Is There a January Effect in the Greater China Area?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Contents the Year 2002 in Review Major Events of Hong Kong

List of Contents The year 2002 in review Major events of Hong Kong securities market 2002 Market highlights Cash market - Main board Cash market - Growth enterprise market (GEM) Derivatives market Clearing statistics Exchange participants The investing community Hong Kong stock market historical events Appendices The Year 2002 in Review The Year The Year 2002 in Review The Hong Kong economy remained weak in 2002 but trade figures began to turn around in the second half of the year. Benefiting from the weakening US dollar and strong demand in the Mainland of China, Hong Kong’s total exports regained double-digit growth over a year earlier in the third quarter of 2002. The seasonally adjusted unemployment rate also fell from its historical peak of 7.8% in July 2002 to 7.2% in December 2002. However, the domestic sector remained sluggish in both investment and consumer spending. The latest economic forecast suggests a 2% growth in real terms of GDP and a 3% decline in the Composite Consumer Price Index for 2002. The trading performance of the Hong Kong securities and futures markets further weakened during the year. Hang Seng Index fell 18.2% from the previous year to end at 9,321.29. The average daily turnover of the Main Board also declined to HK$6,474 million, 19.3% less than that in 2001. The GEM Index ended at 110.4 at end of December 2002, representing a decrease of 44.6% from the previous year. The average daily turnover of the GEM improved slightly to HK$178 million in 2002, an increase of 9.9% from 2001. -

Geely Auto Alert

Deutsche Bank Markets Research Rating Company Date 4 March 2015 Hold Geely Auto Alert Breaking News Asia China Reuters Bloomberg Exchange Ticker Price at 4 Mar 2015 (HKD) 3.31 Automobiles & 0175.HK 175 HK HKG 0175 Price target - 12mth (HKD) 2.95 Components ADR Ticker ISIN 52-week range (HKD) 3.61 - 2.44 GELYY US36847Q1031 HANG SENG INDEX 24,703 Disposal of manual transmission Vincent Ha, CFA Research Analyst business (+852) 2203 6247 To stay focused on core auto manufacturing operation [email protected] Geely announced after today’s market close that the company will sell its manual transmission manufacturing operation to Zhejiang Wanliyang Stock data Transmission (002434.SZ, RMB19.36, Not Rated), an auto part supplier for RMB300m, 1.13x December 2014 NAV. After the completion of the sale, Geely Market cap (HKDm) 29,133 expects to probably realize RMB35m disposal gain, and will procure manual Market cap (USDm) 3,757 transmissions from Wanliyang at least until December 2018. Shares outstanding (m) 8,801.4 Major shareholders Zhejiang Geely According to Geely, the manual transmission business disposal is in line with Hldg (45%) the company’s strategy of streamlining its business to be focused on Free float (%) 57 automobile manufacturing. To recap, Geely also sold its automatic Avg daily value traded 18.8 transmission business back to its parent Zhejiang Geely in FY14 for similar (USDm) reason. Source: Deutsche Bank We do not see a material long-term impact on Geely’s operations or financials Key data from the subject business sale other than for less inter-segmental revenue. -

Hsi Total Return Index Futures Hscei Total Return Index Futures

HSI TOTAL RETURN INDEX FUTURES HSCEI TOTAL RETURN INDEX FUTURES September 2018 INTRODUCTION In stock investing, the return and risk profile for investors has two components: stock price appreciation and dividend. The conventional stock Index futures such as the Hang Seng Index (HSI) futures and Hang Seng China Enterprises Index (HSCEI) futures are risk management tools based on an index calculated from prices of constituent stocks only. The introduction of total return index (TRI) futures by Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited (HKEX) aims to meet the trading and risk management needs of investors who adopt a total return strategy. TRI futures are based on an index calculated by assuming the cash dividends of constituent stocks are re-invested into the index’s portfolio according to their respective market capitalisation weightings. The Hong Kong Futures Exchange Limited (HKFE) is offering four TRI futures contracts: • Hang Seng Index (Gross Total Return Index) Futures (HSIGTRI Futures) • Hang Seng Index (Net Total Return Index) Futures (HSINTRI Futures) • Hang Seng China Enterprises Index (Gross Total Return Index) Futures (HSCEIGTRI Futures) • Hang Seng China Enterprises Index (Net Total Return Index) Futures (HSCEINTRI Futures) USAGES OF TRIS Due to the unique nature of indexing, TRIs are widely used by fund managers, actuaries and financial advisers to measure their index-based performances in equity funds and pension funds, as price indexes fail to capture the dividend income of the equity funds over time. TRIs are commonly used as the underlying index of equity total return index swaps traded in the over-the-counter (OTC) market among banks, insurance companies and investment funds, which enable users to realise the economic benefits of ownership of shares – price appreciation and dividend return – without the cost of capital outlay and expense of the consequences of ownership, such as custodian arrangements and regular reconciliations. -

