World Bank Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Punctuality Statistics Economic Regulation Group Aviation Data Unit

Punctuality Statistics Economic Regulation Group Aviation Data Unit Birmingham, Edinburgh, Gatwick, Glasgow, Heathrow, London City, Luton, Manchester, Newcastle, Stansted Full and Summary Analysis June 1997 Disclaimer The information contained in this report will be compiled from various sources and it will not be possible for the CAA to check and verify whether it is accurate and correct nor does the CAA undertake to do so. Consequently the CAA cannot accept any liability for any financial loss caused by the persons reliance on it. Contents Foreword Introductory Notes Full Analysis – By Reporting Airport Birmingham Edinburgh Gatwick Glasgow Heathrow London City Luton Manchester Newcastle Stansted Full Analysis With Arrival / Departure Split – By A Origin / Destination Airport B C – E F – H I – L M – N O – P Q – S T – U V – Z Summary Analysis FOREWORD 1 CONTENT 1.1 Punctuality Statistics: Heathrow, Gatwick, Manchester, Glasgow, Birmingham, Luton, Stansted, Edinburgh, Newcastle and London City - Full and Summary Analysis is prepared by the Civil Aviation Authority with the co-operation of the airport operators and Airport Coordination Ltd. Their assistance is gratefully acknowledged. 2 ENQUIRIES 2.1 Statistics Enquiries concerning the information in this publication and distribution enquiries concerning orders and subscriptions should be addressed to: Civil Aviation Authority Room K4 G3 Aviation Data Unit CAA House 45/59 Kingsway London WC2B 6TE Tel. 020-7453-6258 or 020-7453-6252 or email [email protected] 2.2 Enquiries concerning further analysis of punctuality or other UK civil aviation statistics should be addressed to: Tel: 020-7453-6258 or 020-7453-6252 or email [email protected] Please note that we are unable to publish statistics or provide ad hoc data extracts at lower than monthly aggregate level. -

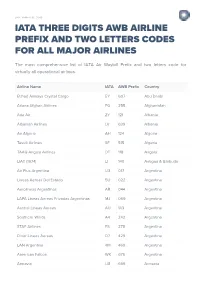

Iata Three Digits Awb Airline Prefix and Two Letters Codes for All Major Airlines

SEPTEMBER 18, 2019 IATA THREE DIGITS AWB AIRLINE PREFIX AND TWO LETTERS CODES FOR ALL MAJOR AIRLINES The most comprehensive list of IATA Air Waybill Prefix and two letters code for virtually all operational airlines. Airline Name IATA AWB Prefix Country Etihad Airways Crystal Cargo EY 607 Abu Dhabi Ariana Afghan Airlines FG 255 Afghanistan Ada Air ZY 121 Albania Albanian Airlines LV 639 Albania Air Algerie AH 124 Algeria Tassili Airlines SF 515 Algeria TAAG Angola Airlines DT 118 Angola LIAT (1974) LI 140 Antigua & Barbuda Air Plus Argentina U3 017 Argentina Lineas Aereas Del Estado 5U 022 Argentina Aerolineas Argentinas AR 044 Argentina LAPA Lineas Aereas Privadas Argentinas MJ 069 Argentina Austral Lineas Aereas AU 143 Argentina Southern Winds A4 242 Argentina STAF Airlines FS 278 Argentina Dinar Lineas Aereas D7 429 Argentina LAN Argentina 4M 469 Argentina American Falcon WK 676 Argentina Armavia U8 669 Armenia Airline Name IATA AWB Prefix Country Armenian International Airways MV 904 Armenia Air Armenia QN 907 Armenia Armenian Airlines R3 956 Armenia Jetstar JQ 041 Australia Flight West Airlines YC 060 Australia Qantas Freight QF 081 Australia Impulse Airlines VQ 253 Australia Macair Airlines CC 374 Australia Australian Air Express XM 524 Australia Skywest Airlines XR 674 Australia Kendell Airlines KD 678 Australia East West Airlines EW 804 Australia Regional Express ZL 899 Australia Airnorth Regional TL 935 Australia Lauda Air NG 231 Austria Austrian Cargo OS 257 Austria Eurosky Airlines JO 473 Austria Air Alps A6 527 Austria Eagle -

