Rural Gambian Households - ILCUF June 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gambia Parliamentary Elections, 6 April 2017

EUROPEAN UNION ELECTION OBSERVATION MISSION FINAL REPORT The GAMBIA National Assembly Elections 6 April 2017 European Union Election Observation Missions are independent from the European Union institutions.The information and views set out in this report are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Neither the European Union institutions and bodies nor any person acting on their behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained therein. EU Election Observation Mission to The Gambia 2017 Final Report National Assembly Elections – 6 April 2017 Page 1 of 68 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS .................................................................................................................................. 3 I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................................... 4 II. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................ 9 III. POLITICAL BACKGROUND .................................................................................................................. 9 IV. LEGAL FRAMEWORK AND ELECTORAL SYSTEM ................................................................................. 11 A. Universal and Regional Principles and Commitments ............................................................................. 11 B. Electoral Legislation ............................................................................................................................... -

TEKKI FII GRANT FLYER.Cdr

ACCESS TO FINANCE MINI GRANT. ABOUT THE TEKKI FII MINI-GRANT Powered by YEP, GIZ and IMVF Grants up to D50,000 to facilitate acquisition Grants are disbursed either as cash or as No collateral, interest rate or of equipment, materials, licenses and other assets, but asset disbursements will be repayment requirements. business critical inputs and assets. given priority where feasible. Grantees receive financial literacy training to improve their Grantees participate in annual experience sharing events to capacity to save, exercise financial planning and separate their communicate results, success stories and best practices of the private funds from the funds of the business. mini-grant scheme. ELIGIBILITY CRITERIA Must be a Gambian youth between Must provide a solid business plan Must have some level of savings or commit 18 -35 years using the application form to making regular savings in a financial template. service provider of his or her choice. Must have received entrepreneurship Must provide a guarantor before funds are disbursed to indicate that the grant will be or vocational training. Proof of used for the intended purpose. Failure of doing so implies that the amount of the grant attendance is required. will be refunded in full by the guarantor. Business must be registered by Business plan that shows high level of the time funds are disbursed. innovation will be an advantage. How To Apply? pplication forms are available online on the www.naccug.com | www.tekkifii.gm ou can find it here: www.yep.gm/opportunity/minigrantscheme orms should be filled electronically, printed, signed, scanned and sent by email to [email protected]. -

Dangerous to Dissent Human Rights Under Threat in Gambia

DANGEROUS TO DISSENT HUMAN RIGHTS UNDER THREAT IN GAMBIA Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2016 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover illustration: Solo Sandeng, UDP National Organizing Secretary, taking part in a protest organized (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. by UDP and youth activists to demand electoral reforms in Gambia, April 2016. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode © Amnesty International For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2016 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: AFR 27/4138/2016 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS GLOSSARY 5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 7 METHODOLOGY 10 1. BACKGROUND: THE ROAD TO DECEMBER 2016 11 Long History of Human Rights Violations 11 Human Rights at Risk Before and During the 2016 -18 Election Periods 12 Reforms to the Electoral System 13 2. ATTACKS ON FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION AND MEDIA FREEDOM 15 Weakened and Censored Media 15 Repressive Legal Framework 18 Harassment of Journalists 19 Challenges for International Media Coverage 20 Journalists Fleeing into Exile 21 3. -

The Gambia 2013 Population and Housing Census Preliminary Results

REPUBLIC OF THE GAMBIA The Gambia 2013 Population and Housing Census Preliminary Results Count! Everyone Everywhere in The Gambia Every House Everywhere in The Gambia 2013 Population and Housing Census Preliminary Results Page i The Gambia 2013 Population and Housing Census Preliminary Results The Gambia Bureau of Statistics Kanifing Institutional Layout P.O. Box 3504, Serrekunda Tel: +220 4377-847 Fax: +220 4377-848 email: [email protected] Website: www.gbos.gov.gm Population and Housing Census Preliminary Results Page i ADMINISTRATIVE MAP OF THE GAMBIA Population and Housing Census Preliminary Results Page ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Content Page ADMINISTRATIVE MAP OF THE GAMBIA ………………………………………………………………. ii LIST OF TABLES …………………………………………………………………………………………………….. iv LIST OF FIGURES ………………………………………………………………………………………………….. iv MAP…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. iv FOREWORD …………………………………………………………………………………………………………. v ACKNOWLEDGMENT ………………………………………………………… ……………………………….. vi LIST OF ACRONYMS …………………………………………………………………………………………….. vii 1. BACKGROUND …………………………………………………………………………………………………. 1 1.1 Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 1 1.2 Legal and Administrative Backing of the Census ……………………………………………. 1 1.3 Census Preparatory Activities ………………………………………………………………………… 2 1.4 Decentralization of the Census Activities ………………………………………………………. 4 2. Preliminary Results …………………………………………………………………………………………. 6 2.1 Population Size …………………………………………………………………………………………….. 6 2.2 Population Growth ………………………………………………………………………………………. 6 2.3 Percentage -

