Medicinal Plant Fact Sheet: Ligusticum Porteri

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tree of Life Marula Oil in Africa

HerbalGram 79 • August – October 2008 HerbalGram 79 • August Herbs and Thyroid Disease • Rosehips for Osteoarthritis • Pelargonium for Bronchitis • Herbs of the Painted Desert The Journal of the American Botanical Council Number 79 | August – October 2008 Herbs and Thyroid Disease • Rosehips for Osteoarthritis • Pelargonium for Bronchitis • Herbs of the Painted Desert • Herbs of the Painted Bronchitis for Osteoarthritis Disease • Rosehips for • Pelargonium Thyroid Herbs and www.herbalgram.org www.herbalgram.org US/CAN $6.95 Tree of Life Marula Oil in Africa www.herbalgram.org Herb Pharm’s Botanical Education Garden PRESERVING THE FULL-SPECTRUM OF NATURE'S CHEMISTRY The Art & Science of Herbal Extraction At Herb Pharm we continue to revere and follow the centuries-old, time- proven wisdom of traditional herbal medicine, but we integrate that wisdom with the herbal sciences and technology of the 21st Century. We produce our herbal extracts in our new, FDA-audited, GMP- compliant herb processing facility which is located just two miles from our certified-organic herb farm. This assures prompt delivery of freshly-harvested herbs directly from the fields, or recently HPLC chromatograph showing dried herbs directly from the farm’s drying loft. Here we also biochemical consistency of 6 receive other organic and wildcrafted herbs from various parts of batches of St. John’s Wort extracts the USA and world. In producing our herbal extracts we use precision scientific instru- ments to analyze each herb’s many chemical compounds. However, You’ll find Herb Pharm we do not focus entirely on the herb’s so-called “active compound(s)” at fine natural products and, instead, treat each herb and its chemical compounds as an integrated whole. -

Flowering Plants Eudicots Apiales, Gentianales (Except Rubiaceae)

Edited by K. Kubitzki Volume XV Flowering Plants Eudicots Apiales, Gentianales (except Rubiaceae) Joachim W. Kadereit · Volker Bittrich (Eds.) THE FAMILIES AND GENERA OF VASCULAR PLANTS Edited by K. Kubitzki For further volumes see list at the end of the book and: http://www.springer.com/series/1306 The Families and Genera of Vascular Plants Edited by K. Kubitzki Flowering Plants Á Eudicots XV Apiales, Gentianales (except Rubiaceae) Volume Editors: Joachim W. Kadereit • Volker Bittrich With 85 Figures Editors Joachim W. Kadereit Volker Bittrich Johannes Gutenberg Campinas Universita¨t Mainz Brazil Mainz Germany Series Editor Prof. Dr. Klaus Kubitzki Universita¨t Hamburg Biozentrum Klein-Flottbek und Botanischer Garten 22609 Hamburg Germany The Families and Genera of Vascular Plants ISBN 978-3-319-93604-8 ISBN 978-3-319-93605-5 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-93605-5 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018961008 # Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature 2018 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. -

Outline of Angiosperm Phylogeny

Outline of angiosperm phylogeny: orders, families, and representative genera with emphasis on Oregon native plants Priscilla Spears December 2013 The following listing gives an introduction to the phylogenetic classification of the flowering plants that has emerged in recent decades, and which is based on nucleic acid sequences as well as morphological and developmental data. This listing emphasizes temperate families of the Northern Hemisphere and is meant as an overview with examples of Oregon native plants. It includes many exotic genera that are grown in Oregon as ornamentals plus other plants of interest worldwide. The genera that are Oregon natives are printed in a blue font. Genera that are exotics are shown in black, however genera in blue may also contain non-native species. Names separated by a slash are alternatives or else the nomenclature is in flux. When several genera have the same common name, the names are separated by commas. The order of the family names is from the linear listing of families in the APG III report. For further information, see the references on the last page. Basal Angiosperms (ANITA grade) Amborellales Amborellaceae, sole family, the earliest branch of flowering plants, a shrub native to New Caledonia – Amborella Nymphaeales Hydatellaceae – aquatics from Australasia, previously classified as a grass Cabombaceae (water shield – Brasenia, fanwort – Cabomba) Nymphaeaceae (water lilies – Nymphaea; pond lilies – Nuphar) Austrobaileyales Schisandraceae (wild sarsaparilla, star vine – Schisandra; Japanese -

