Fire Ecology and Management of the Major Ecosystems of Southern Utah

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Life History and Ecology of the Pinacate Beetle, Eleodes Armatus

The Coleopterists Bulletin, 38(2):150-159. 1984. THE LIFE HISTORY AND ECOLOGY OF THE PINACATE BEETLE, ELEODES ARMA TUS LECONTE (TENEBRIONIDAE) DONALD B. THOMAS U.S. Livestock Insects Laboratory, P.O. Box 232, Kerrville, TX 78028 ABSTRACT Eleodes armatus LeConte, the pinacate beetle, occurs throughout the warm deserts and intermontane valleys of the southwestern United States and northwestern Mexico. It is a scavenger, feeding mainly on plant and animal detritus, and it hides in rodent burrows during times of temperature extremes. Adult activity peaks in the fall but it may occur at any time of the year. Females produce several hundred eggs per season and adults may live for more than 1 year. Larvae are fossorial and require 9 months to develop. The broad ecological, geographical, temporal and dietary range of this beetle may be in part attributable to its defense mechanisms (repugnatorial secretions and allied be- havior) against vertebrate predators. On the black earth on which the ice plants bloomed, hundreds of black stink bugs crawled. And many of them stuck their tails up in the air. "Look at all them stink bugs," Hazel remarked, grateful to the bugs for being there. "They're interesting," said Doc. "Well, what they got their asses up in the air for?" Doc rolled up his wool socks and put them in the rubber boots and from his pocket he brought out dry socks and a pair of thin moccasins. "I don't know why," he said, "I looked them up recently-they're very common animals and one of the commonest things they do is put their tails up in the air. -

Research Paper a Review of Goji Berry (Lycium Barbarum) in Traditional Chinese Medicine As a Promising Organic Superfood And

Academia Journal of Medicinal Plants 6(12): 437-445, December 2018 DOI: 10.15413/ajmp.2018.0186 ISSN: 2315-7720 ©2018 Academia Publishing Research Paper A review of Goji berry (Lycium barbarum) in Traditional Chinese medicine as a promising organic superfood and superfruit in modern industry Accepted 3rd December, 2018 ABSTRACT Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) has been used for thousands of years by different generations in China and other Asian countries as foods to promote good health and as drugs to treat disease. Goji berry (Lycium barbarum), as a Chinese traditional herb and food supplement, contains many nutrients and phytochemicals, such as polysaccharides, scopoletin, the glucosylated precursor, amino acids, flaconoids, carotenoids, vitamins and minerals. It has positive effects on anitcancer, antioxidant activities, retinal function preservation, anti-diabetes, immune function and anti-fatigue. Widely used in traditional Chinese medicine, Goji berries can be sold as a dietary supplement or classified as nutraceutical food due to their long and safe traditional use. Modern Goji pharmacological actions improve function and enhance the body ,s ability to adapt to a variety of noxious stimuli; it significantly inhibits the generation and spread of cancer cells and can improve eyesight and increase reserves of muscle and liver glycogens which may increase human energy and has anti-fatigue effect. Goji berries may improve brain function and enhance learning and memory. It may boost the body ,s adaptive defences, and significantly reduce the levels of serum cholesterol and triglyceride, it may help weight loss and obesity and treats chronic hepatitis and cirrhosis. At Mohamad Hesam Shahrajabian1,2, Wenli present, they are considered functional food with many beneficial effects, which is Sun1,2 and Qi Cheng1,2* why they have become more popular recently, especially in Europe, North America and Australia, as they are considered as superfood with highly nutritive and 1 Biotechnology Research Institute, antioxidant properties. -

