Water Within a Permanently Shadowed Lunar Crater: Further LCROSS Modeling and Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exploring the Bombardment History of the Moon

EXPLORING THE BOMBARDMENT HISTORY OF THE MOON Community White Paper to the Planetary Decadal Survey, 2011-2020 September 15, 2009 Primary Author: William F. Bottke Center for Lunar Origin and Evolution (CLOE) NASA Lunar Science Institute at the Southwest Research Institute 1050 Walnut St., Suite 300 Boulder, CO 80302 Tel: (303) 546-6066 [email protected] Co-Authors/Endorsers: Carlton Allen (NASA JSC) Mahesh Anand (Open U., UK) Nadine Barlow (NAU) Donald Bogard (NASA JSC) Gwen Barnes (U. Idaho) Clark Chapman (SwRI) Barbara A. Cohen (NASA MSFC) Ian A. Crawford (Birkbeck College London, UK) Andrew Daga (U. North Dakota) Luke Dones (SwRI) Dean Eppler (NASA JSC) Vera Assis Fernandes (Berkeley Geochronlogy Center and U. Manchester) Bernard H. Foing (SMART-1, ESA RSSD; Dir., Int. Lunar Expl. Work. Group) Lisa R. Gaddis (US Geological Survey) 1 Jim N. Head (Raytheon) Fredrick P. Horz (LZ Technology/ESCG) Brad Jolliff (Washington U., St Louis) Christian Koeberl (U. Vienna, Austria) Michelle Kirchoff (SwRI) David Kring (LPI) Harold F. (Hal) Levison (SwRI) Simone Marchi (U. Padova, Italy) Charles Meyer (NASA JSC) David A. Minton (U. Arizona) Stephen J. Mojzsis (U. Colorado) Clive Neal (U. Notre Dame) Laurence E. Nyquist (NASA JSC) David Nesvorny (SWRI) Anne Peslier (NASA JSC) Noah Petro (GSFC) Carle Pieters (Brown U.) Jeff Plescia (Johns Hopkins U.) Mark Robinson (Arizona State U.) Greg Schmidt (NASA Lunar Science Institute, NASA Ames) Sen. Harrison H. Schmitt (Apollo 17 Astronaut; U. Wisconsin-Madison) John Spray (U. New Brunswick, Canada) Sarah Stewart-Mukhopadhyay (Harvard U.) Timothy Swindle (U. Arizona) Lawrence Taylor (U. Tennessee-Knoxville) Ross Taylor (Australian National U., Australia) Mark Wieczorek (Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris, France) Nicolle Zellner (Albion College) Maria Zuber (MIT) 2 The Moon is unique. -

LCROSS (Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite) Observation Campaign: Strategies, Implementation, and Lessons Learned

Space Sci Rev DOI 10.1007/s11214-011-9759-y LCROSS (Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite) Observation Campaign: Strategies, Implementation, and Lessons Learned Jennifer L. Heldmann · Anthony Colaprete · Diane H. Wooden · Robert F. Ackermann · David D. Acton · Peter R. Backus · Vanessa Bailey · Jesse G. Ball · William C. Barott · Samantha K. Blair · Marc W. Buie · Shawn Callahan · Nancy J. Chanover · Young-Jun Choi · Al Conrad · Dolores M. Coulson · Kirk B. Crawford · Russell DeHart · Imke de Pater · Michael Disanti · James R. Forster · Reiko Furusho · Tetsuharu Fuse · Tom Geballe · J. Duane Gibson · David Goldstein · Stephen A. Gregory · David J. Gutierrez · Ryan T. Hamilton · Taiga Hamura · David E. Harker · Gerry R. Harp · Junichi Haruyama · Morag Hastie · Yutaka Hayano · Phillip Hinz · Peng K. Hong · Steven P. James · Toshihiko Kadono · Hideyo Kawakita · Michael S. Kelley · Daryl L. Kim · Kosuke Kurosawa · Duk-Hang Lee · Michael Long · Paul G. Lucey · Keith Marach · Anthony C. Matulonis · Richard M. McDermid · Russet McMillan · Charles Miller · Hong-Kyu Moon · Ryosuke Nakamura · Hirotomo Noda · Natsuko Okamura · Lawrence Ong · Dallan Porter · Jeffery J. Puschell · John T. Rayner · J. Jedadiah Rembold · Katherine C. Roth · Richard J. Rudy · Ray W. Russell · Eileen V. Ryan · William H. Ryan · Tomohiko Sekiguchi · Yasuhito Sekine · Mark A. Skinner · Mitsuru Sôma · Andrew W. Stephens · Alex Storrs · Robert M. Suggs · Seiji Sugita · Eon-Chang Sung · Naruhisa Takatoh · Jill C. Tarter · Scott M. Taylor · Hiroshi Terada · Chadwick J. Trujillo · Vidhya Vaitheeswaran · Faith Vilas · Brian D. Walls · Jun-ihi Watanabe · William J. Welch · Charles E. Woodward · Hong-Suh Yim · Eliot F. Young Received: 9 October 2010 / Accepted: 8 February 2011 © The Author(s) 2011. -

