Renaming Streets, Inverting Perspectives: Acts of Postcolonial Memory Citizenship in Berlin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

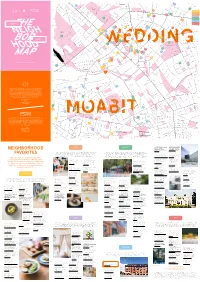

Neighborhood Favorites

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Markstraße Müllerstraße Brienzer Str. 45 Usambarastraße 73 Togostraße Soldiner Str. Schwyzer Str. Swakopmunder Str. Damarastraße Liverpooler Str. ENGLISCHES Koloniestraße 60 Gotenburger Str. Prinzenallee VIERTEL Str. Drontheimer A Dubliner Str. Biesentaler Str. A 29 Osloer Str. OSLOER STRASSE ! RESTAURANTS Armenische Str. Windhuker Str. REHBERGE Barfusstraße Glasgower Str. Stockholmer Str. 80 56 Wriezener Str. ! CAFÉS 15 93 Osloer Str. Freienwalder Str. Grüntaler Str. SCHILLERPARK 96 Petersallee 86 ! SHOPS Iranische Str. Schwedenstraße Lüderitzstraße BORNHOLMER Togostraße 63 Indische Str. Bornholmer Str. STRASSE Afrikanische Str. Edinburger Str. Str. Bellermannstraße ! ACTIVITIES Koloniestraße Koloniestraße Heinz-Galinski-Straße 25 Müllerstraße Exerzierstraße ! CULTURE Ungarnstraße Türkenstraße Klever Str. Oudenarder Str. ! BARS WEDDING Groniger Str. Seestraße Otawlstraße Sonderburger Str. B Uferstraße Spanheimstraße B 20 Gottschedstraße 23 Kongostraße 87 94 Eulerstraße 85 Gropiusstraße 97 Malplaquetstraße NAUENER PLATZ 81 Stettiner Str. Sansibarstraße Liebenwalder Str. Buttmannstraße 12 16 Thurneystraße 22 77 Grüntaler Str. VOLKSPARK Transvaalstraße Pankstraße Togostraße Turiner Str. 91 REHBERGE Lüderitzstraße SEESTRASSE 53 Bornemannstraße Bastienstraße Hochstädter Str. Schulstraße Zingster Str. Schönstedtstraße Heidebrinker Str. 1 95 Böttgerstraße Behmstraße Guineastraße 32 68 Amsterdamer Str. 13 Maxstraße Müllerstraße 2 GESUNDBRUNNEN 59 Utrechter Str. 37 MOABIT Kameruner Str. Prinz-Eugen-Straße Sambesistraße 99 Schererstraße Wiesenstraße Genter Str. 61 58 Antwerpener Str. Kösliner Str. Adolfstraße 6 Senegalstraße Dualastraße 76 41 Reinickendorfer Str. 54 Ramierstraße Lütticher Str. 51 Ugandastraße Nazarethkirchstraße C C Hochstraße C HUMBOLDTHAIN LEOPOLDPLATZ Tangastraße Seestraße 82 Brüsseler Str. Ruheplatzstraße Wiesenstraße Amrumer Str. 14 65 Graunstraße Pankstraße Antonstraße 90 Swinemünder Str. Dohnagestell Ostender Str. 83 30 Pasewalker Str. Pasewalker Str. HUMBOLDTHAIN Putbusser Str. Genter Str. 8 55 89 98 Rügener Str. -

Class Action Complaint

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK _____________________________________________x VEKUII RUKORO, Paramount Chief of the Ovaherero People and Representative of the Ovaherero Traditional Authority; DAVID FREDERICK, Chief and Chairman of the Nama Traditional Authorities Association, Civ. No. 17-0062 THE ASSOCIATION OF THE OVAHERERO GENOCIDE IN THE USA INC.; and BARNABAS VERAA KATUUO, CLASS ACTION Individually and as an Officer of The Association of the COMPLAINT Ovaherero Genocide in the USA, Inc., on behalf of themselves and all other Ovaherero and Nama indigenous peoples, Plaintiffs, Jury Trial Demanded -against- FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF GERMANY, Defendant. _____________________________________________x Plaintiffs, by and through their attorneys, McCallion & Associates LLP, bring this Class Action Complaint against Defendant Federal Republic of Germany as follows: SUMMARY OF THE COMPLAINT 1. Plaintiffs bring this action on behalf of all the Ovaherero and Nama peoples for damages resulting from the horrific genocide and unlawful taking of property in violation of international law by the German colonial authorities during the 1885 to 1909 period in what was formerly known as South West Africa, and is now Namibia. Plaintiffs also bring this action to, among other things, enjoin and restrain the Federal Republic of Germany from continuing to exclude plaintiffs and other lawful representatives of the Ovaherero and Nama people from participation in discussions and negotiations regarding the subject matter of this Complaint, in violation of plaintiffs’ rights under international law, including the U.N. Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People to self-determination for all indigenous peoples and their right to participate and speak for themselves regarding all matters relating to the losses that they have suffered. -