M O J a V E D E S E R T I S S U E S a Secondary

MOJAVE DESERT ISSUES A Secondary School Curriculum Bruce W. Bridenbecker & Darleen K. Stoner, Ph.D. Research Assistant Gail Uchwat Mojave Desert Issues was funded with a grant from the National Park �� Foundation. Parks as Classrooms is the educational program of the National ����� �� ���������� Park Service in partnership with the National Park Foundation. Design by Amy Yee and Sandra Kaye Published in 1999 and printed on recycled paper ii iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thanks to the following people for their contribution to this work: Elayn Briggs, Bureau of Land Management Caryn Davidson, National Park Service Larry Ellis, Banning High School Lorenza Fong, National Park Service Veronica Fortun, Bureau of Land Management Corky Hays, National Park Service Lorna Lange-Daggs, National Park Service Dave Martell, Pinon Mesa Middle School David Moore, National Park Service Ruby Newton, National Park Service Carol Peterson, National Park Service Pete Ricards, Twentynine Palms Highschool Kay Rohde, National Park Service Dennis Schramm, National Park Service Jo Simpson, Bureau of Land Management Kirsten Talken, National Park Service Cindy Zacks, Yucca Valley Highschool Joe Zarki, National Park Service The following specialists provided information: John Anderson, California Department of Fish & Game Dave Bieri, National Park Service �� John Crossman, California Department of Parks and Recreation ����� �� ���������� Don Fife, American Land Holders Association Dana Harper, National Park Service Judy Hohman, U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service Becky Miller, California -

Ecoregions of Nevada Ecoregion 5 Is a Mountainous, Deeply Dissected, and Westerly Tilting Fault Block

5 . S i e r r a N e v a d a Ecoregions of Nevada Ecoregion 5 is a mountainous, deeply dissected, and westerly tilting fault block. It is largely composed of granitic rocks that are lithologically distinct from the sedimentary rocks of the Klamath Mountains (78) and the volcanic rocks of the Cascades (4). A Ecoregions denote areas of general similarity in ecosystems and in the type, quality, Vegas, Reno, and Carson City areas. Most of the state is internally drained and lies Literature Cited: high fault scarp divides the Sierra Nevada (5) from the Northern Basin and Range (80) and Central Basin and Range (13) to the 2 2 . A r i z o n a / N e w M e x i c o P l a t e a u east. Near this eastern fault scarp, the Sierra Nevada (5) reaches its highest elevations. Here, moraines, cirques, and small lakes and quantity of environmental resources. They are designed to serve as a spatial within the Great Basin; rivers in the southeast are part of the Colorado River system Bailey, R.G., Avers, P.E., King, T., and McNab, W.H., eds., 1994, Ecoregions and subregions of the Ecoregion 22 is a high dissected plateau underlain by horizontal beds of limestone, sandstone, and shale, cut by canyons, and United States (map): Washington, D.C., USFS, scale 1:7,500,000. are especially common and are products of Pleistocene alpine glaciation. Large areas are above timberline, including Mt. Whitney framework for the research, assessment, management, and monitoring of ecosystems and those in the northeast drain to the Snake River. -

Joshua Tree Species Status Assessment

U.S. FISH & WILDLIFE SERVICE Joshua Tree Species Status Assessment Felicia Sirchia, Scott Hoffmann, and Jennifer Wilkening 10/23/2018 Acknowledgements First and foremost, we would like to thank Tony Mckinney, Carlsbad Fish and Wildlife Office (CFWO) GIS Manager. Tony acquired and summarized data and generated maps for the Species Status Assessment (SSA) – information critical to development of the SSA. Thanks to our Core Team members Jennifer ‘Jena’ Lewinshon, Utah Fish and Wildlife Office, and Brian Wooldridge, Arizona Fish and Wildlife Office. Both these folks were involved early in the SSA development process and provided background on the SSA framework and constructive, helpful feedback on early drafts. Thanks to Bradd Bridges, CFWO Listing and Recovery Chief, and Jenness McBride, Palm Springs Fish and Wildlife Office Division Chief, who provided thorough, helpful comments on early drafts. Thanks to the rest of the Core Team: Arnold Roessler, Region 8, Regional listing Lead; Nancy Ferguson, CFWO; Justin Shoemaker, Region 6; Cheryll Dobson, Region 8 Solicitor; and Jane Hendron, CFWO Public Affairs. All these folks provided constructive, thoughtful comments on drafts of the SSA. Last but not least, we want to thank Wayne Nuckols, CFWO librarian, who provided invaluable research and reference support. Recommended Citation: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2018. Joshua Tree Status Assessment. Dated October 23, 2018. 113 pp. + Appendices A–C. i Table of Contents Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................................... -

