Cape Wickham Golf Course Development, King Island, Tasmania

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MORNINGTON PENINSULA BIODIVERSITY: SURVEY and RESEARCH HIGHLIGHTS Design and Editing: Linda Bester, Universal Ecology Services

MORNINGTON PENINSULA BIODIVERSITY: SURVEY AND RESEARCH HIGHLIGHTS Design and editing: Linda Bester, Universal Ecology Services. General review: Sarah Caulton. Project manager: Garrique Pergl, Mornington Peninsula Shire. Photographs: Matthew Dell, Linda Bester, Malcolm Legg, Arthur Rylah Institute (ARI), Mornington Peninsula Shire, Russell Mawson, Bruce Fuhrer, Save Tootgarook Swamp, and Celine Yap. Maps: Mornington Peninsula Shire, Arthur Rylah Institute (ARI), and Practical Ecology. Further acknowledgements: This report was produced with the assistance and input of a number of ecological consultants, state agencies and Mornington Peninsula Shire community groups. The Shire is grateful to the many people that participated in the consultations and surveys informing this report. Acknowledgement of Country: The Mornington Peninsula Shire acknowledges Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders as the first Australians and recognises that they have a unique relationship with the land and water. The Shire also recognises the Mornington Peninsula is home to the Boonwurrung / Bunurong, members of the Kulin Nation, who have lived here for thousands of years and who have traditional connections and responsibilities to the land on which Council meets. Data sources - This booklet summarises the results of various biodiversity reports conducted for the Mornington Peninsula Shire: • Costen, A. and South, M. (2014) Tootgarook Wetland Ecological Character Description. Mornington Peninsula Shire. • Cook, D. (2013) Flora Survey and Weed Mapping at Tootgarook Swamp Bushland Reserve. Mornington Peninsula Shire. • Dell, M.D. and Bester L.R. (2006) Management and status of Leafy Greenhood (Pterostylis cucullata) populations within Mornington Peninsula Shire. Universal Ecology Services, Victoria. • Legg, M. (2014) Vertebrate fauna assessments of seven Mornington Peninsula Shire reserves located within Tootgarook Wetland. -

Cape Wickham Lighthouse 150 Anniversary Event Programme

Cape Wickham Lighthouse 150th Anniversary Event Programme 3 – 7 November 2011 www.kingislandlight150.com A project of King Island Tourism Inc, King Island Council & the Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA) Final Version 26 October 2011 The Story of the Lighthouse King Island‟s “Beacon of Bass Strait” is about to come-of-age! The Cape Wickham Lighthouse on the northernmost tip of King Island started service on 1st November 1861 – 150 years ago. King Island, located at the western entrance to Bass Strait, is an island rich in history with shipwrecks, lighthouses and jagged reefs. It is blessed with an abundance of long stretching sandy beaches and lush green pasture. From this little paradise are produced some of Australia's finest natural foods for which the Island is probably best known including grass fed beef, cheese, crayfish & abalone and yet there is more to this 64km long by 27km wide stretch of land than first meets the eye. The 48m tall Cape Wickham Lighthouse began operating 150 years ago on November 1st 1861 and has been in continuous operation since that first night providing - 150 years of saving lives. 150 years of guidance and direction for shipping 150 years of community capacity building 150 years of very unique history. Cape Wickham is at the northernmost tip of King Island and the 88km gap between Cape Otway (Victoria) and Cape Wickham was often a trap for the unwary Ship‟s Master seeking entry into Bass Strait. The Western entrance has become the graveyard to at least 18 ships nearing the end of their long voyages. -