Case 1:17-Cv-00062 Document 1 Filed 01/05/17 Page 1 of 22

Case 1:17-cv-00062 Document 1 Filed 01/05/17 Page 1 of 22 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK _____________________________________________x VEKUII RUKORO, Paramount Chief of the Ovaherero People and Representative of the Ovaherero Traditional Authority; DAVID FREDERICK, Chief and Chairman of the Nama Traditional Authorities Association, Civ. No. THE ASSOCIATION OF THE OVAHERERO GENOCIDE IN THE USA INC.; and BARNABAS VERAA KATUUO, CLASS ACTION Individually and as an Officer of The Association of the COMPLAINT Ovaherero Genocide in the USA, Inc., on behalf of themselves and all other Ovaherero and Nama indigenous peoples, Plaintiffs, Jury Trial Demanded -against- FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF GERMANY, Defendant. _____________________________________________x Plaintiffs, by and through their attorneys, McCallion & Associates LLP, bring this Class Action Complaint against Defendant Federal Republic of Germany as follows: SUMMARY OF THE COMPLAINT 1. Plaintiffs bring this action on behalf of all the Ovaherero and Nama peoples for damages resulting from the horrific genocide and unlawful taking of property in violation of international law by the German colonial authorities during the 1885 to 1909 period in what was formerly known as South West Africa, and is now Namibia. Plaintiffs also bring this action to, among other things, enjoin and restrain the Federal Republic of Germany from continuing to exclude plaintiffs and other lawful representatives of the Ovaherero and Nama people from participation in discussions and negotiations regarding the subject matter of this Complaint, in Case 1:17-cv-00062 Document 1 Filed 01/05/17 Page 2 of 22 violation of plaintiffs’ rights under international law, including the U.N. -

Bezirksamt-Mitte.Pdf

] BEZIRKSAWIT IMiTTE be i / VON BERLIN Regionaldienstleitung Regionaler Sozialpädagogischer Dienst It Kerstin Kubisch-Piesk | Jug R 3 Tel. 030/9018-45340 | R. 307 Der Regionale Sozialpädagogische Dienst (RSD) steht Kin- [email protected] dem. Jugendlichen, Eltern und Familien bei Problemen oder Konflikten mit Beratung, Vermittlung und Informa- Geschäftszimmer tionen zur Seite und entwickelt mit ihnen gemeinsam Lö- Daniela Beig | Jug R 301 sungen. Zur Unterstützung bietet der RSD auch individu- Tel. 030/9018-45310 | R. 302 eile Erziehungshilfen an. Bezirksamt Mitte [email protected] Wenn Sie das erste Mal mit uns in Kontakt treten, dann von Berlin erreichen Sie uns über den Tagesdienst vor Ort: Jugendanit Regionale Jugend- und Familienförderung Wann? Di 9-12 Uhr, Do 16-18 Uhr Regionaldienst Wo? Region Gesundbrunnen Selbstbewusstsein, Selbständigkeit und soziales Mitein- Grüntaler Straße 21, 2. OG /4. OG Gesundbrunnen ander fördern und zum Mitgestalten in der Gesellschaft 13357 Berlin anregen, das sind Kernziele der Jugendarbeit. InJugend- Unterstützung, die ankommt. einrichtungen können Jugendliche ihre Talente entfal- oder telefonisch zu folgenden Zeiten: ten, Neues ausprobieren und persönliche Probleme mit professionellen Ansprechpartner*innen besprechen. Wann? Mo, Di., Mi 9-15 Uhr, Do 12-18 Uhr, Fr 9-14 Uhr Familien werden durch Angebote der Familienförderung Wie? Tel. 030/9018-45355 bei der Bewältigung von Erziehungs- und Bildungsauf- Fax030/9018-45331 gaben unterstützt. Dadurch wird die aktive Beteiligung von Familien, Kindern und Jugendlichen am gesellschaft- Für alle weiteren Anliegen sind wir nach vorheriger lichen Leben gefördert. Terminvereinbarung gerne für Sie da. Sozialraumkoordinator Osloer Straße Weitere Informationen erhalten Sie auch unter: Peter Barton | Jug R 3401 www.berlin.de/ba-mitte Tel. -

