function, acting almost as a living museum of musical artifacts. While this emphasis on the musical past took hold most sharply in the sphere of “high” or classical music, it has become increasingly common in the popular sphere as well, although whether it fulfills the same function in each realm of musical life remains an open question. -

HARD Summer Music Festival Requests Move to Glen Helen Amphitheater from Auto Club Speedway

San Bernardino County Sun (http://www.sbsun.com) HARD Summer Music Festival requests move to Glen Helen Amphitheater from Auto Club Speedway By Neil Nisperos, Inland Valley Daily Bulletin Monday, July 10, 2017 San Bernardino County on Monday was still considering a request by Live Nation for the Hard Summer electronic dance music festival to be held at the Glen Helen Amphitheater this year, according to a county spokeswoman. While a press release Monday from Hard Summer organizers announced the move, the decision from the county has yet to be made, said Felisa Cardona, spokeswoman for San Bernardino County, which owns and operates the amphitheater. “They made the request to hold the Hard Summer Music Festival there last Friday, and the county is considering the request,” Cardona said. “It would be a last-minute addition to the venue.” She did not have a timeline for a decision by the county. The event was held in 2016 at Auto Club Speedway in Fontana. Speedway spokesman David Talley referred questions about the change to the Hard Summer organizers. Sources close to talks said Live Nation’s decision to move the venue might have had to do with the number of tickets sold. A representative for the event did not immediately return a request for comment. “I think these concerts go by the number of tickets they sell, the size of the business,” San Bernardino County Supervisor Curt Hagman said in a phone interview Monday. “We have several facilities throughout the region. We have several events there a year and (Glen Helen Amphitheater) would be an appropriate place for it.” All tickets purchased for the Hard Summer music festival this year will allow the ticket holder admission to the Glen Helen Amphitheater, according to organizers. -

The Clash and Mass Media Messages from the Only Band That Matters

THE CLASH AND MASS MEDIA MESSAGES FROM THE ONLY BAND THAT MATTERS Sean Xavier Ahern A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2012 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Kristen Rudisill © 2012 Sean Xavier Ahern All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor This thesis analyzes the music of the British punk rock band The Clash through the use of media imagery in popular music in an effort to inform listeners of contemporary news items. I propose to look at the punk rock band The Clash not solely as a first wave English punk rock band but rather as a “news-giving” group as presented during their interview on the Tom Snyder show in 1981. I argue that the band’s use of communication metaphors and imagery in their songs and album art helped to communicate with their audience in a way that their contemporaries were unable to. Broken down into four chapters, I look at each of the major releases by the band in chronological order as they progressed from a London punk band to a globally known popular rock act. Viewing The Clash as a “news giving” punk rock band that inundated their lyrics, music videos and live performances with communication images, The Clash used their position as a popular act to inform their audience, asking them to question their surroundings and “know your rights.” iv For Pat and Zach Ahern Go Easy, Step Lightly, Stay Free. v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis would not have been possible without the help of many, many people. -

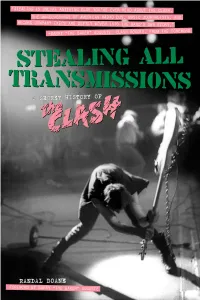

Randal Doane’S Stealing All Transmissions: a Secret History of the Clash Is Not the Story I Was Expecting from the Title

Praise “Stealing is a must-read for music fans of all varieties, for it’s much more than a book about The Clash. With a captivating narrative and well-written prose,Stealing makes sense of what happened to free-form radio and the DIY ethic of punk, and deftly connects that history to the era of file-sharing and satellite radio. Don’t miss this book. Steal it if you must!” —Michael Roberts, author of Tell Tchaikovsky the News: Rock ’n’ Roll, the Labor Question, and the Musicians’ Union, 1942–1968 “Randal Doane’s Stealing All Transmissions: A Secret History of The Clash is not the story I was expecting from the title. Thankfully. We have all read those books about artists of all stripes (and zippers), from which we learn only about misery, malfea- sance, and bad behavior. But this is not that book. The Clash is at the center of the story, but the heart of it belongs to other players. People drawn into the orbit who cared, who pushed both themselves and the band forward, who took risks because they felt and knew they were seeing and hearing a revolution. The people who were excited and inspired by the catalysts (The Clash), whose stories are integral to the core of the band’s American journey, and fascinating to finally read about, all in one place. I loved (and envied) The Clash—the gang of four who dressed better, who wore their hearts and mistakes on their zippered sleeves, and played songs with the force of racehorses bursting from the gate. -

JUDAS PRIEST BIOGRAPHY There Are Few Heavy Metal Bands That

JUDAS PRIEST BIOGRAPHY There are few heavy metal bands that have managed to scale the heights that Judas Priest have during their nearly 50-year career. Their presence and influence remains at an all-time high as evidenced by 2014's 'Redeemer of Souls' being the highest charting album of their career, a 2010 Grammy Award win for 'Best Metal Performance', being a 2006 VH1 Rock Honors recipient, a 2017 Rock and Roll Hall of Fame nomination, and they will soon release their 18th studio album, 'Firepower', through Epic Records. Judas Priest originally formed in 1969 in Birmingham, England (an area that many feel birthed heavy metal). Rob Halford, Glenn Tipton, K.K. Downing and Ian Hill would be the nucleus of musicians (along with several different drummers over the years) that would go on to change the face of heavy metal. After a 'feeling out' period of a couple of albums, 1974's 'Rocka Rolla' and 1976's 'Sad Wings of Destiny' this line-up truly hit their stride. The result was a quartet of albums that separated Priest from the rest of the hard rock pack - 1977's 'Sin After Sin', 1978's 'Stained Class' and 'Hell Bent for Leather', and 1979's 'Unleashed in the East', which spawned such metal anthems as 'Sinner', 'Diamonds and Rust', 'Hell Bent for Leather', and 'The Green Manalishi (With the Two-Pronged Crown)'. Also, Priest were one of the first metal bands to exclusively wear leather and studs – a look that began during this era and would eventually be embraced by metal heads throughout the world. -

