Survivability of Copper Projectiles During Hypervelocity Impacts in Porous

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LCROSS (Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite) Observation Campaign: Strategies, Implementation, and Lessons Learned

Space Sci Rev DOI 10.1007/s11214-011-9759-y LCROSS (Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite) Observation Campaign: Strategies, Implementation, and Lessons Learned Jennifer L. Heldmann · Anthony Colaprete · Diane H. Wooden · Robert F. Ackermann · David D. Acton · Peter R. Backus · Vanessa Bailey · Jesse G. Ball · William C. Barott · Samantha K. Blair · Marc W. Buie · Shawn Callahan · Nancy J. Chanover · Young-Jun Choi · Al Conrad · Dolores M. Coulson · Kirk B. Crawford · Russell DeHart · Imke de Pater · Michael Disanti · James R. Forster · Reiko Furusho · Tetsuharu Fuse · Tom Geballe · J. Duane Gibson · David Goldstein · Stephen A. Gregory · David J. Gutierrez · Ryan T. Hamilton · Taiga Hamura · David E. Harker · Gerry R. Harp · Junichi Haruyama · Morag Hastie · Yutaka Hayano · Phillip Hinz · Peng K. Hong · Steven P. James · Toshihiko Kadono · Hideyo Kawakita · Michael S. Kelley · Daryl L. Kim · Kosuke Kurosawa · Duk-Hang Lee · Michael Long · Paul G. Lucey · Keith Marach · Anthony C. Matulonis · Richard M. McDermid · Russet McMillan · Charles Miller · Hong-Kyu Moon · Ryosuke Nakamura · Hirotomo Noda · Natsuko Okamura · Lawrence Ong · Dallan Porter · Jeffery J. Puschell · John T. Rayner · J. Jedadiah Rembold · Katherine C. Roth · Richard J. Rudy · Ray W. Russell · Eileen V. Ryan · William H. Ryan · Tomohiko Sekiguchi · Yasuhito Sekine · Mark A. Skinner · Mitsuru Sôma · Andrew W. Stephens · Alex Storrs · Robert M. Suggs · Seiji Sugita · Eon-Chang Sung · Naruhisa Takatoh · Jill C. Tarter · Scott M. Taylor · Hiroshi Terada · Chadwick J. Trujillo · Vidhya Vaitheeswaran · Faith Vilas · Brian D. Walls · Jun-ihi Watanabe · William J. Welch · Charles E. Woodward · Hong-Suh Yim · Eliot F. Young Received: 9 October 2010 / Accepted: 8 February 2011 © The Author(s) 2011. -

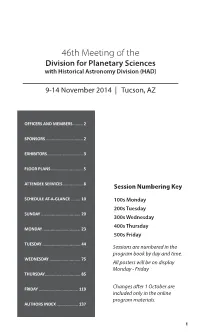

PDF Program Book

46th Meeting of the Division for Planetary Sciences with Historical Astronomy Division (HAD) 9-14 November 2014 | Tucson, AZ OFFICERS AND MEMBERS ........ 2 SPONSORS ............................... 2 EXHIBITORS .............................. 3 FLOOR PLANS ........................... 5 ATTENDEE SERVICES ................. 8 Session Numbering Key SCHEDULE AT-A-GLANCE ........ 10 100s Monday 200s Tuesday SUNDAY ................................. 20 300s Wednesday 400s Thursday MONDAY ................................ 23 500s Friday TUESDAY ................................ 44 Sessions are numbered in the program book by day and time. WEDNESDAY .......................... 75 All posters will be on display Monday - Friday THURSDAY.............................. 85 FRIDAY ................................. 119 Changes after 1 October are included only in the online program materials. AUTHORS INDEX .................. 137 1 DPS OFFICERS AND MEMBERS Current DPS Officers Heidi Hammel Chair Bonnie Buratti Vice-Chair Athena Coustenis Secretary Andrew Rivkin Treasurer Nick Schneider Education and Public Outreach Officer Vishnu Reddy Press Officer Current DPS Committee Members Rosaly Lopes Term Expires November 2014 Robert Pappalardo Term Expires November 2014 Ralph McNutt Term Expires November 2014 Ross Beyer Term Expires November 2015 Paul Withers Term Expires November 2015 Julie Castillo-Rogez Term Expires October 2016 Jani Radebaugh Term Expires October 2016 SPONSORS 2 EXHIBITORS Platinum Exhibitor Silver Exhibitors 3 EXHIBIT BOOTH ASSIGNMENTS 206 Applied -

