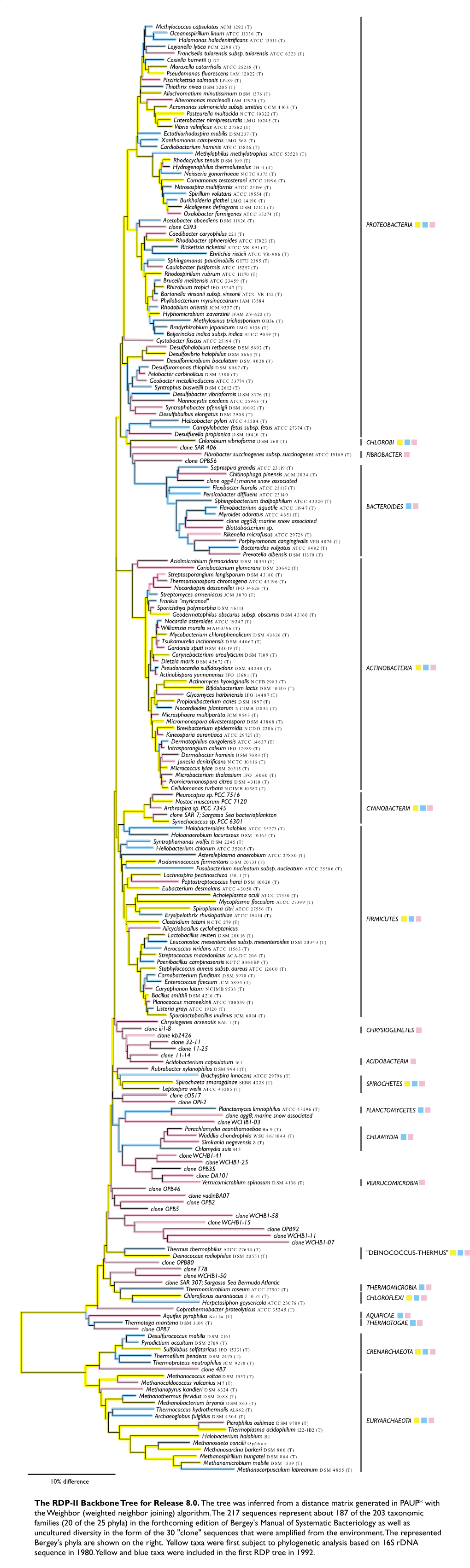

The RDP-II Backbone Tree for Release 8.0. the Tree Was Inferred from a Distance Matrix Generated in PAUP* with the Weighbor (Weighted Neighbor Joining) Algorithm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chemical Structures of Some Examples of Earlier Characterized Antibiotic and Anticancer Specialized

Supplementary figure S1: Chemical structures of some examples of earlier characterized antibiotic and anticancer specialized metabolites: (A) salinilactam, (B) lactocillin, (C) streptochlorin, (D) abyssomicin C and (E) salinosporamide K. Figure S2. Heat map representing hierarchical classification of the SMGCs detected in all the metagenomes in the dataset. Table S1: The sampling locations of each of the sites in the dataset. Sample Sample Bio-project Site depth accession accession Samples Latitude Longitude Site description (m) number in SRA number in SRA AT0050m01B1-4C1 SRS598124 PRJNA193416 Atlantis II water column 50, 200, Water column AT0200m01C1-4D1 SRS598125 21°36'19.0" 38°12'09.0 700 and above the brine N "E (ATII 50, ATII 200, 1500 pool water layers AT0700m01C1-3D1 SRS598128 ATII 700, ATII 1500) AT1500m01B1-3C1 SRS598129 ATBRUCL SRS1029632 PRJNA193416 Atlantis II brine 21°36'19.0" 38°12'09.0 1996– Brine pool water ATBRLCL1-3 SRS1029579 (ATII UCL, ATII INF, N "E 2025 layers ATII LCL) ATBRINP SRS481323 PRJNA219363 ATIID-1a SRS1120041 PRJNA299097 ATIID-1b SRS1120130 ATIID-2 SRS1120133 2168 + Sea sediments Atlantis II - sediments 21°36'19.0" 38°12'09.0 ~3.5 core underlying ATII ATIID-3 SRS1120134 (ATII SDM) N "E length brine pool ATIID-4 SRS1120135 ATIID-5 SRS1120142 ATIID-6 SRS1120143 Discovery Deep brine DDBRINP SRS481325 PRJNA219363 21°17'11.0" 38°17'14.0 2026– Brine pool water N "E 2042 layers (DD INF, DD BR) DDBRINE DD-1 SRS1120158 PRJNA299097 DD-2 SRS1120203 DD-3 SRS1120205 Discovery Deep 2180 + Sea sediments sediments 21°17'11.0" -