National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands 1996

National List of Vascular Plant Species that Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary Indicator by Region and Subregion Scientific Name/ North North Central South Inter- National Subregion Northeast Southeast Central Plains Plains Plains Southwest mountain Northwest California Alaska Caribbean Hawaii Indicator Range Abies amabilis (Dougl. ex Loud.) Dougl. ex Forbes FACU FACU UPL UPL,FACU Abies balsamea (L.) P. Mill. FAC FACW FAC,FACW Abies concolor (Gord. & Glend.) Lindl. ex Hildebr. NI NI NI NI NI UPL UPL Abies fraseri (Pursh) Poir. FACU FACU FACU Abies grandis (Dougl. ex D. Don) Lindl. FACU-* NI FACU-* Abies lasiocarpa (Hook.) Nutt. NI NI FACU+ FACU- FACU FAC UPL UPL,FAC Abies magnifica A. Murr. NI UPL NI FACU UPL,FACU Abildgaardia ovata (Burm. f.) Kral FACW+ FAC+ FAC+,FACW+ Abutilon theophrasti Medik. UPL FACU- FACU- UPL UPL UPL UPL UPL NI NI UPL,FACU- Acacia choriophylla Benth. FAC* FAC* Acacia farnesiana (L.) Willd. FACU NI NI* NI NI FACU Acacia greggii Gray UPL UPL FACU FACU UPL,FACU Acacia macracantha Humb. & Bonpl. ex Willd. NI FAC FAC Acacia minuta ssp. minuta (M.E. Jones) Beauchamp FACU FACU Acaena exigua Gray OBL OBL Acalypha bisetosa Bertol. ex Spreng. FACW FACW Acalypha virginica L. FACU- FACU- FAC- FACU- FACU- FACU* FACU-,FAC- Acalypha virginica var. rhomboidea (Raf.) Cooperrider FACU- FAC- FACU FACU- FACU- FACU* FACU-,FAC- Acanthocereus tetragonus (L.) Humm. FAC* NI NI FAC* Acanthomintha ilicifolia (Gray) Gray FAC* FAC* Acanthus ebracteatus Vahl OBL OBL Acer circinatum Pursh FAC- FAC NI FAC-,FAC Acer glabrum Torr. FAC FAC FAC FACU FACU* FAC FACU FACU*,FAC Acer grandidentatum Nutt. -

DICOTS Aceraceae Maple Family Anacardiaceae Sumac Family

FLOWERINGPLANTS Lamiaceae Mint family (ANGIOSPERMS) Brassicaceae Mustard family Prunella vulgaris - Self Heal Cardamine nutallii - Spring Beauty Satureja douglasii – Yerba Buena Rubiaceae Madder family DICOTS Galium aparine- Cleavers Boraginaceae Borage family Malvaceae Mallow family Galium trifidum – Small Bedstraw Aceraceae Maple family Cynoglossum grande – Houndstongue Sidalcea virgata – Rose Checker Mallow Acer macrophyllum – Big leaf Maple Oleaceae Olive family MONOCOTS Anacardiaceae Sumac family Fraxinus latifolia - Oregon Ash Toxicodendron diversilobum – Poison Oak Cyperaceae Sedge family Plantaginaceae Plantain family Carex densa Apiaceae Carrot family Plantago lanceolata – Plantain Anthriscus caucalis- Bur Chervil Iridaceae Iris family Daucus carota – Wild Carrot Portulacaceae Purslane family Iris tenax – Oregon Iris Ligusticum apiifolium – Parsley-leaved Claytonia siberica – Candy Flower Lovage Claytonia perforliata – Miner’s Lettuce Juncaceae Rush family Osmorhiza berteroi–Sweet Cicely Juncus tenuis – Slender Rush Sanicula graveolens – Sierra Sanicle Cynoglossum Photo by C.Gautier Ranunculaceae Buttercup family Delphinium menziesii – Larkspur Liliaceae Lily family Asteraceae Sunflower family Caryophyllaceae Pink family Ranunculus occidentalis – Western Buttercup Allium acuminatum – Hooker’s Onion Achillea millefolium – Yarrow Stellaria media- Chickweed Ranunculus uncinatus – Small-flowered Calochortus tolmiei – Tolmie’s Mariposa Lily Adendocaulon bicolor – Pathfinder Buttercup Camassia quamash - Camas Bellis perennis – English -

