Archaeological Investigation Csr Site, Pyrmont

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CITY of BOROONDARA Review of B-Graded Buildings in Kew, Camberwell and Hawthorn

CITY OF BOROONDARA Review of B-graded buildings in Kew, Camberwell and Hawthorn Prepared for City of Boroondara January 2007 Revised June 2007 VOLUME 4 BUILDINGS NOT RECOMMENDED FOR THE HERITAGE OVERLAY TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME 1 Main Report VOLUME 2 Individual Building Data Sheets – Kew VOLUME 3 Individual Building Data Sheets – Camberwell and Hawthorn VOLUME 4 Individual Building Data Sheets for buildings not recommended for the Heritage Overlay LOVELL CHEN 1 Introduction to the Data Sheets The following data sheets have been designed to incorporate relevant factual information relating to the history and physical fabric of each place, as well as to give reasons for the recommendation that they not be included in the Schedule to the Heritage Overlay in the Boroondara Planning Scheme. The following table contains explanatory notes on the various sections of the data sheets. Section on data sheet Explanatory Note Name Original and later names have been included where known. In the event no name is known, the word House appears on the data sheet Reference No. For administrative use by Council. Building type Usually Residence, unless otherwise stated. Address Address as advised by Council and checked on site. Survey Date Date when site visited. Noted here if access was requested but not provided. Grading Grading following review (C or Ungraded). In general, a C grading reflects a local level of significance albeit a comparatively low level when compared with other examples. In some cases, such buildings may not have been extensively altered, but have been assessed at a lower level of local significance. In other cases, buildings recommended to be downgraded to C may have undergone alterations or additions since the earlier heritage studies. -

AUSTRALIAN ROMANESQUE a History of Romanesque-Inspired Architecture in Australia by John W. East 2016

AUSTRALIAN ROMANESQUE A History of Romanesque-Inspired Architecture in Australia by John W. East 2016 CONTENTS 1. Introduction . 1 2. The Romanesque Style . 4 3. Australian Romanesque: An Overview . 25 4. New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory . 52 5. Victoria . 92 6. Queensland . 122 7. Western Australia . 138 8. South Australia . 156 9. Tasmania . 170 Chapter 1: Introduction In Australia there are four Catholic cathedrals designed in the Romanesque style (Canberra, Newcastle, Port Pirie and Geraldton) and one Anglican cathedral (Parramatta). These buildings are significant in their local communities, but the numbers of people who visit them each year are minuscule when compared with the numbers visiting Australia's most famous Romanesque building, the large Sydney retail complex known as the Queen Victoria Building. God and Mammon, and the Romanesque serves them both. Do those who come to pray in the cathedrals, and those who come to shop in the galleries of the QVB, take much notice of the architecture? Probably not, and yet the Romanesque is a style of considerable character, with a history stretching back to Antiquity. It was never extensively used in Australia, but there are nonetheless hundreds of buildings in the Romanesque style still standing in Australia's towns and cities. Perhaps it is time to start looking more closely at these buildings? They will not disappoint. The heyday of the Australian Romanesque occurred in the fifty years between 1890 and 1940, and it was largely a brick-based style. As it happens, those years also marked the zenith of craft brickwork in Australia, because it was only in the late nineteenth century that Australia began to produce high-quality, durable bricks in a wide range of colours. -

Cloud Download

1 Contents 4 Welcome 6 Jury Members 2017 9 Horbury Hunt Commercial Award 19 Horbury Hunt Residential Award 33 Bruce Mackenzie Landscape Award 43 Kevin Borland Masonry Award 53 Robin Dods Roof Tile Excellence Award 62 Horbury Hunt Commercial Award Entrants Index 62 Horbury Hunt Residential Award Entrants Index 63 Bruce Mackenzie Landscape Award Entrants Index 64 Kevin Borland Masonry Award Entrants Index 64 Robin Dods Roof Tile Excellence Award Entrants Index editor elizabeth mcintyre creative director sally woodward art direction natasha simmons 2 3 Welcome This year marks the eleventh Think Brick Awards – This year’s winners are to be congratulated for their celebrating outstanding architecture and the use imagination, skill and craftsmanship. I hope these of clay brick, concrete masonry and roof tiles in projects ignite your creativity and encourage the contemporary Australian design. Each year, the entries creation of your own designs championing the build on inspiration taken from the previous cohort of use of brick, block, pavers and roof tiles. finalists to present exemplary projects that use these materials in new and exciting ways. The 2017 finalists provide solutions to low-density elizabeth mcintyre housing, a variety of roof systems and landscape group ceo sanctuaries for the home. These innovative projects think brick, cmaa, rtaa show that masonry is being included increasingly in residential and commercial interiors, as well as to create clever connections between indoor and outdoor spaces. Glazed bricks continue to be featured as standout elements in all types of works, particularly in urban design. IS PIERCINGCreativity THE MUNDANE to find the marvelous.- Bill Moyers 5 4 5 cameron bruhn ben green debbie–lyn ryan alexis sanal murat sanal emma williamson elizabeth mcintyre architecture media tzannes mcbride charles ryan sanalarc sanalarc coda think brick Cameron Bruhn is the editorial director at Ben has worked on a large number of significant Debbie Ryan is the founding owner of McBride Alexis Sanal is a co-founder of SANALarc. -

