Plants for Pollinators in Oregon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final Report

Final Report Final pre-release investigations of the gorse thrips (Sericothrips staphylinus) as a biocontrol agent for gorse (Ulex europaeus) in North America Date: August 31, 2012 Award Number: 10-CA-11420004-184 Report Period: June 1, 2010– May 31, 2012 Project Period: June 1, 2010– May 31, 2012 Recipient: Oregon State University Recipient Contact Person: Fritzi Grevstad Principal Investigator/ Project Director: Fritzi Grevstad Introduction Gorse (Ulex europaeus) is an environmental weed classified as noxious in the states of Washington, Oregon, California, and Hawaii. A classical biological control program has been applied in Hawaii with the introduction of 4 gorse-feeding arthropods, but only two of these (a mite and a seed weevil) have been introduced to the mainland U.S. The two insects that have not yet been introduced include the gorse thrips, Sericothips staphylinus (Thysanoptera: Thripidae), and the moth Agonopterix umbellana (Lepidoptera: Oecophoridae). With prior support from the U.S. Forest Service (joint venture agreement # 07-JV-281), we were able to complete host specificity testing of S. staphylinus on 44 North American plant species that were on the original test plant list. However, following review of the proposed Test Plant List, the Technical Advisory Group on Biocontrol of Weeds (TAG) recommended that we include an additional 18 plant species for testing. In this report, we present host specificity testing and related objectives necessary to bring the program to the implementation stage. Objectives (1) Acquire and grow the additional 18 species of plants recommended by the TAG. (2) Complete host specificity trials for the gorse thrips on the 18 plant species. -

The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts

The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts: The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts: A County Checklist • First Revision Melissa Dow Cullina, Bryan Connolly, Bruce Sorrie and Paul Somers Somers Bruce Sorrie and Paul Connolly, Bryan Cullina, Melissa Dow Revision • First A County Checklist Plants of Massachusetts: Vascular The A County Checklist First Revision Melissa Dow Cullina, Bryan Connolly, Bruce Sorrie and Paul Somers Massachusetts Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program The Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program (NHESP), part of the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, is one of the programs forming the Natural Heritage network. NHESP is responsible for the conservation and protection of hundreds of species that are not hunted, fished, trapped, or commercially harvested in the state. The Program's highest priority is protecting the 176 species of vertebrate and invertebrate animals and 259 species of native plants that are officially listed as Endangered, Threatened or of Special Concern in Massachusetts. Endangered species conservation in Massachusetts depends on you! A major source of funding for the protection of rare and endangered species comes from voluntary donations on state income tax forms. Contributions go to the Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Fund, which provides a portion of the operating budget for the Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program. NHESP protects rare species through biological inventory, -

Tree of Life Marula Oil in Africa

HerbalGram 79 • August – October 2008 HerbalGram 79 • August Herbs and Thyroid Disease • Rosehips for Osteoarthritis • Pelargonium for Bronchitis • Herbs of the Painted Desert The Journal of the American Botanical Council Number 79 | August – October 2008 Herbs and Thyroid Disease • Rosehips for Osteoarthritis • Pelargonium for Bronchitis • Herbs of the Painted Desert • Herbs of the Painted Bronchitis for Osteoarthritis Disease • Rosehips for • Pelargonium Thyroid Herbs and www.herbalgram.org www.herbalgram.org US/CAN $6.95 Tree of Life Marula Oil in Africa www.herbalgram.org Herb Pharm’s Botanical Education Garden PRESERVING THE FULL-SPECTRUM OF NATURE'S CHEMISTRY The Art & Science of Herbal Extraction At Herb Pharm we continue to revere and follow the centuries-old, time- proven wisdom of traditional herbal medicine, but we integrate that wisdom with the herbal sciences and technology of the 21st Century. We produce our herbal extracts in our new, FDA-audited, GMP- compliant herb processing facility which is located just two miles from our certified-organic herb farm. This assures prompt delivery of freshly-harvested herbs directly from the fields, or recently HPLC chromatograph showing dried herbs directly from the farm’s drying loft. Here we also biochemical consistency of 6 receive other organic and wildcrafted herbs from various parts of batches of St. John’s Wort extracts the USA and world. In producing our herbal extracts we use precision scientific instru- ments to analyze each herb’s many chemical compounds. However, You’ll find Herb Pharm we do not focus entirely on the herb’s so-called “active compound(s)” at fine natural products and, instead, treat each herb and its chemical compounds as an integrated whole. -

Flowering Plants Eudicots Apiales, Gentianales (Except Rubiaceae)

