The Impact of Aviation Reforms in the Dominican Republic: a Model of Socioeconomic Growth and Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table 01 Visitor Arrivals to Jamaica 2001 to 2015.Xlsx

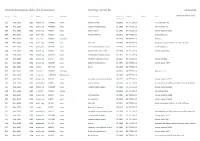

TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE NO. PAGE Definitions iv Introduction v - vi An Overview of 2015 vii - xxviii Summary of Main Indicators 1 1 Visitor Arrivals to Jamaica 2001 - 2015 2 2 Total Stopover Arrivals by Month 2011 - 2015 3 3 Total Stopover Arrivals by Port of Arrival 2013 & 2015 4 4 Stopover Arrivals by Country and Month of Arrival 2015 - U.S.A. Northeast and Mid-West 6 - 7 - U.S.A. South and West 8 - 9 - Canada and Europe 10 - 11 - Latin America 12 - 13 - Caribbean, Asia and Other Countries 14 - 15 5 Stopover Arrivals by Country of Residence and Year 2011 - 2015 - U.S.A. Northeast and Mid-West 18 - U.S.A. South and West 19 - Canada and Europe 20 - Latin America 21 - Caribbean, Asia and Other Countries 22 6a Stopover Arrivals by Main Producing States 2015 & 2014 25 6b Stopover Arrivals by Main Producing Provinces 2015 & 2014 26 6c Stopover Arrivals by Main Producing European Countries 2015 & 2014 28 6d Stopover Arrivals by Main Producing Caribbean Countries 2015 & 2014 30 6e Stopover Arrivals by Main Producing Latin American Countries 2015 & 2014 32 7 Age Distribution of Stopover Arrivals 2014 & 2015 34 8 Gender Distribution of Stopover Arrivals 2014 & 2015 35 8.1 Stopover Arrivals by Purpose of Visit 2012 - 2015 36 8.1a Main Purpose of Visit by Main Markets 2015 36 8.2 Stopover Arrivals by Intended Resort Area of Stay 2013 - 2015 37 8.2a Stopover Arrivals by Main Market and Intended Resort Area of Stay 2015 37 9 Average Length of Stay (Nights) by Month and Year (Foreign Nationals) 2011 - 2015 38 9a Average Length of Stay (Nights) by Country and Year (Foreign Nationals) 2011 - 2015 39 9.1 Average Length of Stay (Nights) by Month and Year Non-Resident Jamaicans 2011 – 2015 40 i TABLE NO. -