Apiaceae, Apioideae) and Its Taxonomic Implications in Korea

Bangladesh J. Plant Taxon. 25(2): 175-186, 2018 (December) © 2018 Bangladesh Association of Plant Taxonomists MERICARP MORPHOLOGY OF THE TRIBE SELINEAE (APIACEAE, APIOIDEAE) AND ITS TAXONOMIC IMPLICATIONS IN KOREA 1 2 2 CHANGYOUNG LEE , JINKI KIM, ASHWINI M. DARSHETKAR , RITESH KUMAR CHOUDHARY , 3 4 5 SANG-HONG PARK , JOONGKU LEE AND SANGHO CHOI International Biological Material Research Center, Korea Research Institute of Bioscience & Biotechnology, 125 Gwahak-ro, Yuseong-gu, Daejeon 34141, South Korea Keywords: Mericarp surface characters; SEM; NMDS; UPGMA. Abstract Mericarp morphology of 24 taxa belonging to nine genera of the tribe Selineae (Family: Apiaceae) in Korea was studied by Scanning Electron Microscopy. UPGMA and NMDS analyses were performed based on 12 morphological characters. The mericarp surface characters like mericarp shape, rib number and shape, surface pattern, surface appendages and mericarp symmetry proved useful in distinguishing the genera of the tribe Selineae. Introduction The family Apiaceae comprises about 455 genera and is widely distributed across temperate regions of the world (Pimenov and Leonov, 1993). Many members of Apiaceae can be easily distinguished by umbellate inflorescence, fruits consisting of two one-seeded mericarps suspended from a split central column or carpophore and numerous minute epigynous flowers (Downie et al., 1998). Fruits of Apiaceae are known as cremocarps which in the dry state split into two mericarps. Each mericarp has a flat commissural and convex dorsal surface. Drude (1898) proposed a sound system of classification of Apiaceae with three subfamilies Hydrocotiloideae, Saniculoideae and Apioideae and 12 tribes. Apioideae is the largest subfamily consisting of 404 genera and about 2,935 species (Pimenov and Leonov, 1993) and can be distinguished from the other two subfamilies by the synapomorphies like the presence of compound umbels, well-developed vittae (secretory canals) and free carpophores. -

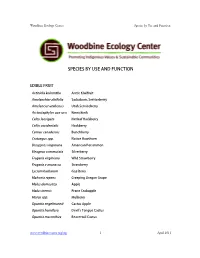

Species by Use and Function

Woodbine Ecology Center Species by Use and Function SPECIES BY USE AND FUNCTION EDIBLE FRUIT Actinidia kolomitka Arctic Kiwifruit Amelanchier alnifolia Saskatoon, Serviceberry Amelancier utahensis Utah Serviceberry Arctostaphylos uva-ursi Kinnickinik Celtis laevigata Netleaf Hackberry Celtis occidentalis Hackberry Cornus canadensis Bunchberry Crataegus spp. Native Hawthorn Diospyros virginiana American Persimmon Eleagnus commutata Silverberry Fragaria virginiana Wild Strawberry Fragaria x ananassa Strawberry Lycium barbarum Goji Berry Mahonia repens Creeping Oregon Grape Malus domesitca Apple Malus ioensis Prarie Crabapple Morus spp. Mulberry Opuntia engelmannii Cactus Apple Opuntia humifusa Devil's Tongue Cactus Opuntia macrorhiza Beavertail Cactus www.woodbinecenter.org/efg 1 April 2011 Woodbine Ecology Center Species by Use and Function Opuntia polyacantha Plains Prickly Pear Physalis heterophylla Perennial Ground Cherry Physalis longifolia Perennial Ground Cherry Physalis pruinosa Annual Groundcherry Prunus americana American Plum Prunus besseyi Sand Cherry Prunus cerasus Sour Cherry Prunus persica Peach Prunus tomentosa Nanking Cherry Prunus virginiana Chokecherry Pyrus domestica European Pear Pyrus spp. Asian Pear Ribes americanum Native Black Currant Ribes aureum Golden Currant Ribes cereum Wax Currant Ribes odoratum Clove Currant Ribes rubrum Red & White Currant Ribes uva-crispa Gooseberry Ribes x culverwellii Jostaberry Rosa spp. Wild Rose Rubus deliciosus Boulder Raspberry Rubus fruticosus Blackberry Rubus idaeus Native Red Raspberry -