Mitte Friedrichstr. 96, 10117 Berlin, Germany Tel.: (+49) 30 20 62 660

HOW TO GET THERE? WHERE TO FIND NH COLLECTION BERLIN MITTE FRIEDRICHSTRASSE? Area: Mitte Friedrichstr. 96, 10117 Berlin, Germany Tel.: (+49) 30 20 62 660 FROM THE AIRPORT - From Tegel Airport: Take the bus TXL, which runs every 20 minutes, to get to the "Unter den Linden/Friedrichstraße". From there, walk to the S-Bahn station “Friedrichstraße” - the hotel is on the right site. It is a 35 minute trip. Taxi: The 20-25 minute cab ride costs about €25. - From Schönefeld Airport: Take the train S9 to Spandau. It runs every 20 minutes. Exit at "Friedrichstraße" station. You will find the hotel on the right side, next to the station. It is a 40 minute trip. Taxi: The 30-40 minute cab ride costs about €55. FROM THE TRAIN STATION From Berlin Central Station (Hauptbahnhof): Take one of the regional trains (S3, S5, S7, S9 or RB14). Exit at “Friedrichstrasse” station. You will find the hotel on the right side, next to the station. It is a 5 minute trip. Taxi: The 10 minute cab ride costs about €10. Please note: For public transportation in zones A, B, and C, choose between a single ticket (3,40€), a day ticket (7,70€) or a ticket for one week (37,50€). You can take the train and the bus in all sectors (ABC). For public transportation in zones A and B exclusively: choose between a single ticket (2,80€), a day ticket (7,00€) or a ticket for a week (30,00€). You can take the train and the bus in sector A and B. -

Stadtteilarbeit Im Bezirk Mitte

Stadtteilarbeit im Bezirk Mitte In unseren Nachbarschaftstreffpunkten finden Sie viele ver- Stadtteilzentrum schiedene Angebote für Jung und Alt. Hier treffen sich Nach- barinnen und Nachbarn in Kursen oder Gruppen, zu kultu- Selbsthilfe Kontaktstelle rellen Veranstaltungen, um ihre Ideen für die Nachbarschaft Nachbarschaftstreff umzusetzen, um sich beraten zu lassen oder um Räume für Familienzentrum eigene Projekte und Festivitäten anzumieten. Mehrgenerationenhaus Osloer mit Rollstuhl zugänglich Alexanderplatz Straße WC rollstuhlgerechtes WC 19 1 Begegnungsstätte Die unterschiedlichen Spandauer Straße 21 Begrifflichkeiten der Bezirksamt Mitte von Berlin 18 Nachbarschaftseinrichtungen Spandauer Str. 2 | 10178 Berlin Parkviertel liegen an den jeweiligen Tel. 242 55 66 Förderprogrammen. 22 25 17 www.berlin.de/ba-mitte WC 20 2 Kieztreff Koepjohann Wedding Koepjohann’sche Stiftung Zentrum Große Hamburger Str. 29 10115 Berlin | Tel. 30 34 53 04 4 www.koepjohann.de WC Brunnenstraße Nord 3 KREATIVHAUS Stadtteilkoordination 26 5 8 KREATIVHAUS e.V. | Fischerinsel 3 | 10179 Berlin 7 6 Tel. 238 09 13 | www.kreativhaus-tpz.de WC Brunnenstraße Nord Moabit West 10 4 Begegnungsstätte im Kiez Brunnenstraße Jahresringe Gesellschaft für Arbeit | 15 Süd und Bildung e.V. Stralsunder Str. 6 16 13355 Berlin | Tel. 464 50 36 13 www.jahresringe-ev.de/ Moabit Ost 9 begegnungsstatten.html WC 14 2 5 Begegnungsstätte Haus Bottrop 12 Alexanderplatz Selbst-Hilfe im Vor-Ruhestand e.V. Schönwalder Str. 4 | 13347 Berlin Tel. 493 36 77 | www.sh-vor-ruhestand.de WC 1 6 Familienzentrum Wattstraße Pfefferwerk Stadtkultur gGmbH | Wattstr. 16 11 | | 13355 Berlin Tel. 32 51 36 55 www.pfefferwerk.de Regierungs- WC viertel 3 7 Kiezzentrum Humboldthain Tiergarten Süd DRK-Kreisverband Wedding / Prenzlauer Berg e. -