Edited by K. Kubitzki Volume XV Flowering Plants Eudicots Apiales, Gentianales (except Rubiaceae) Joachim W. Kadereit · Volker Bittrich (Eds.) THE FAMILIES AND GENERA OF VASCULAR PLANTS Edited by K. Kubitzki For further volumes see list at the end of the book and: http://www.springer.com/series/1306 The Families and Genera of Vascular Plants Edited by K. Kubitzki Flowering Plants Á Eudicots XV Apiales, Gentianales (except Rubiaceae) Volume Editors: Joachim W. Kadereit • Volker Bittrich With 85 Figures Editors Joachim W. Kadereit Volker Bittrich Johannes Gutenberg Campinas Universita¨t Mainz Brazil Mainz Germany Series Editor Prof. Dr. Klaus Kubitzki Universita¨t Hamburg Biozentrum Klein-Flottbek und Botanischer Garten 22609 Hamburg Germany The Families and Genera of Vascular Plants ISBN 978-3-319-93604-8 ISBN 978-3-319-93605-5 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-93605-5 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018961008 # Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature 2018 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. -

PRIORITY GRASSLANDS INITIATIVE Methodology for Identifying Priority Grasslands

PRIORITY GRASSLANDS INITIATIVE Methodology for Identifying Priority Grasslands September 2007 Building a Scientific Framework and Rationale for Sustainable Conservation and Stewardship Grasslands Conservation Council of British Columbia 954A Laval Crescent Kamloops, BC V2C 5P5 Phone: (250) 374-5787 Email: [email protected] Website: www.bcgrasslands.org Cover photo: Prickly-pear cactus by Richard Doucette Grasslands Conservation Council of British Columbia i Table of Contents Executive Summary .....................................................................................................................................i Acknowledgements .....................................................................................................................................ii Introduction.................................................................................................................................................1 Methodology Overview...............................................................................................................................2 Methodology Stages ....................................................................................................................................5 Stage 1: Initial GIS Data Gathering, Preparation and Analysis................................................................ 5 Stage 2: Expert Input .............................................................................................................................. 10 Stage 3: Assessment of Recreational -

C10 Beano2.Gen-Wis

LEGUMINOSAE PART DEUX Papilionoideae, Genista to Wisteria Revised May the 4th 2015 BEAN FAMILY 2 Pediomelum PAPILIONACEAE cont. Genista Petalostemum Glycine Pisum Glycyrrhiza Psoralea Hylodesmum Psoralidium Lathyrus Robinia Lespedeza Securigera Lotus Strophostyles Lupinus Tephrosia Medicago Thermopsis Melilotus Trifolium Onobrychis Vicia Orbexilum Wisteria Oxytropis Copyrighted Draft GENISTA Linnaeus DYER’S GREENWEED Fabaceae Genista Genis'ta (jen-IS-ta or gen-IS-ta) from a Latin name, the Plantagenet kings & queens of England took their name, planta genesta, from story of William the Conqueror, as setting sail for England, plucked a plant holding tenaciously to a rock on the shore, stuck it in his helmet as symbol to hold fast in risky undertaking; from Latin genista (genesta) -ae f, the plant broom. Alternately from Celtic gen, or French genet, a small shrub (w73). A genus of 80-90 spp of small trees, shrubs, & herbs native of Eurasia. Genista tinctoria Linnaeus 1753 DYER’S GREENWEED, aka DYER’S BROOM, WOADWAXEN, WOODWAXEN, (tinctorius -a -um tinctor'ius (tink-TORE-ee-us or tink-TO-ree-us) New Latin, of or pertaining to dyes or able to dye, used in dyes or in dyeing, from Latin tingo, tingere, tinxi, tinctus, to wet, to soak in color; to dye, & -orius, capability, functionality, or resulting action, as in tincture; alternately Latin tinctōrius used by Pliny, from tinctōrem, dyer; at times, referring to a plant that exudes some kind of stain when broken.) An escaped shrub introduced from Europe. Shrubby, from long, woody roots. The whole plant dyes yellow, & when mixed with Woad, green. Blooms August. Now, where did I put that woad? Sow at 18-22ºC (64-71ºF) for 2-4 wks, move to -4 to +4ºC (34-39ºF) for 4-6 wks, move to 5-12ºC (41- 53ºF) for germination (tchn). -

Aromatic Plants of East Asia to Enhance Natural Enemies Towards Biological Control of Insect Pests