Gentiana L. Spp. Gentian Gentianaceae GENTI

Plants Gentiana L. spp. Gentian Gentianaceae GENTI G. sceptrum Griseb., King’s gentian-GESC G. calycosa Griseb., Explorer’s gentian-GESA Ecology Description: Native. About 300 species, 36 in Western United States; annual or perennial herb; simple stems; fleshy roots or slender rhizomes; opposite, occasionally whorled, often clasping leaves; inflorescence compact cyme or solitary flowers, bell or funnel shaped, four or five lobed corollas, blue, violet purple, greenish, yellow, red or white; capsule, two valved, many seeded. Genti- ana sceptrum, 25-100 cm, leaves 10 to 15, 3-6 cm, blue 3-4.5 cm flowers; G. calycosa, 5-30 cm. Range and distribution: Temperate to subarctic and alpine America and Eurasia. Gentiana sceptrum: from British Columbia to California, western slope of Cas- cade Range to coast; G. calycosa: also to Rocky Moun- Gentiana calycosa G. sceptrum tains. Widespread and common for some species; others locally abundant. Biology Associations: Sitka spruce, western hemlock, Pacific Flowering and fruiting: Gentiana sceptrum blooms silver fir zones. Western redcedar, alder, willow, black from July through September, G. calycosa from July cottonwood, and bog or moist meadow. Gentiana caly- through October. cosa: mountain heather, black huckleberry, broadleaf lupine, and showy sedge. Seed: Abundant seed producer; seeds small; disperse well. Seeds are sown in autumn to early spring on top Habitat: Meadows; G. calycosa, moist open sites in of well-drained, sandy soil, watered from beneath. mountains; other gentian species including G. sceptrum, Germination in full sunlight. lower foothills and near coast. Vegetative reproduction: May be rooted from stem Successional stage: Component of well-developed, cuttings; difficult to start. -

Plant List Browder Ridge

*Non-native Browder Ridge Plant List as of 7/12/2016 compiled by Tanya Harvey T14S.R6E.S10,11 westerncascades.com FERNS & ALLIES Abies procera Ribes lacustre Athyriaceae Picea engelmannii Ribes lobbii Athyrium filix-femina Pinus contorta var. latifolia Ribes sanguineum Blechnaceae Pinus monticola Ribes viscosissimum Blechnum spicant Pseudotsuga menziesii Rhamnaceae Cystopteridaceae Tsuga heterophylla Ceanothus velutinus Cystopteris fragilis Tsuga mertensiana Rosaceae Gymnocarpium disjunctum Taxaceae Amelanchier alnifolia Dennstaedtiaceae Taxus brevifolia Holodiscus discolor Pteridium aquilinum TREES & SHRUBS: DICOTS Prunus emarginata Dryopteridaceae Adoxaceae Rosa gymnocarpa Polystichum lonchitis Sambucus racemosa Rubus lasiococcus Polystichum munitum Araliaceae Rubus leucodermis Lycopodiaceae Oplopanax horridus Rubus parviflorus Lycopodium clavatum Berberidaceae Rubus spectabilis Polypodiaceae Berberis nervosa Rubus ursinus Polypodium sp. (Mahonia nervosa) Sorbus scopulina Pteridaceae Betulaceae Sorbus sitchensis Adiantum aleuticum Alnus viridis ssp. sinuata (Adiantum pedatum var. aleuticum) (Alnus sinuata) Spiraea splendens (Spiraea densiflora) Aspidotis densa Corylus cornuta var. californica Salicaceae Cheilanthes gracillima Caprifoliaceae Salix sitchensis Symphoricarpos albus Cryptogramma acrostichoides (Cryptogramma crispa) Symphoricarpos mollis Sapindaceae (Symphoricarpos hesperius) Acer circinatum Selaginellaceae Selaginella scopulorum Celastraceae Acer glabrum var. douglasii (Selaginella densa var. scopulorum) Paxistima myrsinites -

Scots Lovage, Ligusticum Scoticum, Is Spreading in the Åland Islands, SW Finland

Memoranda Soc. Fauna Flora Fennica 85:1–5. 2009 Scots lovage, Ligusticum scoticum, is spreading in the Åland Islands, SW Finland Mikael von Numers, Carl-Adam Hæggström, Eeva Hæggström, Helene Franzén, Johan Franzén & Ralf Carlsson Mikael von Numers, Åbo Akademi University, FI-20500 Åbo, Finland Carl-Adam Hæggström, Finnish Museum of Natural History, Botanical Museum, P.O.B 7, FI-00014 University of Helsinki, Finland Eeva Hæggström, Tornfalksvägen 2 bost. 26, FI-02620 Esbo, Finland Helene & Johan Franzén, Bänö, AX-22710 Föglö, Åland, Finland Ralf Carlsson, Högbackagatan 10, AX-22100 Mariehamn, Åland, Finland Scots lovage, Ligusticum scoticum L., was probably collected already in 1892 in the Åland Islands, but it was not reported from Åland until 1970. Since then, the species has been found in an increasing number of localities. Here we report about 25 new localities found 1992–2008. There seem to be two centres for the species, one in the westernmost is- lands of Åland, between the mainland of Eckerö and the Signilskär archipelago, and the other in the northern islands of Föglö. Amore systematic investigation in the archipelagos of Åland could yield new localities. 1. Introduction However, there is a voucher specimen in H, which according to the label, was collected, on a seashore Scots lovage, Ligusticum scoticum L., was col- in Espoo at the S coast of Finland on 30 July, 1943 lected for the first time in the Åland Islands, with- (or 1948). The well-developed specimen was as- out further particulars, already on 21 July, 1892 by signed by the collector M. Puranen to Aegopodium O. -

