A Case-Study of the Rythu Bandhu Scheme (RBS) in Telangana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

7026/SIC-KSR/2019 Dated: 12-06-2020

TELANGANA STATE INFORMATION COMMISSION (Under Right to Information Act, 2005) Samachara Hakku Bhavan, D.No.5-4-399, ‘4’ Storied Commercial Complex, Housing Board Building, Mojam Jahi Market, Hyderabad – 500 001. Phone Nos: 040-24740665 (o); 040-24740592(f) Appeal No.7026/SIC-KSR/2019 Dated: 12-06-2020 Appellant : Sri G. Narendar, Warangal Urban District Respondents : The Public Information Officer (U/RTI Act, 2005) / O/o. The Tahsildar, Mandal Revenue Office, Venkatapur Mandal, Mulugu District The Appellate Authority (U/RTI Act, 2005) / O/o. The Revenue Divisional Officer, Mulugu Division, Mulugu District. O R D E R Sri G. Narendar, Warangal Urban District has filed 2nd appeal dated 19-06-2019 which was received by this Commission on 21-06-2019 for not getting the information sought by him from the PIO / O/o. The Tahsildar, Mandal Revenue Office, Venkatapur Mandal, Mulugu District and 1st Appellate Authority / O/o. The Revenue Divisional Officer, Mulugu Division, Mulugu District. The brief facts of the case as per the appeal and other records received along with it are that the appellant herein filed an application dated 28-03-2019 before the PIO under Sec.6(1) of the RTI Act, 2005, requesting to furnish the information on the following points mentioned in his application: TSIC The Public Information Officer/O/o. The Tahsildar, Venkatapur Mandal, Mulugu District has furnished part information to the Revenue Divisional Officer, Mulugu Division vide letter No.254/2019 dated 25-06-2019 which was received by the appellant. Since the appellant was not satisfied with the reply received from the Public Information Officer, he filed 1st appeal dated 04-05-2019 before the 1st Appellate Authority U/s 19(1) of the RTI Act, 2005 requesting him to furnish the information sought by him. -

TELANGANA STATE ELECTRICITY REGULATORY COMMISSION 11-4-660, 5Th Floor, Singareni Bhavan, Red Hills, Hyderabad

TELANGANA STATE ELECTRICITY REGULATORY COMMISSION 11-4-660, 5th Floor, Singareni Bhavan, Red Hills, Hyderabad. Phone Nos. (040) 23397625/ 23311125 to 28 Fax No. (040) 23397489 Website www.tserc.gov.in PUBLIC NOTICE O. P. No. 12 of 2020 In the matter of according approval for further amending the distribution and retail supply licence granted earlier to M/s. Northern Power Distribution Company of Telangana Limited (TSNPDCL) and also to permit taking over of assets falling under the additional area of operation from M/s. Southern Power Distribution Company of Telangana Limited (TSSPDCL). Whereas the Telangana State Electricity Regulatory Commission (TSERC) has granted license (License No. 14 of 2000) on 29.12.2000 under Section 15 of the Telangana Electricity Reform Act, 1998 (State Act No. 30 of 1998) to the Northern Power Distribution Company of Andhra Pradesh Limited (APNPDCL), for carrying on the business of distribution and retail supply of electricity within the area of supply of Warangal, Khammam, Karimnagar, Nizamabad and Adilabad Districts for a period of 30 years. And whereas, consequent to the bifurcation of the state on 02.06.2014 and pursuant to government order vide G. O. Ms. Nos. 221 to 235 dated 11.10.2016 in respect of Formation / Reorganization of Districts, Revenue Divisions and Mandals in the Telangana state issued by the Government of Telangana (GoTS), the Commission considering the request of the licensee and noticing that there is no opposition to the amendment of the licence, has modified the Licence No. 14 of 2000 on the file of TSERC by order dated 17.03.2017. -