LCROSS (Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite) Observation Campaign: Strategies, Implementation, and Lessons Learned

Space Sci Rev (2012) 167:93–140 DOI 10.1007/s11214-011-9759-y LCROSS (Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite) Observation Campaign: Strategies, Implementation, and Lessons Learned Jennifer L. Heldmann · Anthony Colaprete · Diane H. Wooden · Robert F. Ackermann · David D. Acton · Peter R. Backus · Vanessa Bailey · Jesse G. Ball · William C. Barott · Samantha K. Blair · Marc W. Buie · Shawn Callahan · Nancy J. Chanover · Young-Jun Choi · Al Conrad · Dolores M. Coulson · Kirk B. Crawford · Russell DeHart · Imke de Pater · Michael Disanti · James R. Forster · Reiko Furusho · Tetsuharu Fuse · Tom Geballe · J. Duane Gibson · David Goldstein · Stephen A. Gregory · David J. Gutierrez · Ryan T. Hamilton · Taiga Hamura · David E. Harker · Gerry R. Harp · Junichi Haruyama · Morag Hastie · Yutaka Hayano · Phillip Hinz · Peng K. Hong · Steven P. James · Toshihiko Kadono · Hideyo Kawakita · Michael S. Kelley · Daryl L. Kim · Kosuke Kurosawa · Duk-Hang Lee · Michael Long · Paul G. Lucey · Keith Marach · Anthony C. Matulonis · Richard M. McDermid · Russet McMillan · Charles Miller · Hong-Kyu Moon · Ryosuke Nakamura · Hirotomo Noda · Natsuko Okamura · Lawrence Ong · Dallan Porter · Jeffery J. Puschell · John T. Rayner · J. Jedadiah Rembold · Katherine C. Roth · Richard J. Rudy · Ray W. Russell · Eileen V. Ryan · William H. Ryan · Tomohiko Sekiguchi · Yasuhito Sekine · Mark A. Skinner · Mitsuru Sôma · Andrew W. Stephens · Alex Storrs · Robert M. Suggs · Seiji Sugita · Eon-Chang Sung · Naruhisa Takatoh · Jill C. Tarter · Scott M. Taylor · Hiroshi Terada · Chadwick J. Trujillo · Vidhya Vaitheeswaran · Faith Vilas · Brian D. Walls · Jun-ihi Watanabe · William J. Welch · Charles E. Woodward · Hong-Suh Yim · Eliot F. Young Received: 9 October 2010 / Accepted: 8 February 2011 / Published online: 18 March 2011 © The Author(s) 2011. -

Impact Impacts on the Moon, Mercury, and Europa

IMPACT IMPACTS ON THE MOON, MERCURY, AND EUROPA A dissertation submitted to the graduate division of the University of Hawai`i at M¯anoain partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in GEOLOGY AND GEOPHYSICS March 2020 By Emily S. Costello Dissertation Committee: Paul G. Lucey, Chairperson S. Fagents B. Smith-Konter N. Frazer P. Gorham c Copyright 2020 by Emily S. Costello All Rights Reserved ii This dissertation is dedicated to the Moon, who has fascinated our species for millennia and fascinates us still. iii Acknowledgements I wish to thank my family, who have loved and nourished me, and Dr. Rebecca Ghent for opening the door to planetary science to me, for teaching me courage and strength through example, and for being a true friend. I wish to thank my advisor, Dr. Paul Lucey for mentoring me in the art of concrete impressionism. I could not have hoped for a more inspiring mentor. I finally extend my heartfelt thanks to Dr. Michael Brodie, who erased the line between \great scientist" and \great artist" that day in front of a room full of humanities students - erasing, in my mind, the barrier between myself and the beauty of physics. iv Abstract In this work, I reconstitute and improve upon an Apollo-era statistical model of impact gardening (Gault et al. 1974) and validate the model against the gardening implied by remote sensing and analysis of Apollo cores. My major contribution is the modeling and analysis of the influence of secondary crater-forming impacts, which dominate impact gardening. -

