15 the Polish-Jewish Lethal Polka Dance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

53 Stacja Terenowa Instytutu Biologii Uniwersytetu W Białymstoku Gugny

POLSKIE TERENOWE STACJE GEOGRAFICZNE Nazwa stacji i jej adres Stacja Terenowa Instytutu Biologii Uniwersytetu w Białymstoku Gugny 11 19-104 Trzcianne informacja na stronie internetowej: http://biol-chem.uwb.edu.pl/IP/POL/BIOLOGIA/gugny/gugny.htm Instytucja Uniwersytet w Białymstoku Instytut Biologii ul. Świerkowa 20 B 15-950 Białystok tel. (85) 745 73 02 fax: (85) 745 73 01 kontakt: dr hab. Jan R.E. Taylor, prof. UwB tel. (85) 745 73 21 email: [email protected] mgr Bogusław Lewończuk tel. (85) 745 73 86 email: [email protected] Dojazd – PKP lub PKS do Moniek, lub PKS-em znacznie bliżej – do Trzciannego; dalej (7 km) pieszo lub własnym środkiem transportu do Stacji w Gugnach. Mapa Stacja Terenowa IB UwB w Gugnach 53 INFORMATOR O POLSKICH GEOGRAFICZNYCH STACJACH NAUKOWYCH, BADAWCZYCH I OBSERWACYJNYCH Położenie stacji i charakterystyka obszaru Stacja położona jest we wsi Gugny (gmina Trzcianne), na wschodnim skraju dolnego basenu rzeki Bie- brzy. Basen ten rozciąga się południkowo od Goniądza na północy do ujścia Biebrzy do Narwi na południu i jest efektem akumulacji glacjofluwialnej w czasie topnienia ostatniego terenie lądolodu. Od zachodu dolny basen Biebrzy otaczają stoki Wysoczyzny Kolneńskiej, a od wschodu Wysoczyzny Białostockiej. Na wysokości Gugien dolina Biebrzy ma około 13 km szerokości. Miąższość torfów w basenie dolnym jest mniejsza niż w basenie środkowym i wynosi 1,5 do 2 m. Stacja znajduje się na terenie Biebrzańskiego Parku Narodowego, który chroni największe w Polsce ob- szary bagienne. Nieopodal Stacji, w kierunku zachodnim, rozpościerają się rozległe torfowiska niskie Bagna Podlaskiego, sąsiadującego od południa z Bagnem Ławki. Dużą część Parku zajmują naturalne zbiorowiska roślinne: turzycowiska, mechowiska i szuwary oraz leśne – olsy, brzeziny i bory bagienne. -

UCHWAŁA NR XI/56/11 RADY GMINY TRZCIANNE Z Dnia 29 Września

UCHWAŁA NR XI/56/11 RADY GMINY TRZCIANNE z dnia 29 września 2011 r. w sprawie zmian w budżecie Gminy Trzcianne na 2011 rok Na podstawie art.18 ust. 2 pkt 4 ustawy z dnia 8 marca 1990r. o samorządzie gminnym (Dz.U. z 2001r. Nr 142, poz. 1591, z 2002r. Nr 23, poz. 220,Nr 62, poz. 558, Nr 113, poz. 984, Nr 153, poz. 1271 i Nr 214, poz. 1806, z 2003r. Nr 80, poz. 717 iNr 162, poz. 1568,z 2004r. Nr 102, poz. 1055,Nr 116, poz. 1203,z 2005r. Nr 172, poz.1441iNr 175, poz. 1457,z 2006r. Nr 17, poz. 128iNr 181, poz. 1337,z 2007r. Nr 48, poz. 327,Nr 138, poz. 974iNr 173, poz.1218;z 2008r. Nr 180, poz 1111iNr 223, poz. 1458, z 2009r. Nr 52, poz. 420,Nr 157, poz. 1241,z 2010r. Nr 28, poz. 142i 146,Nr 106, poz 675iNr 40, poz. 230z 2011r. Nr 117, poz. 679 i Nr 21, poz. 113) oraz art. 211 i art. 212 ustawy z dnia 27 sierpnia 2009r. o finansach publicznych (Dz.U. z 2009r. Nr 157, poz. 1240iz 2010r. Nr 28, poz. 146,Nr 123, poz. 835,Nr 152, poz. 1020,Nr 96, poz. 620,Nr 238 poz. 1578iNr 257, poz. 1726) uchwala się, co następuje: § 1. Dokonuje się zmian w budżecie Gminy Trzcianne polegających na: 1. Zmianie planu dochodów budżetowych, poprzez zwiększenie planu dochodów budżetowych o kwotę 23 405 zł. zgodnie z załącznikiem Nr 1. 2. Zmianie planu wydatków budżetowych, poprzez zwiększenie planu wydatków o kwotę 44 498 zł oraz zmniejszenie planu wydatków o kwotę 21 093 zł zgodnie z załącznikiem Nr 2. -

