Brexit, the Second World War and Cultural Trauma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brexit, the City, and the Crisis of Conservatism.Indd

VALDAI DISCUSSION CLUB REPORT www.valdaiclub.com BREXIT, THE CITY, AND THE CRISIS OF CONSERVATISM Radhika Desai and Alan Freeman MOSCOW, DECEMBER 2016 Author Radhika Desai Professor at the Department of Political Studies and Director, Geopolitical Economy Research Group, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Canada Alan Freeman Co-Director of the Geopolitical Economy Research Group, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Canada The views and opinions expressed in this Report are those of the authors and do not represent the views of the Valdai Discussion Club, unless explicitly stated otherwise. Contents Cameron’s High Stakes Poker: Staking the Country for Party Gain ..................................................................3 The Campaign: Racism versus Fear.......................................................................................................................5 The Verdict: Protest Against Neoliberal Britain....................................................................................................7 The City’s Brexit Fears .............................................................................................................................................9 What have they done?! The Known Unknowns and the Unknown Unknowns ............................................ 12 British Society’s Neoliberal Faultlines ............................................................................................................... 15 A Broken Political System ................................................................................................................................... -

House of Lords Official Report

Vol. 795 Monday No. 239 21 January 2019 PARLIAMENTARYDEBATES (HANSARD) HOUSE OF LORDS OFFICIAL REPORT ORDEROFBUSINESS Questions Television Licences: Over 75s .........................................................................................493 Health: Chief Medical Officer’s Recommendations .......................................................495 Education: English Baccalaureate ..................................................................................498 Brexit: Cross-Channel Transport....................................................................................500 Zimbabwe Private Notice Question ..................................................................................................502 Trade Bill Committee (1st Day)......................................................................................................506 Leaving the European Union Statement........................................................................................................................557 Poverty: Metrics Question for Short Debate...............................................................................................573 Trade Bill Committee (1st Day) (Continued) ................................................................................589 Lords wishing to be supplied with these Daily Reports should give notice to this effect to the Printed Paper Office. No proofs of Daily Reports are provided. Corrections for the bound volume which Lords wish to suggest to the report of their speeches should be clearly -

13273 PSA Conf Programme 2011 PRINT

Transforming Politics: New Synergies 61st Annual International Conference 18 – 21 April 2011 Novotel London West, London, UK PSA 61st Annual International Conference London, 18 –21 April 2011 www.psa.ac.uk/2011 A Word of Welcome Dear Conference delegate You are extremely welcome to this 61st Conference of the Political Studies Association, held in the UK capital. The recently refurbished Hammersmith Novotel hotel offers high quality conference facilities all under one roof. We are expecting well over 500 delegates, representing over 50 different countries. There are more than 190 panels, as well as the workshops on Monday, building on last year’s innovation, and as a new addition, dedicated posters sessions. There are also three receptions. The Conference theme is ‘Transforming Politics: New Synergies’. Keynote speakers include Professor Carole Pateman, President of APSA, revisiting the concept of participatory democracy and Professor Iain McLean giving the Government and Opposition-sponsored Leonard Schapiro lecture on the subject of coalition and minority government. On Wednesday, our after-dinner speaker is Professor Tony Wright, (UCL and Birkbeck College) former MP and Chair of the Public Administration Select Committee. Amongst other highlights, Professor Vicente Palermo will discuss Anglo-Argentine relations and John Denham MP will talk on ‘English questions’ and the Labour Party’ and Sir Michael Aaronson, former Director General of Save the Children, will be drawing on his experience working in crisis situations to reflect on whether we had a choice in Libya today. Despite the worsening economic and policy environment, this has been a particularly active and successful year for the Association. Overall membership figures, including those for the new Teachers’ Section, continue to rise. -