Annual Conference Abstracts

ANNUAL CONFERENCE 14-17 April 2014 Arena and Convention Centre, Liverpool ABSTRACTS SGM ANNUAL CONFERENCE APRIL 2014 ABSTRACTS (LI00Mo1210) – SGM Prize Medal Lecture (LI00Tu1210) – Marjory Stephenson Climate Change, Oceans, and Infectious Disease Prize Lecture Dr. Rita R. Colwell Understanding the basis of antibiotic resistance University of Maryland, College Park, MD, USA as a platform for early drug discovery During the mid-1980s, satellite sensors were developed to monitor Laura JV Piddock land and oceans for purposes of understanding climate, weather, School of Immunity & Infection and Institute of Microbiology and and vegetation distribution and seasonal variations. Subsequently Infection, University of Birmingham, UK inter-relationships of the environment and infectious diseases Antibiotic resistant bacteria are one of the greatest threats to human were investigated, both qualitatively and quantitatively, with health. Resistance can be mediated by numerous mechanisms documentation of the seasonality of diseases, notably malaria including mutations conferring changes to the genes encoding the and cholera by epidemiologists. The new research revealed a very target proteins as well as RND efflux pumps, which confer innate close interaction of the environment and many other infectious multi-drug resistance (MDR) to bacteria. The production of efflux diseases. With satellite sensors, these relationships were pumps can be increased, usually due to mutations in regulatory quantified and comparatively analyzed. More recent studies of genes, and this confers resistance to antibiotics that are often used epidemic diseases have provided models, both retrospective and to treat infections by Gram negative bacteria. RND MDR efflux prospective, for understanding and predicting disease epidemics, systems not only confer antibiotic resistance, but altered expression notably vector borne diseases. -

A Genomic Journey Through a Genus of Large DNA Viruses

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Virology Papers Virology, Nebraska Center for 2013 Towards defining the chloroviruses: a genomic journey through a genus of large DNA viruses Adrien Jeanniard Aix-Marseille Université David D. Dunigan University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] James Gurnon University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Irina V. Agarkova University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Ming Kang University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/virologypub Part of the Biological Phenomena, Cell Phenomena, and Immunity Commons, Cell and Developmental Biology Commons, Genetics and Genomics Commons, Infectious Disease Commons, Medical Immunology Commons, Medical Pathology Commons, and the Virology Commons Jeanniard, Adrien; Dunigan, David D.; Gurnon, James; Agarkova, Irina V.; Kang, Ming; Vitek, Jason; Duncan, Garry; McClung, O William; Larsen, Megan; Claverie, Jean-Michel; Van Etten, James L.; and Blanc, Guillaume, "Towards defining the chloroviruses: a genomic journey through a genus of large DNA viruses" (2013). Virology Papers. 245. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/virologypub/245 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Virology, Nebraska Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Virology Papers by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Authors Adrien Jeanniard, David D. Dunigan, James Gurnon, Irina V. Agarkova, Ming Kang, Jason Vitek, Garry Duncan, O William McClung, Megan Larsen, Jean-Michel Claverie, James L. Van Etten, and Guillaume Blanc This article is available at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/ virologypub/245 Jeanniard, Dunigan, Gurnon, Agarkova, Kang, Vitek, Duncan, McClung, Larsen, Claverie, Van Etten & Blanc in BMC Genomics (2013) 14. -