Lunar Water ISRU Measurement Study (LWIMS): Establishing a Measurement Plan for Identifi Cation and Characterization of a Water Reserve

NASA/TM-20205008626 Lunar Water ISRU Measurement Study (LWIMS): Establishing a Measurement Plan for Identifi cation and Characterization of a Water Reserve Julie Kleinhenz Glenn Research Center, Cleveland, Ohio Amy McAdam Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Maryland Anthony Colaprete Ames Research Center, Moff ett Field, California David Beaty Jet Propulsion Laboratory/California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, California Barbara Cohen Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Maryland Pamela Clark Jet Propulsion Laboratory/California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, California John Gruener Johnson Space Center, Houston, Texas Jason Schuler Kennedy Space Center, Kennedy Space Center, Florida Kelsey Young Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Maryland October 2020 NASA STI Program . in Profi le Since its founding, NASA has been dedicated • CONTRACTOR REPORT. Scientifi c and to the advancement of aeronautics and space science. technical fi ndings by NASA-sponsored The NASA Scientifi c and Technical Information (STI) contractors and grantees. Program plays a key part in helping NASA maintain this important role. • CONFERENCE PUBLICATION. Collected papers from scientifi c and technical conferences, symposia, seminars, or other The NASA STI Program operates under the auspices meetings sponsored or co-sponsored by NASA. of the Agency Chief Information Offi cer. It collects, organizes, provides for archiving, and disseminates • SPECIAL PUBLICATION. Scientifi c, NASA’s STI. The NASA STI Program provides access technical, or historical information from to the NASA Technical Report Server—Registered NASA programs, projects, and missions, often (NTRS Reg) and NASA Technical Report Server— concerned with subjects having substantial Public (NTRS) thus providing one of the largest public interest. collections of aeronautical and space science STI in the world. -

Untangling the Formation and Liberation of Water in the Lunar Regolith

Untangling the formation and liberation of water in the lunar regolith Cheng Zhua,b,1, Parker B. Crandalla,b,1, Jeffrey J. Gillis-Davisc,2, Hope A. Ishiic, John P. Bradleyc, Laura M. Corleyc, and Ralf I. Kaisera,b,2 aDepartment of Chemistry, University of Hawai‘iatManoa, Honolulu, HI 96822; bW. M. Keck Laboratory in Astrochemistry, University of Hawai‘iatManoa, Honolulu, HI 96822; and cHawai‘i Institute of Geophysics and Planetology, University of Hawai‘iatManoa, Honolulu, HI 96822 Edited by Mark H. Thiemens, University of California at San Diego, La Jolla, CA, and approved April 24, 2019 (received for review November 15, 2018) −8 −6 The source of water (H2O) and hydroxyl radicals (OH), identified between 10 and 10 torr observed either an ν(O−H) stretching − − on the lunar surface, represents a fundamental, unsolved puzzle. mode in the 2.70 μm (3,700 cm 1) to 3.33 μm (3,000 cm 1) region The interaction of solar-wind protons with silicates and oxides has exploiting infrared spectroscopy (7, 25, 26) or OH/H2Osignature been proposed as a key mechanism, but laboratory experiments using secondary-ion mass spectrometry (27) and valence electron yield conflicting results that suggest that proton implantation energy loss spectroscopy (VEEL) (28). However, contradictory alone is insufficient to generate and liberate water. Here, we dem- studies yielded no evidence of H2O/OH in proton-bombarded onstrate in laboratory simulation experiments combined with minerals in experiments performed under ultrahigh vacuum − − imaging studies that water can be efficiently generated and re- (UHV) (10 10 to 10 9 torr) (29). -