U.S. Department of Transportation Federal

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF ORDER TRANSPORTATION JO 7340.2E FEDERAL AVIATION Effective Date: ADMINISTRATION July 24, 2014 Air Traffic Organization Policy Subject: Contractions Includes Change 1 dated 11/13/14 https://www.faa.gov/air_traffic/publications/atpubs/CNT/3-3.HTM A 3- Company Country Telephony Ltr AAA AVICON AVIATION CONSULTANTS & AGENTS PAKISTAN AAB ABELAG AVIATION BELGIUM ABG AAC ARMY AIR CORPS UNITED KINGDOM ARMYAIR AAD MANN AIR LTD (T/A AMBASSADOR) UNITED KINGDOM AMBASSADOR AAE EXPRESS AIR, INC. (PHOENIX, AZ) UNITED STATES ARIZONA AAF AIGLE AZUR FRANCE AIGLE AZUR AAG ATLANTIC FLIGHT TRAINING LTD. UNITED KINGDOM ATLANTIC AAH AEKO KULA, INC D/B/A ALOHA AIR CARGO (HONOLULU, UNITED STATES ALOHA HI) AAI AIR AURORA, INC. (SUGAR GROVE, IL) UNITED STATES BOREALIS AAJ ALFA AIRLINES CO., LTD SUDAN ALFA SUDAN AAK ALASKA ISLAND AIR, INC. (ANCHORAGE, AK) UNITED STATES ALASKA ISLAND AAL AMERICAN AIRLINES INC. UNITED STATES AMERICAN AAM AIM AIR REPUBLIC OF MOLDOVA AIM AIR AAN AMSTERDAM AIRLINES B.V. NETHERLANDS AMSTEL AAO ADMINISTRACION AERONAUTICA INTERNACIONAL, S.A. MEXICO AEROINTER DE C.V. AAP ARABASCO AIR SERVICES SAUDI ARABIA ARABASCO AAQ ASIA ATLANTIC AIRLINES CO., LTD THAILAND ASIA ATLANTIC AAR ASIANA AIRLINES REPUBLIC OF KOREA ASIANA AAS ASKARI AVIATION (PVT) LTD PAKISTAN AL-AAS AAT AIR CENTRAL ASIA KYRGYZSTAN AAU AEROPA S.R.L. ITALY AAV ASTRO AIR INTERNATIONAL, INC. PHILIPPINES ASTRO-PHIL AAW AFRICAN AIRLINES CORPORATION LIBYA AFRIQIYAH AAX ADVANCE AVIATION CO., LTD THAILAND ADVANCE AVIATION AAY ALLEGIANT AIR, INC. (FRESNO, CA) UNITED STATES ALLEGIANT AAZ AEOLUS AIR LIMITED GAMBIA AEOLUS ABA AERO-BETA GMBH & CO., STUTTGART GERMANY AEROBETA ABB AFRICAN BUSINESS AND TRANSPORTATIONS DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF AFRICAN BUSINESS THE CONGO ABC ABC WORLD AIRWAYS GUIDE ABD AIR ATLANTA ICELANDIC ICELAND ATLANTA ABE ABAN AIR IRAN (ISLAMIC REPUBLIC ABAN OF) ABF SCANWINGS OY, FINLAND FINLAND SKYWINGS ABG ABAKAN-AVIA RUSSIAN FEDERATION ABAKAN-AVIA ABH HOKURIKU-KOUKUU CO., LTD JAPAN ABI ALBA-AIR AVIACION, S.L. -

Signatory Visa Waiver Program (VWP) Carriers

Visa Waiver Program (VWP) Signatory Carriers As of May 1, 2019 Carriers that are highlighted in yellow hold expired Visa Waiver Program Agreements and therefore are no longer authorized to transport VWP eligible passengers to the United States pursuant to the Visa Waiver Program Agreement Paragraph 14. When encountered, please remind them of the need to re-apply. # 21st Century Fox America, Inc. (04/07/2015) 245 Pilot Services Company, Inc. (01/14/2015) 258131 Aviation LLC (09/18/2013) 26 North Aviation Inc. 4770RR, LLC (12/06/2016) 51 CL Corp. (06/23/2017) 51 LJ Corporation (02/01/2016) 620, Inc. 650534 Alberta, Inc. d/b/a Latitude Air Ambulance (01/09/2017) 711 CODY, Inc. (02/09/2018) A A OK Jets A&M Global Solutions, Inc. (09/03/2014) A.J. Walter Aviation, Inc. (01/17/2014) A.R. Aviation, Corp. (12/30/2015) Abbott Laboratories Inc. (09/26/2012) ABC Aerolineas, S.A. de C.V. (d/b/a Interjet) (08/24/2011) Abelag Aviation NV d/b/a Luxaviation Belgium (02/27/2019) ABS Jets A.S. (05/07/2018) ACASS Canada Ltd. (02/27/2019) Accent Airways LLC (01/12/2015) Ace Aviation Services Corporation (08/24/2011) Ace Flight Center Inc. (07/30/2012) ACE Flight Operations a/k/a ACE Group (09/20/2015) Ace Flight Support ACG Air Cargo Germany GmbH (03/28/2011) ACG Logistics LLC (02/25/2019) ACL ACM Air Charter Luftfahrtgesellschaft GmbH (02/22/2018) ACM Aviation, Inc. (09/16/2011) ACP Jet Charter, Inc. (09/12/2013) Acromas Shipping Ltd. -