List of Notified Sezs

List of Notified SEZs. S.No Name of the Developer Location Type State Area Date of Notification code (hectares) ANDHRA PRADESH 1 Divi’s Labo Chippada Village, Pharmaceuticals AP 105.496/9.29/1 16th May 2006/ 18th Limited Visakhapatnam, Andhra 7.857 (Total June, 2010/ 26th Pradesh 132.643) July, 2011 2 Apache SEZ Mandal Tada, Nellore Footwear AP 126/de-notified 8th Aug 2006/ 6th Development India District, Andhra Pradesh 22.82 (Total August, 2010 Private Limited 104.08) 3 Whitefield Paper Mills Tallapudi Mandal, West Writing and AP 109.81 22th Dec 2006 Ltd. Godavari District, Andhra printing paper mill Pradesh 4 Andhra Pradesh Industrial Madhurawada Village, IT/ITES AP 36 28th Dec 2006 Infrastructure Corporation Visakhapatnam Rural Limited (APIIC) Mandal, Andhra Pradesh 5 Hetero Infrastructure Pvt. Nakkapalli Mandal, Pharmaceuticals AP 100.28 11th Jan 2007 Ltd. Visakhapatnam District, Andhra Pradesh 6 L&T Hitech City Limited Keesarapalli Village, ITES AP 12(de-notified 15th Jan 2007/ (formerly, Andhra Gannavaram Mandal, of 2) Total 10 5th October, 2011 Pradesh Industrial Krishna District, Andhra Infrastructural Pradesh Corporation Ltd.(APIIC) 7 Brandix India Apparel Duppituru, Doturupalem Textile AP 404.70 10th April 2007 City Private Limited Maruture and Gurujaplen Villages in Visakhapatnam District, Andhra Pradesh 8 Andhra Pradesh Industrial Madhurawada Village, IT/ITES AP 16 11th April 2007 Infrastructural Visakhapatnam District, Corporation Ltd.(APIIC) Andhra Pradesh 9 Andhra Pradesh Industrial Atchutapuram and Multi-Product AP 2264 12th April 2007 Infrastructural Rambilli Mandals, Corporation Ltd.(APIIC) Visakhapatnam District, Andhra Pradesh 10 Kakinada SEZ Private Ramanakkapeta and A. V. Multi-product AP 1035.6688 23th April 2007 Limited Nagaram Vikllages, East Godavari District, Kakinada, Andhra Pradesh 11 Ramky Pharma City E-Bonangi Villages, Pharmaceuticals AP 247.39 10th May 2007 (India) Pvt. -

Dt: 25-07-2019. Tender Notice for Job Work at Godowns

THE COTTON CORPORATION OF INDIA LTD. (A Government of India Undertaking) BRANCH OFFICE:2ND& 3RD Floor, V.L.Chittimalla Complex, H.No.16- 07-109, Laxmipuram, Near Old Grain Market, Warangal – 506002 (T.S.) CIN: U51490MH1970GO1014733 Phone No.0870 – 2565088, 2429394, Fax No.0870-2501451 Website: www.cotcorp.gov.in. E-Mail: [email protected] Ministry web: www.texmin.nic.in REF: CCI/MKTG (GODOWNS)/2019-20/ DT: 25-07-2019. TENDER NOTICE FOR JOB WORK AT GODOWNS The Cotton Corporation of India Ltd., Branch Office Warangal invites sealed Tenders from reputed Job Work Contractors for handling various works relating to Fully Pressed Cotton Bales like Carrying, Stacking, De-stacking, Weighment, Sample cutting etc and for handling the miscellaneous items like Tarpaulins, Grey cloth, Jute Twine and Lint boundaries in various godowns located under various Districts of Warangal Urban, Warangal Rural, Jangaon, Mehabubabad, Jayashankar Bhupalapally, Mulugu, Rajanna Sircilla, Jagityala, Peddapally, Suryapet, Siddipet, Khammam, Karimnagar, Sangareddy, Medak, Bhadradri Kothagudem etc.inTelangana State. Tender form can be downloaded from the website and the tenderers shall have to pay Rs.112/- including GST by DD drawn in favour of The Cotton Corporation of India Ltd., Warangal, payable at Warangal Tender form duly completed in all aspects along with EMD of Rs. 20000/- for each godowns separately as per the godown list should be submitted only in sealed cover super scribed as “Tender for Job Work Contract in Godowns for cotton season 2019-20.” addressed to the Dy. General Manager, should reach to the above address on or before 02.30 P.M on 13- 08-2019 The sealed tenders received within the stipulated time shall be opened on the same day i.e. -

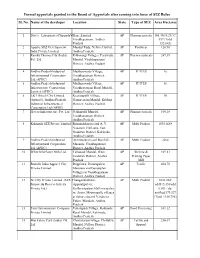

Formal Approvals Granted in the Board of Approvals After Coming Into Force of SEZ Rules

