Baltic Loanwords in Mordvin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Võro Language in Education in Estonia

THE VÕRO LANGUAGE IN EDUCATION IN ESTONIA European Research Centre on Multilingualism and Language Learning VÕRO The Võro language in education in Estonia c/o Fryske Akademy Doelestrjitte 8 P.O. Box 54 NL-8900 AB Ljouwert/Leeuwarden The Netherlands T 0031 (0) 58 - 234 3027 W www.mercator-research.eu E [email protected] | Regional dossiers series | t ca r cum n n i- ual e : Available in this series: This document was published by the Mercator European Research Centre on Asturian; the Asturian language in education in Spain Multilingualism and Language Learning with financial support from the FryskeAkademy Basque; the Basque language in education in France (2nd) and (until 2007) the European Commission (DG: Culture and Education) and (from 2007 Basque; the Basque language in education in Spain (2nd) onwards) the Province of Fryslân and the municipality of Leeuwarden. Breton; the Breton language in education in France (2nd) Catalan; the Catalan language in education in France Catalan; the Catalan language in education in Spain Cornish; the Cornish language in education in the UK © Mercator European Research Centre on Multilingualism and Language Corsican; the Corsican language in education in France Learning, 2007 Croatian; the Croatian language in education in Austria Frisian; the Frisian language in education in the Netherlands (4th) ISSN: 1570 – 1239 Gaelic; the Gaelic language in education in the UK Galician; the Galician language in education in Spain The cover of this dossier changed with the reprint of 2008. German; the German language in education in Alsace, France (2nd) German; the German language in education in Belgium The contents of this publication may be reproduced in print, except for commercial pur- German; the German language in education in South Tyrol, Italy poses, provided that the extract is preceded by a full reference to the Mercator European Hungarian; the Hungarian language in education in Slovakia Research Centre on Multilingualism and Language Learning. -

Functioning of Political Aphorisms with a Future Meaning in the Media of the International and Russian Regional Languages

Proceedings of INTCESS 2017 4th International Conference on Education and Social Sciences 6-8 February 2017- Istanbul, Turkey FUNCTIONING OF POLITICAL APHORISMS WITH A FUTURE MEANING IN THE MEDIA OF THE INTERNATIONAL AND RUSSIAN REGIONAL LANGUAGES Flera Ya. Khabibullina1*, Iraida G. Ivanova2 & Maria N. Pirogova3 1Asst. Prof., Mari State University, Russia, [email protected] 2Asst. Prof., Mari State University, Russia, [email protected]. 3Asst. Prof., Gymnasium n° 26 André Malraux, Russia, [email protected] *Corresponding author Abstract The article is devoted to a research of problems of contact development of the international and Russian regional languages in the context of the European political discourse on the example of functioning of aphorisms with a future meaning. The expression of the category of future in aphoristic space of world and regional media of languages with different structure – French, Russian, Tatar and Mari – is studied. Special attention is paid to functioning of language / mass aphorisms for expression of the concepts "power" and "politician". The comparative description of proverbs and sayings, appeals, mottoes, slogans, clichés, symbols, quotes is carried out. The most represented aphorisms in a political discourse of the French, Russian, Tatar and Mari media are the aphorisms related to the following lexical semantic fields: foreign / domestic policy, state / country, state structures / services, institutions, parties and political movements, governing bodies, political system, authorities, heads of political structures, parties, movements and their members. Keywords: aphorism, political aphorisms, political discourse, future, power, politician, media. 1. INTRODUCTION Within the framework of functional approach, many researchers, such as M.A. Shelyakina, T.A. Sukhomlina, Y.S. -

The Vocabulary of Inanimate Nature As a Part of Turkic-Mongolian Language Commonness