CSOP Hang Seng Index Daily (-1X) Inverse Product

Evaluation Only. Created with Aspose.PDF. Copyright 2002-2019 Aspose Pty Ltd. CSOP Hang Seng Index Daily (-1x) Inverse Product Stock Code : 7300 HK All Information as of 30 July 2021 IMPORTANT: Investments involve risks, including the total loss of your investment. Investors are advised to consider their own investment objectives and circumstances in determining the suitability of an investment in the CSOP Hang Seng Index Daily (-1x) Inverse Product (the “Product”). CSOP Hang Seng Index Daily (-1x) Inverse Product is a futures-based product which invests directly in futures contracts on the Hang Seng Index (“HSI Futures”) listed on the HKFE so as to give the Product the inverse (-1x) of the daily performance of the Hang Seng Index ("Index") This is an inverse product and is different from conventional ETF. Should the value of the underlying securities of the Index increase, it could have a negative effect on the performance of the Product. Unitholders could, in certain circumstances including a bull market, face minimal or no returns, or may even suffer a complete loss, on such investments. The Product is designed to be used for short term trading or hedging purposes, and is not intended for long term investment. The Product is not intended for holding longer than one day as the performance of this Product over a longer period may deviate from and be uncorrelated to the inverse performance of the Index over the period. Investment in futures contracts involves specific risks such as high volatility, leverage, rollover and margin risks. A relatively small price movement in HSI Futures may result in a proportionally high impact and substantial losses to the Product, having a material adverse effect on the NAV. -

Support at 100 Day SMA; Regulatory Concerns Remained on Other Digital Platform Leaders

Investment Daily 13 April 2021 Major Market Indicators Market Overview 12 Apr 9 Apr 8 Apr Mkt. Turn.(mn) 160,700 141,700 281,100 Support at 100 Day SMA; Regulatory Concerns Remained on other Stock Advances 534 637 943 digital platform leaders Stock Declines 1,155 1,025 742 Hang Seng index opened up 93 points. However, due to tightening regulatory concern, HSI 28,453 28,699 29,008 Hang Seng index gradually retreated in the morning and stabilized in the afternoon, closing Change -246 -309 +333 at 28,453, down 245 points. H-shares index fell 102 points to 10,874, and Hang Seng Tech HSI Turn.($bn) 74.51 53.46 194.82 index declined 136 points to 8,169. Market turnover amounted to HK$160.7bn. AAC Tech HSCEI 10,875 10,977 11,109 (2018) issued a positive profit alert at the lunch break, triggering share price up 12.7%. Change -103 -132 +39 China’s regulator fined Rmb18.2bn on Alibaba (9988) due to its monopoly acts, but its HSCEI Turn.($bn) 75.21 54.29 193.04 share price rebounded 6.5% on lower-than-expected penalties. Geely (0175) was reported to involve in a consumption probe, with its share price down 7%, being the worst-performing blue-chip stock. HSI Technical Indicators Ahead of the major US enterprises announce the first quarter result, US stock market traded 10-days MA 28,530 50-days MA 29,204 within narrow range on Monday. The three major US index closed slightly lower with the 250-days MA 26,030 Nasdaq index fell 0.4% which performed the worst. -