Wahroonga and Waitara Railway Stations

WAHROONGA AND WAITARA RAILWAY STATIONS Two images by Robert Wilson on 12th August 2017 taken at Wahroonga. The top image shows the Sydney end of the Sydney-bound platform with the 1927 stepway, the 1938 entrance pergola and the trees planted after the removal of three fig trees in 2010. The sites of the gardens on each side of the corridor are shown by the lawn areas. The Coonanbarra Road footbridge is just visible in the distance. In the bottom image, the ‘heritage’ platform seats can be seen towards the Hornsby end of the Hornsby-bound platform with the seat ends embossed with “Wahroonga 1994”. The doors to the public toilets are visible, as is the former location of the garden. 1 CONTENTS THE BIRTH OF THE NORTH SHORE LINE 3 A FUNDING SHORTAGE IMPACTS ON CONSTRUCTION STANDARDS 4 MANIFESTATIONS OF THE IMPACT OF THE CHANGE OF ENGINEERS-IN-CHIEF 5 THE FIRST WAHROONGA STATION BUILDING 1890-1895 7 THE SECOND (PRESENT) WAHROONGA STATION BUILDING 1906 13 THE SECOND STATION MASTER’S RESIDENCE – 1909 18 WAHROONGA STATION GARDEN 21 SHELTER FOR TICKET COLLECTORS WAHROONGA – 1938 22 THE IMPACT OF WORLD WAR TWO ON WAHROONGA 22 WAHROONGA BOOKSTALL – 1957 23 IMPACT OF CITYRAIL AT WAHROONGA – 1993 24 REMOVAL OF PLATFORM VEGETATION WAHROONGA – 2010 28 CONTRIBUTION OF SYDNEY TRAINS 30 A HISTORY OF WAITARA STATION 32 ELEMENTS OF THE WAHROONGA AND WAITARA BUILDINGS THAT REFLECTED THE FEDERATION DESIGN INFLUENCES 35 THE FAMILY OF BUILDINGS TO WHICH THE 1906 WAHROONGA AND 1909 WAITARA STRUCTURES BELONG 35 COMPARISON WITH SIMILAR NORTH SHORE BUILDINGS 43 END REMARKS 46 2 THE BIRTH OF THE NORTH SHORE LINE Premier, George Dibbs, announced in 1883 that the North Shore line was to be built as one of 11 proposed branch lines proposed in that year. -

The Architectural Practice of Gerard Wight and William Lucas from 1885 to 1894

ABPL90382 Minor Thesis Jennifer Fowler Student ID: 1031421 22 June 2020 Boom Mannerism: The Architectural Practice of Gerard Wight and William Lucas from 1885 to 1894 Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Urban and Cultural Heritage, Melbourne School of Design, University of Melbourne Frontispiece: Herbert Percival Bennett Photograph of Collins Street looking east towards Elizabeth Street, c.1894, glass lantern slide, Gosbel Collection, State Library of Victoria. Salway, Wight and Lucas’ Mercantile Bank of 1888 with dome at centre above tram. URL: http://handle.slv.vic.gov.au/10381/54894. Abstract To date there has been no thorough research into the architectural practice of Wight and Lucas with only a few of their buildings referred to with brevity in histories and articles dealing with late nineteenth-century Melbourne architecture. The Boom era firm of Wight and Lucas from 1885 to 1894 will therefore be investigated in order to expand their catalogue of works based upon primary research and field work. Their designs will be analysed in the context of the historiography of the Boom Style outlined in various secondary sources. The practice designed numerous branches for the Melbourne Savings Bank in the metropolitan area and collaborated with other Melbourne architects when designing a couple of large commercial premises in the City of Melbourne. These Mannerist inspired classical buildings fit the general secondary descriptions of what has been termed the Boom Style of the 1880s and early 1890s. However, Wight and Lucas’ commercial work will be assessed in terms of its style, potential overseas influences and be compared to similar contemporary Melbourne architecture to firstly reveal their design methods and secondly, to attempt to give some clarity to the overall definition of Melbourne’s Boom era architecture and the firm’ place within this period. -