ADOT Herbicide Treatment Program on Bureau of Land Management Lands in Arizona

October 2015 BLM DOI-BLM-AZ-0000-2013-0001-EA ADOT Herbicide Treatment Program on Bureau of Land Management Lands in Arizona Final Environmental Assessment Bureau of Land Management Environmental Assessment and Section 4(f) Evaluation ADOT Herbicide Treatment Program on Bureau of Land Management Lands in Arizona DOI-BLM-AZ-0000-2013-0001-EA Bureau of Land Management Arizona State Office One North Central Avenue, Suite 800 Phoenix, Arizona 85004-4427 October 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................. i List of Tables ................................................................................................................................... iii List of Figures .................................................................................................................................. iii Acronym List ................................................................................................................................... iv Section 1 – Proposed Action, Purpose and Need, and Background Information ........................... 1 1.1 Introduction...................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Proposed Action Overview ............................................................................................... 3 1.3 Purpose and Need for Action .......................................................................................... -

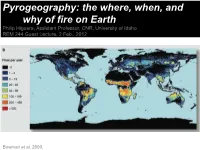

Pyrogeography: the Where, When, and Why of Fire on Earth Philip Higuera, Assistant Professor, CNR, University of Idaho REM 244 Guest Lecture, 2 Feb., 2012

Pyrogeography: the where, when, and why of fire on Earth Philip Higuera, Assistant Professor, CNR, University of Idaho REM 244 Guest Lecture, 2 Feb., 2012 Bowman et al. 2009. Outline for Today’s Class 1. What is pyrogeography? 2. What can you infer from the pattern of fire? 3. Application – How will fire change with climate? What is biogeography? The study of life across space and through time: what do we see, where, and why? The view from Crater Peak, in Washington’s North Cascades 3 Solifluction lobes in Alaska’s Brooks Range Fire boundary in Montana’s Bitter Root Mountains What is pyrogeography? The study of fire across space and through time: what do we see, where, and why? The view from Crater Peak, in Washington’s North Cascades 4 Solifluction lobes in Alaska’s Brooks Range Fire boundary in Montana’s Bitter Root Mountains Fact: Energy released during a fire comes from stored energy in chemical bonds Implication: Fire at all scales is regulated by rates of plant growth University of Idaho Experimental Forest, 2009 What else does fire need to exist? 2006 wildfire, Yukon Flats NWR, Alaska Pyrogeographic framework: “fire” as an organism At multiple scales, the presence of fire depends upon the coincidence of: (1) Consumable resources (2) Atmospheric conditions (3) Ignitions Outline for Today’s Class 1. What is pyrogeography? 2. What can you infer from the pattern of fire? 3. Application – How will fire change with climate? Global patterns of fire – what can we infer? Fires per year (Bowman et al. 2009) . 80-86% of global area burned: grassland and savannas, primarily in Africa, Australia, and South Asia and South America Krawchuk et al., 2009, PLoS ONE: http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0005102 Global patterns of fire – what can we infer? Net primary productivity (Bowman et al. -

Synoptic-Scale Control Over Modern Rainfall and Flood Patterns in the Levant Drylands with Implications for Past Climates