ISSN 2039-2117 (online) Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences Vol 6 No 6 S2 ISSN 2039-9340 (print) MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy November 2015 The Vocabulary of Inanimate Nature as a Part of Turkic-Mongolian Language Commonness Valentin Ivanovich Rassadin Doctor of Philological Sciences, Professor, Department of the Kalmyk language and Mongolian studies Director of the Mongolian and Altaistic research Scientific centre, Kalmyk State University 358000, Republic of Kalmykia, Elista, Pushkin street, 11 Doi:10.5901/mjss.2015.v6n6s2p126 Abstract The article deals with the problem of commonness of Turkic and Mongolian languages in the area of vocabulary; a layer of vocabulary, reflecting the inanimate nature, is subject to thorough analysis. This thematic group studies the rubrics, devoted to landscape vocabulary, different soil types, water bodies, atmospheric phenomena, celestial sphere. The material, mainly from Khalkha-Mongolian and Old Written Mongolian languages is subject to the analysis; the data from Buryat and Kalmyk languages were also included, as they were presented in these languages. The Buryat material was mainly closer to the Khalkha-Mongolian one. For comparison, the material, mainly from the Old Turkic language, showing the presence of similar words, was included; it testified about the so-called Turkic-Mongolian lexical commonness. The analysis of inner forms of these revealed common lexemes in the majority of cases allowed determining their Turkic origin, proved by wide occurrence of these lexemes in Turkic languages and Turkologists' acknowledgement of their Turkic origin. The presence of great quantity of common vocabulary, which origin is determined as Turkic, testifies about repeated ancient contacts of Mongolian and Turkic languages, taking place in historical retrospective, resulting in hybridization of Mongolian vocabulary. -

On the Influence of Turkic Languages on Kalmyk Vocabulary

Asian Social Science; Vol. 11, No. 6; 2015 ISSN 1911-2017 E-ISSN 1911-2025 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education On the Influence of Turkic Languages on Kalmyk Vocabulary Valentin Ivanovich Rassadin1 & Svetlana Menkenovna Trofimova1 1 Kalmyk state University, Department of Russian language and General linguistics, Elista, Republic of Kalmykia, Russian Federation Correspondence: Valentin Ivanovich Rassadin, Kalmyk state University, Department of Russian language and General linguistics, Pushkin street, 11, Elista, 358000, Republic of Kalmykia, Russian Federation. E-mail: [email protected] Received: October 30, 2014 Accepted: December 1, 2014 Online Published: February 25, 2015 doi:10.5539/ass.v11n6p192 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ass.v11n6p192 Abstract The article covers the development and enrichment of vocabulary in the Kalmyk language and its dialects influenced by Turkic languages from ancient times when there were a hypothetical so called Altaic linguistic community in the period of general Mongolian linguistic condition and general Oirat condition. After Kalmyks moved to Volga, they already had an independent Kalmyk language. The research showed how the Kalmyk language was influenced by the ancient Turkic language, the Uigur language and the Kirghiz language, and also by the Kazakh language and the Nogai language (the Qypchaq group). Keywords: Kalmyk language vocabulary, vocabulary development, Altaic linguistic community, general Mongolian vocabulary, ancient Turkic loanwords, general Kalmyk vocabulary, Turkic loanwords in Derbet dialect, Turkic loanwords in Torgut dialect, Turkic loanwords in the Sart-Kalmyk language 1. Introduction As it is known, Turkic and Mongolian languages together with Tungus-Manchurian languages have long been considered kindred and united into one so called group of “Altaic languages”. -

Izhorians: a Disappearing Ethnic Group Indigenous to the Leningrad Region

Acta Baltico-Slavica, 43 Warszawa 2019 DOI: 10.11649/abs.2019.010 Elena Fell Tomsk Polytechnic University Tomsk [email protected] https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7606-7696 Izhorians: A disappearing ethnic group indigenous to the Leningrad region This review article presents a concise overview of selected research findings rela- ted to various issues concerning the study of Izhorians, including works by A. I. Kir′ianen, A. V. Labudin and A. A. Samodurov (Кирьянен et al., 2017); A. I. Kir′ianen, (Кирьянен, 2016); N. Kuznetsova, E. Markus and M. Muslimov (Kuznetsova, Markus, & Muslimov, 2015); M. Muslimov (Муслимов, 2005); A. P. Chush′′ialova (Чушъялова, 2010); F. I. Rozhanskiĭ and E. B. Markus (Рожанский & Маркус, 2013); and V. I. Mirenkov (Миренков, 2000). The evolution of the term Izhorians The earliest confirmed record of Izhorians (also known as Ingrians), a Finno-Ugrian ethnic group native to the Leningrad region,1 appears in thirteenth-century Russian 1 Whilst the city of Leningrad became the city of Saint Petersburg in 1991, reverting to its pre-So- viet name, the Leningrad region (also known as the Leningrad oblast) retained its Soviet name after the collapse of the USSR. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 PL License (creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/pl/), which permits redistribution, commercial and non- -commercial, provided that the article is properly cited. © The Author(s) 2019. Publisher: Institute of Slavic Studies, Polish Academy of Sciences [Wydawca: Instytut Slawistyki Polskiej Akademii Nauk] Elena Fell Izhorians: A disappearing ethnic group indigenous to the Leningrad region chronicles, where, according to Chistiakov (Чистяков, 2006), “Izhora” people were mentioned as early as 1228. -