Fund Information

Fund Information HANG SENG INDEX FUND CLASS A (HKD) (MIP) (U42281) Fund Price Type of Morningstar Fund Size Risk Level Investment Tenor Divdend Policy Change vs Previous Investment Return Overall Rating NAV Last Update Trading Day (%) HKD28.94000 0.07% 27-09-2021 (PM) HKD 2,501,252,407.00 4 ≥1 Year(s) Inc (Unit) 3 ★★ 0 Month(s) Product Features - Investment Objective and Strategy The investment objective of the Fund is to match as closely as practicable, before fees and expenses, the total return performance (net of withholding tax) of the Hang Seng Index (the “Index”) through investing primarily in the constituent stocks of the Index. The Manager primarily adopts the full replication strategy by which the assets of the Fund comprise the constituent stocks with reference to their respective weightings in the Index or futures contracts on the Index. Exposure to the Index may also be obtained through other index-tracking strategies or financial derivative instruments (such as futures contracts) from which the return to the Fund will substantially reflect the performance of the Index. The Fund's net derivative exposure may be up to 50% of its Net Asset Value. Fund Portfolio as of 30-06-2021 Asset Allocation Equity Holdings Geographical Allocation Equity Holdings Sector Allocation Stock Bond Cash Other 99.07 0.00 0.93 0.00 Total Number of Equity Holdings 58 Total Number of Bond Holdings 0 Fee Information Performance History Subscription Fee 3.00% Switching Handling Fee 1% *Not applicable to Guaranteed Funds* Management Fee 1.000% p.a. Redemption Fee - Performance Fee - Incentive Fee - Other Fund Information Launch Date 13-07-1998 Fund Type Index Fund and Index Leveraged Fund Fund Category Greater China Equity Investment Market Sector Hong Kong Equity Dealing Freqeuncy/ Dealing Cut-off Time Two Dealing Sessions per Dealing Day / Fund indexed performance (initial value =100%). -

Geely Auto Alert

Deutsche Bank Markets Research Rating Company Date 28 March 2016 Hold Geely Auto Alert Company Update Asia China Reuters Bloomberg Exchange Ticker Price at 24 Mar 2016 (HKD) 3.70 Automobiles & 0175.HK 175 HK HSI 0175 Price target - 12mth (HKD) 3.70 Components ADR Ticker ISIN 52-week range (HKD) 4.67 - 2.51 GELYY US36847Q1031 HANG SENG INDEX 20,346 Boyue SUV launch reverse roadshow Vincent Ha, CFA ta keaways Research Analyst Geely hosted a reverse roadshow on 27 March, right after the launch of Boyue (+852 ) 2203 6247 SUV on the 26th. Key takeaways are as below: [email protected] - 1Q16E sales review: Geely recorded muted YoY sales growth in 1Q16, and management attributed that to 1) high base effect, 2) lack of new models and Stock data some models' discontinuation, and 3) inventory destocking. Indeed, the Market cap (HKDm) 32,567 company expects March retail sales to grow 20% YoY, better than wholesale Market cap (USDm) 4,198 growth. - Company outlook: Management believes that FY16E is going to be a turning Shares outstanding (m) 8,802.0 point as they expect the Borui mid-size sedan facelift (to be launched in April) Major shareholders Zhejiang Geely and the just-launched Boyue (with a competitive price range of RMB98.8k- Hldg (45%) 157.8k) to boost its sales in 2Q-4Q16E. Geely is therefore comfortable with its Free float (%) 56 600k-unit 2016E sales target. Avg daily value traded 28.7 - Boyue: the pre-order of Boyue has already reached about 15k-16k units. (USDm) Management expects the model's margin to be higher than Borui, which Source: Deutsche Bank shares the same platform. -

BVMF Hang Seng Index Futures Contract with Cash Settlement Denominated in Points of the Hang Seng Index of Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited

BVMF Hang Seng Index Futures Contract with cash settlement denominated in Points of the Hang Seng Index of Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited – Specifications – 1. Definitions BVMF Hang Seng BVMF Hang Seng Index Futures Contract, based on the Index Futures Contract Hang Seng Index traded on Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited, located in Hong Kong, China, hereafter named HKEx. Daily settlement price (PA): The daily closing price, expressed in index points, calculated and/or arbitrated daily by BM&FBOVESPA, at its own discretion, for each contract month, for the purpose of updating the value of open positions and for calculating the daily adjustment and settlement value. Settlement Price (P): The closing price with the objective of settling open positions calculated and/or arbitrated by BM&FBOVESPA, at its own discretion, for each contract month, and expressed by the price of the Hang Seng Index, which is published by HKEx on the expiration date of the contract. Business day: For the purposes of this contract, for cash settlement and to meet the margin call, any day that is a trading day at BM&FBOVESPA. BM&FBOVESPA or Exchange BM&FBOVESPA S.A. – Bolsa de Valores, Mercadorias e Futuros. 2. Underlying asset Hang Seng Index. 3. Price quotation Points of the BVMF Hang Seng Index Futures Contract. 4. Minimum price fluctuation One (1) index point. 5. Contract size The BVMF Hang Seng Index Futures Contract, times the value of the point established by the Exchange, with each point having the value of sixty five Brazilian Real cents (BRL 0.65). -

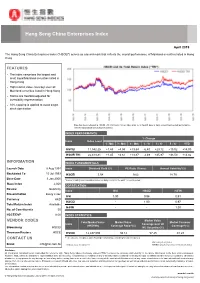

Hang Seng China Enterprises Index

Hang Seng China Enterprises Index April 2019 The Hang Seng China Enterprises Index ("HSCEI") serves as a benchmark that reflects the overall performance of Mainland securities listed in Hong Kong. FEATURES ■ The index comprises the largest and most liquid Mainland securities listed in Hong Kong ■ High market value coverage over all Mainland securities listed in Hong Kong ■ Stocks are freefloat-adjusted for investibility representation ■ 10% capping is applied to avoid single stock domination Data has been rebased at 100.00. All information for an index prior to its launch date is back-tested, back-tested performance reflects hypothetical historical performance. INDEX PERFORMANCE % Change Index Index Level 1 - Mth 3 - Mth 6 - Mth 1 - Yr 3 - Yr 5 - Yr YTD HSCEI 11,542.25 +1.43 +4.59 +13.84 -6.40 +29.12 +18.02 +14.00 HSCEI TRI 22,413.81 +1.45 +4.61 +13.87 -2.49 +45.97 +43.50 +14.02 INFORMATION INDEX FUNDAMENTALS Launch Date 8 Aug 1994 Index Dividend Yield (%) PE Ratio (Times) Annual Volatility*(%) Backdated To 15 Jul 1993 HSCEI 3.54 9.62 18.75 Base Date 3 Jan 2000 *Annual Volatility was calculated based on daily return for the past 12-month period. Base Index 2,000 CORRELATION Review Quarterly Index HSI HSCEI H-FIN Dissemination Every 2 sec HSI 1.00 0.96 0.91 Currency HKD HSCEI - 1.00 0.97 Total Return Index Available H-FIN - - 1.00 No. of Constituents 50 HSCEIDVP 0.00 INDEX STATISTICS VENDOR CODES Market Value Total Market Value Market Value Market Turnover Index Coverage over all (HKD Mn) Coverage Ratio^(%) Coverage^(%) Bloomberg HSCEI ML Securities(%) Thomson Reuters .HSCE HSCEI 12,437,096 36.12 57.25 41.28 CONTACT US ^ The universe comprises Main Board primary listings excluding foreign companies HSI: Hang Seng Index Email [email protected] All data as at 30 Apr 2019 H-FIN: Hang Seng China H-Financials Index Disclaimer All information contained herein is provided for reference only. -

Tencent Is to Become a Constituent of Hong Kong's Hang Seng Index

For Immediate Release Tencent is to become a Constituent of Hong Kong’s Hang Seng Index Shenzhen, May 12, 2006 – Tencent Holdings Limited (“Tencent” or the “Company”, SEHK 0700), a leading provider of Internet and mobile & telecommunications value-added services in China, is to become one of the 43 constituents of Hong Kong’s Hang Seng Index on June 10, 2008. Chairman and CEO of Tencent, Mr. Ma Huateng said, “We are extremely pleased with the news, and feel encouraged by the recognition from the market and the Hang Seng Index Company.” Tencent was the first Chinese Internet company to list on the Main Board of the Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited on June 16, 2004. In September 2004, Tencent became a composite stock in the Hang Seng Mainland China Index, IT Industry Index of Hang Seng Composite Industry Indexes and Hang Seng Mainland Freefloat Index. In May 2007, Tencent was included as a composite stock in the MSCI World Index for Hong Kong index. # # # About Tencent Tencent aims to enrich the interactive online experience of Internet users in China by providing a comprehensive range of Internet and wireless value-added services. Through its various online platforms, including Instant Messaging QQ, web portal QQ.com, QQ Game portal, multi-media blog service Qzone and wireless portal, Tencent services the largest online community in China and fulfills the user’s needs for communication, information, entertainment and e-Commerce on the Internet. Tencent currently operates three principal lines of business: Internet value-added services, mobile and telecommunications value-added services and online advertising. -