Planning a Mission to the Lunar South Pole

Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter: (Diviner) Audience Planning a Mission to Grades 9-10 the Lunar South Pole Time Recommended 1-2 hours AAAS STANDARDS Learning Objectives: • 12A/H1: Exhibit traits such as curiosity, honesty, open- • Learn about recent discoveries in lunar science. ness, and skepticism when making investigations, and value those traits in others. • Deduce information from various sources of scientific data. • 12E/H4: Insist that the key assumptions and reasoning in • Use critical thinking to compare and evaluate different datasets. any argument—whether one’s own or that of others—be • Participate in team-based decision-making. made explicit; analyze the arguments for flawed assump- • Use logical arguments and supporting information to justify decisions. tions, flawed reasoning, or both; and be critical of the claims if any flaws in the argument are found. • 4A/H3: Increasingly sophisticated technology is used Preparation: to learn about the universe. Visual, radio, and X-ray See teacher procedure for any details. telescopes collect information from across the entire spectrum of electromagnetic waves; computers handle Background Information: data and complicated computations to interpret them; space probes send back data and materials from The Moon’s surface thermal environment is among the most extreme of any remote parts of the solar system; and accelerators give planetary body in the solar system. With no atmosphere to store heat or filter subatomic particles energies that simulate conditions in the Sun’s radiation, midday temperatures on the Moon’s surface can reach the stars and in the early history of the universe before 127°C (hotter than boiling water) whereas at night they can fall as low as stars formed. -

Rare Astronomical Sights and Sounds

Jonathan Powell Rare Astronomical Sights and Sounds The Patrick Moore The Patrick Moore Practical Astronomy Series More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/3192 Rare Astronomical Sights and Sounds Jonathan Powell Jonathan Powell Ebbw Vale, United Kingdom ISSN 1431-9756 ISSN 2197-6562 (electronic) The Patrick Moore Practical Astronomy Series ISBN 978-3-319-97700-3 ISBN 978-3-319-97701-0 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-97701-0 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018953700 © Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2018 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors, and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

Impact Cratering in the Solar System

Impact Cratering in the Solar System Michelle Kirchoff Lunar and Planetary Institute University of Houston - Clear Lake Physics Seminar March 24, 2008 Outline What is an impact crater? Why should we care about impact craters? Inner Solar System Outer Solar System Conclusions Open Questions What is an impact crater? Basically a hole in the ground… Barringer Meteor Crater (Earth) Bessel Crater (Moon) Diameter = 1.2 km Diameter = 16 km Depth = 200 m Depth = 2 km www.lpi.usra.edu What creates an “impact” crater? •Galileo sees circular features on Moon & realizes they are depressions (1610) •In 1600-1800’s many think they are volcanic features: look similar to extinct volcanoes on Earth; some even claim to see volcanic eruptions; space is empty (meteorites not verified until 1819 by Chladni) •G.K. Gilbert (1893) first serious support for lunar craters from impacts (geology and experiments) •On Earth Barringer (Meteor) crater recognized as created by impact by Barringer (1906) •Opik (1916) - impacts are high velocity, thus create circular craters at most impact angles Melosh, 1989 …High-Velocity Impacts! www.lpl.arizona.edu/SIC/impact_cratering/Chicxulub/Animation.gif Physics of Impact Cratering Understand how stress (or shock) waves propagate through material in 3 stages: 1. Contact and Compression 2. Excavation 3. Modification www.psi.edu/explorecraters/background.htm Hugoniot Equations Derived by P.H. Hugoniot (1887) to describe shock fronts using conservation of mass, momentum and energy across the discontinuity. equation (U-up) = oU of state P-Po = oupU E-Eo = (P+Po)(Vo-V)/2 P - pressure U - shock velocity up - particle velocity E - specific internal energy V = 1/specific volume) Understanding Crater Formation laboratory large simulations explosives (1950’s) (1940’s) www.nasa.gov/centers/ames/ numerical simulations (1960’s) www.lanl.gov/ Crater Morphology • Simple • Complex • Central peak/pit • Peak ring www3.imperial.ac. -