INFORME ESTADÍSTICO Sobre El Transporte Aéreo En República Dominicana

20 19 INFORME ESTADÍSTICO sobre el Transporte Aéreo en República Dominicana AÑO 8, NO. 6, ENERO - DICIEMBRE 2019, ISSN 2676-0533 , SANTO DOMINGO, D.N., REP. DOM. Informe Estadístico sobre el Transporte Aéreo de la República Dominicana 2019 Sección de Estadísticas División de Economía Informe Estadístico sobre el Transporte Aéreo en República Dominicana - 2019 Elaborado por: Sección de Estadísticas Carlos Santana Sabrina Pichardo Paola Massiel Mendoza Revisado por: División de Economía Francisco Figuereo Copyright 2020 Todos los derechos reservados Santo Domingo, Rep. Dom. 2 Junta de Aviación Civil de la República Dominicana Informe Estadístico sobre el Transporte Aéreo en República Dominicana - 2019 CONTENIDO GLOSARIO DE TÉRMINOS ........................................................................4 GLOSARIO DE SIGLAS ..............................................................................5 PALABRAS DEL PRESIDENTE ..................................................................7 RESUMEN EJECUTIVO ..............................................................................8 MOVIMIENTO DE PASAJEROS .................................................................10 MOVIMIENTO DE PASAJEROS POR AEROPUERTOS ............................14 MOVIMIENTO DE PASAJEROS POR LÍNEAS AÉREAS Y RUTAS ..........23 MOVIMIENTO DE PASAJEROS POR REGIÓN .........................................28 OPERACIONES AEROCOMERCIALES .....................................................37 INDICADORES AERONÁUTICOS Y CARGA AEROCOMERCIAL ............40 ANEXOS -

EN NÚMEROS Varias Líneas Aéreas Estadounidenses Reanudarán

06. 12. 28. EN NÚMEROS POR EL GPS RANCHO OLIVIER: Varias líneas aéreas Experimenta ideal para estadounidenses una desafi ante unas vacaciones reanudarán vuelos al país excursión otoñales y el Caribe en invierno. a África. familiares. año 1 • NÚmERo 08 • mENSuaL Paraíso familiar 2. puroturismo Año 1 • Número 08 Editorial check EL SECRETARIO IMPRESIONÓ. Durante un almuer- zo para la prensa ofre- cido recientemente por el Secretario de Turis- mo, Lic. Francisco Javier García Fernández, en el fECHaS PaRa RESERvaR reputado Restaurante go 16 de noviembre; cita con la histo- mación 809/ 501 6236, 334 6764 y Don Juan, del sector de Para el público en general: ria en Guayubín y Juan Gómez. Inédi- 687 7337, [email protected] Naco, en la Capital, este Noviembre: Día de la Constitu- tos documentos y otros testimonios ¡Check-in! habló y contestó pregun- ción, Jueves 6, laborable, se celebra sobre históricos acontecimientos. La tas de los periodistas por el lunes 10 (fi n de semana largo del 8 acción conjunta de José Martí y Máxi- CaP CaNa goLf CHamPioNSHiP espacio de más de una al 10) Busca las ofertas en la prensa - mo Gómez, en Juan Gómez. Y domin- Se inició la cuenta regresiva para hora, lo que permitió a Carretera de Jarabacoa. III Feria Hotelera Turismo Inmo- go 30 de noviembre: Maimón, Puer- que no te quedes fuera de la segunda la congregación “tomarle Foto: Frangella-Checcucci Photography biliario de la PUCMM, Campus San- to Plata y Mará Picá. Encuentro con versión del Cap Cana Champion- el pulso” al todavía nuevo funcionario. -