Great Australian Bight BP Oil Drilling Project

Submission to Senate Inquiry: Great Australian Bight BP Oil Drilling Project: Potential Impacts on Matters of National Environmental Significance within Modelled Oil Spill Impact Areas (Summer and Winter 2A Model Scenarios) Prepared by Dr David Ellis (BSc Hons PhD; Ecologist, Environmental Consultant and Founder at Stepping Stones Ecological Services) March 27, 2016 Table of Contents Table of Contents ..................................................................................................... 2 Executive Summary ................................................................................................ 4 Summer Oil Spill Scenario Key Findings ................................................................. 5 Winter Oil Spill Scenario Key Findings ................................................................... 7 Threatened Species Conservation Status Summary ........................................... 8 International Migratory Bird Agreements ............................................................. 8 Introduction ............................................................................................................ 11 Methods .................................................................................................................... 12 Protected Matters Search Tool Database Search and Criteria for Oil-Spill Model Selection ............................................................................................................. 12 Criteria for Inclusion/Exclusion of Threatened, Migratory and Marine -

Weak but Parallel Divergence Between Ko¯Aro (Galaxias Brevipinnis) from Adjacent Lake and Stream Habitats

Evolutionary Ecology Research, 2018, 19: 29–41 Weak but parallel divergence between ko¯aro (Galaxias brevipinnis) from adjacent lake and stream habitats Travis Ingram1 and Stephanie M. Bennington2 1Department of Zoology, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand and 2Department of Marine Science, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand ABSTRACT Background: Fish in New Zealand and elsewhere in the temperate Southern Hemisphere rarely show the adaptive divergence in sympatry or parapatry seen elsewhere in the world. Hypothesis: Galaxiid fish in high-elevation lakes will show parallel morphological shifts across six lake–stream ecotones, possibly accompanied by genetic divergence. Organism: Ko¯aro, the climbing galaxias, which is often the sole fish species in New Zealand lakes that lack introduced trout. Methods: Geometric morphometric analyses of photos taken of live fish collected from lakes and streams to measure the extent and direction of body shape divergence; microsatellite genotyping to measure genetic differentiation. Results: Ko¯aro show weak or no genetic differentiation between adjacent lake and stream habitats, but do show generally parallel shifts in body shape between lakes and streams. Keywords: diadromy, Galaxias brevipinnis, parapatric speciation, phenotypic change vector analysis, phenotypic plasticity. INTRODUCTION New species frequently originate as the result of populations adapting to occupy distinct ecological niches (Schluter, 2001; Nosil, 2012). Comparisons of populations occurring across sharp habitat transitions -

Redalyc.ARE OUR ORCHIDS SAFE DOWN UNDER?

Lankesteriana International Journal on Orchidology ISSN: 1409-3871 [email protected] Universidad de Costa Rica Costa Rica BACKHOUSE, GARY N. ARE OUR ORCHIDS SAFE DOWN UNDER? A NATIONAL ASSESSMENT OF THREATENED ORCHIDS IN AUSTRALIA Lankesteriana International Journal on Orchidology, vol. 7, núm. 1-2, marzo, 2007, pp. 28- 43 Universidad de Costa Rica Cartago, Costa Rica Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=44339813005 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative LANKESTERIANA 7(1-2): 28-43. 2007. ARE OUR ORCHIDS SAFE DOWN UNDER? A NATIONAL ASSESSMENT OF THREATENED ORCHIDS IN AUSTRALIA GARY N. BACKHOUSE Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services Division, Department of Sustainability and Environment 8 Nicholson Street, East Melbourne, Victoria 3002 Australia [email protected] KEY WORDS:threatened orchids Australia conservation status Introduction Many orchid species are included in this list. This paper examines the listing process for threatened Australia has about 1700 species of orchids, com- orchids in Australia, compares regional and national prising about 1300 named species in about 190 gen- lists of threatened orchids, and provides recommen- era, plus at least 400 undescribed species (Jones dations for improving the process of listing regionally 2006, pers. comm.). About 1400 species (82%) are and nationally threatened orchids. geophytes, almost all deciduous, seasonal species, while 300 species (18%) are evergreen epiphytes Methods and/or lithophytes. At least 95% of this orchid flora is endemic to Australia. -