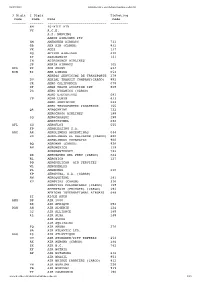

3 Digit 2 Digit Ticketing Code Code Name Code ------6M 40-MILE AIR VY A.C.E

06/07/2021 www.kovrik.com/sib/travel/airline-codes.txt 3 Digit 2 Digit Ticketing Code Code Name Code ------- ------- ------------------------------ --------- 6M 40-MILE AIR VY A.C.E. A.S. NORVING AARON AIRLINES PTY SM ABERDEEN AIRWAYS 731 GB ABX AIR (CARGO) 832 VX ACES 137 XQ ACTION AIRLINES 410 ZY ADALBANAIR 121 IN ADIRONDACK AIRLINES JP ADRIA AIRWAYS 165 REA RE AER ARANN 684 EIN EI AER LINGUS 053 AEREOS SERVICIOS DE TRANSPORTE 278 DU AERIAL TRANSIT COMPANY(CARGO) 892 JR AERO CALIFORNIA 078 DF AERO COACH AVIATION INT 868 2G AERO DYNAMICS (CARGO) AERO EJECUTIVOS 681 YP AERO LLOYD 633 AERO SERVICIOS 243 AERO TRANSPORTES PANAMENOS 155 QA AEROCARIBE 723 AEROCHAGO AIRLINES 198 3Q AEROCHASQUI 298 AEROCOZUMEL 686 AFL SU AEROFLOT 555 FP AEROLEASING S.A. ARG AR AEROLINEAS ARGENTINAS 044 VG AEROLINEAS EL SALVADOR (CARGO) 680 AEROLINEAS URUGUAYAS 966 BQ AEROMAR (CARGO) 926 AM AEROMEXICO 139 AEROMONTERREY 722 XX AERONAVES DEL PERU (CARGO) 624 RL AERONICA 127 PO AEROPELICAN AIR SERVICES WL AEROPERLAS PL AEROPERU 210 6P AEROPUMA, S.A. (CARGO) AW AEROQUETZAL 291 XU AEROVIAS (CARGO) 316 AEROVIAS COLOMBIANAS (CARGO) 158 AFFRETAIR (PRIVATE) (CARGO) 292 AFRICAN INTERNATIONAL AIRWAYS 648 ZI AIGLE AZUR AMM DP AIR 2000 RK AIR AFRIQUE 092 DAH AH AIR ALGERIE 124 3J AIR ALLIANCE 188 4L AIR ALMA 248 AIR ALPHA AIR AQUITAINE FQ AIR ARUBA 276 9A AIR ATLANTIC LTD. AAG ES AIR ATLANTIQUE OU AIR ATONABEE/CITY EXPRESS 253 AX AIR AURORA (CARGO) 386 ZX AIR B.C. 742 KF AIR BOTNIA BP AIR BOTSWANA 636 AIR BRASIL 853 AIR BRIDGE CARRIERS (CARGO) 912 VH AIR BURKINA 226 PB AIR BURUNDI 919 TY AIR CALEDONIE 190 www.kovrik.com/sib/travel/airline-codes.txt 1/15 06/07/2021 www.kovrik.com/sib/travel/airline-codes.txt SB AIR CALEDONIE INTERNATIONAL 063 ACA AC AIR CANADA 014 XC AIR CARIBBEAN 918 SF AIR CHARTER AIR CHARTER (CHARTER) AIR CHARTER SYSTEMS 272 CCA CA AIR CHINA 999 CE AIR CITY S.A. -

Air Charter Statistics Statistiques Des Affrètements Aériens

Catalogue no. 51-207-XIB No 51-207-XIB au catalogue Air Statistiques des Charter affrètements Statistics aériens 1997 1997 Statistics Statistique Canada Canada Data in many forms Des données sous plusieurs formes Statistics Canada disseminates data in a variety of forms. Statistique Canada diffuse les données sous formes diverses. In addition to publications, both standard and special Outre les publications, des totalisations habituelles et spéciales tabulations are offered. Data are available on the Internet, sont offertes. Les données sont disponibles sur Internet, disque compact disc, diskette, computer printouts, microfiche and compact, disquette, imprimé d’ordinateur, microfiche et microfilm, microfilm, and magnetic tape. Maps and other geographic et bande magnétique. Des cartes et d’autres documents de reference materials are available for some types of data. référence géographiques sont disponibles pour certaines sortes de Direct online access to aggregated information is possible données. L’accès direct à des données agrégées est possible par through CANSIM, Statistics Canada’s machine-readable le truchement de CANSIM, la base de données ordinolingue et le database and retrieval system. système d’extraction de Statistique Canada. How to obtain more information Comment obtenir d’autres renseignements Inquiries about this product and related statistics or Toute demande de renseignements au sujet du présent produit ou services should be directed to: Aviation Statistics Centre, au sujet de statistiques ou de services connexes doit -