Eastern Finno-Ugrian Cooperation and Foreign Relations

UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works Title Eastern Finno-Ugrian cooperation and foreign relations Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4gc7x938 Journal Nationalities Papers, 29(1) ISSN 0090-5992 Author Taagepera, R Publication Date 2001-04-24 DOI 10.1080/00905990120036457 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Nationalities Papers, Vol. 29, No. 1, 2001 EASTERN FINNO-UGRIAN COOPERATION AND FOREIGN RELATIONS Rein Taagepera Britons and Iranians do not wax poetic when they discover that “one, two, three” sound vaguely similar in English and Persian. Finns and Hungarians at times do. When I speak of “Finno-Ugrian cooperation,” I am referring to a linguistic label that joins peoples whose languages are so distantly related that in most world contexts it would evoke no feelings of kinship.1 Similarities in folk culture may largely boil down to worldwide commonalities in peasant cultures at comparable technological stages. The racial features of Estonians and Mari may be quite disparate. Limited mutual intelligibility occurs only within the Finnic group in the narrow sense (Finns, Karelians, Vepsians, Estonians), the Permic group (Udmurts and Komi), and the Mordvin group (Moksha and Erzia). Yet, despite this almost abstract foundation, the existence of a feeling of kinship is very real. Myths may have no basis in fact, but belief in myths does occur. Before denigrating the beliefs of indigenous and recently modernized peoples as nineteenth-century relics, the observer might ask whether the maintenance of these beliefs might serve some functional twenty-first-century purpose. The underlying rationale for the Finno-Ugrian kinship beliefs has been a shared feeling of isolation among Indo-European and Turkic populations. -

A Female Demon of Turkic Peoples

Acta Ethnographica Hungarica 64(2), 413–424 (2019) DOI: 10.1556/022.2019.64.2.11 Albasty: A Female Demon of Turkic Peoples Edina Dallos Research Fellow, MTA–ELTE–SZTE Silk Road Research Group, Hungary Abstract: Albasty is one of the most commonly known malevolent beings among Turkic peoples from the Altay Mountains via the Caucasus and up as far as the Volga River. This article focuses on Turkic data from the Volga region (Chuvash, Tartar, Bashkir) and the Eurasian Steppe (Kazak, Kyrgyz, Nogay, Uzbek). Various areas can be ascertained on the basis of verbal charms and folk-belief narratives. On the Eurasian Steppe, for example, Albasty was first and foremost a puerperal demon. In this territory, specialists (kuuču) were called in to keep away or oust the demon at birth. Many recorded legends and memorates concern healing methods and the process of becoming a healer. In contrast, epic texts or narratives are rarer,in the Volga region, yet there are certain verbal incantations against the Albasty, which here is rather a push or disease demon. Keywords: Turkic beliefs, Turkic folklore texts, Turkic demonology, folklore of Inner Asia In this paper, I will endeavour to give an overview of a mythical creature, the concept of which is widespread among most Turkic peoples. This belief has a long history and can also be evidenced in the myths and beliefs of peoples neighbouring the Turks. No other Turkic mythical beast has such extensive literature devoted to it as the Albasty. Although most relevant literature deals with the possible etymologies of the term, there are plenty of ethnographic descriptions available as well. -