Download CNIB Craft Ideas

CREATING EDUCATIONAL TOYS AND ACTIVITIES FOR CHILDREN WHO ARE BLIND OR VISUALLY IMPAIRED JENNIFER UROSEVIC ORIENTATION AND MOBILITY INSTRUCTOR EARLY INTERVENTION SPECIALIST CANADIAN NATIONAL INSTITUTE FOR THE BLIND LEE-ANNE CROSS EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATOR EARLY INTERVENTION SPECIALIST CANADIAN NATIONAL INSTITUTE FOR THE BLIND Presented by Jennifer Urosevic and Lee-Anne Cross, Texas Focus Conference, June 2003. Use personal judgment and close supervision to ensure child‟s safety when using these activities. Presented by Jennifer Urosevic and Lee-Anne Cross, Texas Focus Conference, June 2003. Use personal judgment and close supervision to ensure child‟s safety when using these activities. INTRODUCTION Concept development and sensory awareness begin in infancy and continue to develop throughout a child‟s life. They are intertwined in every part of one‟s life, whether as a preschooler learning left from right, as a child learning Braille, or as a teenager learning to use cardinal directions. When these skills are continuously reinforced in all aspects of a child‟s life, and throughout daily routines, the child will ultimately gain greater independence. In our fast-paced society, it is tempting to search for the perfect toy which will teach children, while overlooking the many opportunities and tools which exist within our own homes and communities. The benefits of using household items and daily routines are many. We need to provide activities and opportunities which are rich, varied, and which help to develop concepts and life skills. It is easy to begin to search for the ideal toy, flashy and bright, which will teach these skills. And certainly, these types of toys do have a place in a child‟s play. -

How Did I Get Outside in the Blizzard? She Heard Sally Lil Cry Out

Anna’s Blizzard Anna's Blizzard INTERIOR for TPB.indd 1 6/1/17 2:18 PM Published by PEACHTREE PUBLISHERS 1700 Chattahoochee Avenue Atlanta, Georgia 30318-2112 www.peachtree-online.com Text © 2005 by Alison Hart Illustrations © 2005 by Paul Bachem First trade paperback edition published in 2017 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Loraine Joyner Book design by Melanie McMahon Ives Manufactured in China 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 (hardcover) 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 (trade paperback) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hart, Alison. Anna’s blizzard / by Alison Hart.— 1st ed. p. cm. Summary: Having never excelled at schoolwork, twelve-year-old Anna discovers that she may know a few things about survival when the 1888 Children’s Blizzard traps her and her classmates in their Nebraska schoolhouse. Includes bibilographical references ISBN 13: 978-1-56145-349-8 (hardcover) ISBN ??????? (trade paperback) [1. Survival—Fiction. 2. Blizzards—Fiction. 3. Schools—Fiction. 4. Nebraska— History—19th century—Fiction.] I. Title. PZ7.H256272Ar 2005 [Fic]—dc22 2005010825 Anna's Blizzard INTERIOR for TPB.indd 2 6/1/17 2:18 PM Anna’s Blizzard by Alison Hart Anna's Blizzard INTERIOR for TPB.indd 3 6/1/17 2:18 PM To brave girls everywhere —A. -