The Role of Shared Historical Memory in Israeli and Polish Education Systems. Issues and Trends

Zeszyty Naukowe Wyższej Szkoły Humanitas. Pedagogika, ss. 273-293 Oryginalny artykuł naukowy Original article Data wpływu/Received: 16.02.2019 Data recenzji/Accepted: 26.04.2019 Data publikacji/Published: 10.06.2019 Źródła finansowania publikacji: Ariel University DOI: 10.5604/01.3001.0013.2311 Authors’ Contribution: (A) Study Design (projekt badania) (B) Data Collection (zbieranie danych) (C) Statistical Analysis (analiza statystyczna) (D) Data Interpretation (interpretacja danych) (E) Manuscript Preparation (redagowanie opracowania) (F) Literature Search (badania literaturowe) Nitza Davidovitch* Eyal Levin** THE ROLE OF SHARED HISTORICAL MEMORY IN ISRAELI AND POLISH EDUCATION SYSTEMS. ISSUES AND TRENDS INTRODUCTION n February 1, 2018, despite Israeli and American criticism, Poland’s Sen- Oate approved a highly controversial bill that bans any Holocaust accusations against Poles as well as descriptions of Nazi death camps as Polish. The law essentially bans accusations that some Poles were complicit in the Nazi crimes committed on Polish soil, including the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp. Once the leg- islation was signed into law, about a fortnight later, by Polish President Andrzej Duda, anyone convicted under the law could face fines or up to three years in jail. Critics of the bill, including the US State Department and Israeli officials, feared that it would infringe upon free speech and could even be used to target Holocaust survivors or historians. In Israel, the reaction was fierce. “One cannot change history, * ORCID: 0000-0001-7273-903X. Ariel University in Izrael. ** ORCID: 0000-0001-5461-6634. Ariel University in Izrael. ZN_20_2019_POL.indb 273 05.06.2019 14:08:14 274 Nitza Davidovitch, Eyal Levin and the Holocaust cannot be denied,” Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu stated. -

The Judgment of “Privileged” Jews in the Work of Raul Hilberg R

CHAPTER 2 THE JUDGMENT OF “PRIVILEGED” JEWS IN THE WORK OF RAUL HILBERG R To a Jew this role of the Jewish leaders in the destruction of their own peo- ple is undoubtedly the darkest chapter of the whole dark story. It had been known about before, but it has now been exposed for the fi rst time in all its pathetic and sordid detail by Raul Hilberg. —Hannah Arendt, Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil The limit of judgment in relation to “privileged” Jews is crucially im- portant to a consideration of Hilberg’s work, the widespread impact of which cannot be underestimated. His seminal study, The Destruction of the European Jews, has been praised by many as “the single most important work on the Holocaust,” and Hilberg himself has been char- acterized as “the single most important historian” in the fi eld.1 Fur- thermore, the above epigraph makes clear that Arendt’s controversial arguments regarding Jewish leaders (see the introduction) drew heav- ily on Hilberg’s pioneering work. This chapter investigates the part of Hilberg’s work that deals with “privileged” Jews, in order to provide a thematic analysis of the means by which Hilberg passes his overwhelm- ingly negative judgments on this group of Holocaust victims. Hilberg’s judgments are conveyed in diverse ways due to the eclec - tic nature of his publications, in which the subject of the Judenräte— which has received considerable attention in Holocaust historiography— This open access library edition is supported by Knowledge Unlatched. Not for resale. The Judgment of “Privileged” Jews in the Work of Raul Hilberg 77 makes frequent appearances. -