Iata Three Digits Awb Airline Prefix and Two Letters Codes for All Major Airlines

SEPTEMBER 18, 2019 IATA THREE DIGITS AWB AIRLINE PREFIX AND TWO LETTERS CODES FOR ALL MAJOR AIRLINES The most comprehensive list of IATA Air Waybill Prefix and two letters code for virtually all operational airlines. Airline Name IATA AWB Prefix Country Etihad Airways Crystal Cargo EY 607 Abu Dhabi Ariana Afghan Airlines FG 255 Afghanistan Ada Air ZY 121 Albania Albanian Airlines LV 639 Albania Air Algerie AH 124 Algeria Tassili Airlines SF 515 Algeria TAAG Angola Airlines DT 118 Angola LIAT (1974) LI 140 Antigua & Barbuda Air Plus Argentina U3 017 Argentina Lineas Aereas Del Estado 5U 022 Argentina Aerolineas Argentinas AR 044 Argentina LAPA Lineas Aereas Privadas Argentinas MJ 069 Argentina Austral Lineas Aereas AU 143 Argentina Southern Winds A4 242 Argentina STAF Airlines FS 278 Argentina Dinar Lineas Aereas D7 429 Argentina LAN Argentina 4M 469 Argentina American Falcon WK 676 Argentina Armavia U8 669 Armenia Airline Name IATA AWB Prefix Country Armenian International Airways MV 904 Armenia Air Armenia QN 907 Armenia Armenian Airlines R3 956 Armenia Jetstar JQ 041 Australia Flight West Airlines YC 060 Australia Qantas Freight QF 081 Australia Impulse Airlines VQ 253 Australia Macair Airlines CC 374 Australia Australian Air Express XM 524 Australia Skywest Airlines XR 674 Australia Kendell Airlines KD 678 Australia East West Airlines EW 804 Australia Regional Express ZL 899 Australia Airnorth Regional TL 935 Australia Lauda Air NG 231 Austria Austrian Cargo OS 257 Austria Eurosky Airlines JO 473 Austria Air Alps A6 527 Austria Eagle -

Use CTL/F to Search for INACTIVE Airlines on This Page - Airlinehistory.Co.Uk

The World's Airlines Use CTL/F to search for INACTIVE airlines on this page - airlinehistory.co.uk site search by freefind search Airline 1Time (1 Time) Dates Country A&A Holding 2004 - 2012 South_Africa A.T. & T (Aircraft Transport & Travel) 1981* - 1983 USA A.V. Roe 1919* - 1920 UK A/S Aero 1919 - 1920 UK A2B 1920 - 1920* Norway AAA Air Enterprises 2005 - 2006 UK AAC (African Air Carriers) 1979* - 1987 USA AAC (African Air Charter) 1983*- 1984 South_Africa AAI (Alaska Aeronautical Industries) 1976 - 1988 Zaire AAR Airlines 1954 - 1987 USA Aaron Airlines 1998* - 2005* Ukraine AAS (Atlantic Aviation Services) **** - **** Australia AB Airlines 2005* - 2006 Liberia ABA Air 1996 - 1999 UK AbaBeel Aviation 1996 - 2004 Czech_Republic Abaroa Airlines (Aerolineas Abaroa) 2004 - 2008 Sudan Abavia 1960^ - 1972 Bolivia Abbe Air Cargo 1996* - 2004 Georgia ABC Air Hungary 2001 - 2003 USA A-B-C Airlines 2005 - 2012 Hungary Aberdeen Airways 1965* - 1966 USA Aberdeen London Express 1989 - 1992 UK Aboriginal Air Services 1994 - 1995* UK Absaroka Airways 2000* - 2006 Australia ACA (Ancargo Air) 1994^ - 2012* USA AccessAir 2000 - 2000 Angola ACE (Aryan Cargo Express) 1999 - 2001 USA Ace Air Cargo Express 2010 - 2010 India Ace Air Cargo Express 1976 - 1982 USA ACE Freighters (Aviation Charter Enterprises) 1982 - 1989 USA ACE Scotland 1964 - 1966 UK ACE Transvalair (Air Charter Express & Air Executive) 1966 - 1966 UK ACEF Cargo 1984 - 1994 France ACES (Aerolineas Centrales de Colombia) 1998 - 2004* Portugal ACG (Air Cargo Germany) 1972 - 2003 Colombia ACI -