Bush Heritage News Autumn 2004

Bush Heritage News Autumn 2004 ABN 78 053 639 115 www.bushheritage.org In this issue Hunter Island Carnarvon three years on Memorandum of understanding Liffey interpretive walk From Outback to ocean – a new island reserve Bush Heritage Conservation Programs Manager Stuart Cowell reveals the newest Bush Heritage reserve With your help, Bush Heritage has just completed the purchase of Ethabuka Station in Australia’s Outback, protecting 214 000-ha of vital small-mammal habitat, arid-zone wetlands, grasslands and woodlands. Now, nearly 2000 km to the south, we have contracted to purchase the grazing lease on Hunter Island in Bass Strait, a 7300-ha jewel safeguarding threatened vegetation communities and bird and plant species at risk. Flying along the coastline of Hunter Island for the first time, I could hardly believe that we might be allowed the opportunity to protect this spectacular place for conservation. Its breathtaking scenery of rocky coves and white sandy beaches, wetlands, woodlands and heath surrounded by the surging power of the southern ocean, and its importance for conservation, made it seem like a jewel of inestimable value. Rocks and sand patterns on the beach at Hunter Island. Orange-bellied parrot. PHOTO: DAVE WATTS 1 LOCATION AND HISTORY Hunter Island, the largest island in the Hunter Group, lies six kilometres off the north-west tip of Tasmania.The island is 7330 ha in size, approximately 25 km long, and 6.5 km wide at its widest point.Three Hummock Island, another island in the group, is already managed for conservation. The highest point of the island lies at 90 m above sea level, from where low undulating hills roll away to the coast. -

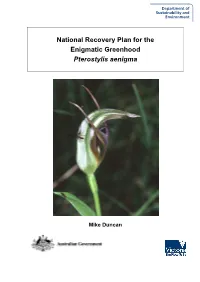

Pterostylis Aenigma

National Recovery Plan for the Enigmatic Greenhood Pterostylis aenigma Mike Duncan Prepared by Mike Duncan, Department of Sustainability and Environment, Victoria. Published by the Victorian Government Department of Sustainability and Environment (DSE) Melbourne, 2008. © State of Victoria Department of Sustainability and Environment 2008 This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Authorised by the Victorian Government, 8 Nicholson Street, East Melbourne. ISBN 978-1-74208-713-9 This is a Recovery Plan prepared under the Commonwealth Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999, with the assistance of funding provided by the Australian Government. This Recovery Plan has been developed with the involvement and cooperation of a range of stakeholders, but individual stakeholders have not necessarily committed to undertaking specific actions. The attainment of objectives and the provision of funds may be subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved. Proposed actions may be subject to modification over the life of the plan due to changes in knowledge. Disclaimer This publication may be of assistance to you but the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence that may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. An electronic version of this document is available on the Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts website www.environment.gov.au For more information contact the DSE Customer Service Centre 136 186 Citation: Duncan, M. -

Catalogue of Protozoan Parasites Recorded in Australia Peter J. O

1 CATALOGUE OF PROTOZOAN PARASITES RECORDED IN AUSTRALIA PETER J. O’DONOGHUE & ROBERT D. ADLARD O’Donoghue, P.J. & Adlard, R.D. 2000 02 29: Catalogue of protozoan parasites recorded in Australia. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum 45(1):1-164. Brisbane. ISSN 0079-8835. Published reports of protozoan species from Australian animals have been compiled into a host- parasite checklist, a parasite-host checklist and a cross-referenced bibliography. Protozoa listed include parasites, commensals and symbionts but free-living species have been excluded. Over 590 protozoan species are listed including amoebae, flagellates, ciliates and ‘sporozoa’ (the latter comprising apicomplexans, microsporans, myxozoans, haplosporidians and paramyxeans). Organisms are recorded in association with some 520 hosts including mammals, marsupials, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fish and invertebrates. Information has been abstracted from over 1,270 scientific publications predating 1999 and all records include taxonomic authorities, synonyms, common names, sites of infection within hosts and geographic locations. Protozoa, parasite checklist, host checklist, bibliography, Australia. Peter J. O’Donoghue, Department of Microbiology and Parasitology, The University of Queensland, St Lucia 4072, Australia; Robert D. Adlard, Protozoa Section, Queensland Museum, PO Box 3300, South Brisbane 4101, Australia; 31 January 2000. CONTENTS the literature for reports relevant to contemporary studies. Such problems could be avoided if all previous HOST-PARASITE CHECKLIST 5 records were consolidated into a single database. Most Mammals 5 researchers currently avail themselves of various Reptiles 21 electronic database and abstracting services but none Amphibians 26 include literature published earlier than 1985 and not all Birds 34 journal titles are covered in their databases. Fish 44 Invertebrates 54 Several catalogues of parasites in Australian PARASITE-HOST CHECKLIST 63 hosts have previously been published. -