Ligusticum Canbyi Coult. &A

The Novel Use of Metabolomics as a Hypothesis Generating Technique for Analysis of Medicinal Plants: Ligusticum canbyi Coult. & Rose and Artemisia tridentata Nutt. by Christina Turi M.Sc., University of Kent, Canterbury, UK 2009 B.Sc., University of British Columbia 2007 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE COLLEGE OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Biology) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Okanagan) June 2014 © Christina Turi, 2014 Abstract In response to the environment, plants produce a phytochemical arsenal to communicate and to withstand abiotic and biotic pressures. The average plant tissue contains upwards of 30,000 phytochemicals. The vast majority of approaches used to study plant chemistry are reductionist and only target specific classes of compounds which can be easily isolated or detected. Metabolomics is the qualitative and quantitative analysis of all metabolites present in a biological sample. By providing researchers with a phytochemical snapshot of all existing metabolites present in a sample, metabolomics has allowed researchers to study plant primary and secondary metabolism in ways that were never done before. The first objective of this thesis is to identify candidate species for studying plant neurochemicals. Statistical analysis using residual, bayesian and binomial analysis was applied to the University of Michigan’s Native American Ethnobotany Database and revealed that the genera Artemisa and Ligusticum are used most frequently during ceremony and ritual. Plant melatonin, serotonin, γ-aminobutyric acid, and acetylcholine were quantified in Artemisia tridentata Nutt. and Ligusticum canbyi Coult. & Rose. Significant variability was observed between tissue types, germplasm line and species. -

Phylogenetic Distribution and Identification of Fin-Winged Fruits

Bot. Rev. (2010) 76:1–82 DOI 10.1007/s12229-010-9041-0 Phylogenetic Distribution and Identification of Fin-winged Fruits Steven R. Manchester1,2 & Elizabeth L. O’Leary1 1 Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32611-7800, USA 2 Author for Correspondence; e-mail: [email protected] Published online: 9 March 2010 # The New York Botanical Garden 2010 Abstract Fin-winged fruits have two or more wings aligned with the longitudinal axis like the feathers of an arrow, as exemplified by Combretum, Halesia,andPtelea. Such fruits vary in dispersal mode from those in which the fruit itself is the ultimate disseminule, to schizocarps dispersing two or more mericarps, to capsules releasing multiple seeds. At least 45 families and more than 140 genera are known to possess fin-winged fruits. We present an inventory of these taxa and describe their morphological characters as an aid for the identification and phylogenetic assessment of fossil and extant genera. Such fruits are most prevalent among Eudicots, but occur occasionally in Magnoliids (Hernandiaceae: Illigera) and Monocots (Burmannia, Dioscorea, Herreria). Although convergent in general form, fin-winged fruits of different genera can be distinguished by details of the wing number, texture, shape and venation, along with characters of persistent floral parts and dehiscence mode. Families having genera with fin-winged fruits and epigynous perianth include Aizoaceae, Apiaceae, Araliaceae, Asteraceae, Begoniaceae, Burmanniaceae, Combre- taceae, Cucurbitaceae, Dioscoreaceae, Haloragaceae, Lecythidiaceae, Lophopyxida- ceae, Loranthaceae, and Styracaceae. Families with genera having fin-winged fruits and hypogynous perianth include Achariaceae, Brassicaceae, Burseraceae, Celastra- ceae, Cunoniaceae, Cyrillaceae, Fabaceae, Malvaceae, Melianthaceae, Nyctaginaceae, Pedaliaceae, Polygalaceae, Phyllanthaceae, Polygonaceae, Rhamnaceae, Salicaceae sl, Sapindaceae, Simaroubaceae, Trigoniaceae, and Zygophyllaceae.