EUNL1998 EUROPEAN UTILITY NEWSLETTER 1�98 ****************************************************************************** * * * Editor: Andreas Ibold, Mittelstr

EUNL1998 EUROPEAN UTILITY NEWSLETTER 1-98 ****************************************************************************** * * * Editor: Andreas Ibold, Mittelstr. 10, D-47441 Moers, GERMANY * * Tel.: (49) 02841 / 178529 ***** e-mail: [email protected] * * Home page: http://members.aol.com/aibold/EUNL.htm * * Logs: http://members.aol.com/aibold/logs.htm * * Treasurer: Norbert Reiner * * Membership fees to: Badische Beamtenbank Karlsruhe * * Konto Nr.: 2038005 BLZ: 66090800 * * Dispatcher: Thomas Ingenpass * * ---------------------------------------------------------------------------* * Membership fees for the printed copies: payable to the treasurer * * Germany: 20 DM; Europe: 20 DM (13 $); Overseas: 25 $ or the equivalent in * * foreign currency - no cheques please!!) * * * * Deadline: 20th of the month!!! * * * ****************************************************************************** Hi there! A Happy New Year to all PVR`s (paper version readers) and IR`s (Internet readers) and welcome to the first edition in new 1998. We are starting again with some nice stuff. Thanks for all the X-mas greetings which reached me! N D B 247 0224 GM Gomel BLR id zeTC 255 0148 H Wroclaw-Strachowice POL id zeTC 258 0106 RAD Radovest BUL id zeTC 265 0140 KAV Kavran-Pula HRV id zeTC 267,5 0146 OPW Bucuresti-Otopeni ROU id mo76+zeTC 269 0712 BH Blavandshuk DNK id+dash ti26 274 0114 JL Jalta UKR id zeTC 275 0016 VG Haugesund-Vaga NOR id zeTC 276,5 0019 BW Bremen West D id zeTC 277 0018 GOL Golyama BUL id+tone zeTC 284 0126 VN Capo Vaticano Lt. I id+tone zeTC 284 0152 GRN Gorna BUL id+tone zeTC 284,5 0055 PR Porkkala Lt. FIN id zeTC 285 0630 DU UNID ? id (8x=1min) zeTC 285 1648 PDV Padova I id moI 287,3 2331 HA Haifa ISR id+tone mo76 288 0005 DW Szymany POL id zeTC 291 1652 CF Capo Ferro I id+tone moI 297 1018 CH Civitavecchia I id+tone moI 298 1315 LI Livorno I id+tone moI 300,5 0020 LA Lista NOR id+dash zeTC+ti26 306 1020 PAR Parma I id moI 306,5 0434 UT Utsira NOR id+tone mo76 309,5 0137 OD Oddesskiy Lt. -

Zusammenfassung

Mitteilungen der Österreichischen Geographischen Gesellschaft, 151. Jg. (Jahresband), Wien 2009, S. 241–276 Romania’s aiRlines and aiRpoRts duRing tRansition with paRticulaR RefeRence to the west Region Remus Creţan, Timişoara, David TurnoCk, Leicester, and Maarten Wassing, Utrecht* with 1 Fig. and 7 Tab. in the text ConTenTs Zusammenfassung ...............................................................................................241 Summary .............................................................................................................242 1 Introduction ...................................................................................................242 2 Historical summary ........................................................................................243 3 Airlines during transition ...............................................................................246 4 Romanian airports during transition ...............................................................254 5 The case of the West Region and its cross-border relations .............................266 6 Conclusion .....................................................................................................273 7 Bibliography ..................................................................................................274 Zusammenfassung Die Fluggesellschaften und Flughäfen Rumäniens unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Westregion Der Flugverkehr war in den letzten Jahren eine der dynamischesten Branchen der rumänischen Wirtschaft. Nach -