Anti-Zionism and Antisemitism Cosmopolitan Reflections

Anti-Zionism and Antisemitism Cosmopolitan Reflections David Hirsh Department of Sociology, Goldsmiths, University of London, New Cross, London SE14 6NW, UK The Working Papers Series is intended to initiate discussion, debate and discourse on a wide variety of issues as it pertains to the analysis of antisemitism, and to further the study of this subject matter. Please feel free to submit papers to the ISGAP working paper series. Contact the ISGAP Coordinator or the Editor of the Working Paper Series, Charles Asher Small. Working Paper Hirsh 2007 ISSN: 1940-610X © Institute for the Study of Global Antisemitism and Policy ISGAP 165 East 56th Street, Second floor New York, NY 10022 United States Office Telephone: 212-230-1840 www.isgap.org ABSTRACT This paper aims to disentangle the difficult relationship between anti-Zionism and antisemitism. On one side, antisemitism appears as a pressing contemporary problem, intimately connected to an intensification of hostility to Israel. Opposing accounts downplay the fact of antisemitism and tend to treat the charge as an instrumental attempt to de-legitimize criticism of Israel. I address the central relationship both conceptually and through a number of empirical case studies which lie in the disputed territory between criticism and demonization. The paper focuses on current debates in the British public sphere and in particular on the campaign to boycott Israeli academia. Sociologically the paper seeks to develop a cosmopolitan framework to confront the methodological nationalism of both Zionism and anti-Zionism. It does not assume that exaggerated hostility to Israel is caused by underlying antisemitism but it explores the possibility that antisemitism may be an effect even of some antiracist forms of anti- Zionism. -

Department of English and American Studies English Language And

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Gabriela Gogelová The Home Guard and the French Resistance in Situation Comedies by David Croft Bachelor‟s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Stephen Paul Hardy, Ph. D. 2015 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………… Author‟s signature I would like to thank my supervisor, Stephen Paul Hardy, Ph.D., for his professional advice, encouragement and patience. Table of Contents General Introduction 5 Chapter I: Situation Comedy and the BBC 8 Chapter II: Analysis of Dad’s Army 12 Description of the Characters 12 The British Home Guard vs. Croft and Perry‟s Dad’s Army 25 Chapter III: Analysis of ‘Allo ‘Allo! 30 Description of the Characters 30 The French Resistance vs. Croft and Lloyd‟s ‘Allo ‘Allo! 41 Conclusion 46 Works Cited 52 English Resume 55 Czech Resume 56 General Introduction The Second World War was undoubtedly the most terrible conflict of the twentieth century and one of the most destructive wars in history. It may therefore seem surprising that comedy writer David Croft chose exactly this period as a background for his most successful situation comedies. However, the huge success of the series Dad’s Army and ‘Allo ‘Allo! suggests that he managed to create sitcoms that are entertaining for wide audience and not offensive despite their connection to the Second World War. This thesis focuses on two of David Croft‟s sitcoms, Dad’s Army and ‘Allo ‘Allo!. The firstly mentioned sitcom was created in cooperation with Jimmy Perry and ran on BBC1 almost ten years from 1968 to 1977. -

A Companion to Nineteenth- Century Britain

A COMPANION TO NINETEENTH- CENTURY BRITAIN Edited by Chris Williams A Companion to Nineteenth-Century Britain A COMPANION TO NINETEENTH- CENTURY BRITAIN Edited by Chris Williams © 2004 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 108, Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1JF, UK 550 Swanston Street, Carlton South, Melbourne, Victoria 3053, Australia The right of Chris Williams to be identified as the Author of the Editorial Material in this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. First published 2004 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A companion to nineteenth-century Britain / edited by Chris Williams. p. cm. – (Blackwell companions to British history) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-631-22579-X (alk. paper) 1. Great Britain – History – 19th century – Handbooks, manuals, etc. 2. Great Britain – Civilization – 19th century – Handbooks, manuals, etc. I. Williams, Chris, 1963– II. Title. III. Series. DA530.C76 2004 941.081 – dc22 2003021511 A catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library. Set in 10 on 12 pt Galliard by SNP Best-set Typesetter Ltd., Hong Kong Printed and bound in the United Kingdom by TJ International For further information on Blackwell Publishing, visit our website: http://www.blackwellpublishing.com BLACKWELL COMPANIONS TO BRITISH HISTORY Published in association with The Historical Association This series provides sophisticated and authoritative overviews of the scholarship that has shaped our current understanding of British history. -