JUNE 2018 ARMONETAL. 1077 Synoptic-Scale Control over Modern Rainfall and Flood Patterns in the Levant Drylands with Implications for Past Climates MOSHE ARMON Fredy and Nadine Herrmann Institute of Earth Sciences, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Givat Ram, Jerusalem, Israel ELAD DENTE Fredy and Nadine Herrmann Institute of Earth Sciences, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Givat Ram, and Geological Survey of Israel, Jerusalem, Israel JAMES A. SMITH Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey YEHOUDA ENZEL AND EFRAT MORIN Fredy and Nadine Herrmann Institute of Earth Sciences, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Givat Ram, Jerusalem, Israel (Manuscript received 23 January 2018, in final form 1 May 2018) ABSTRACT Rainfall in the Levant drylands is scarce but can potentially generate high-magnitude flash floods. Rainstorms are caused by distinct synoptic-scale circulation patterns: Mediterranean cyclone (MC), active Red Sea trough (ARST), and subtropical jet stream (STJ) disturbances, also termed tropical plumes (TPs). The unique spatiotemporal char- acteristics of rainstorms and floods for each circulation pattern were identified. Meteorological reanalyses, quantitative precipitation estimates from weather radars, hydrological data, and indicators of geomorphic changes from remote sensing imagery were used to characterize the chain of hydrometeorological processes leading to distinct flood patterns in the region. Significant differences in the hydrometeorology of these three flood-producing synoptic systems were identified: MC storms draw moisture from the Mediterranean and generate moderate rainfall in the northern part of the region. ARST and TP storms transfer large amounts of moisture from the south, which is converted to rainfall in the hyperarid southernmost parts of the Levant. -

Uranium 2001: Resources, Production and Demand

A Joint Report by the OECD Nuclear Energy Agency and the International Atomic Energy Agency Uranium 2001: Resources, Production and Demand NUCLEAR ENERGY AGENCY ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT Pursuant to Article 1 of the Convention signed in Paris on 14th December 1960, and which came into force on 30th September 1961, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) shall promote policies designed: − to achieve the highest sustainable economic growth and employment and a rising standard of living in Member countries, while maintaining financial stability, and thus to contribute to the development of the world economy; − to contribute to sound economic expansion in Member as well as non-member countries in the process of economic development; and − to contribute to the expansion of world trade on a multilateral, non-discriminatory basis in accordance with international obligations. The original Member countries of the OECD are Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Kingdom and the United States. The following countries became Members subsequently through accession at the dates indicated hereafter: Japan (28th April 1964), Finland (28th January 1969), Australia (7th June 1971), New Zealand (29th May 1973), Mexico (18th May 1994), the Czech Republic (21st December 1995), Hungary (7th May 1996), Poland (22nd November 1996), Korea (12th December 1996) and the Slovak Republic (14 December 2000). The Commission of the European Communities takes part in the work of the OECD (Article 13 of the OECD Convention). -

Habitat Selection of the Desert Night Lizard (Xantusia Vigilis) on Mojave Yucca (Yucca Schidigera) in the Mojave Desert, California

Habitat selection of the desert night lizard (Xantusia vigilis) on Mojave yucca (Yucca schidigera) in the Mojave Desert, California Kirsten Boylan1, Robert Degen2, Carly Sanchez3, Krista Schmidt4, Chantal Sengsourinho5 University of California, San Diego1, University of California, Merced2, University of California, Santa Cruz3, University of California, Davis4 , University of California, San Diego5 ABSTRACT The Mojave Desert is a massive natural ecosystem that acts as a biodiversity hotspot for hundreds of different species. However, there has been little research into many of the organisms that comprise these ecosystems, one being the desert night lizard (Xantusia vigilis). Our study examined the relationship between the common X. vigilis and the Mojave yucca (Yucca schidigera). We investigated whether X. vigilis exhibits habitat preference for fallen Y. schidigera log microhabitats and what factors make certain log microhabitats more suitable for X. vigilis inhabitation. We found that X. vigilis preferred Y. schidigera logs that were larger in circumference and showed no preference for dead or live clonal stands of Y. schidigera. When invertebrates were present, X. vigilis was approximately 50% more likely to also be present. These results suggest that X. vigilis have preferences for different types of Y. schidigera logs and logs where invertebrates are present. These findings are important as they help in understanding one of the Mojave Desert’s most abundant reptile species and the ecosystems of the Mojave Desert as a whole. INTRODUCTION such as the Mojave Desert in California. Habitat selection is an important The Mojave Desert has extreme factor in the shaping of an ecosystem. temperature fluctuations, ranging from Where an animal chooses to live and below freezing to over 134.6 degrees forage can affect distributions of plants, Fahrenheit (Schoenherr 2017). -