Airline Business Models and Their Respective Carbon Footprint: Final Report

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Cranfield CERES Airline Business Models and their respective carbon footprint: Final Report Main Thematic Area: Economics Keith Mason and Chikage Miyoshi Cranfield University January 2009 _____________________________________________________________________________________________________ About Omega Omega is a one-stop-shop providing impartial world-class academic expertise on the environmental issues facing aviation to the wider aviation sector, Government, NGO’s and society as a whole. Its aim is independent knowledge transfer work and innovative solutions for a greener aviation future. Omega’s areas of expertise include climate change, local air quality, noise, aircraft systems, aircraft operations, alternative fuels, demand and mitigation policies. Omega draws together world-class research from nine major UK universities. It is led by Manchester Metropolitan University with Cambridge and Cranfield. Other partners are Leeds, Loughborough, Oxford, Reading, Sheffield and Southampton. Launched in 2007, Omega is funded by the Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE). www.omega.mmu.ac.uk Report prepared by Principal Investigator: Dr Keith Mason Reviewed / checked by Andreas Schafer/Omega Office © Copyright MMU 2009 Page 2 www.omega.mmu.ac.uk _____________________________________________________________________________________________________ Airline Business Models – Final Report Airline Business Models and their respective carbon footprint: -

Airlines IATA Codes

Airlines IATA Codes Airline Name IATA AWB Prefix Country AB Airlines Cargo 7L 698 United Kingdom ABSA Cargo Airline M3 549 Brazil ABX Air GB 832 United States ACESͲAerolineas Central de Colombia VX 137 Colombia Ada Air ZY 121 Albania Adria Airways JP 165 Slovenia AECAͲAeroservicios Ecuatorianos CA 2A 746 Ecuador Aegean Airlines A3 390 Greece Aer Lingus Cargo EI 53 Ireland Aero Asia International E4 532 Pakistan Aero California JR 78 Mexico Aero Caribbean 7L 164 Cuba Aero Continente N6 929 Peru Aero Costa Rica ML 802 Peru Aero Lanka QL 383 Sri Lanka Aero Lloyd YP 633 Germany Aero Zambia Z9 509 South Africa Aerochago Airlines G3 198 Dominican Republic AeroflotͲCargo SU 507 Russia AeroflotͲDon D9 733 Russia AeroflotͲNord 5N 316 Russia AeroflotͲRussian Airlines SU 555 Russia Aerogaviota KG 854 Cuba Aerolineas Argentinas AR 44 Argentina Aerolineas Dominicanas YU 725 Dominican Republic Aerolitoral 5D 642 Mexico Aeromar BQ 926 United States Aeromexico AM 139 Mexico Aeromexpress Cargo QO 976 Mexico Aeronaves del Peru XX 624 Peru Aeroperu PL 210 Peru Aeropostal Alas de Venezuela VH 152 Venezuela Aerorepublica SA P5 845 Colombia Aerosur 5L 275 Bolivia AeroSvit Airlines VV 870 Ukraine Aerounion 6R 873 Mexico Aerovias Caribe QA 723 Mexico Affretair ZL 292 Zimbabwe Africa West FK 858 Togo Afriqiyah Airways 8U 546 Libya Air Afrique RK 92 Ivory Coast Air Alfa H7 770 Turkey Air Algerie AH 124 Algeria Air Alliance Inc 3J 188 Canada Air Alps A6 527 Austria Air Armenia QN 907 Armenia Air Astana 4L 465 Kazakhstan Air Atlanta Icelandic CC 318 Iceland Air Atlantic 9A 574 Canada Air Atlantique 7M 336 United Kingdom Air Aurora AX 386 United States Air Austral UU 760 Reunion Air Baltic BT 657 Latvia Airlines IATA Codes Air Berlin AB 745 Germany Air Bosna JA 995 BosniaͲHerzegovina Page 1 of 14 Airline Name IATA AWB Prefix Country Air Botswana BP 636 Botswana Air Burkina 2J 226 Burkina Faso Air Caledonie TY 190 France Air Caledonie International SB 63 New Caledonia Air Canada AC 14 Canada Air Caribbean XC 918 Neth. -