ARIA Charts, 1992-01-03 to 1992-03-08

AUSTRALIAN TOP 50 A A TRADE MARK REGD. THE AUSTRALIAN RECORD INDUSTRY ASSOCIATION LTD. SINGLES CHART PROUDLY BROUGHT TO YOU BY YOUR BOTTLER OF 'COCA—COLA' 1991 TITLE/ARTIST Co. Cat. No. STATE CHARTS 1 (EVERYTHING I DO) I DO IT FOR YOU Bryan Adams A2 PDR/POL 390 639-4 New South Wales 2 TINGLES (EP) Ratcat A roo/POL 878 165-4 1 (Everything I Do) I Do It For You 3 GREASE MEGAMIX Olivia Newton-John & John Travolta A PDR/POL 879 410-4 2 Tingles (EP) 4 THE HORSES Daryl Braithwaite A COLUMBIA 656617 4 3 The Horses GEF/BMG GEFCS 19039 4 More Than Words 5 YOU COULD BE MINE Guns n' Roses A 5 Grease Megamix 6 READ MY LIPS Melissa A PHON/POL 868 424-4 6 Read My Lips 7 MORE THAN WORDS Extreme A PDR/POL 390 634-4 7 You Could Be Mine 8 I'VE BEEN THINKING ABOUT YOU Londonbeat A ANX/BMG CSANX 0014 8 I've Been Thinking About You 9 JOYRIDE Roxette A EMI 2547-4 9 Better 101'm Too Sexy 10 THE SHOOP SHOOP SONG (IT'S IN HIS KISS) Cher A EPIC 656666 4 11 DO THE BARTMAN The Simpsons • GEF/BMG 543919665-4 Victoria & Tasmania 12 UNFORGETTABLE Natalie Cole With Nat "King" Cole • WARNER 755964875-4 1 (Everything I Do) I Do It For You 13 I'M TOO SEXY R.S.F. (Right Said Fred) A LIB/FES C 10503 2 Grease Megamix 14 LOVE ... WILL BE DONE Martika A COLUMBIA 656975 4 3 Tingles (EP) VIR/EMI VOZC 094 4 Read My Lips 15 I TOUCH MYSELF Divinyls A 5 I've Been Thinking About You 16 RUSH Big Audio Dynamite II • COLUMBIA 656978 4 6 More Than Words 17 FANTASY Black Box • BMG CS 3895 1 You Could Be Mine 18 RHYTHM OF MY HEART Rod Stewart • WARNER 543919374-4 8 The Horses 19 RUSH RUSH Paula Abdul • VIR/EMI VUSC 38 9 Joyride 10 Fantasy 20 BETTER The Screaming Jets • roo/POL 878 814-4 21 I WANNA SEX YOU UP Color Me Badd • WARNER 543919382-4 Queensland 22 ICE ICE BABY Vanilla Ice A EMI 2504-4 1 (Everything I Do) I Do It For You 23 SADNESS PART 1 Enigma • VIR/EMI DINSC 101 2 The Horses 24 HERE I AM (COME AND TAKE ME) UB40 • VIR/EMI TCDEPC 34 3 The Shoop Shoop Song (It's In His Kiss) LIB/FES C 10380 4 You Could Be Mine 25 3 A.M. -

Moving Food and Drink Manual Handling Solutions for the Food and Drink Industries

Health and Safety Executive Moving food and drink Manual handling solutions for the food and drink industries This is a free-to-download, web-friendly version of HSG196 (First edition, published 2000). This version has been adapted for online use from HSE’s current printed version. You can buy the book at www.hsebooks.co.uk and most good bookshops. ISBN 978 07176 1731 9 Price £15.95 This book is for all employers in the food and drink industries whose work might be putting their employees’ muscles and joints at risk of damage. It shows simple and cost-effective ways of reducing both acute and chronic injuries – the solutions described were successful answers to actual problems experienced by companies. The case studies cover raw materials handling, production, packing into containers, stacking/moving containers, handling equipment and off-site delivery. HSE Books Health and Safety Executive © Crown copyright 2000 First published 2000 ISBN 978 07176 1731 9 You may reuse this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view the licence visit www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/, write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email [email protected]. Some images and illustrations may not be owned by the Crown so cannot be reproduced without permission of the copyright owner. Enquiries should be sent to [email protected]. This guidance is issued by the Health and Safety Executive. Following the guidance is not compulsory and you are free to take other action. -