German Bundestag Motion

German Bundestag Printed paper 18/5407 18th Electoral Term Date 01 July 2015 Motion submitted by Members of the Bundestag Niema Movassat, Wolfgang Gehrcke, Jan van Aken, Christine Buchholz, Sevim Daǧdelen, Dr. Diether Dehm, Annette Groth, Heike Hänsel, Inge Höger, Andrej Hunko, Ulla Jelpke, Katrin Kunert, Stefan Liebich, Dr. Alexander S. Neu, Alexander Ulrich, Dr. Sahra Wagenknecht and The LEFT PARTY parliamentary group Reconciliation with Namibia – remembrance and apology for the genocide in the former colony of German South-West Africa The German Bundestag is requested to adopt the following motion: I. The German Bundestag notes: 1. The German Bundestag remembers the atrocities perpetrated by the colonial troops of the German Empire in the former colony of German South-West Africa, and commemorates the victims of massacres, expulsions, expropriation, forced labour, rape, medical experiments, deportations and inhuman confinement in concentration camps. The war of extermination waged by German colonial troops in the years 1904 to 1908 resulted in the death of up to 80 percent of the Herero people, more than half of the Nama people, and a large part of the Damara and San ethnic groups. 2. The German Bundestag acknowledges the heavy burden of guilt that the German colonial troops incurred by carrying out these crimes against the Herero, Nama, Damara and San peoples. These war crimes, expulsions and massacres committed by the German Empire were genocide. The orders issued by Lieutenant General Lothar von Trotha on 2 October 1904 against the Herero and on 22 April 1905 against the Nama, along with the actual warfare that ensued, are clear evidence of the exterminatory intent towards these ethnic groups, which later also claimed the lives of Damara and San people. -

Altes Krankenhaus Staaken: the Metropolitan Park Information in Leichter Sprache

Altes Krankenhaus Staaken: The Metropolitan Park Information in Leichter Sprache Das Gelände des ehemaligen Krankenhaus Staaken liegt ganz im Westen des Bezirks Spandau. Es hat sich in den letzten 100 Jahren mehrmals stark verändert. Das Gelände und die Gebäude wurden über 20 Jahre nicht genutzt und sind stark verfallen und beschädigt. Jetzt sollen die Gebäude als Wohnungen umgebaut werden zum sogenannten »Metropolitan Park«. Was war auf dem Gelände früher? Im Jahr 1915 kaufte die Firma Luftschiffbau Zeppelin AG das Gelände. Das war vor über 100 Jahren. Die Firma baute hier Zeppeline und der Fabrik-Standort Staaken wurde für kurze Zeit weltberühmt. Mitte der 1920er Jahre gehörte das Gelände dann der Deutschen Lufthansa AG. Hier war damals der modernste Standort in Deutschland zur Wartung und Reparatur von Flugzeugen. Ab Mitte der 1930er Jahre wurde das Gelände militärisch genutzt und zu einem Standort der Luftwaffe der Wehrmacht umgebaut. Dazu gehörte auch der Neubau von Kasernen für Soldaten und andere Beschäftigte. Im 2. Welt-Krieg wurde das Gelände von Bomben zerstört, aber die Gebäude bekamen nur geringe Beschädigungen. 1 Nach dem 2. Welt-Krieg nutzte die Finanz-Hochschule der DDR das Gelände. Ab dem Jahr 1958 war dort dann eine Außenstelle vom Kreis-Krankenhaus Nauen. Dafür musste damals viel umgebaut werden. Das Krankenhaus nutzte das Gelände, bis es im Jahr 1998 schließen musste. Was ist jetzt auf dem Gelände geplant? Die Prinz von Preussen Grundbesitz AG hat das Gelände im Jahr 2016 gekauft, um dort Wohnungen zu bauen. Insgesamt soll es über 400 Wohnungen geben. Ungefähr die Hälfte davon wird in umgebauten Gebäuden vom ehemaligen Krankenhaus Staaken sein. -

Informationen Des Bezirksamtes Mitte Von Berlin Für Geflüchtete Menschen – Stand 04 / 2016