The Chronicle Henry of Livonia

THE CHRONICLE of HENRY OF LIVONIA HENRICUS LETTUS TRANSLATED WITH A NEW INTRODUCTION AND NOTES BY James A. Brundage � COLUMBIA UNIVERSI'IY PRESS NEW YORK Columbia University Press RECORDS OF WESTERN CIVILIZATION is a series published under the aus Publishers Since 1893 pices of the InterdepartmentalCommittee on Medieval and Renaissance New York Chichester,West Sussex Studies of the Columbia University Graduate School. The Western Records are, in fact, a new incarnation of a venerable series, the Co Copyright© University ofWisconsin Press, 1961 lumbia Records of Civilization, which, for more than half a century, New introduction,notes, and bibliography© 2003 Columbia University Press published sources and studies concerning great literary and historical All rights reserved landmarks. Many of the volumes of that series retain value, especially for their translations into English of primary sources, and the Medieval and Renaissance Studies Committee is pleased to cooperate with Co Library of Congress Cataloging-in-PublicationData lumbia University Press in reissuing a selection of those works in pa Henricus, de Lettis, ca. II 87-ca. 12 59. perback editions, especially suited for classroom use, and in limited [Origines Livoniae sacrae et civilis. English] clothbound editions. The chronicle of Henry of Livonia / Henricus Lettus ; translatedwith a new introduction and notes by James A. Brundage. Committee for the Records of Western Civilization p. cm. - (Records of Western civilization) Originally published: Madison : University of Wisconsin Press, 1961. Caroline Walker Bynum With new introd. Joan M. Ferrante Includes bibliographical references and index. CarmelaVircillo Franklin Robert Hanning ISBN 978-0-231-12888-9 (cloth: alk. paper)---ISBN 978-0-231-12889-6 (pbk.: alk. -

Reconstructing Proto-Ugric and Proto-Uralic Object Marking Katalin É

Reconstructing Proto-Ugric and Proto-Uralic Object Marking Katalin É. Kiss ([email protected]) Research Institute for Linguistics of the Hungarian Academy and Pázmány P. University Abstract This paper demonstrates that syntactic changes in the feature specifications of functional heads can be traced back to undocumented stages of languages. It reconstructs the object–verb relation in Proto-Uralic – by means of the comparative method adapted to syntax. Present-day Uralic languages display differential object–verb agreement and/or differential accusative marking. In double-marking languages, the head licensing object–verb agreement may be different from that licensing accusative-marking. The licensing conditions of object marking are also different across languages. It is argued that the Uralic parent language had both object-verb agreement and accusative assignment licensed by a TP-external functional head with a [topic] feature. The [topic] feature of this head has been reanalyzed as [specific] in Udmurt, and as [definite] in Hungarian – via a natural extention of the content of the notion of topicality. In languages with generalized accusative assignment, i.e., in Hungarian and Tundra Nenets, the licensing of object agreement and accusative marking have been divorced; the latter has come to be associated with v. Keywords: differential object marking (DOM), object–verb agreement, accusative, syntactic reconstruction, comparative method 1. Introduction According to the Borer–Chomsky Conjecture (Borer 1984), the parametric values of grammars are expressed in the functional lexicon. Under this assumption, syntactic changes involve changes in the feature specifications of functional heads. It is an open question whether changes of this type, affecting features of morphologically real or abstract syntactic heads, can be traced back to undocumented stages of languages (cf. -

A New Classification of the Chuvash-Turkic Languages

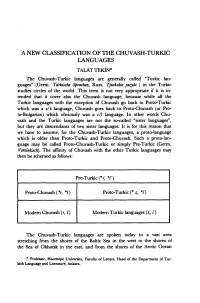

A NEW CLASSİFICATİON OF THE CHUVASH-TURKIC LANGUAGES T A L Â T TEKİN * The Chuvash-Turkic languages are generally called “Turkic lan guages” (Germ. Türkische Sprachen, Russ. Tjurkskie jazyki ) in the Turkic studies circles of the world. This term is not very appropriate if it is in- tended that it cover also the Chuvash language, because while ali the Turkic languages with the exception of Chuvash go back to Proto-Turkic vvhich was a z/s language, Chuvash goes back to Proto-Chuvash (or Pro- to-Bulgarian) vvhich obviously was a r/l language. In other vvords Chu vash and the Turkic languages are not the so-called “sister languages”, but they are descendants of two sister languages. It is for this reason that we have to assume, for the Chuvash-Turkic languages, a proto-language vvhich is older than Proto-Turkic and Proto-Chuvash. Such a proto-lan- guage may be called Proto-Chuvash-Turkic or simply Pre-Turkic (Germ. Vortürkisch). The affinity of Chuvash vvith the other Turkic languages may then be schemed as follovvs: Pre-Turkic i*r, * i ) Proto-Chuvash ( *r, */) Proto-Turkic (* z, *s) Modem Chuvash (r, l) Modem Turkic languages (z, s ) The Chuvash-Turkic languages are spoken today in a vast area stretching from the shores of the Baltic Sea in the vvest to the shores of the Sea of Okhotsk in the east, and from the shores of the Arctic Ocean * Professor, Hacettepe University, Faculty of Letters, Head of the Department of Tur- kish Language and Literatüre, Ankara. ■30 TALÂT TEKİN in the north to the shores of Persian Gulf in the south. -