Monthly Mobile Qos Report

December 2016 MONTHLY MOBILE QOS REPORT Comparative Quality of Service Report for Mobile Networks Technical Report August 2017 1 May 2017 Contents 1. Glossary of Terms .............................................................................................................................. 4 2. Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) ............................................................................................. 4 3. KPIs & Threshold Used in Report ................................................................................................. 6 4. Findings 1: 2G Networks................................................................................................................. 7 5. Findings 2: Graphs .......................................................................................................................... 11 6. Findings 3: CELL Outages ............................................................................................................. 13 7. Findings 4: Percentage Change in Traffic ................................................................................ 13 7.1. Voice Traffic ................................................................................................................................. 13 7.2. Data Traffic ................................................................................................................................... 14 8. Number of Cells Deployed ............................................................................................................ -

Tekki Fii AGRO-GRANT Flyer

ACCESS TO FINANCE AGRO-GRANT. ABOUT THE TEKKI FII AGRO-GRANT Powered by IMVF Grants of up to D250,000 available for the scaling up of Agro-Enterprises in the NBR and CRR regions. Awarding of the grants will be based on a competitive selection procedure. Grants will target an individual or association/kafo already engaged in Agribusiness. The pre-identified priority sectors are: Agricultural production Livestock production Agro-Processing Aquaculture Bee Keeping Distribution and marketing of agricultural products or inputs. This will be done by facilitating No interest rate or Grantees will receive financial literacy training the in-kind acquisition of repayment requirements. to improve their capacity to save, exercise equipment, materials, licenses financial planning and separate their private and other critical inputs or assets. funds from the funds of the business. Grantees will participate in annual experience sharing events to communicate results, success stories and best practices. ELIGIBILITY CRITERIA Beneficiaries must be Gambian Must be a registered business located in NBR or CRR with proof of business transaction youth 18-35 years. and additional evidence of scalability and potential for job creation The individual or association must The individual should have the Should have some level of savings or commit already be engaged in Agribusiness necessary experience in to making regular savings in a financial within the project intervention area. implementing the selected activity. service provider of his or her choice Must provide a business plan using Agree to maintain in a professional Must provide proof of attendance or the template developed by the manner the recording of the business certificate that they have received Grant Coordinating committee and be open to monitoring. -

STRATEGIC RESPONSE PLAN the Gambia

2014-2016 STRATEGIC RESPONSE PLAN The Gambia January 2014 Prepared by the Humanitarian Country Team in The Gambia SUMMARY PERIOD: January 2014 – December 2014 Strategic objectives 1. Track and analyse risk and vulnerability, integrating findings into 100% humanitarian and development programming. 1.9 million 2. Support vulnerable populations to better cope with shocks by Total population responding earlier to warning signals, by reducing post-crisis recovery times and by building capacity of national actors. 3. Deliver coordinated and integrated life-saving assistance to people 19.5% of total population affected by emergencies. 370,454 Priority actions estimated number of people in need of humanitarian aid • Provide food assistance, nutritional support and agricultural inputs. 9.6% of total population • Restore water systems and access to sanitation facilities in communities, schools and nutrition facilities. 183,160 • Re-establish and provide access to public health/clinical services with people targeted for humanitarian a focus on surveillance and early warning for diseases with epidemic aid in this plan potential. Key categories of people in need: • Improve access to education through creation of temporary learning spaces and strengthening national protection capacity (including Food insecure 285,000 prevention of gender-based violence and child protection). Malnourished • children including Strengthening early warning systems through training of personnel, 48,627 SAM 7,859 and data collection and processing and dissemination of results/findings. MAM 40,768 Parameters of the response 28,502 Pregnant and Lactating Mothers The precise number of people in crisis in The Gambia has not been Refugees comprehensively assessed due to scanty information available. However, 8,325 it is estimated that at least 370,454 people are in need of either immediate humanitarian assistance or remain vulnerable and require some sort of support to strengthen their resilience to future crises. -