The Influence of Sodium Chloride on the Performance of Gammarus Amphipods and the Community Composition of Microbes Associated with Leaf Detritus

THE INFLUENCE OF SODIUM CHLORIDE ON THE PERFORMANCE OF GAMMARUS AMPHIPODS AND THE COMMUNITY COMPOSITION OF MICROBES ASSOCIATED WITH LEAF DETRITUS By Shelby McIlheran Leaf litter decomposition is a fundamental part of the carbon cycle and helps support aquatic food webs along with being an important assessment of the health of rivers and streams. Disruptions in this organic matter breakdown can signal problems in other parts of ecosystems. One disruption is rising chloride concentrations. Chloride concentrations are increasing in many rivers worldwide due to anthropogenic sources that can harm biota and affect ecosystem processes. Elevated chloride concentrations can lead to lethal or sublethal impacts. While many studies have shown that excessive chloride uptake impacts health (e.g. lowered respiration and growth rates) in a wide variety of aquatic organisms including microbes and benthic invertebrates). The impacts of high chloride concentrations on decomposers are less well understood. My research objective was to assess how increasing chloride concentrations affect the performance and diversity of decomposer organisms in freshwater systems. I experimentally manipulated chloride concentrations in microcosms containing leaves colonized by microbes or containing leaves, microbes and amphipods. Respiration rate, decomposition, and community composition of the microbes were measured along with the amphipod growth rate, egestion rate, and mortality. Elevated chloride concentration did not impact microbial respiration rates or leaf decomposition, but had large impacts on bacteria community composition. It did cause a decrease in instantaneous growth rate, and 100% mortality in the highest amphipod chloride treatment, but amphipod egestion rate was not significantly affected. The results of my research suggest that the widespread increases in chloride concentrations in rivers will have an impact on decomposer communities in these systems. -

Antibus Revised Thesis 11-16 For

Molecular and Cultivation-based Characterization of Ancient Algal Mats from the McMurdo Dry Valleys, Antarctica A thesis submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science by Doug Antibus December, 2009 Thesis written by Doug Antibus B.S., Kent State University, 2007 M.S., Kent State University, 2009 Approved by Dr. Christopher B. Blackwood Advisor Dr. James L. Blank Chair, Department of Biological Sciences Dr. Timothy Moerland Dean, College of Arts and Sciences iii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES………………………………………………………………………..iv LIST OF FIGURES ……………………………………………………………………...vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS…………………………………………………………......viii CHAPTER I: General Introduction……………………………………………………….1 CHAPTER II: Molecular Characterization of Ancient Algal Mats from the McMurdo Dry Valleys, Antarctica: A Legacy of Genetic Diversity Introduction……………………………………………………………....22 Results and Discussion……………………………………………..……27 Methods…………………………………………………………………..51 Literature Cited…………………………………………………………..59 CHAPTER III: Recovery of Viable Bacteria from Ancient Algal Mats from the McMurdo Dry Valleys, Antarctica Introduction………………………………………………..……………..78 Methods…………………………………………………………………..80 Results……………………………………………………………...…….88 Discussion…………………………………………………………...….106 Literature Cited………………………………………………………....109 CHAPTER IV: General Discussion…………………………………………………….120 iii LIST OF TABLES Chapter II: Molecular Characterization of Ancient Algal Mats from the McMurdo Dry Valleys, Antarctica: A Legacy of Genetic Diversity -

Inter-Domain Horizontal Gene Transfer of Nickel-Binding Superoxide Dismutase 2 Kevin M