Evidence for Exposed Water Ice in the Moon's

Icarus 255 (2015) 58–69 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Icarus journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/icarus Evidence for exposed water ice in the Moon’s south polar regions from Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter ultraviolet albedo and temperature measurements ⇑ Paul O. Hayne a, , Amanda Hendrix b, Elliot Sefton-Nash c, Matthew A. Siegler a, Paul G. Lucey d, Kurt D. Retherford e, Jean-Pierre Williams c, Benjamin T. Greenhagen a, David A. Paige c a Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91109, United States b Planetary Science Institute, Pasadena, CA 91106, United States c University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095, United States d University of Hawaii, Manoa, HI 96822, United States e Southwest Research Institute, Boulder, CO 80302, United States article info abstract Article history: We utilize surface temperature measurements and ultraviolet albedo spectra from the Lunar Received 25 July 2014 Reconnaissance Orbiter to test the hypothesis that exposed water frost exists within the Moon’s shad- Revised 26 March 2015 owed polar craters, and that temperature controls its concentration and spatial distribution. For locations Accepted 30 March 2015 with annual maximum temperatures T greater than the H O sublimation temperature of 110 K, we Available online 3 April 2015 max 2 find no evidence for exposed water frost, based on the LAMP UV spectra. However, we observe a strong change in spectral behavior at locations perennially below 110 K, consistent with cold-trapped ice on Keywords: the surface. In addition to the temperature association, spectral evidence for water frost comes from Moon the following spectral features: (a) decreasing Lyman- albedo, (b) decreasing ‘‘on-band’’ (129.57– Ices a Ices, UV spectroscopy 155.57 nm) albedo, and (c) increasing ‘‘off-band’’ (155.57–189.57 nm) albedo. -

Observing the Lunar Libration Zones

Observing the Lunar Libration Zones Alexander Vandenbohede 2005 Many Look, Few Observe (Harold Hill, 1991) Table of Contents Introduction 1 1 Libration and libration zones 3 2 Mare Orientale 14 3 South Pole 18 4 Mare Australe 23 5 Mare Marginis and Mare Smithii 26 6 Mare Humboldtianum 29 7 North Pole 33 8 Oceanus Procellarum 37 Appendix I: Observational Circumstances and Equipment 43 Appendix II: Time Stratigraphical Table of the Moon and the Lunar Geological Map 44 Appendix III: Bibliography 46 Introduction – Why Observe the Libration Zones? You might think that, because the Moon always keeps the same hemisphere turned towards the Earth as a consequence of its captured rotation, we always see the same 50% of the lunar surface. Well, this is not true. Because of the complicated motion of the Moon (see chapter 1) we can see a little bit around the east and west limb and over the north and south poles. The result is that we can observe 59% of the lunar surface. This extra 9% of lunar soil is called the libration zones because the motion, a gentle wobbling of the Moon in the Earth’s sky responsible for this, is called libration. In spite of the remainder of the lunar Earth-faced side, observing and even the basic task of identifying formations in the libration zones is not easy. The formations are foreshortened and seen highly edge-on. Obviously, you will need to know when libration favours which part of the lunar limb and how much you can look around the Moon’s limb. -

Crater Cabeus As Possible Cold Trap for Volatiles Near South Pole of the Moon

41st Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (2010) 1779.pdf CRATER CABEUS AS POSSIBLE COLD TRAP FOR VOLATILES NEAR SOUTH POLE OF THE MOON. Kozlova E.A., Lazarev E.N., Sternberg State Astronomical Institute, Moscow University, Russia, Moscow, Universitetski pr., 13, 199992. [email protected], [email protected] Introduction: Crater Cabeus has been cho- crater is illuminated during 25% of the Moon’s sen by NASA as a target for impact experiment of day. The inner walls of the crater are illuminated LCROSS mission [1]. In the cloud formed after by direct sunlight during more than 30% of the the impact of Centaur stage and LCROSS there Moon’s day. The constantly shadowed area of the have been discovered traces of water appearance. crater is situated in the west part of the crater and In 1998 in Polar districts of the Moon there have coincides with small impact crater on the bottom been found regions with excesses of hydrogen of Cabeus. The time during which this area is il- that were registered by means of neutron spec- luminated by direct sunlight is equal to no more trometer of Lunar Prospector [2]. Significant parts than 15% of the Moon’s day. of such places coincided with impact craters. En- hanced content of hydrogen has also been found in the neighborhood of crater Cabeus where it was equal to 129 ppm (the average level of hydrogen content in the Moon’s soil is equal to 50 ppm). Therefore this crater began to be considered as one of the possible “cold traps” for volatiles on the Moon. -