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/331989081 Aromatic plants of East Asia to enhance natural enemies towards biological control of insect pests. A review Article in Entomologia Generalis · March 2019 DOI: 10.1127/entomologia/2019/0625 CITATIONS READS 2 242 4 authors: Séverin Hatt Qingxuan Xu Kyoto University University of Liège 35 PUBLICATIONS 231 CITATIONS 24 PUBLICATIONS 62 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Frédéric Francis Naoya Osawa University of Liège Kyoto University 427 PUBLICATIONS 4,800 CITATIONS 78 PUBLICATIONS 1,050 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Termitofuel View project Interaction between piercing-sucking insects and their host plants : focus on salivary proteome and feeding behavior View project All content following this page was uploaded by Séverin Hatt on 26 March 2019. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Aromatic plants of East Asia to enhance natural enemies towards biological control of insect pests. A review Séverin HATT1,2*, Qingxuan XU3, Frédéric FRANCIS4, Naoya OSAWA1 This paper has been published in Entomologia Generalis: https://www.schweizerbart.de/papers/entomologia/detail/38/90582/Aromatic_plants_of_East_ Asia_to_enhance_natural_enemies_towards_biological_control_of_insect_pests_A_review To cite: Hatt S., Xu Q., Francis F., Osawa N. (2019). Aromatic plants of East Asia to enhance natural enemies towards biological control of -

Outline of Angiosperm Phylogeny

Outline of angiosperm phylogeny: orders, families, and representative genera with emphasis on Oregon native plants Priscilla Spears December 2013 The following listing gives an introduction to the phylogenetic classification of the flowering plants that has emerged in recent decades, and which is based on nucleic acid sequences as well as morphological and developmental data. This listing emphasizes temperate families of the Northern Hemisphere and is meant as an overview with examples of Oregon native plants. It includes many exotic genera that are grown in Oregon as ornamentals plus other plants of interest worldwide. The genera that are Oregon natives are printed in a blue font. Genera that are exotics are shown in black, however genera in blue may also contain non-native species. Names separated by a slash are alternatives or else the nomenclature is in flux. When several genera have the same common name, the names are separated by commas. The order of the family names is from the linear listing of families in the APG III report. For further information, see the references on the last page. Basal Angiosperms (ANITA grade) Amborellales Amborellaceae, sole family, the earliest branch of flowering plants, a shrub native to New Caledonia – Amborella Nymphaeales Hydatellaceae – aquatics from Australasia, previously classified as a grass Cabombaceae (water shield – Brasenia, fanwort – Cabomba) Nymphaeaceae (water lilies – Nymphaea; pond lilies – Nuphar) Austrobaileyales Schisandraceae (wild sarsaparilla, star vine – Schisandra; Japanese -

Chromosome Numbers in Compositae, XII: Heliantheae

SMITHSONIAN CONTRIBUTIONS TO BOTANY 0 NCTMBER 52 Chromosome Numbers in Compositae, XII: Heliantheae Harold Robinson, A. Michael Powell, Robert M. King, andJames F. Weedin SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION PRESS City of Washington 1981 ABSTRACT Robinson, Harold, A. Michael Powell, Robert M. King, and James F. Weedin. Chromosome Numbers in Compositae, XII: Heliantheae. Smithsonian Contri- butions to Botany, number 52, 28 pages, 3 tables, 1981.-Chromosome reports are provided for 145 populations, including first reports for 33 species and three genera, Garcilassa, Riencourtia, and Helianthopsis. Chromosome numbers are arranged according to Robinson’s recently broadened concept of the Heliantheae, with citations for 212 of the ca. 265 genera and 32 of the 35 subtribes. Diverse elements, including the Ambrosieae, typical Heliantheae, most Helenieae, the Tegeteae, and genera such as Arnica from the Senecioneae, are seen to share a specialized cytological history involving polyploid ancestry. The authors disagree with one another regarding the point at which such polyploidy occurred and on whether subtribes lacking higher numbers, such as the Galinsoginae, share the polyploid ancestry. Numerous examples of aneuploid decrease, secondary polyploidy, and some secondary aneuploid decreases are cited. The Marshalliinae are considered remote from other subtribes and close to the Inuleae. Evidence from related tribes favors an ultimate base of X = 10 for the Heliantheae and at least the subfamily As teroideae. OFFICIALPUBLICATION DATE is handstamped in a limited number of initial copies and is recorded in the Institution’s annual report, Smithsonian Year. SERIESCOVER DESIGN: Leaf clearing from the katsura tree Cercidiphyllumjaponicum Siebold and Zuccarini. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Main entry under title: Chromosome numbers in Compositae, XII. -