Download the Archives Here

23.12.12 Merry Christmas Here comes the time for a family gathering. Hope your christmas tree will have ton of intersting presents for you. 22.12.12 Sting to perform in Jodhpur in march Sting is sheduled to perform in march (8, 9 or 10) for Jodhpur One World Retreat. It will be a private show for head injury victims. Only 250 couples will attend the party, with 30,000$ to 60,000$ donations. More information on jodhpuroneworld.org. 22.12.12 The last ship I made some updates to the "what we know about the play" on the forum. Please, check them to know all the informations about "The Last Ship", that could be released in 2013-2014. 16.12.12 Back to bass tour : the end The Back to bass tour has ended yesterday (well, that's what some fans hope) in Jakarta. You'll find all the tour history on the forum, and all informations about the "25 years" best of, that pointed the start of this world tour on this special page. What will follow ? We know that Sting's musical "The last ship" could be released in 2013/2014. We also know that he will perform in France and Marocco this summer. 10.12.12 Back to Bass last dates reports Follow the recent reports from the past shows from Back to Bass tour in Eastern Europe and Asia. Sting and his band met warm audiences (yesterday one in Manilla seems to have been the best from the tour according to Peter and Dominic's tweets and according to various Youtube crazy videos) You'll find pictures and videos on the forum. -

S Hewiett Sunsulannehwtt R

26 JAccid Emerg Med 1996;13:26-27 Emergency medicine at a large rock festival J Accid Emerg Med: first published as 10.1136/emj.13.1.26 on 1 January 1996. Downloaded from Susanne Hewitt, Lyn Jarrett, Bob Winter Abstract paramedic crew and 10 St John ambulances. The organisation of on-site medical per- These were distributed around the circuit. sonnel and facilities is described for an The medical centre consisted of (1) a two open air rock concert attended by 62 000 bedded resuscitation room with a full range of people. Care of the majority of patients resuscitation drugs and fluids, ECG and de- was completed on site, avoiding an fibrillator, pulse oximeter, automatic non- increased workload for local hospitals and invasive blood pressure monitor, intubation general practitioners. Many of the head and ventilation equipment; (2) two bays injuries could have been avoided by pre- with three examination couches; (3) a small venting the distribution of promotional operating theatre for minor procedures; (4) a items and large drinks containers which recovery room with two beds; (5) a reception were thrown as missiles. area for friends and relatives; (6) an office with (_JAccid Emerg Med 1996;13:26-27) a telephone. The medical centre was in radio contact with Key terms: emergency medical facilities; public events; doctors and various support services around organisation ofpersonnel. the circuit. Local hospitals were aware of the event. All contacts with persons requiring aid Open air concerts attracting large crowds were recorded on a history card and all cards remain a popular feature of the rock music were collected centrally for subsequent analysis. -

Cash Box Is Filled Are Healthy Signs

®T.M. NEWSPAPER $3.00 ^SPRING TOURING SEASON BLOSSOMS r SECOND QUARTER RELEASE SCHEDULE PACKED ' RETAIL SHELF, SALE PRICES STABLE DONNA SUMMER, POLYGRAM RESOLVE CONTRACT DISPUTE US FESTIVAL EXPANSION IN ’83 “Sparks In Outer Space” is the brilliant new aibum from the aiways original Mael brothers, featuring the first single, “Cool Places,’ a sensational duet with Jane Wiedlin of the Go-Go's and SparksT^^ Jane Wiedlin, Courtesy I.R.S. Records, Inc. On Atlantic Records and Cassettes Produced by Ron Mael and Russell Mael for Giorgio Moroder Enterprises, Ltd. 1983 AHontK Recording Corp OA Worner Commurticofiont Co BOX dSH XLIV — 44 — April 2, 1983 %HE INTERNATIONAL MUSIC / COIN MACHINE / HOME ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY VOLUME NUMBER OISHBCX EDITORML On The Mend This week’s news brings a hopeful note in the These signs could be signalling the end of the midst of what has surely been the most challenging worst . Perhaps the recession in this industry has GEORGE ALBERT period in the history of the music industry. We are bottomed out. While it is too early to tell concretely, President and Publisher still mired in the worst recession this industry has maybe the strength of the new product and the sur- MARK ALBERT to of the in- Vice President and General Manager known, but there are signs that things have begun prising potential videotaped music, turn around. creased pace of touring and the stabilizing of prices J.B. CARMICLE Vice President and General Manager, East Coast This week, the front page of Cash Box is filled are healthy signs. JIM SHARP with signs of recovery — there’s the second quarter Hopefully, the lessons that were painfully learned Vice President.