Accessible Carbon on the Moon

ACCESSIBLE CARBON ON THE MOON APREPRINT Kevin M. Cannon Department of Geology and Geological Engineering & Space Resources Program Colorado School of Mines Golden, CO 80401 [email protected] April 27, 2021 ABSTRACT Carbon is one of the most essential elements to support a sustained human presence in space, and more immediately, several large-scale methalox-based transport systems will begin operating in the near future. This raises the question of whether indigenous carbon on the Moon is abundant and concentrated to the extent where it could be used as a viable resource including as propellant. Here, I assess potential sources of lunar carbon based on previous work focused on polar water ice. A simplified model is used to estimate the temperature-dependent Carbon Content of Ices at the lunar poles, and this is combined with remote sensing data to estimate the total amount of carbon and generate a Carbon Favorability Index that highlights promising deposits for future ground-based prospecting. Hotspots in the index maps are identified, and nearby staging areas are analyzed using quantitative models of trafficability and solar irradiance. Overall, the Moon is extremely poor in carbon sources compared to more abundant and readily accessible options at Mars. However, a handful of polar regions may contain appreciable amounts of subsurface carbon-bearing ices that could serve as a rich source in the near term, but would be easily exhausted on longer timescales. Four of those regions were found to have safe nearby staging areas with equatorial-like illumination at a modest height above the surface. Any one of these sites could yield enough C, H and O to produce propellant for hundreds of refuelings of a large spacecraft. -

MISION ARTEMIS 3 Table of Contents 1. Introduction 2. Operational Part 2.1 Space Launch System 2.2 Orion 2.3 Moon Landing 2.4 Earth Landing 2.5 Rover 3

i MISION ARTEMIS 3 Table of contents 1. Introduction 2. Operational Part 2.1 Space Launch System 2.2 Orion 2.3 Moon Landing 2.4 Earth Landing 2.5 Rover 3. Social Part 3.1 NASA Coin 4. Scope 4.1 Risks of the Mision 4.2 Education 4.3 Finance and Legislation 5. Authors 6. Enterprises 7. Acknowledgements 1. Introduction The third Artemis Mission planned for 2024 is scheduled to be the second manned mission of the Orion spacecraft with the Space Launch System. It will take its crew into lunar orbit, where it will dock with the Gateway (Lunar Space Station). The crew will check the gateway cabin and the human landing system before boarding the Moon descent module. It will be the first moon landing since the Apollo missions and will be performed by a woman. 2. Operational Part Of The Mission 2.1 Space Launch System The space launch system aims to bring the first woman to the Moon. The rocket will take the Orion spacecraft to the gateway for docking. The key aspects are: Enough thrust to bring crew and supplies to the gateway Safe transport of crew members 2.2 Orion The Orion spacecraft will be the main feature of Artemis 3. It will take 4 crew members to the gateway. Also, the Orion Module will take the crew to the Moon and back. The key aspects are: Safe transport of crew members to the Gateway and to the Moon and back. Transport enough resources for a few days of exploration on de moon´s surface. -

And X-Band Bistatic Observations of South Polar Craters on the Moon

EPSC Abstracts Vol. 12, EPSC2018-729, 2018 European Planetary Science Congress 2018 EEuropeaPn PlanetarSy Science CCongress c Author(s) 2018 Mini-RF S- and X-band Bistatic Observations of South Polar Craters on the Moon G. W. Patterson (1), P. Prem (1), A. M. Stickle (1), J. T. S. Cahill (1), Land the Mini-RF Team (1) Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, Laurel, MD ([email protected]). Abstract Laboratory data and analog experiments at optical wavelengths have shown that the scattering Mini-RF S-band bistatic observations of Cabeus properties of lunar materials (e.g., CPR) can be crater floor materials display a clear opposition sensitive to variations in phase angle [6-8]. This response consistent with the presence of water ice. sensitivity manifests as an opposition effect and Initial X-band bistatic observations of Cabeus and likely involves contributions from shadow hiding at Amundsen crater floor materials do not show a low angles and coherent backscatter near 0°. Analog similar response. This could indicate that, if water ice experiments and theoretical work have shown that is present in Cabeus crater floor materials, it is buried the scattering properties of water ice are also beneath ~0.5 m of regolith that does not include sensitive to variations in phase angle, with an radar-detectible deposits of water ice. opposition effect that it is tied primarily to coherent backscatter [9-11]. Differences in the character of the opposition response of these materials offer an 1. Introduction opportunity to differentiate between them, an issue Mini-RF aboard NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance that has been problematic for radar studies of the Orbiter (LRO) is a hybrid dual-polarized synthetic Moon that use a monostatic architecture [12,13]. -