JABG22P101 Barker

JOURNAL of the ADELAIDE BOTANIC GARDENS AN OPEN ACCESS JOURNAL FOR AUSTRALIAN SYSTEMATIC BOTANY flora.sa.gov.au/jabg Published by the STATE HERBARIUM OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA on behalf of the BOARD OF THE BOTANIC GARDENS AND STATE HERBARIUM © Board of the Botanic Gardens and State Herbarium, Adelaide, South Australia © Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources, Government of South Australia All rights reserved State Herbarium of South Australia PO Box 2732 Kent Town SA 5071 Australia © 2008 Board of the Botanic Gardens & State Herbarium, Government of South Australia J. Adelaide Bot. Gard. 22 (2008) 101 –104 © 2008 Department for Environment & Heritage, Government of South Australia NOTES & SH ORT COMMUNICATIONS New combinations in Pterostylis and Caladenia and other name changes in the Orchidaceae of South Australia R.M. Barker & R.J. Bates State Herbarium of South Australia, Plant Biodiversity Centre, P.O. Box 2732, Kent Town, South Australia 5071 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Combinations are provided in Pterostylis and Caladenia (Orchidaceae) for new species initially described in the segregate genera Arachnorchis, Bunochilus and Oligochaetochilus. Recircumscription of existing species has led to some new species being recognised for South Australia and Prasophyllum sp. West Coast (R.Tate AD96945167) is now known as Prasophyllum catenemum D.L.Jones. Introduction within Pterostylis2 R.Br. will not be adopted. Both In the past, when there have been disagreements genera in the wider sense are recognised as monophyletic between botanists about the level at which species (Hopper & Brown 2004; Jones & Clements 2002b) should be recognised, the arguments have not impinged and for the practical purpose of running Australia’s particularly on the outside community. -

CHANGES in SOUTHWESTERN TASMANIAN FIRE REGIMES SINCE the EARLY 1800S

Papers and Proceedings o/the Royal Society o/Tasmania, Volume 132, 1998 IS CHANGES IN SOUTHWESTERN TASMANIAN FIRE REGIMES SINCE THE EARLY 1800s by Jon B. Marsden-Smedley (with five tables and one text-figure) MARSDEN-SMEDLEY, ].B., 1998 (31:xii): Changes in southwestern Tasmanian fire regimes since the early 1800s. Pap.Proc. R. Soc. Tasm. 132: 15-29. ISSN 0040-4703. School of Geography and Environmental Studies, University of Tasmania, GPO Box 252-78, Hobart, Tasmania, Australia 7001. There have been major changes in the fire regime of southwestern Tasmania over the past 170 years. The fire regime has changed from an Aboriginal fire regime of frequent low-intensity fires in buttongrass moorland (mostly in spring and autumn) with only the occasional high-intensity forest fire, to the early European fire regime of frequent high-intensity fires in all vegetation types, to a regime of low to medium intensity buttongrass moorland fires and finally to the current regime of few fires. These changes in the fire regime resulted in major impacts to the region's fire-sensitive vegetation types during the early European period, while the current low fire frequency across much of southwestern Tasmania has resulted in a large proportion of the region's fire-adapted buttongrass moorland being classified as old-growth. These extensive areas of old-growth buttongrass moorland mean that the potential for another large-scale ecologically damaging wildfire is high and, to avoid this, it would be better to re-introduce a regime oflow-intensity fires into the region. Key Words: fire regimes, fire management, southwestern Tasmania, Aboriginal fire, history. -