Plan of Operation for Field Testing of FMPRG

Gambian Forest Management Concept (GFMC) 2nd Version Draft May 2001 Compiled by Werner Schindele for Department of State for Fisheries, Natural Resources and the Environment Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ) GmbH DFS Deutsche Forstservice GmbH II List of Abbreviations AC Administrative Circle AOP Annual Plan of Operations B.Sc. Bachelor of Science CCSF Community Controlled State Forest CF Community Forestry CFMA Community Forest Management Agreement CRD Central River Division DCC Divisional Coordinating Committee DFO Divisional Forest Officer EIS Environmental Information System FD Forestry Department FP Forest Parks GFMC Gambian Forestry Management Concept GGFP Gambian-German Forestry Project GOTG Government of The Gambia IA Implementation Area JFPM Joint Forest Park Management LRD Lower River Division MDFT Multi-disciplinary Facilitation Teams M&E Monitoring and Evaluation NAP National Action Programme to Combat Desertification NBD North Bank Division NEA National Environment Agency GEAP Gambia Environmental Action Plan NFF National Forest Fund NGO Non Government Organization PA Protected Areas PCFMA Preliminary Community Forest Management Agreement R&D Research and Development URD Upper River Division WD Western Division III Table of Contents List of Abbreviations Foreword Introduction 1 The Nucleus Concept of the GFMC 4 1.1 Status of GFMC and Relation to other Plans 4 1.2 Long-term Vision 4 1.3 Objectives, Principles and Approach 5 1.3.1 Objectives 5 1.3.2 Principles 5 1.3.3 Approach 6 1.4 Forest Status and -

Historical Dictionary of the Gambia

HDGambiaOFFLITH.qxd 8/7/08 11:32 AM Page 1 AFRICA HISTORY HISTORICAL DICTIONARIES OF AFRICA, NO. 109 HUGHES & FOURTH EDITION PERFECT The Gambia achieved independence from Great Britain on 18 February 1965. Despite its small size and population, it was able to establish itself as a func- tioning parliamentary democracy, a status it retained for nearly 30 years. The Gambia thus avoided the common fate of other African countries, which soon fell under authoritarian single-party rule or experienced military coups. In addi- tion, its enviable political stability, together with modest economic success, enabled it to avoid remaining under British domination or being absorbed by its larger French-speaking neighbor, Senegal. It was also able to defeat an attempted coup d’état in July 1981, but, ironically, when other African states were returning to democratic government, Gambian democracy finally suc- Historical Dictionary of Dictionary Historical cumbed to a military coup on 22 July 1994. Since then, the democracy has not been restored, nor has the military successor government been able to meet the country’s economic and social needs. THE This fourth edition of Historical Dictionary of The Gambia—through its chronology, introductory essay, appendixes, map, bibliography, and hundreds FOURTH EDITION FOURTH of cross-referenced dictionary entries on important people, places, events, institutions, and significant political, economic, social, and cultural aspects— GAMBIA provides an important reference on this burgeoning African country. ARNOLD HUGHES is professor emeritus of African politics and former direc- tor of the Centre of West African Studies at the University of Birmingham, England. He is a leading authority on the political history of The Gambia, vis- iting the country more than 20 times since 1972 and authoring several books and numerous articles on Gambian politics. -

Gambian Mixed Farming and Project

Mied Farming fin " -- / Technical Report RANGE RESOURCE INVENTORY by Scotty Deffendol, Edward Riegelman Lauren LeCroy Alieu Joof Omar Njai Technical Report No. 17 July 1986 GAMBIAN MIXED FARMING AND RESOURCE. MANAGEMENT PROJECT Ministry of Agriculture and Natural Rcsou, ces Government of The Gambia Consortium for !hternational Developmernt Colcrado State University RANGE RESOURCE INVENTORY by Scotty Deffendol Edward Riegelman Lauren LeCroy Alieu Joof Omar Njai Prepared with support of the United States Agency for International Development. All expressed opinions, conclusi;ons and recommendations are those of the authors and not cf the funding agency, the United States Government or the Government of The Gambia. MIXED FARMING PROJECT July 1986 FINL~t REPORT' bW6E EC'OLOSY CWUN!ET MIXED FAItIe PROJECT PART 1I - WE RESOURCE INVENTORY - A SUMMARY INTRODUCTION4 The basic tool inplanning range management programs isknowing what grazing resources are available, inwhat quality and quantity, and where they are located inrelationship to each other and to other physical resources, such as human habitats, farm lands, stock 4ater, forests, and roads. This type of information has not been available. This portion of the final report deals with The Range Resource Invtntorl conducted exclusively in MacCarthy Island and Upper River Diuisicis, the two most eastern Divisions inThe Gambia, representing sme 494,000 hectares of land mass. (Appendix 3) Included isa series of nineteen maps at a scale of 1:25,000. The nineteen Maps are indispensablo, and are meant to accompany this report, but because of size and numbers their inclusion may be iripossible. A permanent copy will be with the Range Unit of the Department of Animal health and Production, Abuko. -