British Aerospace Bae J31 Jetstream Sorting: Serial Nr

British Aerospace BAe J31 Jetstream Sorting: Serial Nr. 29.08.2021 Ser.Nr. Type F/F Status Immatr. Operator Last Operator in service Engines Owner Rem. @airlinefleet.info M/Y until 601 BAe.J3102 1982 broken up G-WMCC none Maersk Air UK 08-1996 GA TPE331-10 Air Commuter ntu 602 BAe.J3101 1982 broken up N422MX none Eastern Metro Express 01-1998 GA TPE331-10 Mall Airways ntu 603 BAe.J3103 1982 broken up N603JS none Gold Aviation 01-2001 GA TPE331-10 broken up by 08-2005 604 BAe.J3101 1982 perm_wfu N78019 none Personal Airliner 05-2011 GA TPE331-10 to be broken up 605 BAe.J3102 1982 in service N408PP Corporate 06-2013 GA TPE331-10 Phil Pate 606 BAe.J3102 1982 perm_wfu LN-FAV none Coast Air 02-2007 GA TPE331-10 Royal Norwegian Air Force as instr. airframe 607 BAe.J3102 1983 perm_wfu N607BA none Professional Aviation Group 04-2008 GA TPE331-10 to be broken up 608 BAe.J3101 1983 broken up N608JX none Native American Air Serv. 03-1999 GA TPE331-10 broken up 03-2005 609 BAe.J3102 1983 broken up N609BA none Professional Aviation Group 05-2013 GA TPE331-10 610 BAe.J3103 1983 broken up G-JXTA none Jetstream Executive Travel 02-2011 GA TPE331-10 broken up 2016 611 BAe.J3101 1983 broken up N419MX none Eastern Metro Express 01-1991 GA TPE331-10 broken up 12-1997 612 BAe.J3102 1983 stored OM-NKD none SK Air 00-1999 GA TPE331-10 613 BAe.J3101 1983 in service N904EH Corporate 02-2019 GA TPE331-10 Aerostar 1 Inc. -

Informe Ejecutivo

INFORME EJECUTIVO: La Junta de Aviación Civil (JAC), como órgano del Estado Dominicano responsable de establecer la política superior de la aviación civil y regular los aspectos económicos del transporte aéreo, culminó el año 2015 con grandes logros institucionales que impactaron positivamente el turismo y la economía nacional, fortaleciendo al mismo tiempo el sector de la aviación civil dominicana. Las decisiones tomadas por el Pleno de la Junta estuvieron en consonancia con la política de Cielos Abiertos establecida dentro de la Estrategia Nacional de Desarrollo asumida por el Presidente de la República, Licenciado Danilo Medina, para impulsar el desarrollo de la industria turística nacional y el transporte aéreo en nuestra nación. En ese sentido, durante el pasado año la Junta de Aviación Civil en representación del Estado dominicano revisó, enmendó y concertó acuerdos de servicios aéreos (ASA) y Memorándum de Entendimiento (MOU), con diferentes países del mundo, garantizando la conectividad aérea de República Dominicana y creando las condiciones para la inversión y la apertura de nuevas rutas para el transporte aerocomercial. Dentro de los países con los que se concertaron nuevos acuerdos bilaterales de servicios aéreos podemos mencionar la República Checa, el reino de Finlandia, el Gran Ducado de Luxemburgo, la República de Serbia y el Reino de los Países Bajos respecto a Curazao. 1 Con Canadá, la República Federativa de Brasil, Haití, India, Israel, los Estados Unidos Mexicanos, Trinidad y Tobago y el Reino de Noruega se avanzan negociaciones para enmiendas y firmas definitivas de acuerdos de servicios aéreos bilaterales. Fruto de esos acuerdos, Puerto Plata comenzó a recibir en la temporada de invierno 2015, vuelos chárter provenientes de Finlandia así como de varias ciudades de Suecia, Polonia, Inglaterra y Holanda, dinamizando el flujo turístico hacia la región norte. -