March 21–25, 2016

FORTY-SEVENTH LUNAR AND PLANETARY SCIENCE CONFERENCE PROGRAM OF TECHNICAL SESSIONS MARCH 21–25, 2016 The Woodlands Waterway Marriott Hotel and Convention Center The Woodlands, Texas INSTITUTIONAL SUPPORT Universities Space Research Association Lunar and Planetary Institute National Aeronautics and Space Administration CONFERENCE CO-CHAIRS Stephen Mackwell, Lunar and Planetary Institute Eileen Stansbery, NASA Johnson Space Center PROGRAM COMMITTEE CHAIRS David Draper, NASA Johnson Space Center Walter Kiefer, Lunar and Planetary Institute PROGRAM COMMITTEE P. Doug Archer, NASA Johnson Space Center Nicolas LeCorvec, Lunar and Planetary Institute Katherine Bermingham, University of Maryland Yo Matsubara, Smithsonian Institute Janice Bishop, SETI and NASA Ames Research Center Francis McCubbin, NASA Johnson Space Center Jeremy Boyce, University of California, Los Angeles Andrew Needham, Carnegie Institution of Washington Lisa Danielson, NASA Johnson Space Center Lan-Anh Nguyen, NASA Johnson Space Center Deepak Dhingra, University of Idaho Paul Niles, NASA Johnson Space Center Stephen Elardo, Carnegie Institution of Washington Dorothy Oehler, NASA Johnson Space Center Marc Fries, NASA Johnson Space Center D. Alex Patthoff, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Cyrena Goodrich, Lunar and Planetary Institute Elizabeth Rampe, Aerodyne Industries, Jacobs JETS at John Gruener, NASA Johnson Space Center NASA Johnson Space Center Justin Hagerty, U.S. Geological Survey Carol Raymond, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Lindsay Hays, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Paul Schenk, -

PDF Program Book

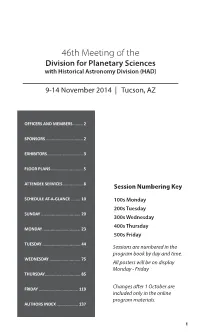

46th Meeting of the Division for Planetary Sciences with Historical Astronomy Division (HAD) 9-14 November 2014 | Tucson, AZ OFFICERS AND MEMBERS ........ 2 SPONSORS ............................... 2 EXHIBITORS .............................. 3 FLOOR PLANS ........................... 5 ATTENDEE SERVICES ................. 8 Session Numbering Key SCHEDULE AT-A-GLANCE ........ 10 100s Monday 200s Tuesday SUNDAY ................................. 20 300s Wednesday 400s Thursday MONDAY ................................ 23 500s Friday TUESDAY ................................ 44 Sessions are numbered in the program book by day and time. WEDNESDAY .......................... 75 All posters will be on display Monday - Friday THURSDAY.............................. 85 FRIDAY ................................. 119 Changes after 1 October are included only in the online program materials. AUTHORS INDEX .................. 137 1 DPS OFFICERS AND MEMBERS Current DPS Officers Heidi Hammel Chair Bonnie Buratti Vice-Chair Athena Coustenis Secretary Andrew Rivkin Treasurer Nick Schneider Education and Public Outreach Officer Vishnu Reddy Press Officer Current DPS Committee Members Rosaly Lopes Term Expires November 2014 Robert Pappalardo Term Expires November 2014 Ralph McNutt Term Expires November 2014 Ross Beyer Term Expires November 2015 Paul Withers Term Expires November 2015 Julie Castillo-Rogez Term Expires October 2016 Jani Radebaugh Term Expires October 2016 SPONSORS 2 EXHIBITORS Platinum Exhibitor Silver Exhibitors 3 EXHIBIT BOOTH ASSIGNMENTS 206 Applied -

Impact Crater Collapse

P1: SKH/tah P2: KKK/mbg QC: KKK/arun T1: KKK March 12, 1999 17:54 Annual Reviews AR081-12 Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 1999. 27:385–415 Copyright c 1999 by Annual Reviews. All rights reserved IMPACT CRATER COLLAPSE H. J. Melosh Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721; e-mail: [email protected] B. A. Ivanov Institute for Dynamics of the Geospheres, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia 117979 KEY WORDS: crater morphology, dynamical weakening, acoustic fluidization, transient crater, central peaks ABSTRACT The detailed morphology of impact craters is now believed to be mainly caused by the collapse of a geometrically simple, bowl-shaped “transient crater.” The transient crater forms immediately after the impact. In small craters, those less than approximately 15 km diameter on the Moon, the steepest part of the rim collapses into the crater bowl to produce a lens of broken rock in an otherwise unmodified transient crater. Such craters are called “simple” and have a depth- to-diameter ratio near 1:5. Large craters collapse more spectacularly, giving rise to central peaks, wall terraces, and internal rings in still larger craters. These are called “complex” craters. The transition between simple and complex craters depends on 1/g, suggesting that the collapse occurs when a strength threshold is exceeded. The apparent strength, however, is very low: only a few bars, and with little or no internal friction. This behavior requires a mechanism for tem- porary strength degradation in the rocks surrounding the impact site. Several models for this process, including acoustic fluidization and shock weakening, have been considered by recent investigations. -