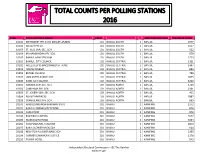

Total Counts Per Polling Stations 2016

TOTAL COUNTS PER POLLING STATIONS 2016 Code Name of Polling Station Count Administrative Area Registered voters 10101 METHODIST PRI. SCH.( WESLEY ANNEX) 101 BANJUL SOUTH 1 BANJUL 1577 10102 WESLEY PRI.CH. 101 BANJUL SOUTH 1 BANJUL 1557 10103 ST. AUG. JNR. SEC. SCH. 101 BANJUL SOUTH 1 BANJUL 522 10104 MUHAMMADAN PRI. SCH. 101 BANJUL SOUTH 1 BANJUL 879 10105 BANJUL MINI STADIUM 101 BANJUL SOUTH 1 BANJUL 1723 10201 BANJUL. CITY COUNCIL 102 BANJUL CENTRAL 1 BANJUL 1151 10202 WELLESLEY & MACDONALD ST. JUNC. 102 BANJUL CENTRAL 1 BANJUL 1497 10203 ODEON CINEMA 102 BANJUL CENTRAL 1 BANJUL 889 10204 BETHEL CHURCH 102 BANJUL CENTRAL 1 BANJUL 799 10205 LANCASTER ARABIC SCH. 102 BANJUL CENTRAL 1 BANJUL 1835 10206 22ND JULY SQUARE . 102 BANJUL CENTRAL 1 BANJUL 3200 10301 GAMBIA SEN. SEC. SCH. 103 BANJUL NORTH 1 BANJUL 1730 10302 CAMPAMA PRI. SCH. 103 BANJUL NORTH 1 BANJUL 2361 10303 ST. JOSEPH SEN. SEC. SCH. 103 BANJUL NORTH 1 BANJUL 455 10304 POLICE BARRACKS 103 BANJUL NORTH 1 BANJUL 1887 10305 CRAB ISLAND JUN. SCH. 103 BANJUL NORTH 1 BANJUL 669 20101 WASULUNKUNDA BANTANG KOTO 201 BAKAU 2 KANIFING 2272 20102 BAKAU COMMUNITY CENTRE 201 BAKAU 2 KANIFING 878 20103 CAPE POINT 201 BAKAU 2 KANIFING 878 20104 KACHIKALI CINEMA 201 BAKAU 2 KANIFING 1677 20105 MAMA KOTO ROAD 201 BAKAU 2 KANIFING 3064 20106 INDEPENDENCE STADIUM 201 BAKAU 2 KANIFING 2854 20107 BAKAU LOWER BASIC SCH 201 BAKAU 2 KANIFING 614 20108 NEW TOWN LOWER BASIC SCH. 201 BAKAU 2 KANIFING 2190 20109 FORMER GAMWORKS OFFICE 201 BAKAU 2 KANIFING 2178 20110 FAJARA HOTEL 201 BAKAU 2 KANIFING 543 Independent Electoral Commission – IEC The Gambia www.iec.gm 20201 EBO TOWN MOSQUE 202 JESHWANG 2 KANIFING 5056 20202 KANIFING ESTATE COMM. -

Education Sector Analysis Methodological Guidelines

EDUCATION SECTOR ANALYSIS METHODOLOGICAL GUIDELINES VOLUME 1 International Institute for Educational Planning Layout : by Reg’ - www.designbyreg.dphoto.com ISBN: 978-92-806-4715-0 September, 2014 Nota bene The ideas and opinions expressed in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of UNESCO, UNICEF, the World Bank or the Global Partnership for Education. The designations used in this publication and the presentation of data do not imply that UNESCO, UNICEF, the World Bank or the Global Partnership for Education have adopted any particular position with respect to the legal status of the countries, territories, towns or areas, their governing bodies or their frontiers or boundaries. EDUCATION SECTOR ANALYSIS METHODOLOGICAL GUIDELINES SECTOR-WIDE ANALYSIS, WITH EMPHASIS ON PRIMARY AND SECONDARY EDUCATION VOLUME 1 International Institute for Educational Planning With the financial support of: Table of Contents 2 List of Examples 6 List of Tables 10 List of Figures and Maps 14 List of Boxes 16 Foreword 18 Acknowledgements 20 Acronyms and Abbreviations 22 Introduction 27 CHAPTER 1 33 CONTEXT OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE EDUCATION SECTOR Introduction 36 SECTION 1: THE SOCIAL, HUMANITARIAN AND DEMOGRAPHIC CONTEXTS 37 1.1 The Evolution of the Total Population and the School-Aged Population 38 1.2 Basic Social Indicators 42 1.3 Impact of HIV/AIDS and Malaria on Education 45 1.4 The Composite Social Context Index 48 1.5 Linguistic Context 49 1.6 Humanitarian context 50 SECTION 2: THE MACROECONOMIC AND PUBLIC