1 University of Haifa Weiss-Livnat International MA Program in Holocaust Studies Online Course: the Extermination of Polish

University of Haifa Weiss-Livnat International MA Program in Holocaust Studies Online course: The Extermination of Polish Jews, 1939-1945 Prof. Jan Grabowski [email protected] In 1939, there were 3.3 million Jews in Poland, or about 10% of the total population of the Polish Republic. Polish Jews formed the largest Jewish community in Europe. In 1945, six years later, no more than 50,000 Jews remained alive in Poland. Almost 98.5% of Polish Jewry (excluding the 300.000 who fled the Germans and survived in the Soviet Union) have perished in the Holocaust. A nation rich in history, with its own traditions and language ceased to exist. On September 1st, 1939, the German forces invaded Poland and – before the end of the month – completed the conquest of the country. The course will focus on the initial German policies directed against the Jews and, at the same time, it shall follow the reactions of the Jewish community in the face of new existential threats. The lectures will shed light on the creation of the ghettos, on the strategy of the Jewish leadership and on the plight of the Jewish masses. The course will explore the growing German terror and the implementation of the “Final Solution of the Jewish Question”- as Germans referred to the policies of mass extermination. The students will become familiar with the planning and the execution of the so-called “Aktion Reinhard”, as well as with the survival strategies pursued later by the Jews who avoided the 1942-43 deportations to the extermination camps. While learning about German perpetrators and Jewish victims, the students will also explore the attitudes of the Polish society and the Polish Catholic Church to the persecuted Jews. -

Dominik Flisiak PARTICIPATION of JEWS in the KOŚCIUSZKO

STUDIA HUMANISTYCZNO-SPOŁECZNE (HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL STUDIES) 14 Edited by Radosław Kubicki and Wojciech Saletra 2016 Dominik Flisiak Jan Kochanowski University in Kielce, Poland PARTICIPATION OF JEWS IN THE KOŚCIUSZKO UPRISING. THE MEMORY OF POLISH AND JEWISH BROTHERHOOD OF ARMS At the end of the second half of the 18th century, about 750–800 thousand Jews lived in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.1 That constituted approximately 6% of the overall population. A significant number of Orthodox Jews lived in quahals, Jewish Communities. About 66% of them lived in towns, the rest lived in villages.2 A major part of that society worked as traders, innkeepers, or craftsmen. Only a small percentage worked as farmers.3 The majority of Jews living in Poland strictly adhered to the principles set in the Old Testament and Talmud. There was an idea to assimilate worshippers of Judaism into the Polish culture. Enthusiasts of this idea were, among others, Eliasz Accord and Mendel Lefin.4 In their plan, they referred to the concept of "maskils", followers of Moses Mendelssohn, the creator of haskalah, i.e. the Jewish enlightenment. Worshippers of Judaism did not serve in the army of the Crown and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.5 It resulted from i.a. religious differences and the common opinion that worshippers of Judaism were cowards.6 What is more, some radical Jews warned their fellow worshippers against any military service, which they found a breach of religious principles.7 However, during armed conflicts representa- tives of that minority were obligated to participate in defending cities and supplying 1 Historia Żydów Polskich, „Polityka”, wydanie specjalne. -