Using Microwaves for Extracting Water from the Moon COMSOL Conference October 9, 2009 Boston, MA

Presented at the COMSOL Conference 2009 Boston Using Microwaves for Extracting Water from the Moon COMSOL Conference October 9, 2009 Boston, MA Edwin Ethridge, PhD, Principal Investigator Materials & Processes Laboratory NASA-MSFC-EM40, Huntsville, AL William Kaukler, PhD Department of Chemistry The University of Alabama in Huntsville Frank Hepburn Materials & Processes Laboratory NASA-MSFC-EM20, Huntsville, AL Copyright Notice: This material is declared a work of the U.S. Government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. Water is one of the Most Plentiful Compounds in the Universe • Earth’s water came from comets early in its history. • Mars has vast quantities of water not only at the poles but also at lower latitudes (>550). • Significant quantities of water are present on several moons of Jupiter (Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto), Saturn (Enceladus), and Neptune (Titon). Chronology of “Water on the Moon” 1959, prior to Apollo, scientists speculated that there should be some residual water on the moon from cometary impacts. Apollo found “no water”. 1994, the SDI-NASA Clementine spacecraft mapped the surface. Microwave radio signals from South pole shadowed craters were consistent with the presence of water. 1998 – Prospector - Neutron Spectrometer – high H concentrations at poles September 2009 – water observed at diverse locations of moon Chandrayaan-1 - Moon Mineralogy Mapper (M3) Cassini - Visual and Infrared Mapping Spectrometer (VIMS) EPOXI spacecraft - High-Resolution Infrared Imaging Spectrometer October -

Water Within a Permanently Shadowed Lunar Crater: Further LCROSS Modeling and Analysis

Draft version September 14, 2020 Typeset using LATEX default style in AASTeX62 Water Within a Permanently Shadowed Lunar Crater: Further LCROSS Modeling and Analysis Kristen M. Luchsinger1 | Nancy J. Chanover1 | Paul D. Strycker2 | 1Astronomy Department, New Mexico State University, Las Cruces, NM, USA 2Concordia University Wisconsin, Mequon, WI, USA ABSTRACT The 2009 Lunar CRater Observation and Sensing Satellite (LCROSS) impact mission detected water ice absorption using spectroscopic observations of the impact-generated debris plume taken by the Shepherding Spacecraft, confirming an existing hypothesis regarding the existence of water ice in permanently shadowed regions within Cabeus crater. Ground-based observations in support of the mission were able to further constrain the mass of the debris plume and the concentration of the water ice ejected during the impact. In this work, we explore additional constraints on the initial conditions of the pre-impact lunar sediment required in order to produce a plume model that is consistent with the ground-based observations. We match the observed debris plume lightcurve using a layer of dirty ice with an ice concentration that increases with depth, a layer of pure regolith, and a layer of material at about 6 meters below the lunar surface that would otherwise have been visible in the plume but has a high enough tensile strength to resist excavation. Among a few possible materials, a mixture of regolith and ice with a sufficiently high ice concentration could plausibly produce such a behavior. The vertical albedo profiles used in the best fit model allows us to calculate a pre-impact mass of water ice within Cabeus crater of 5 ± 3:0 × 1011 kg and a mass concentration of water in the lunar sediment of 8:2 ± 0:001 %wt, assuming a water ice albedo of 0.8 and a lunar regolith density of 1.5 g cm−3, or a mass concentration of water of 4:3 ± 0:01 %wt, assuming a lunar regolith density of 3.0.