Environmental Water Requirements for the Rubicon River

Environmental Water Requirements for The Rubicon River Tom Krasnicki Aquatic Ecologist Water Assessment and Planning Branch Water Resources Division DPIWE. Report Series WRA 02/01 May, 2002. Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS i GLOSSARY OF TERMS ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 1. INTRODUCTION 3 2. THE RUBICON RIVER 3 2.1 General Description 4 2.1.1 Catchment and Drainage System 3 2.1.2 Geomorphology and Geology 6 2.1.3 Climate and Rainfall 7 2.1.4 Vegetation 8 2.1.5 Land Use and Degradation 9 2.1.6 Port Sorell Estuary 9 2.1.7 Hydrology 11 2.2. Site Selection 13 2.2.1 The Rubicon River at Smith and Others Rd. 13 3. VALUES 15 3.1 Community Values 15 3.2 State Technical Values 17 3.3 Endangered species 18 3.4 Values Assessed 19 4. METHODOLOGY 20 4.1 Physical Habitat Data 20 4.2 Biological Data 21 4.2.1 Invertebrates 21 4.2.2 Fish 21 4.3 Hydraulic Simulation 21 4.4 Risk Analysis 22 5. RESULTS 24 5.1 Physical Habitat Data 24 5.2 Biological Data 25 5.3 Risk Analysis 26 6. DISCUSSION 29 6.1 Vertebrate Fauna 30 6.1.1 Mordacia mordax and Geotria australis 30 6.1.2 Gadopsis marmoratus 30 6.1.3 Pseudaphritis urvillii 31 6.1.4 Galaxias truttaceus and Galaxias maculatus 31 6.1.5 Galaxias brevipinnis and Neochanna cleaveri 31 6.1.6 Prototroctes maraena 32 6.1.7 Lovettia sealii and Retropinna tasmanica 32 6.1.8 Anguilla australis 32 6.1.9 Salmo trutta 32 6.1.10 Nannoperca australis and Perca fluviatilis 33 6.2 Invertebrate Fauna 33 6.2.1 Astacopsis gouldi 33 6.3 Flow Recommendations 34 6.3.1 Rubicon River at Smith and Others Rd. -

Discover a World of Family History SAVE the GSV from HISTORY!

Quarterly Journal of The Genealogical Society of Victoria Inc Getting it write Research Corner Creating a sense of tension, integrating confl ict Understanding Victoria's Legal System or struggle in a story for Genealogists VOLUME 35 ISSUE 2 JUNE 2020 $15.00 ISSN 0044-8222 Walter Hon, Beekeeper of Seventy Foot Diggings Learning from my Mistakes Henry Woodroffe: Much more than a seaman Cissie, Who Are You? Waterloo and Brexit How to: Irish Research Discover a world of family history SAVE THE GSV FROM HISTORY! For nearly 80 years the GSV has helped you find your histories, but we don’t want to be part of history! The GSV needs your help. We have lost almost all income from events and other sources for 2020 (see 'Pen of the President' in this issue). To continue with the high level of member services we need your donations. Please help us reach our target of $10,000 by the end of October. Your targeted donations to the GSV will also help stimulate our economy by multiplying its spending effect to keep our wheels turning. It is not being saved for a rainy day! You can donate via the 'Donate' button on the website, by email to [email protected], by mail using PayPal, bank transfer or cheque. All donations over $2.00 are tax deductable. Access to Records at Home Permission has been given for GSV Members to access these databases from home. For instructions on how, please email gsv@ gsv.org.au. Allow time for these instructions to be sent to you as emails are replied to on Monday to Friday, 10am to 4pm.