Formal approvals granted in the Board of Approvals after coming into force of SEZ Rules Sl. No. Name of the developer Location State Type of SEZ Area Hectares 1 Divi’s LaboratoriesChippadaVillage,Limited AP Pharmaceuticals 105.496/9.29/17. Visakhapatnam, Andhra 857 (Total Pradesh 132.643) 2 Apache SEZ Development Mandal Tada, Nellore District, AP Footwear 126.90 India Private Limited Andhra Pradesh 3 Ramky Pharma City (India) E-Bonangi Villages, Parawada AP Pharmaceuitacals 247.39 Pvt. Ltd. Mandal, Visakhapatnam District, Andhra Pradesh 4 Andhra Pradesh Industrial Madhurawada Village, AP IT/ITES 16 Infrastructural Corporation Visakhapatnam District, Ltd.(APIIC) Andhra Pradesh 5 Andhra Pradesh Industrial Madhurawada Village, AP IT/ITES 36 Infrastructure Corporation Visakhapatnam Rural Mandal, Limited (APIIC) Andhra Pradesh 6 L&T Hitech City Limited Keesarapalli Village, AP IT/ITES 10 (formerly, Andhra Pradesh Gannavaram Mandal, Krishna Industrial Infrastructural District, Andhra Pradesh Corporation Ltd.(APIIC) 7 Hetero Infrastructure Pvt. Ltd. Nakkapalli Mandal, AP Pharmaceuticals 100.28 Visakhapatnam District, Andhra Pradesh 8 Kakinada SEZ Private Limited Ramanakkapeta and A. V. AP Multi Product 1035.6688 Nagaram Vikllages, East Godavari District, Kakinada, Andhra Pradesh 9 Andhra Pradesh Industrial Atchutapuram and Rambilli AP Multi Product 2264 Infrastructural Corporation Mandals, Visakhapatnam Ltd.(APIIC) District, Andhra Pradesh 10 Whitefield Paper Mills Ltd. Tallapudi Mandal, West AP Writing & 109.81 Godavari District, Andhra Printing -

Current Affairs - Monthly Edition PDF (February 1 - February 28, 2019)

.com Current Affairs - Monthly Edition PDF (February 1 - February 28, 2019) Table of Contents 1. BANKING & FINANCE 4 2. BUSINESS & ECONOMY 10 3. INTERNATIONAL 18 4. INDIAN AFFAIRS 32 5. SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY 78 6. ENVIRONMENT 88 7. BILLS & ACTS 91 8. DEFENCE 94 9. AWARDS AND HONOURS 99 10. SPORTS 106 11. ARTS & CULTURE 113 12. OBITUARY 114 13. SUMMITS & CONFERENCE 115 14. SCHEMES 116 15. APPOINTMENTS / RESIGN 119 16. IMPORTANT DAYS 126 17. AGREEMENTS, MOU 128 18. BUDGET / TAXES 132 19. VISITS BY PM / PRESIDENT 135 20. QUIZ CORNER 137 21. USEFUL LINKS 145 .com Current Affairs - Monthly Edition PDF (February 1 - February 28, 2019) BANKING & FINANCE RBI lifted its curb on 3 banks under PCA framework The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has decided to allow three public sector banks, Bank of India, Bank of Maharashtra and Oriental Bank of Commerce, to exit the PCA framework following capital infusion by the government and a decline in net non-performing asset (NPA) ratio. RBI, which conducted a review following a demand made by the government to lift the restrictions in order to boost credit growth. RBI said that few banks are not in breach of the PCA (Prompt Corrective Action) parameters as per their published results for the quarter ending December 2018, except for return on assets (RoA). However, though the RoA continues to be negative, the same is reflected in the capital adequacy indicator. The PCA framework is triggered when a bank breaches one of the three risk thresholds, and crossing 6% net NPAs is one of them. -