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.12.426412; this version posted January 13, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 Inter-domain Horizontal Gene Transfer of Nickel-binding Superoxide Dismutase 2 Kevin M. Sutherland1,*, Lewis M. Ward1, Chloé-Rose Colombero1, David T. Johnston1 3 4 1Department of Earth and Planetary Science, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138 5 *Correspondence to KMS: [email protected] 6 7 Abstract 8 The ability of aerobic microorganisms to regulate internal and external concentrations of the 9 reactive oxygen species (ROS) superoxide directly influences the health and viability of cells. 10 Superoxide dismutases (SODs) are the primary regulatory enzymes that are used by 11 microorganisms to degrade superoxide. SOD is not one, but three separate, non-homologous 12 enzymes that perform the same function. Thus, the evolutionary history of genes encoding for 13 different SOD enzymes is one of convergent evolution, which reflects environmental selection 14 brought about by an oxygenated atmosphere, changes in metal availability, and opportunistic 15 horizontal gene transfer (HGT). In this study we examine the phylogenetic history of the protein 16 sequence encoding for the nickel-binding metalloform of the SOD enzyme (SodN). A comparison 17 of organismal and SodN protein phylogenetic trees reveals several instances of HGT, including 18 multiple inter-domain transfers of the sodN gene from the bacterial domain to the archaeal domain. -

Diversity and Prevalence of ANTAR Rnas Across Actinobacteria

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.11.335034; this version posted October 11, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Diversity and prevalence of ANTAR RNAs across actinobacteria Dolly Mehta1,2 and Arati Ramesh1,+ 1National Centre for Biological Sciences, Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, GKVK Campus, Bellary Road, Bangalore, India 560065. 2SASTRA University, Tirumalaisamudram, Thanjavur – 613401. +Corresponding Author: Arati Ramesh National Centre for Biological Sciences GKVK Campus, Bellary Road Bangalore, 560065 Tel. 91-80-23666930 e-mail: [email protected] Running title: Identification of ANTAR RNAs across Actinobacteria Keywords: ANTAR protein:RNA regulatory system, structured RNA, actinobacteria 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.11.335034; this version posted October 11, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. ABSTRACT Computational approaches are often used to predict regulatory RNAs in bacteria, but their success is limited to RNAs that are highly conserved across phyla, in sequence and structure. The ANTAR regulatory system consists of a family of RNAs (the ANTAR-target RNAs) that selectively recruit ANTAR proteins. This protein-RNA complex together regulates genes at the level of translation or transcriptional elongation. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Abella, C.A., X.P. Cristina, A. Martinez, I. Pibernat and X. Vila. 1998. on moderate concentrations of acetate: production of single cells. Two new motile phototrophic consortia: "Chlorochromatium lunatum" Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 35: 686-689. and "Pelochromatium selenoides". Arch. Microbiol. 169: 452-459. Ahring, B.K, P. Westermann and RA. Mah. 1991b. Hydrogen inhibition Abella, C.A and LJ. Garcia-Gil. 1992. Microbial ecology of planktonic of acetate metabolism and kinetics of hydrogen consumption by Me filamentous phototrophic bacteria in holomictic freshwater lakes. Hy thanosarcina thermophila TM-I. Arch. Microbiol. 157: 38-42. drobiologia 243-244: 79-86. Ainsworth, G.C. and P.H.A Sheath. 1962. Microbial Classification: Ap Acca, M., M. Bocchetta, E. Ceccarelli, R Creti, KO. Stetter and P. Cam pendix I. Symp. Soc. Gen. Microbiol. 12: 456-463. marano. 1994. Updating mass and composition of archaeal and bac Alam, M. and D. Oesterhelt. 1984. Morphology, function and isolation terial ribosomes. Archaeal-like features of ribosomes from the deep of halobacterial flagella. ]. Mol. Biol. 176: 459-476. branching bacterium Aquifex pyrophilus. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 16: 629- Albertano, P. and L. Kovacik. 1994. Is the genus LeptolynglYya (Cyano 637. phyte) a homogeneous taxon? Arch. Hydrobiol. Suppl. 105: 37-51. Achenbach-Richter, L., R Gupta, KO. Stetter and C.R Woese. 1987. Were Aldrich, H.C., D.B. Beimborn and P. Schönheit. 1987. Creation of arti the original eubacteria thermophiles? Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 9: 34- factual internal membranes during fixation of Methanobacterium ther 39. moautotrophicum. Can.]. Microbiol. 33: 844-849. Adams, D.G., D. Ashworth and B. -