Informe Estadístico Sobre El Transporte Aéreo En República Dominicana 2017

Informe Estadístico sobre el Transporte Aéreo en República Dominicana 2017 Febrero 2018 Santo Domingo, R.D. Elaborado por: Carlos E. Santana C. Sabrina Pichardo Paola Massiel Mendoza C. Revisado por: Francisco E. Guerrero S. Jesenia Ortiz Himilce Tejada Francisco Figuereo Copyright 2018 Todos los derechos reservados Santo Domingo, Rep. Dom. CONTENIDO GLOSARIO DE TÉRMINOS ........................................................................................... I GLOSARIO DE SIGLAS ............................................................................................... III PALABRAS DEL PRESIDENTE DE LA JUNTA DE AVIACIÓN CIVIL .................. V RESUMEN EJECUTIVO .............................................................................................. VI MOVIMIENTO GENERAL DE PASAJEROS ............................................................... 1 Entrada y salida de pasajeros 2017 ............................................................................... 1 Flujo de pasajeros por tipo de vuelo 2017 .................................................................... 1 Crecimiento en el tráfico de pasajeros 2010 - 2017 ...................................................... 2 MOVIMIENTO DE PASAJEROS POR AEROPUERTOS DOMINICANOS. .............. 2 Tráfico de pasajeros por aeropuertos 2017 ................................................................... 2 Variación en el movimiento de pasajeros por aeropuertos 2010 - 2017 ....................... 3 Principales líneas aéreas por aeropuertos .................................................................... -

COM LIST 3 CAR REGION Location Location Frequency Service Coordinates If AOC: Power/ Coverage/ Indicator/ Remarks Frecuencia Impl

COM LIST 3 CAR REGION Location Location Frequency Service Coordinates If AOC: Power/ Coverage/ indicator/ Remarks Frecuencia Impl. Coordinees Airline Potencia Cobertura Indicador de Cat. Aerolinea (W) (NM) Observaciones Lugar Lugar [MHz] Servicio Dates Coordenadas (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9) (10) (11) ANGUILLA THE TQPF 131.700 AOC NAT 18°12'23" N 063°03'12" W LIAT, Traffic 25 25 VALLEY/Clayton J. Office Lloyd Intl. Edition / Edición: 19 Diciembre 2019 Página 1 de 153 COM LIST 3 CAR REGION Location Location Frequency Service Coordinates If AOC: Power/ Coverage/ indicator/ Remarks Frecuencia Impl. Coordinees Airline Potencia Cobertura Indicador de Cat. Aerolinea (W) (NM) Observaciones Lugar Lugar [MHz] Servicio Dates Coordenadas (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9) (10) (11) ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA COCO POINT TAPT 122.950 FIS NAT OP 17°36'00" N 061°47'00" W 25 50 LODGE/ BARBUDA CODRINGTON/BAR TAPH 118.600 TWR NAT OP 17°36'00" N 061°47'00" W 25 25 BUDA TAPH 122.700 GP NAT OP 17°38'09" N 061°49'37" W 25 25 RUNWAY CONTROL LIGHTING TAPH 131.400 AOC NAT OP 17°36'00" N 061°47'00" W LIAT 25 25 SAINT JOHNS/V. C. TAPA 118.200 TWR ICAO OP 17°08'12" N 061°47'34" W 25 25 Bird Intl., Antigua TAPA 119.100 APP/L ICAO OP 17°08'12" N 061°47'34" W 25 75 TAPA 121.900 SMC ICAO OP 17°08'12" N 061°47'34" W 10 10 TAPA 122.650 AOC NAT OP 17°08'12" N 061°47'34" W Caribbean Star 25 25 Airlines Limited Edition / Edición: 19 Diciembre 2019 Página 2 de 153 COM LIST 3 CAR REGION Location Location Frequency Service Coordinates If AOC: Power/ Coverage/ indicator/ Remarks Frecuencia Impl. -

Enero 2019 Boletín Estadístico Sobre El Transporte Aéreo De La República Dominicana Enero 2019