Airline Name IATA AWB Prefix Country AB Airlines Cargo 7L 698

Airline Name IATA AWB Prefix Country AB Airlines Cargo 7L 698 United Kingdom ABSA Cargo Airline M3 549 Brazil ABX Air GB 832 United States ACES‐Aerolineas Central de Colombia VX 137 Colombia Ada Air ZY 121 Albania Adria Airways JP 165 Slovenia AECA‐Aeroservicios Ecuatorianos CA 2A 746 Ecuador Aegean Airlines A3 390 Greece Aer Lingus Cargo EI 53 Ireland Aero Asia International E4 532 Pakistan Aero California JR 78 Mexico Aero Caribbean 7L 164 Cuba Aero Continente N6 929 Peru Aero Costa Rica ML 802 Peru Aero Lanka QL 383 Sri Lanka Aero Lloyd YP 633 Germany Aero Zambia Z9 509 South Africa Aerochago Airlines G3 198 Dominican Republic Aeroflot‐Cargo SU 507 Russia Aeroflot‐Don D9 733 Russia Aeroflot‐Nord 5N 316 Russia Aeroflot‐Russian Airlines SU 555 Russia Aerogaviota KG 854 Cuba Aerolineas Argentinas AR 44 Argentina Aerolineas Dominicanas YU 725 Dominican Republic Aerolitoral 5D 642 Mexico Aeromar BQ 926 United States Aeromexico AM 139 Mexico Aeromexpress Cargo QO 976 Mexico Aeronaves del Peru XX 624 Peru Aeroperu PL 210 Peru Aeropostal Alas de Venezuela VH 152 Venezuela Aerorepublica SA P5 845 Colombia Aerosur 5L 275 Bolivia AeroSvit Airlines VV 870 Ukraine Aerounion 6R 873 Mexico Aerovias Caribe QA 723 Mexico Affretair ZL 292 Zimbabwe Africa West FK 858 Togo Afriqiyah Airways 8U 546 Libya Air Afrique RK 92 Ivory Coast Air Alfa H7 770 Turkey Air Algerie AH 124 Algeria Air Alliance Inc 3J 188 Canada Air Alps A6 527 Austria Air Armenia QN 907 Armenia Air Astana 4L 465 Kazakhstan Air Atlanta Icelandic CC 318 Iceland Air Atlantic 9A 574 Canada Air Atlantique 7M 336 United Kingdom Air Aurora AX 386 United States Air Austral UU 760 Reunion Air Baltic BT 657 Latvia Air Berlin AB 745 Germany Air Bosna JA 995 Bosnia‐Herzegovina Page 1 of 14 Airline Name IATA AWB Prefix Country Air Botswana BP 636 Botswana Air Burkina 2J 226 Burkina Faso Air Caledonie TY 190 France Air Caledonie International SB 63 New Caledonia Air Canada AC 14 Canada Air Caribbean XC 918 Neth. -

Punctuality Statistics Economic Regulation Group Aviation Data Unit

Punctuality Statistics Economic Regulation Group Aviation Data Unit Birmingham, Edinburgh, Gatwick, Glasgow, Heathrow, Luton, Manchester, Newcastle, Stansted Full and Summary Analysis December 1996 Disclaimer The information contained in this report will be compiled from various sources and it will not be possible for the CAA to check and verify whether it is accurate and correct nor does the CAA undertake to do so. Consequently the CAA cannot accept any liability for any financial loss caused by the persons reliance on it. Contents Foreword Introductory Notes Full Analysis – By Reporting Airport Birmingham Edinburgh Gatwick Glasgow Heathrow London City Luton Manchester Newcastle Stansted Full Analysis With Arrival / Departure Split – By A Origin / Destination Airport B C – E F – H I – L M – N O – P Q – S T – U V – Z Summary Analysis FOREWORD 1 CONTENT 1.1 Punctuality Statistics: Heathrow, Gatwick, Manchester, Glasgow, Birmingham, Luton, Stansted, Edinburgh, Newcastle and London City - Full and Summary Analysis is prepared by the Civil Aviation Authority with the co-operation of the airport operators and Airport Coordination Ltd. Their assistance is gratefully acknowledged. 2 ENQUIRIES 2.1 Statistics Enquiries concerning the information in this publication and distribution enquiries concerning orders and subscriptions should be addressed to: Civil Aviation Authority Room K4 G3 Aviation Data Unit CAA House 45/59 Kingsway London WC2B 6TE Tel. 020-7453-6258 or 020-7453-6252 or email [email protected] 2.2 Enquiries concerning further analysis of punctuality or other UK civil aviation statistics should be addressed to: Tel: 020-7453-6258 or 020-7453-6252 or email [email protected] Please note that we are unable to publish statistics or provide ad hoc data extracts at lower than monthly aggregate level.