TRS Sweeps Civic Body Chief Polls

c m y k c m y k THE LARGEST CIRCULATED ENGLISH DAILY IN SOUTH INDIA HYDERABAD I TUESDAY I 28 JANUARY 2020 WEATHER O WORLD 9 TABLOID Max: 33.5 C | SPORTS 14 Min: 17OC | RH: 38% Billie Eilish bags Basketball star Bryant Something sweet, Rainfall: Nil top 4 Grammies dies in chopper crash something hot Forecast: Partly cloudy sky. Misty morning. Max/Min temp. 33/17ºC deccanchronicle.com, facebook.com/deccannews, twitter.com/deccanchronicle, google.com/+deccanchronicle Vol. 83 No. 27 Established 1938 | 32 PAGES | `6.00 ASTROGUIDE WB ASSEMBLY Vikari; Uttarayana Tithi: Magha Shuddha Tadiya till 4 more in isolation ward REJECTS CAA TRS sweeps civic 8.22 am Star: Shatabisham till 9.23 am AFTER 3 STATES Varjyam: 4.32 pm to 6.19 pm for coronavirus testing Durmuhurtam: 9.07 am to RAJIB CHOWDHURI | DC 9.51 am; 11.12 pm to 12.03 am KOLKATA, JAN. 27 body chief polls Rahukalam: 3 pm to 4.30 pm Samples stuck in city for lack of funding HIJRI CALENDAR The West Bengal on Jumada al-Thani 2,1441 AH KANIZA GARARI | DC iNSIDE tainer and those handling Monday became the fourth Wins 109 out of 120 municipal chief positions PRAYERS HYDERABAD, JAN. 27 it have to wear gloves and state in the country after Fajar: 5.46 am ■ Page 7: Thai national masks. The samples have Kerala, Punjab and S.A. ISHAQUI | DC Zohar: 12.39 pm A scientist who arrived dies in WB, coronavirus to be sent in a private Rajasthan to have passed HYDERABAD, JAN. -

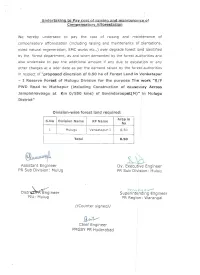

Distr~Ineer Superintending Engineer PIU: Mulug PR Region: Warangal

Undertaking t o Pay cost of raising and maintenance of Compensatory Afforestation ' We hereby undertake to pay the cost of raising and maintenance of compensatory afforestation (including raising and maintenance of plantations, I aided natural regeneration, SMC works etc.,) over degrade forest land identified , by the forest department, as and when demanded by the forest authorities and I also undertake to pay the additional amount if any due to escalation or any other charges at a later date as per the demand raised by the forest! authorities in respect of "proposed diversion of 0.50 ha of Forest Land in Venkatapur - I Reserve Forest of Mulugu Division for the purpose The work "R/ F PWD Road to Muthapur (including Construction of causeway Across Jampannavaagu at Km 0/550 kms) of Govindaraopet(M)" in Mulugu District" Division-wise forest land required: Area in S.No Division Name RF Name ha 1 Mulugu Venkatapur-I 0 . 50 Total 0.50 ~ bJO/ Assistant Engineer Oy. Executive Engineer PR Sub Division: Mu lug PR Sub Division: Mulug ~a:>-\ ~-r- Distr~ineer Superintending Engineer PIU: Mulug PR Region: Warangal //COLJnter signed// ~v- Chief Engineer PMGSY PR Hyderabad Undertaking for unqualified commitm ent from project authority to Pay cost of extraction of tree growth We hereby undertake to pay the cost of exploitation of tree grbwth of the ! forest land proposed for diversion under the project as and when deimanded by I the forest authorities and also undertake to pay the additional amount if any due to escalation or any other charges at a later date as per the demanid raised by the forest authorities in respect of in respect "proposed diversion IOf 0.50 ha of Forest Land in Venkatapur - I Reserve Forest of Mulugu Division for the purpose The work "R/F PWD Road to Muthapur ( including Construction of causeway Across Ja m pannavaagu at Km O/ S~ O kms) of Govindaraopet(M)" in Mulug u District" Division-wise forest land required: Are a in S.No Division Name RF Name ha 1 Mulugu Venkatapur-I 0.50 Total 0 .50 A ~eer Dy. -