Churchill Activities B1

Churchill Activities B1 Pre-reading Activities Activity A. 1. Find the odd man out. In each list, circle the name of the person who is different. a. George Washington l Abraham Lincoln l Franklin D. Roosevelt l Jack London l George Bush l Barack Obama b. Benedict Cumberbatch l Emma Watson l Daniel Craig l Daniel Radcliffe l Keira Knightley l Elvis Presley c. Margaret Thatcher l John Lennon l Neville Chamberlain l Tony Blair l Theresa May l David Cameron d. James Dean l Scarlett Johannsson l Denzel Washington l Marilyn Monroe l Beyoncé l Leonardo Di Caprio 2. Choose a title for each list British Kings l American singers l British Prime Ministers l American actors British writers l American Presidents l American poets l British actors. a. ___________________________________________________________________________________ b. ___________________________________________________________________________________ c. ___________________________________________________________________________________ d. ___________________________________________________________________________________ www.speakeasy-news.com - January 2018 B1 Churchill |1| 3. This man is Winston Churchill. Which category from A.2. does he belong to? ___________________________________ 4. Now write a sentence. To choose the tense you have to know if he is dead or alive. To find the information log onto http://www.bbc.co.uk/schools/primaryhistory/famouspeople/winston_churchill a. Which information helped you? ______________________________________________________________ b. So, which -

Review of Sebag-Montefiore, Hugh, Dunkirk: Fight to the Last Man James V

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons Economics Faculty Publications Department of Economics 5-2009 Review of Sebag-Montefiore, Hugh, Dunkirk: Fight to the Last Man James V. Koch Old Dominion University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/economics_facpubs Part of the European History Commons, and the Nonfiction Commons Repository Citation Koch, James V., "Review of Sebag-Montefiore, Hugh, Dunkirk: Fight to the Last Man" (2009). Economics Faculty Publications. 14. https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/economics_facpubs/14 Original Publication Citation Koch, J. V. (2009). Review of Sebag-Montefiore, Hugh, Dunkirk: Fight to the Last Man. H-Net Reviews, 1-3. This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Economics at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Economics Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. H-Net Revie in the Humanities & Social Hugh Sebag-Montefiore. Dunkirk: Fight to the Last Man. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2006. xvii + 701 pp. $35.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-674-02439-7. Reviewed by James V. Koch (Old Dominion University) Published on H-German (May, 2009) Commissioned by Susan R. Boettcher Definitely a Fight, But Not to the Last Man Hugh Sebag-Montefiore correctly notes that multi- Sebag-Montefiore traces how the 338,226 individu- tudes of books already have been written about the evac- als were evacuated from Dunkirk between May 26 and uation of the British and French troops from Dunkirk in June 4, 1940. British ships rescued more than 200,000 ad- May and June 1940. -

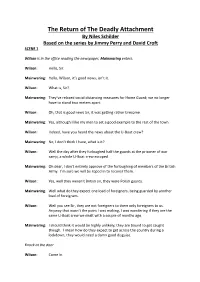

The Return of the Deadly Attachment by Niles Schilder Based on the Series by Jimmy Perry and David Croft SCENE 1

The Return of The Deadly Attachment By Niles Schilder Based on the series by Jimmy Perry and David Croft SCENE 1 Wilson is in the office reading the newspaper, Mainwaring enters. Wilson: Hello, Sir. Mainwaring: Hello, Wilson, it’s good news, isn’t it. Wilson: What is, Sir? Mainwaring: They’ve relaxed social distancing measures for Home Guard; we no longer have to stand two meters apart. Wilson: Oh, that is good news Sir, it was getting rather tiresome. Mainwaring: Yes, although I like my men to set a good example to the rest of the town. Wilson: Indeed, have you heard the news about the U-Boat crew? Mainwaring: No, I don’t think I have, what is it? Wilson: Well the day after they furloughed half the guards at the prisoner of war camp, a whole U-Boat crew escaped. Mainwaring: Oh dear, I don’t entirely approve of the furloughing of members of the British Army. I’m sure we will be roped in to recover them. Wilson: Yes, well they weren’t British sir, they were Polish guards. Mainwaring: Well what do they expect one load of foreigners, being guarded by another load of foreigners. Wilson: Well you see Sir, they are not foreigners to them only foreigners to us. Anyway that wasn’t the point I was making, I was wondering if they are the same U-Boat crew we dealt with a couple of months ago. Mainwaring: I should think it would be highly unlikely; they are bound to get caught though. I mean how do they expect to get across the country during a lockdown, they would need a damn good disguise. -