Bacteria Associated with Vascular Wilt of Poplar

Bacteria associated with vascular wilt of poplar Hanna Kwasna ( [email protected] ) Poznan University of Life Sciences: Uniwersytet Przyrodniczy w Poznaniu https://orcid.org/0000-0001- 6135-4126 Wojciech Szewczyk Poznan University of Life Sciences: Uniwersytet Przyrodniczy w Poznaniu Marlena Baranowska Poznan University of Life Sciences: Uniwersytet Przyrodniczy w Poznaniu Jolanta Behnke-Borowczyk Poznan University of Life Sciences: Uniwersytet Przyrodniczy w Poznaniu Research Article Keywords: Bacteria, Pathogens, Plantation, Poplar hybrids, Vascular wilt Posted Date: May 27th, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-250846/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/30 Abstract In 2017, the 560-ha area of hybrid poplar plantation in northern Poland showed symptoms of tree decline. Leaves appeared smaller, turned yellow-brown, and were shed prematurely. Twigs and smaller branches died. Bark was sunken and discolored, often loosened and split. Trunks decayed from the base. Phloem and xylem showed brown necrosis. Ten per cent of trees died in 1–2 months. None of these symptoms was typical for known poplar diseases. Bacteria in soil and the necrotic base of poplar trunk were analysed with Illumina sequencing. Soil and wood were colonized by at least 615 and 249 taxa. The majority of bacteria were common to soil and wood. The most common taxa in soil were: Acidobacteria (14.757%), Actinobacteria (14.583%), Proteobacteria (36.872) with Betaproteobacteria (6.516%), Burkholderiales (6.102%), Comamonadaceae (2.786%), and Verrucomicrobia (5.307%).The most common taxa in wood were: Bacteroidetes (22.722%) including Chryseobacterium (5.074%), Flavobacteriales (10.873%), Sphingobacteriales (9.396%) with Pedobacter cryoconitis (7.306%), Proteobacteria (73.785%) with Enterobacteriales (33.247%) including Serratia (15.303%) and Sodalis (6.524%), Pseudomonadales (9.829%) including Pseudomonas (9.017%), Rhizobiales (6.826%), Sphingomonadales (5.646%), and Xanthomonadales (11.194%). -

The Micro-Ecology of Stream Biofilm Dynamics: Environmental

THE MICRO-ECOLOGY OF STREAM BIOFILM DYNAMICS: ENVIRONMENTAL DRIVERS, SUCCESSIONAL PROCESSES, AND FORENSIC APPLICATIONS Dissertation Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Biology By Jennifer M. Lang Dayton, Ohio August, 2015 THE MICRO-ECOLOGY OF STREAM BIOFILM DYNAMICS: ENVIRONMENTAL DRIVERS, SUCCESSIONAL PROCESSES, AND FORENSIC APPLICATIONS Name: Lang, Jennifer M. APPROVED BY: ___________________________________ Ryan W. McEwan, Ph.D Faculty Advisor ___________________________________ M. Eric Benbow, Ph.D Faculty Advisor __________________________________ Robert J. Kearns, Ph.D Committee Member __________________________________ Thomas M. Williams, Ph.D Committee Member __________________________________ Heather R. Jordan, Ph.D Committee Member ii ABSTRACT THE MICRO-ECOLOGY OF STREAM BIOFILM DYNAMICS: ENVIRONMENTAL DRIVERS, SUCCESSIONAL PROCESSES, AND FORENSIC APPLICATIONS Name: Lang, Jennifer M. University of Dayton Advisor: Dr. Ryan W. McEwan Microbial activity has an essential role in ecosystem processes, and in stream ecosystems, biofilms are the base of the food web that is fueled by photosynthesis and they are integral to nutrient processing. Stream biofilms are microbial communities of algae, bacteria, fungi, and protozoa encased in an extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) (molecules secreted by the microbes) that are attached to a substrate (e.g. rocks, leaves) in an aqueous environment. The substrate categorizes -