Harmonogram Gmina Trzcianne 2021

Terminy Odbiorów 2021 roku Miejscowo ść Miesi ąc Odpady Odpady Odpady Popiół zmieszane Segregowane BIO Dzie ń Dzie ń Dzie ń Dzie ń Stycze ń 8 28 28 - Luty 5 23 23 25 Trzcianne, Kolonia Zucielec Marzec 5 24 24 - Zbiórka odpadów Kwiecie ń 6,20 27 10,27 29 wielkogabarytowych np. stare Maj 10,24 18 7,18 - meble, wersalki, dywany itp., sprz ęt elektroniczny i elektryczny ( Czerwiec 8,22 17 4,17 kompletny) np. lodówki, pralki, Lipiec 7,21 15 1,15 komputery, odkurzacze itp. b ędą Sierpie ń 6,23 16 2,16 zbierane 22 marca 2021; ś 29 wrze nia 2021. Jednocze śnie Wrzesie ń 7,21 15 1,15 zwracamy uwag ę, i ż zbiórka odbywa si ę od godz. 7.00 ( sprz ęty Pa ździernik 7,21 15 1,15 19 wystawione pó źniej nie b ędą Listopad 5 16 16 zabrane). Prosimy o wystawienie Grudzie ń 6 14 14 30 w/w odpadów przed posesjami w sposób nieutrudniaj ący przejazdu. Terminy Odbiorów 2021 roku Miejscowo ść Miesi ąc Odpady Odpady Odpady Popiół Zmieszane segregowane BIO Dzie ń Dzie ń Dzie ń Stycze ń 11 28 28 Zubole, Boguszewo, Luty 8 23 23 25 kolonia Nowa Wie ś Marzec 8 24 24 - Zbiórka odpadów Kwiecie ń 11,25 27 10,27 29 wielkogabarytowych np. stare Maj 5,19 18 7,18 - meble, wersalki, dywany itp., sprz ęt elektroniczny i elektryczny ( Czerwiec 9,23 17 4,17 kompletny) np. lodówki, pralki, Lipiec 8,22 15 1,15 komputery, odkurzacze itp. b ędą Sierpie ń 9,24 16 2,16 zbierane 22 marca 2021; 29 wrze śnia 2021. -

How the Jewish Police in the Kovno Ghetto Saw Itself by Dov Levin

How the Jewish Police in the Kovno Ghetto Saw Itself by Dov Levin This article represents the first English-language publication of selections from a unique document written in Yiddish by the Jewish police of the Kovno (Kaunas) ghetto in Lithuania. The introduction describes briefly the history of the Kovno ghetto and sheds light on the document’s main elements; above all, those involving the Jewish police in the ghetto. As the historiography of the Holocaust includes extensive research, eyewitness accounts, photographs, and documents of all kinds, this introduction is intended to provide background material only, as an aid in the reading of the following excerpts. The document was composed over many months at the height of the Holocaust period in the Kovno ghetto. It focuses primarily on the key sector of the ghetto’s internal authority – the Jewish police. The official name of the police was Jüdische Ghetto-Polizei in Wiliampole (“Jewish Ghetto Police in Vilijampole”), and, in the nature of things, since the Holocaust, this body has become practically synonymous with collaboration with the occupying forces. Ostensibly a chronicle of police activities during the ghetto period, the document in fact reflects an attempt by the Jewish police at self-examination and substantive commentary as the events unfolded. The History of the Ghetto1 On June 24, 1941, the third day of the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany, Kovno (Kaunas), Lithuania’s second largest city, famed as an important cultural and spiritual center, was occupied. Kovno had a distinguished name in the Jewish world primarily because of the Knesset 1 The primary sources for this chapter are: Leib Garfunkel, The Destruction of Kovno’s Jewry (Hebrew) (Jerusalem: Yad Vashem, 1959); Josef Gar, The Destruction of Jewish Kovno (Yiddish) (Munich: Association of Lithuanian Jews in the American Zone in Germany, 1948); Josef Rosin, “Kovno,” Pinkas Hakehillot: Encyclopedia of Jewish Communities – Lithuania (Hebrew), Dov Levin, ed. -