IP Athos Renewable Energy Project, Plan of Development, Appendix D.2

APPENDIX D.2 Plant Survey Memorandum Athos Memo Report To: Aspen Environmental Group From: Lehong Chow, Ironwood Consulting, Inc. Date: April 3, 2019 Re: Athos Supplemental Spring 2019 Botanical Surveys This memo report presents the methods and results for supplemental botanical surveys conducted for the Athos Solar Energy Project in March 2019 and supplements the Biological Resources Technical Report (BRTR; Ironwood 2019) which reported on field surveys conducted in 2018. BACKGROUND Botanical surveys were previously conducted in the spring and fall of 2018 for the entirety of the project site for the Athos Solar Energy Project (Athos). However, due to insufficient rain, many plant species did not germinate for proper identification during 2018 spring surveys. Fall surveys in 2018 were conducted only on a reconnaissance-level due to low levels of rain. Regional winter rainfall from the two nearest weather stations showed rainfall averaging at 0.1 inches during botanical surveys conducted in 2018 (Ironwood, 2019). In addition, gen-tie alignments have changed slightly and alternatives, access roads and spur roads have been added. PURPOSE The purpose of this survey was to survey all new additions and re-survey areas of interest including public lands (limited to portions of the gen-tie segments), parcels supporting native vegetation and habitat, and windblown sandy areas where sensitive plant species may occur. The private land parcels in current or former agricultural use were not surveyed (parcel groups A, B, C, E, and part of G). METHODS Survey Areas: The area surveyed for biological resources included the entirety of gen-tie routes (including alternates), spur roads, access roads on public land, parcels supporting native vegetation (parcel groups D and F), and areas covered by windblown sand where sensitive species may occur (portion of parcel group G). -

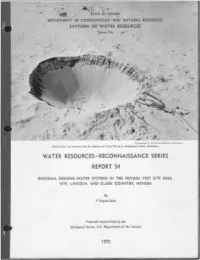

Water Resources-Reconnaissance Series Report 54

STATE OF NEVADA ·DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION AND NATURAL RESOURCES DIVISION OF WATER RESOURCES Carson City / Photograph by Lawrence Radiation Laboratory· Sedan Crater was formed in the dry a ll uv ium of Yucca Flat by on underground atomic detonation. WATER RESOURCES-RECONNAISSANCE SERIES REPORT 54 REGIONAL GROUND-WATER SYSTEMS IN THE NEVADA TEST SITE AREA, NYE, LINCOLN, AND CLARK COUNTIES, NEVADA By F. Eugene Rush Prepared cooperatively by the Geological Survey, U.S. Department of the Interior 1970 WATER RESOURCES - RECONNAISSANCE: SEJUES REPORT 54 ·. REGIONAL GROUND-WATER SYSTEMS·IN THE NEVADA TEST SITE AREA, NYE, LINCOLN, AND CLARK COUN'riE:S, NEVADA By F. Eugene Rush PreparBd cooperatively by the Geological Survey, u.s. Department of the Interior 1971 -\ FOREWORD The progr~m of reconnaissance water-resources studies was authorized by the 1960 Legislature to be carried on by Division of Water Resources of the Departc.ment of· Conservation and Natural Resources in cooperation with the u.s. Geological Survey. This report is the 54th in the series to be prepared by the staff of the Nevada District Office of the U.S. Geological Survey. These 54 reports describe the hydrology of 185 valleys. The reconnaissance surveys make available pertinent information of great and immediate value to many State and Federal agencies, the State cooperating agency, and the public. As development takes place in any area, ,]c,,mands for more detailed information will arise, and studies to supply such information will be undertaken. In the meantime, these reconnaissance studies are timely and adequately In<'eet tlle immediate needs for information on the wate.r resources of the areas covered by the reports.