InformationenInformationen des des BezirksamtesBezirksamtes MitteMitte vonvon BerlinBerlin für geflüchtetefür geflüchtete Menschen Menschen Informationen des Bezirksamtes Mitte von Berlin für geflüchtete Menschen – Stand 04 / 2016 - Inhaltsverzeichnis Ansprechperson Gesamtkoordination Flüchtlingsfragen S. 1 Gesundheit Ansprechperson Koordination S. 2 Beratungsstelle für behinderte und krebskranke Menschen S. 3 Beratungsstelle für kindliche Entwicklungsförderung S. 4 Beratungsstelle für sehbehinderte Menschen S. 5 Hygiene und Umweltmedizin S. 6 Kinder- und Jugendgesundheitsdienst (KJGD) S. 7 Kinder- und Jugendpsychiatrischer Dienst (KJPD) S. 9 Sozialpsychiatrischer Dienst S. 10 Zahnärztlicher Dienst S. 12 Zentrum für Familienplanung und Schwangerschaft S. 13 Zentrum für sexuelle Gesundheit S. 15 Externe Anlaufstellen medizinische Versorgung S. 16 Kinder und Jugend Erziehungs- und Familienberatung S. 18 Kindertagesbetreuung S. 20 Regionaler Sozialpädagogischer Dienst, Kindernotdienst, Ansprechpersonen S. 22 Schule Einschulung in die Grundschule S. 25 Einschulung in die Oberschule S. 27 Deutschkurse S. 29 Bürgerdienste Ansprechperson Koordination S. 31 Ansprechperson Back Office S. 32 Bürgerämter S. 33 Standesamt S. 35 Wohnraumvermittlung S. 36 Bibliotheken Stadtbiliothek Mitte S. 38 Anlagen Beratungsstellen (Aufenthaltsrecht, Asylrecht, Sozialleistungen) Bibliotheken berlinweit Integrationslotsen Integrationsbüro Mitte Koordination flüchtlingsrelevanter Fragen im Bezirksamt Mitte Ansprechperson: Frau Majer (030) 9018 - 33749 (030) 9018 -

Mitte Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg Pankow

► Vorwort 5 Mitte 1 Das »himmelbeet« in Wedding 6 2 Einkäufen im Mini-Kaufhaus in Wedding 8 3 Smart Eating in der Data Kitchen 10 4 Bibliothek am Luisenbad 12 5 Gleim-Oase: die grüne Insel im Wedding 14 6 Leckere Burger in ausgefallener Location 16 7 Franzose mit witzigem Menü-Konzept 18 8 Cocktail trinken in einer versteckten Bar 20 9 Katz Orange: Restaurant in alter Brauerei 22 10 Staunen in der Wunderkammer Olbricht 24 11 Die Dachterrasse des Hotel AMANO 26 12 Brötchen holen in Sarah Wieners Bio-Bäckerei 26 13 Cowshed Spa im Soho House 28 14 Tadshikische Teestube: märchenhaft Tee genießen 30 15 Kennedy Museum: in der Jüdischen Mädchenschule 32 16 Beeindruckende Boros Collection 34 17 Entspannen über den Dächern der Stadt 36 18 Alter Grenzturm am Potsdamer Platz 36 19 Ein Tag Luxus, bitte! 38 Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg 20 Sonnenuntergang auf der Modersohnbrücke 40 21 Das beliebteste Outlet der Stadt 42 22 Minigolf bei Schwarzlicht 44 23 Street Food Thursday 46 24 Panoramablick über Kreuzberg 46 25 Akupunktur, die sich jeder leisten kann 47 26 Ein Besuch im Pfefferhaus 48 27 Die kleinste Disko der Welt 50 28 Crazy Hot Dogs 50 29 Kalifornien zum Schlecken 52 Pankow 30 Erinnerungen in der Alten Bäckerei Pankow 54 31 Die Ruine des Kinderkrankenhauses in Weißensee 56 32 Lustige Tischtennis-Bar im Prenzlauer Berg 56 33 Türkische Küche - modern interpretiert 58 34 Stulle essen bei Suicide Sue 60 35 Onkel Philipp's Spielzeugwerkstatt 62 36 Verwunschene Oase auf dem Friedhof 64 37 Zur Ruhe kommen im Stadtkloster Segen 66 38 Entspannen im Ruhepool -