Gazeta Volume 28, No. 1 Winter 2021

Volume 28, No. 1 Gazeta Winter 2021 Orchestra from an orphanage led by Janusz Korczak (pictured center) and Stefania Wilczyńska. Warsaw, 1923. Courtesy of the Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute. Used with permission A quarterly publication of the American Association for Polish-Jewish Studies and Taube Foundation for Jewish Life & Culture Editorial & Design: Tressa Berman, Daniel Blokh, Fay Bussgang, Julian Bussgang, Shana Penn, Antony Polonsky, Aleksandra Sajdak, William Zeisel, LaserCom Design, and Taube Center for Jewish Life and Learning. CONTENTS Message from Irene Pipes ............................................................................................... 4 Message from Tad Taube and Shana Penn ................................................................... 5 FEATURE ARTICLES Paweł Śpiewak: “Do Not Close the Experience in a Time Capsule” ............................ 6 From Behind the Camera: Polish Jewish Narratives Agnieszka Holland and Roberta Grossman in Conversation ................................... 11 EXHIBITIONS When Memory Speaks: Ten Polish Cities/Ten Jewish Stories at the Galicia Jewish Museum Edward Serrota .................................................................................................................... 15 Traces of Memory in Japan ............................................................................................ 19 Where Art Thou? Gen 3:9 at the Jewish Historical Institute ........................................ 20 REPORTS Libel Action Against Barbara Engelking -

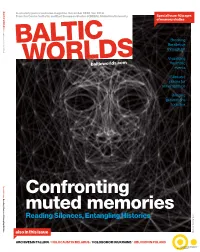

Confronting Muted Memories Reading Silences, Entangling Histories

BALTIC WORLDSBALTIC A scholarly journal and news magazine. December 2020. Vol. XIII:4. From the Centre for Baltic and East European Studies (CBEES), Södertörn University. Special Issue: 92 pages of memory studies December 2020. Vol. XIII:4 XIII:4 Vol. 2020. December Breaking BALTIC the silence through art Visualizing WORLDSbalticworlds.com traumatic events Sites and places for remembrance Bringing generations together Special issue: issue: Special Confronting Reading Silences, Entangling Histries Entangling Silences, Reading muted memories Reading Silences, Entangling Histories also in this issue Sunvisson Karin Illustration: ARCHIVES IN TALLINN / HOLOCAUST IN BELARUS / HOLODOMOR IN UKRAINE/ OBLIVION IN POLAND Sponsored by the Foundation BALTIC for Baltic and East European Studies WORLDSbalticworlds.com editorial in this issue Dealing with the demons of the past here are many aspects of the past even after generations. An in- that we talk little about, if at all. The dividual take is often the case, dark past casts shadows and when and the own family history is silenced for a long time, it will not drawn into this exploring artistic Tleave the bearer at peace. Nations, minorities, process. By facing the demons of families, and individuals suffer the trauma of the past through art, we may be the past over generations. The untold doesn’t able to create new conversations go away and can even tear us apart if not dealt and learn about our history with Visual with. Those are the topics explored in this Spe- less fear and prejudice, runs the representation cial Issue of Baltic Worlds “Reading Silences, argument. Film-makers, artists Entangling Histories”, guest edited by Margaret and researchers share their un- of the Holodomor Tali and Ieva Astahovska. -

Andrzej Chojnacki – Studium Nad Operacyjnym Wykorzystaniem Międzyrzecza Wisły, Bugu I Wieprza W Dobie Wojen Napoleońskich (1795–1813) 119