Microbial and Mineralogical Characterizations of Soils Collected from the Deep Biosphere of the Former Homestake Gold Mine, South Dakota

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln US Department of Energy Publications U.S. Department of Energy 2010 Microbial and Mineralogical Characterizations of Soils Collected from the Deep Biosphere of the Former Homestake Gold Mine, South Dakota Gurdeep Rastogi South Dakota School of Mines and Technology Shariff Osman Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory Ravi K. Kukkadapu Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, [email protected] Mark Engelhard Pacific Northwest National Laboratory Parag A. Vaishampayan California Institute of Technology See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usdoepub Part of the Bioresource and Agricultural Engineering Commons Rastogi, Gurdeep; Osman, Shariff; Kukkadapu, Ravi K.; Engelhard, Mark; Vaishampayan, Parag A.; Andersen, Gary L.; and Sani, Rajesh K., "Microbial and Mineralogical Characterizations of Soils Collected from the Deep Biosphere of the Former Homestake Gold Mine, South Dakota" (2010). US Department of Energy Publications. 170. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usdoepub/170 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Department of Energy at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in US Department of Energy Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Authors Gurdeep Rastogi, Shariff Osman, Ravi K. Kukkadapu, Mark Engelhard, Parag A. Vaishampayan, Gary L. Andersen, and Rajesh K. Sani This article is available at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/ usdoepub/170 Microb Ecol (2010) 60:539–550 DOI 10.1007/s00248-010-9657-y SOIL MICROBIOLOGY Microbial and Mineralogical Characterizations of Soils Collected from the Deep Biosphere of the Former Homestake Gold Mine, South Dakota Gurdeep Rastogi & Shariff Osman & Ravi Kukkadapu & Mark Engelhard & Parag A. -

Identify the Core Bacterial Microbiome of Hydrocarbon Degradation and A

Identify the core bacterial microbiome of hydrocarbon degradation and a shift of dominant methanogenesis pathways in oil and aqueous phases of petroleum reservoirs with different temperatures from China Zhichao Zhou1, Bo Liang2, Li-Ying Wang2, Jin-Feng Liu2, Bo-Zhong Mu2, Hojae Shim3, and Ji-Dong Gu1,* 1 Laboratory of Environmental Microbiology and Toxicology, School of Biological Sciences, The University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam Road, Hong Kong SAR, Hong Kong, People’s Republic of China 2 State Key Laboratory of Bioreactor Engineering and Institute of Applied Chemistry, East China University of Science and Technology, Shanghai 200237, People’s Republic of China 3 Faculty of Science and Technology, University of Macau, Macau, People’s Republic of China *Correspondence to: Ji-Dong Gu ([email protected]) 1 Supplementary Data 1.1 Characterization of geographic properties of sampling reservoirs Petroleum fluids samples were collected from eight sampling sites across China covering oilfields of different geological properties. The reservoir and crude oil properties together with the aqueous phase chemical concentration characteristics were listed in Table 1. P1 represents the sample collected from Zhan3-26 well located in Shengli Oilfield. Zhan3 block region in Shengli Oilfield is located in the coastal area from the Yellow River Estuary to the Bohai Sea. It is a medium-high temperature reservoir of fluvial face, made of a thin layer of crossed sand-mudstones, pebbled sandstones and fine sandstones. P2 represents the sample collected from Ba-51 well, which is located in Bayindulan reservoir layer of Erlian Basin, east Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region. It is a reservoir with highly heterogeneous layers, high crude oil viscosity and low formation fluid temperature.