Journal of Language Relationship

Российский государственный гуманитарный университет Russian State University for the Humanities Russian State University for the Humanities Institute of Linguistics of the Russian Academy of Sciences Journal of Language Relationship International Scientific Periodical Nº 3 (16) Moscow 2018 Российский государственный гуманитарный университет Институт языкознания Российской Академии наук Вопросы языкового родства Международный научный журнал № 3 (16) Москва 2018 Advisory Board: H. EICHNER (Vienna) / Chairman W. BAXTER (Ann Arbor, Michigan) V. BLAŽEK (Brno) M. GELL-MANN (Santa Fe, New Mexico) L. HYMAN (Berkeley) F. KORTLANDT (Leiden) A. LUBOTSKY (Leiden) J. P. MALLORY (Belfast) A. YU. MILITAREV (Moscow) V. F. VYDRIN (Paris) Editorial Staff: V. A. DYBO (Editor-in-Chief) G. S. STAROSTIN (Managing Editor) T. A. MIKHAILOVA (Editorial Secretary) A. V. DYBO S. V. KULLANDA M. A. MOLINA M. N. SAENKO I. S. YAKUBOVICH Founded by Kirill BABAEV © Russian State University for the Humanities, 2018 Редакционный совет: Х. АЙХНЕР (Вена) / председатель В. БЛАЖЕК (Брно) У. БЭКСТЕР (Анн Арбор) В. Ф. ВЫДРИН (Париж) М. ГЕЛЛ-МАНН (Санта-Фе) Ф. КОРТЛАНДТ (Лейден) А. ЛУБОЦКИЙ (Лейден) Дж. МЭЛЛОРИ (Белфаст) А. Ю. МИЛИТАРЕВ (Москва) Л. ХАЙМАН (Беркли) Редакционная коллегия: В. А. ДЫБО (главный редактор) Г. С. СТАРОСТИН (заместитель главного редактора) Т. А. МИХАЙЛОВА (ответственный секретарь) А. В. ДЫБО С. В. КУЛЛАНДА М. А. МОЛИНА М. Н. САЕНКО И. С. ЯКУБОВИЧ Журнал основан К. В. БАБАЕВЫМ © Российский государственный гуманитарный университет, 2018 Вопросы языкового родства: Международный научный журнал / Рос. гос. гуманитар. ун-т; Рос. акад. наук. Ин-т языкознания; под ред. В. А. Дыбо. ― М., 2018. ― № 3 (16). ― x + 78 с. Journal of Language Relationship: International Scientific Periodical / Russian State Uni- versity for the Humanities; Russian Academy of Sciences. -

Second Report Submitted by the Russian Federation Pursuant to The

ACFC/SR/II(2005)003 SECOND REPORT SUBMITTED BY THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION PURSUANT TO ARTICLE 25, PARAGRAPH 2 OF THE FRAMEWORK CONVENTION FOR THE PROTECTION OF NATIONAL MINORITIES (Received on 26 April 2005) MINISTRY OF REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION REPORT OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF PROVISIONS OF THE FRAMEWORK CONVENTION FOR THE PROTECTION OF NATIONAL MINORITIES Report of the Russian Federation on the progress of the second cycle of monitoring in accordance with Article 25 of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities MOSCOW, 2005 2 Table of contents PREAMBLE ..............................................................................................................................4 1. Introduction........................................................................................................................4 2. The legislation of the Russian Federation for the protection of national minorities rights5 3. Major lines of implementation of the law of the Russian Federation and the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities .............................................................15 3.1. National territorial subdivisions...................................................................................15 3.2 Public associations – national cultural autonomies and national public organizations17 3.3 National minorities in the system of federal government............................................18 3.4 Development of Ethnic Communities’ National