Pdf, 512.04 KB

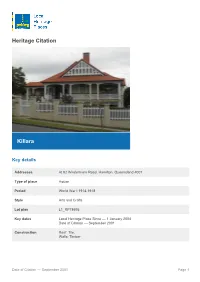

Heritage Citation Killara Key details Addresses At 92 Windermere Road, Hamilton, Queensland 4007 Type of place House Period World War I 1914-1918 Style Arts and Crafts Lot plan L1_RP78695 Key dates Local Heritage Place Since — 1 January 2004 Date of Citation — September 2001 Construction Roof: Tile; Walls: Timber Date of Citation — September 2001 Page 1 People/associations Francis Richard Hall (Architect) Criterion for listing (A) Historical; (D) Representative; (E) Aesthetic; (H) Historical association Killara is significant as an excellent example of a Federation style residence in Brisbane. Designed by the architectural firm of F.R. Hall, it shows the stylistic influence of the work of Robin Dods. It was built in Hamilton circa 1918 at a time when Hamilton was changing from an area of large luxurious estates to one of fine suburban homes on smaller allotments. It has both historical and aesthetic significance and is included in the Brisbane City Council Heritage Trail for Hamilton. History Killara was built circa 1918 for Mr and Mrs John Ambrose Walsh who purchased four adjacent allotments in Windermere Road in 1917. An elegant, Federation style home, its large garden once included a tennis court on the eastern side of the house. Like many houses at Hamilton built during the early decades of the 20th century, Killara was constructed on land subdivided from a grand 19th century estate. It is situated on land which was part of 17 acres acquired by Deed of Grant by pastoralist James Sutherland in 1855. It is believed that Sutherland built a house on this estate which was later demolished and that a second house, Windermere, was built for his daughter, Ruth, and her husband, John George Appel, around 1886. -

Projects • Reports • Resources • Articles • Reviews

wine makiDigital V– – Volume 50 No 2 2018 IN THIS ISSUE: GTA NEWS .................................................3 ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIA PART 3: Indigenous Protected Areas ............... 25 WHAT’S HAPPENING IN SCHOOLS? – Digital Literacy & Digital Fluency .... 29 – Virtual Excursions .............................. 31 – In the age of alternative facts, we need to teach our kids to uncover the truth .............................. 32 FEATURE ARTICLE: URBAN PLACES – Sydney’s Urban Future ...................... 35 – Fieldwork – Marrickville ................... 51 – Fieldwork – The Greenway (Waratah Mills) ................................... 55 – Stage 5 Assessment: Revitalisation of the White Bay Power Station ....... 57 CURRICULUM LINKS – South Korea, the Winter Olympics .... 61 PROJECTS • REPORTS • RESOURCES • ARTICLES • REVIEWS EXECUTIVE 2018 President Lorraine Chaffer Vice Presidents Susan Caldis Grant Kleeman Sharon McLean Louise Swanson Minutes Secretary Milton Brown OFFICE OF THE GEOGRAPHY TEACHERS’ Honorary Treasurer ASSOCIATION OF NEW SOUTH WALES Grant Kleeman ABN 59246850128 Councillors Address: 67–73 St Hilliers Road, Auburn NSW Paul Alger Postal Address: PO Box 699 Lidcombe NSW 1825, Australia Karen Bowden Telephone: (02) 9716 0378, Fax: (02) 9564 2342 Matt Carroll Website: www.gtansw.org.au Drew Collins Email: [email protected] Michael Da Roza (ACT) Catherine Donnelly ANNUAL MEMBERSHIP (Subscriptions include GST) Personal membership $90.00 Adrian Harrison Corporate membership (school, department or business) $190.00 Keith Hopkins Concessional membership (retiree, part-time teacher or student) $40.00 Nick Hutchinson Primary corporate membership $50.00 Grace Larobina David Latimer John Lewis Alexandra Lucas John Petts Martin Pluss Melinda Rowe GEOGRAPHY BULLETIN Cover: Sydney from Centrepoint Tower. Image source: Wikimedia Commons Editor The Geography Bulletin is a quarterly journal of The Geography Teachers’ Association Lorraine Chaffer of New South Wales. -

Transit by Ben Aaronovitch Prologue the Doctor Stood Alone on A

Transit By Ben Aaronovitch Prologue The Doctor stood alone on a Devonian beach and tried to persuade the lungfish to return to the sea. 'You won't like it,' said the Doctor. He noticed that the fish's fins had become short stubby legs. It had become an Ichthyostega, the first true amphibian. The Doctor checked his watch. About two million years early at that. 'You're making a big mistake,' said the Doctor. The amphibian ignored him, its flat head fixed on the line of cool vegetation ahead. It had covered a quarter of the distance across the hot white sand. 'I know it's crowded in there,' pleaded the Doctor. 'I know the food chain is overstocked, I know it's a fish-eat-fish ocean ...' He trailed off. The gill slits had healed up, the legs lengthened. Claws sprouted from the feet. The panting mouth was full of teeth. From across the sea came the sound of thunder. 'Don't do it," said the Doctor. But too late. The reptile was suddenly flushed with hot blood. Hair sprouted over its body, it got off its belly and surged up the beach, getting smaller all the time. By the time the Doctor caught up with it, the mammal was five centimetres long and cowering behind a shell. From the forest ahead came the crash and roar of gigantic lizards. The Doctor hunkered down and stared at the rodent. Its small eyes gazed over the half of the beach that remained. The Doctor felt that it should at least look terrified but it didn't.