Constraining the Evolutionary History of the Moon and the Inner Solar System: a Case for New Returned Lunar Samples

Space Sci Rev (2019) 215:54 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11214-019-0622-x Constraining the Evolutionary History of the Moon and the Inner Solar System: A Case for New Returned Lunar Samples Romain Tartèse1 · Mahesh Anand2,3 · Jérôme Gattacceca4 · Katherine H. Joy1 · James I. Mortimer2 · John F. Pernet-Fisher1 · Sara Russell3 · Joshua F. Snape5 · Benjamin P. Weiss6 Received: 23 August 2019 / Accepted: 25 November 2019 / Published online: 2 December 2019 © The Author(s) 2019 Abstract The Moon is the only planetary body other than the Earth for which samples have been collected in situ by humans and robotic missions and returned to Earth. Scien- tific investigations of the first lunar samples returned by the Apollo 11 astronauts 50 years ago transformed the way we think most planetary bodies form and evolve. Identification of anorthositic clasts in Apollo 11 samples led to the formulation of the magma ocean concept, and by extension the idea that the Moon experienced large-scale melting and differentiation. This concept of magma oceans would soon be applied to other terrestrial planets and large asteroidal bodies. Dating of basaltic fragments returned from the Moon also showed that a relatively small planetary body could sustain volcanic activity for more than a billion years after its formation. Finally, studies of the lunar regolith showed that in addition to contain- ing a treasure trove of the Moon’s history, it also provided us with a rich archive of the past 4.5 billion years of evolution of the inner Solar System. Further investigations of samples returned from the Moon over the past five decades led to many additional discoveries, but also raised new and fundamental questions that are difficult to address with currently avail- able samples, such as those related to the age of the Moon, duration of lunar volcanism, the Role of Sample Return in Addressing Major Questions in Planetary Sciences Edited by Mahesh Anand, Sara Russell, Yangting Lin, Meenakshi Wadhwa, Kuljeet Kaur Marhas and Shogo Tachibana B R. -

Private Sector Lunar Exploration Hearing

PRIVATE SECTOR LUNAR EXPLORATION HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON SPACE COMMITTEE ON SCIENCE, SPACE, AND TECHNOLOGY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION SEPTEMBER 7, 2017 Serial No. 115–27 Printed for the use of the Committee on Science, Space, and Technology ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://science.house.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 27–174PDF WASHINGTON : 2017 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON SCIENCE, SPACE, AND TECHNOLOGY HON. LAMAR S. SMITH, Texas, Chair FRANK D. LUCAS, Oklahoma EDDIE BERNICE JOHNSON, Texas DANA ROHRABACHER, California ZOE LOFGREN, California MO BROOKS, Alabama DANIEL LIPINSKI, Illinois RANDY HULTGREN, Illinois SUZANNE BONAMICI, Oregon BILL POSEY, Florida ALAN GRAYSON, Florida THOMAS MASSIE, Kentucky AMI BERA, California JIM BRIDENSTINE, Oklahoma ELIZABETH H. ESTY, Connecticut RANDY K. WEBER, Texas MARC A. VEASEY, Texas STEPHEN KNIGHT, California DONALD S. BEYER, JR., Virginia BRIAN BABIN, Texas JACKY ROSEN, Nevada BARBARA COMSTOCK, Virginia JERRY MCNERNEY, California BARRY LOUDERMILK, Georgia ED PERLMUTTER, Colorado RALPH LEE ABRAHAM, Louisiana PAUL TONKO, New York DRAIN LAHOOD, Illinois BILL FOSTER, Illinois DANIEL WEBSTER, Florida MARK TAKANO, California JIM BANKS, Indiana COLLEEN HANABUSA, Hawaii ANDY BIGGS, Arizona CHARLIE CRIST, Florida ROGER W. MARSHALL, Kansas NEAL P. DUNN, Florida CLAY HIGGINS, Louisiana RALPH NORMAN, South Carolina SUBCOMMITTEE ON SPACE HON. BRIAN BABIN, Texas, Chair DANA ROHRABACHER, California AMI BERA, California, Ranking Member FRANK D. LUCAS, Oklahoma ZOE LOFGREN, California MO BROOKS, Alabama DONALD S.