Issue of USD 1,010,000 Index-Linked Notes Due October 2021 Linked to the HANG SENG CHINA ENT INDX

PRICING SUPPLEMENT Pricing Supplement dated 14 October 2018 HSBC Bank plc Programme for the Issuance of Notes and Warrants Issue of USD 1,010,000 Index-Linked Notes due October 2021 linked to The HANG SENG CHINA ENT INDX PART A - CONTRACTUAL TERMS This document constitutes the pricing supplement (the "Pricing Supplement") relating to the issue of the Tranche of Notes described herein and must be read in conjunction with the offering memorandum dated 6 June 2018 as supplemented from time to time (the "Offering Memorandum"). Terms used herein shall be deemed to be defined as such for the purposes of the terms and conditions of the Notes, including the Terms and Conditions of the Equity Linked Notes and Index Linked Notes (the "Conditions") set forth in the Offering Memorandum. Full information on the Issuer and the offer of the Notes is only available on the basis of the combination of this Pricing Supplement and the Offering Memorandum. The Offering Memorandum is available for viewing at HSBC Bank plc, 8 Canada Square, London E14 5HQ United Kingdom and www.hsbc.com (please follow the links to 'Investor relations', 'Fixed income investors, 'Issuance programmes') and copies may be obtained from HSBC Bank plc, 8 Canada Square, London E14 5HQ United Kingdom. The Offering Memorandum does not comprise (i) a prospectus for the purposes of Part VI of the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (as amended) or (ii) a base prospectus for the purposes of Directive 2003/71/EC as amended (the "Prospectus Directive"). The Offering Memorandum has been prepared solely with regard to Notes that are not to be admitted to listing or trading on any regulated market for the purposes of Directive 2014/65/EU, as amended and not to be offered to the public in a Member State (other than pursuant to one or more of the exemptions set out in Article 3.2 of the Prospectus Directive). -

A STUDY of CORPORATE TAX PLANNING ACTIVITIES in HONG KONG by KO }{Wok-WAI & WONG MAN-FAI MBA PROJECT REPORT Presented To

A STUDY OF CORPORATE TAX PLANNING ACTIVITIES IN HONG KONG by KO }{wOK-WAI & WONG MAN-FAI MBA PROJECT REPORT Presented to The Graduate School In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION THREE-YEAR MBA PROGRAMME THE CHINESE UNIVERSITY OF HONG KONG May 1992 Advisor C) 348215 ii ABSTRACT The purpose of this report is to provide a review of corporation tax planning activities in Hong Kong, including the general environment affecting the attitudes and the potential future orientation. Based on the comments of tax consultants in the Honq Konq tax field, six major key tax planninq techniques are identified. i.e'. (1) sourcing the profit of Honq Konq Company offshore; (2) structurinq receipts to be of capital nature; (3) increasinq allowable deductions; (4) deferrinq payment of tax; (5) diversion and extraction of income; (6) treaty shopping. A review of the tax authority's policy towards tax planning reveals the following philosophies and characteristics: (1) limited anti-avoidance legislation; (2) simple tax system; (3) to preserve the existing simple taxation system. The tax authorities will only interfere and eliminate specific tax-avoidance schemes when these schemes have attracted public attention which creates pressure to the tax authorities to close the loopholes immediately. However, corporate management's attitude towards tax ' planning activi ties is changing throughout the last two iii decades from a passive to an active role following the development of the tax advisory professional during the period. An analysis over the tax pattern of the thirty-three Hang Seng Index consti tution stocks was carried out wi th an objective to identify those major tax planning players and their normal practice to support our previous findings.