The Rise of the German Menace

The Rise of the German Menace Imperial Anxiety and British Popular Culture, 1896-1903 Patrick Longson University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Doctoral Thesis for Submission to the School of History and Cultures, University of Birmingham on 18 October 2013. Examined at the University of Birmingham on 3 January 2014 by: Professor John M. MacKenzie Professor Emeritus, University of Lancaster & Professor Matthew Hilton University of Birmingham Contents Introduction 1 Chapter 1 Before the German Menace: Imperial Anxieties up to 1896 25 Chapter 2 The Kruger Telegram Crisis 43 Chapter 3 The Legacy of the Kruger Telegram, 1896-1902 70 Chapter 4 The German Imperial Menace: Popular Discourse and British Policy, 1902-1903 98 Conclusion 126 Bibliography 133 Acknowledgments The writing of this thesis has presented many varied challenges and trials. Without the support of so many people it would not have been possible. My long suffering supervisors Professor Corey Ross and Dr Kim Wagner have always been on hand to advise and inspire me. They have both gone above and beyond their obligations and I must express my sincere thanks and lasting friendship. -

Article the Empire Strikes Back: Brexit, the Irish Peace Process, and The

ARTICLE THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK: BREXIT, THE IRISH PEACE PROCESS, AND THE LIMITATIONS OF LAW Kieran McEvoy, Anna Bryson, & Amanda Kramer* I. INTRODUCTION ..........................................................610 II. BREXIT, EMPIRE NOSTALGIA, AND THE PEACE PROCESS .......................................................................615 III. ANGLO-IRISH RELATIONS AND THE EUROPEAN UNION ...........................................................................624 IV. THE EU AND THE NORTHERN IRELAND PEACE PROCESS .......................................................................633 V. BREXIT, POLITICAL RELATIONSHIPS AND IDENTITY POLITICS IN NORTHERN IRELAND ....637 VI. BREXIT AND THE “MAINSTREAMING” OF IRISH REUNIFICATION .........................................................643 VII. BREXIT, POLITICAL VIOLENCE AND THE GOVERNANCE OF SECURITY ..................................646 VIII. CONCLUSION: BREXIT AND THE LIMITATIONS OF LAW ...............................................................................657 * The Authors are respectively Professor of Law and Transitional Justice, Senior Lecturer and Lecturer in Law, Queens University Belfast. We would like to acknowledge the comments and advice of a number of colleagues including Colin Harvey, Brian Gormally, Daniel Holder, Rory O’Connell, Gordon Anthony, John Morison, and Chris McCrudden. We would like to thank Alina Utrata, Kevin Hearty, Ashleigh McFeeters, and Órlaith McEvoy for their research assistance. As is detailed below, we would also like to thank the Economic -

The Human Relationship with Our Ocean Planet

Commissioned by BLUE PAPER The Human Relationship with Our Ocean Planet LEAD AUTHORS Edward H. Allison, John Kurien and Yoshitaka Ota CONTRIBUTING AUTHORS: Dedi S. Adhuri, J. Maarten Bavinck, Andrés Cisneros-Montemayor, Michael Fabinyi, Svein Jentoft, Sallie Lau, Tabitha Grace Mallory, Ayodeji Olukoju, Ingrid van Putten, Natasha Stacey, Michelle Voyer and Nireka Weeratunge oceanpanel.org About the High Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy The High Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy (Ocean Panel) is a unique initiative by 14 world leaders who are building momentum for a sustainable ocean economy in which effective protection, sustainable production and equitable prosperity go hand in hand. By enhancing humanity’s relationship with the ocean, bridging ocean health and wealth, working with diverse stakeholders and harnessing the latest knowledge, the Ocean Panel aims to facilitate a better, more resilient future for people and the planet. Established in September 2018, the Ocean Panel has been working with government, business, financial institutions, the science community and civil society to catalyse and scale bold, pragmatic solutions across policy, governance, technology and finance to ultimately develop an action agenda for transitioning to a sustainable ocean economy. Co-chaired by Norway and Palau, the Ocean Panel is the only ocean policy body made up of serving world leaders with the authority needed to trigger, amplify and accelerate action worldwide for ocean priorities. The Ocean Panel comprises members from Australia, Canada, Chile, Fiji, Ghana, Indonesia, Jamaica, Japan, Kenya, Mexico, Namibia, Norway, Palau and Portugal and is supported by the UN Secretary-General’s Special Envoy for the Ocean.