The Visual Archive of Colonialism: Germany and Namibia

Photo-essay The Visual Archive of Colonialism: Germany and Namibia George Steinmetz and Julia Hell Colonial memories and images occupy a paradoxi- cal place in Germany. This is due in part to the peculiarities of German colo- nial history, but it also reflects another aspect of German exceptionalism — the legacy of Nazism and the Holocaust. In recent years German colonialism in Southwest Africa (Namibia) has been widely discussed, especially with respect to the attempted extermination of the Ovaherero people in 1904. For reasons explored in this article, these discussions of Germany’s involvement in Southwest Africa have created new and unexpected discursive connections that are reshap- ing colonial memories in both Germany and Namibia. One possible outcome could be a belated decolonization of the landscape of colonial memory in both countries. Postwar Germany was long preoccupied with its National Socialist prehistory; the German colonial past has only started to come into focus more recently.1 The years 2004 – 5 saw numerous commemorative events around the centenary of the 1904 German genocide of the Namibian Ovaherero people and the completion of the controversial Berlin Holocaust Memorial. On one level this is mere coinci- dence. At the same time, there is an increasing entanglement of these two central political topics. But little research has been done on the visual archive of German colonialism, in contrast to the extensive studies made of the public circulation of Thanks to Johannes von Moltke for helping us with the research into the November 2004 von Trotha – Maherero meeting. 1. For a discussion of the ways in which the formerly divided country’s Nazi past was thematized anew after 1989, see Julia Hell and Johannes von Moltke, “Unification Effects: Imaginary Land- scapes of the Berlin Republic,” in “The Cultural Logics of the Berlin Republic,” ed. -

Berlin Zentral Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf

Berlin zentral Marzahn Pankow SEKIS Selbsthilfe-Kontakt- und Beratungsstelle KIS Kontakt- und Informationsstelle Selbsthilfe Kontakt- und Informationsstelle Marzahn-Hellersdorf für Selbsthilfe im Stadtteilzentrum Pankow Bismarckstr. 101 | 10625 Berlin Alt-Marzahn 59 A | 12685 Berlin Schönholzer Str. 10 | 13187 Berlin Tel 892 66 02 Tel 54 25 103 Tel 499 870 910 Fax 890 285 40 Fax 540 68 85 Mail [email protected] Mail [email protected] Mail [email protected] www.kisberlin.de www.sekis.de www.wuhletal.de Mo + Mi 15-18, Do 10-13 Uhr Mo 12-16, Mi 10-14 und Do 14-18 Uhr Mo 13-17, Di 15-19, Fr 9-13 Uhr und nach Vereinbarung Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf Pankow-Buch SelbsthilfeKontaktstelle Mitte Selbsthilfe- und Stadtteilzentrum Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf SEKIS im Bucher Bürgerhaus Bismarckstr. 101 | 10625 Berlin Selbsthilfe Kontakt- und Beratungsstelle Mitte Franz-Schmidt-Str. 8-10 | 13125 Berlin Tel 892 66 02 - StadtRand gGmbH Tel 941 54 26 Mail [email protected] Perleberger Str. 44 | 10559 Berlin Fax 941 54 29 www.sekis.de Tel 394 63 64 Mail [email protected] Mo 12-16, Mi 10-14, Do 14-18 Uhr Tax 394 64 85 www.albatrosggmbh.de Mail [email protected] Di 15-18, Do + Fr 10-13 Uhr www.stadtrand-berlin.de Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg Mo, Di 10-14, Do 15-18 Uhr Selbsthilfe-Treffpunkt Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg Mi 10-13 Uhr (in türkischer Sprache) Reinickendorf Boxhagenerstr. 89 | 10245 Berlin und nach Vereinbarung Tel 291 83 48 Selbsthilfe- und Stadtteilzentrum Reinickendorf, Fax 290 49 662 Neukölln Süd Günter-Zemla-Haus Mail [email protected] Eichhorster Weg 32 | 13435 Berlin www.selbsthilfe-treffpunkt.de Selbsthilfe- und Stadtteilzentrum Neukölln-Süd Tel 416 48 42 Di + Fr 10-13; Mi + Do 15-18 Uhr Lipschitzallee 80 | 12353 Berlin Fax 41 74 57 53 Tel 605 66 00 Mail [email protected] Hohenschönhausen Fax 605 68 99 www.unionhilfswerk.de/selbsthilfe Mail [email protected] Di + Do 14-18, Mi + Fr 10-14 Uhr Selbsthilfe Kontakt- und Beratungsstelle - Horizont www.selbsthilfe-neukoelln.de Ahrenshooper Str.