Companion Planting and Insect Pest Control

Chapter 1 Companion Planting and Insect Pest Control Joyce E. Parker, William E. Snyder, George C. Hamilton and Cesar Rodriguez‐Saona Additional information is available at the end of the chapter http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/55044 1. Introduction There is growing public concern about pesticides’ non-target effects on humans and other organisms, and many pests have evolved resistance to some of the most commonly-used pesticides. Together, these factors have led to increasing interest in non-chemical, ecologically- sound ways to manage pests [1]. One pest-management alternative is the diversification of agricultural fields by establishing “polycultures” that include one or more different crop varieties or species within the same field, to more-closely match the higher species richness typical of natural systems [2, 3]. After all, destructive, explosive herbivore outbreaks typical of agricultural monocultures are rarely seen in highly-diverse unmanaged communities. There are several reasons that diverse plantings might experience fewer pest problems. First, it can be more difficult for specialized herbivores to “find” their host plant against a back‐ ground of one or more non-host species [4]. Second, diverse plantings may provide a broader base of resources for natural enemies to exploit, both in terms of non-pest prey species and resources such as pollen and nectar provided by the plant themselves, building natural enemy communities and strengthening their impacts on pests [4]. Both host-hiding and encourage‐ ment of natural enemies have the potential to depress pest populations, reducing the need for pesticide applications and increasing crop yields [5, 6]. On the other hand, crop diversification can present management and economic challenges for farmers, making these schemes difficult to implement. -

Checklist of the Vascular Plants of Redwood National Park

Humboldt State University Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University Botanical Studies Open Educational Resources and Data 9-17-2018 Checklist of the Vascular Plants of Redwood National Park James P. Smith Jr Humboldt State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/botany_jps Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Smith, James P. Jr, "Checklist of the Vascular Plants of Redwood National Park" (2018). Botanical Studies. 85. https://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/botany_jps/85 This Flora of Northwest California-Checklists of Local Sites is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Educational Resources and Data at Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Botanical Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A CHECKLIST OF THE VASCULAR PLANTS OF THE REDWOOD NATIONAL & STATE PARKS James P. Smith, Jr. Professor Emeritus of Botany Department of Biological Sciences Humboldt State Univerity Arcata, California 14 September 2018 The Redwood National and State Parks are located in Del Norte and Humboldt counties in coastal northwestern California. The national park was F E R N S established in 1968. In 1994, a cooperative agreement with the California Department of Parks and Recreation added Del Norte Coast, Prairie Creek, Athyriaceae – Lady Fern Family and Jedediah Smith Redwoods state parks to form a single administrative Athyrium filix-femina var. cyclosporum • northwestern lady fern unit. Together they comprise about 133,000 acres (540 km2), including 37 miles of coast line. Almost half of the remaining old growth redwood forests Blechnaceae – Deer Fern Family are protected in these four parks. -

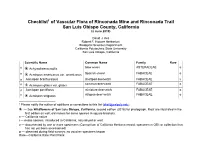

Rinconada Checklist-02Jun19

Checklist1 of Vascular Flora of Rinconada Mine and Rinconada Trail San Luis Obispo County, California (2 June 2019) David J. Keil Robert F. Hoover Herbarium Biological Sciences Department California Polytechnic State University San Luis Obispo, California Scientific Name Common Name Family Rare n ❀ Achyrachaena mollis blow wives ASTERACEAE o n ❀ Acmispon americanus var. americanus Spanish-clover FABACEAE o n Acmispon brachycarpus shortpod deervetch FABACEAE v n ❀ Acmispon glaber var. glaber common deerweed FABACEAE o n Acmispon parviflorus miniature deervetch FABACEAE o n ❀ Acmispon strigosus strigose deer-vetch FABACEAE o 1 Please notify the author of additions or corrections to this list ([email protected]). ❀ — See Wildflowers of San Luis Obispo, California, second edition (2018) for photograph. Most are illustrated in the first edition as well; old names for some species in square brackets. n — California native i — exotic species, introduced to California, naturalized or waif. v — documented by one or more specimens (Consortium of California Herbaria record; specimen in OBI; or collection that has not yet been accessioned) o — observed during field surveys; no voucher specimen known Rare—California Rare Plant Rank Scientific Name Common Name Family Rare n Acmispon wrangelianus California deervetch FABACEAE v n ❀ Acourtia microcephala sacapelote ASTERACEAE o n ❀ Adelinia grandis Pacific hound's tongue BORAGINACEAE v n ❀ Adenostoma fasciculatum var. chamise ROSACEAE o fasciculatum n Adiantum jordanii California maidenhair fern PTERIDACEAE o n Agastache urticifolia nettle-leaved horsemint LAMIACEAE v n ❀ Agoseris grandiflora var. grandiflora large-flowered mountain-dandelion ASTERACEAE v n Agoseris heterophylla var. cryptopleura annual mountain-dandelion ASTERACEAE v n Agoseris heterophylla var. heterophylla annual mountain-dandelion ASTERACEAE o i Aira caryophyllea silver hairgrass POACEAE o n Allium fimbriatum var.