Boletín Estadístico sobre el Transporte Aéreo en República Dominicana Enero 2019 Boletín Estadístico sobre el Transporte Aéreo de la República Dominicana Enero 2019 Sección de Estadísticas División de Economia BOLETÍN ESTADÍSTICO SOBRE EL TRANSPORTE AÉREO EN REPÚBLICA DOMINICANA - ENERO 2019 Contenido Entrada y salida de pasajeros ........................................................................1 Movimiento de pasajeros por aeropuertos ...................................................2 Movimiento de pasjeros por líneas aéreas ...................................................2 Líneas aéreas con crecimiento y decrecimiento ..........................................3 Movimiento de pasjeros por rutas aéreas.....................................................3 Rutas aéreas con crecimiento y decrecimiento ...........................................4 Líneas aéreas nacionales 2018 ......................................................................4 Operaciones en entrada y salida ...................................................................5 Operaciones aéreas por modalidad de vuelo ...............................................5 Operaciones aéreas por aeropuertos ............................................................5 Anexos..............................................................................................................6 SECCIÓN DE ESTADÍSTICAS DIVISIÓN DE ECONOMÍA DEL TRANSPORTE AÉREO2 BOLETÍN ESTADÍSTICO SOBRE EL TRANSPORTE AÉREO EN REPÚBLICA DOMINICANA - ENERO 2019 Movimiento de pasajeros Entrada y -

Oletín Estadístico Sobre El Transporte Aerocomercial De La Rep

Informe Estadístico sobre el Transporte Aerocomercial de la República Dominicana 1er. Semestre 2018 Julio 2018 Santo Domingo, R.D. Elaborado por: Carlos E. Santana C. Sabrina Pichardo Paola Massiel Mendoza C. Revisado por: Francisco E. Guerrero S. Copyright 2018 Todos los derechos reservados Santo Domingo, Rep. Dom. Contenido Resumen Ejecutivo ............................................................................................... 1 Movimiento de Pasajeros General ....................................................................... 3 Flujo de pasajeros en entradas y salidas 1er Semestre 2018: ......................................... 3 Comparativo de flujo de pasajeros por mes 1er Semestre 2017 - 2018 ........................... 3 Comparativo de flujo de pasajeros 1er Semestre 2017 - 2018 ......................................... 4 Flujo de pasajeros por tipo de vuelo 1er Semestre 2017 - 2018 ..................................... 4 Principales líneas aéreas ............................................................................................... 5 Principales rutas aéreas ................................................................................................. 5 Principales líneas aéreas con crecimiento ...................................................................... 6 Principales rutas aéreas con crecimiento ....................................................................... 6 ...................................................................................................................................... -

Resumen Ejecutivo

RESUMEN EJECUTIVO La Junta de Aviación Civil, como órgano asesor del Poder Ejecutivo en materia de política aerocomercial, que tiene a su cargo definir las políticas y estrategias para el desarrollo del transporte aéreo en la República Dominicana, ha concentrado sus esfuerzos en potenciar la competitividad, diversificación y sostenibilidad del sector de la aviación civil dominicana, a partir de los objetivos contemplados en su Plan Estratégico actual. En tal sentido, durante el año 2016, las decisiones tomadas por el Pleno de la Junta estuvieron en consonancia con la política de Cielos Abiertos establecida dentro de la Estrategia Nacional de Desarrollo (Ley No.1-12). asumida por el Presidente de la República, Licenciado Danilo Medina, para impulsar el desarrollo de la industria turística nacional y el transporte aéreo en nuestra nación, lo que resulta en importantes logros que impactan, tanto a la Institución en sí como a todo el sector, logros que van desde el incremento de operaciones aéreas, aprobación de nuevas rutas y frecuencias de vuelos, hasta la concertación de nuevos acuerdos de servicios aéreos, contribuyendo de esta manera al fortalecimiento del turismo, pilar número uno de nuestra economía y del transporte aéreo en nuestro país. En ese sentido, recientemente, durante la Novena Conferencia de Negociaciones de Servicios de Transporte Aéreo de la Organización de Aviación Civil Internacional-OACI (ICAN/2016), realizada en Nassau, Bahamas, entre los días 5 al 9 de diciembre de 2016, la República Dominicana pactó once (11) Acuerdos de Servicios Aéreos con igual número de países, Nicaragua, Jamaica, Singapur, Guyana, Nueva Zelanda, Estado de 1 Israel, los tres países escandinavos, Dinamarca, Suecia y Noruega, los mismos se corresponden a rúbrica de texto y firma de Memorándum de Entendimiento, y con respecto a los Acuerdos de Servicios Aéreos con el Estado de Kuwait y con la República Checa, el Lic.