OŚRODEK BADAŃ HISTORII WOJSKOWEJ MUZEUM WOJSKA W BIAŁYMSTOKU STUDIA Z DZIEJÓW WOJSKOWOŚCI TOM VII BIAŁYSTOK 2018 Rada Naukowa „Studiów z Dziejów Wojskowości” Prof. dr hab. Zbigniew Anusik, prof. dr hab. Wiesław Caban, prof. dr hab. Czesław K. Grzelak, prof. dr hab. Norbert Kasparek, prof. dr hab. Jerzy Maroń, prof. dr hab. Zygmunt Matuszak, prof. dr hab. Grzegorz Nowik, prof. dr hab. Marek Plewczyński, prof. dr hab. Andrzej Rachuba, prof. dr hab. Wal- demar Rezmer, prof. dr hab. Wanda Krystyna Roman, prof. dr hab. Witold Świętosławski, płk dr hab. Juliusz S. Tym, prof. dr hab. Henryk Wisner, prof. dr hab. Wojciech Włodarkiewicz Kolegium redakcyjne: Prof. dr hab. Karol Olejnik – redaktor naczelny Dr hab. Adam Dobroński – zastępca redaktora Dr Tomasz Wesołowski – sekretarz redakcji Mgr Natalia Filinowicz – członek redakcji Mgr Łukasz Radulski – członek redakcji Recenzentci naukowi: dr hab. Sławomir Augusiewicz, dr hab. Aleksander Bołdyrew, dr hab. Tomasz Ciesielski, dr hab. Maciej Franz, dr hab. Tadeusz Grabarczyk, dr hab. Witold Jarno, dr hab. Jacek Legieć, prof. dr hab. Mirosław Lenart, dr hab. Robert Jerzy Majzner, dr hab. Andrzej Niewiński, prof. dr hab. Janusz Odziemkowski, dr hab. Adam Perłakowski, dr hab. Zbigniew Pilarczyk, dr hab. Jan Ptak, prof. dr hab. Aleksander Smoliński, dr hab. Tomasz Strzeżek, dr hab. Jacek Szczepański, płk prof. dr hab Janusz Zuziak, dr hab. Tadeusz Zych Tom powstał przy współpracy Zespołu Historii Wojskowości Komitetu Nauk Historycznych Polskiej Akademii Nauk ISSN 2299-3916 Korekta językowa: Judyta Grabowska Przekład streszczeń na język angielski i rosyjski – Agencja Tłumaczeń ABEO Adres redakcji: Ośrodek Badań Historii Wojskowej Muzeum Wojska w Białymstoku ul. Jana Kilińskiego 7 15-089 Białystok tel. -

Podlaska Wieś CHOJNOWO Szkic Historyczny

Józef Maroszek, Arkadiusz Studniarek Podlaska wieś CHOJNOWO Szkic historyczny Białystok 2007 1 © Copyright by: Józef Maroszek, Arkadiusz Studniarek, 2007 r. „Towarzystwo Miłośników Ziemi Trzciańskiej”, 2007 r. Autorzy dr hab. prof. UwB Józef Maroszek mgr Arkadiusz Studniarek Autor części „Chojnowo w 2007 roku” i patron wydania Zdzisław Dąbrowski Fotografie Zdzisław Dąbrowski, Piotr Romanowski, Arkadiusz Studniarek, Tomasz Tuszyński, zbiory prywatne Redakcja Justyna Romanowska Korekta Ewa Rogucka Skład e-Print Michał Żelezniakowicz Wydawca PRO100 Agencja Reklamowa na zlecenie „Towarzystwa Miłośników Ziemi Trzciańskiej” Druk i oprawa PRO100 Agencja Reklamowa /LOGO/ ISBN: ????? SPONSORZY WYDANIA: Virginia Hotchkiss – USA Bank Ochrony Środowiska w Warszawie Przedsiębiorstwo Usługowo-Handlowe „MPO” Sp. z o.o. w Białymstoku Obróbka Metali i Przetwarzania Tworzyw Sztucznych „METALERG” w Oławie PHU Adam Chwatko Stacja Kontroli Pojazdów w Trzciannem 2 3 4 Szanowni Państwo, Z największą przyjemnością oddajemy w Państwa ręce drugą z publi- kacji poświęconych ziemi Trzciańskiej – pierwszym tytułem w tym projek- cie była monografia wsi Wyszowate. Zamysł cyklu książek pod wspólnym tytułem „Podlaska wieś” powstał z inicjatywy Towarzystwa Miłośników Ziemi Trzciańskiej, którego funkcję prezesa mam zaszczyt pełnić od 1998 r. Celem Towarzystwa jest kultywowanie tradycji naszej „małej ojczyzny” oraz odkrywanie i przybliżanie jej historii. Dzieje wsi Chojnowo to monografia, na którą składają się wyniki ba- dań historycznych prof. Józefa Maroszka i