List of Students Leraner Centres Offering Ug & Pg Courses For

LIST OF STUDENTS LERANER CENTRES OFFERING UG & PG COURSES FOR ACADEMIC YEAR 2020-21 Sl. No. WARANGAL URBAN DISTRICT Mobile No 1. SDLCE, Kakatiya University, Warangal 0870-2438899 2. University Arts & Science College, Subedari, Warangal 9390115327 3. Lalbahadur College, Warangal 9908843686 4. ASM Degree College, (Women), Warangal 9440716045 5. AVV Degree College, Warangal 8790506605 8019274490 WARANGAL RURAL DISTRICT 6. Dr.M.R. Reddy Degree College, Parkal 9948149650 7. S.S. Degree College, Dharmaram 9963591463 MULUGU DISTRICT 8. Aditya Degree College, Mulugu 9. Kakatiya Degree College, Govindaraopet 9010906353 9989223489 MAHABUBABAD DISTRICT 10. Nalanda Degree College, Opp: RTC Bus Stand, 9963156376 Mahabubabad JAYASHANKAR BHUPALAPALLY 11. Vasavi Degree College, Bupalapally 9440232590 9866570569 12. Sangamitra Degree & PG College, Bhupalpally 9542323202 JANGAON DISTRICT 13. S.R.R. (Sri Raja Rajeshwari) Degree College, Suryapet Road, Jangaon 14. R.R.M. Degree College, Jangaon KHAMMAM DISTRICT 15. University PG College, Khammam 7396722446 9966886967 16. Seelam Pulla Reddy Memorial Degree College, Madhira 9848147978 BHADRADRI KOTHAGUDEM DISTRICT 17. Govt. Degree College, Bhadrachalam 9440350225 18. Govt. Degree College, Manuguru 9966521491 19. S.R.R.V.R.K.R. Degree College, Sri Katyayani Educational 9490878878 society, Venkatapuram 20. Gouthami Degree College, Charla 9848586548 21. PSRM Degree College,Bhadrachalam 1 ADILABAD DISTRICT 22. Govt. Degree College, Village & Mand:: Utnoor 9949745845 23. Kakatiya Degree College, Echoda 7013863406 24. Jadhav Radha Bai Degree College, Main Road, 9293177754 Gudihathnoor 9848998410 25. Vaagdevi Arts & Science Degree College, Opp: Girls High 9133561837 School, Adilabad 26. Vidyarthi Degree College, Adilabad 9959868728 27. Tri Devi Degree College, Neredigonda 9441909191 MANCHERIAL DISTRICT 28. MAM & MVN Degree College, Mancherial 9949801637 29. -

Telangana State Information Commission

TELANGANA STATE INFORMATION COMMISSION (Under Right to Information Act, 2005) Samachara Hakku Bhavan, D.No.5-4-399, ‘4’ Storied Commercial Complex, Housing Board Building, Mojam Jahi Market, Hyderabad – 500 001. Phone Nos: 040-24740665 (o); 040-24740592(f) Appeal No.12720/SIC-KSR/2019 Dated: 12-06-2020 Appellant : Sri Devulapalli Shamprasad, Warangal Urban District Respondents : The Public Information Officer (U/RTI Act, 2005) / O/o. The Tahsildar, Mandal Revenue Office, Mangapeta Mandal, Mulugu District The Appellate Authority (U/RTI Act, 2005) / O/o. The Revenue Divisional Officer, Mulugu Division, Mulugu District. O R D E R Sri Devulapalli Shamprasad, Warangal Urban District has filed 2nd appeal dated 24-10-2019 which was received by this Commission on 25-10-2019 for not getting the information sought by him from the PIO / O/o. The Tahsildar, Mandal Revenue Office, Mangapeta Mandal, Mulugu District and 1st Appellate Authority / O/o. The Revenue Divisional Officer, Mulugu Division, Mulugu District. The brief facts of the case as per the appeal and other records received along with it are that the appellant herein filed an application dated 12-06-2019 before the PIO under Sec.6(1) of the RTI Act, 2005, requesting to furnish the information on the following points mentioned in his application: TSIC The Public Information Officer has not furnished the information to the appellant. Since the appellant did not receive the information from the Public Information Officer, he filed 1st appeal dated 16-08-2019 before the 1st Appellate Authority U/s 19(1) of the RTI Act, 2005 requesting him to furnish the information sought by him. -

One Stop Centre Directory (20.05.2020)

ONE STOP CENTRE DIRECTORY (20.05.2020) 1 S.No State/UT District Name Sakhi-One Stop Centre Contact Email Address Date of Address Details Operations 1. Andaman and Nicobars One Stop Centre, Perka, 03193-265121 [email protected] 6th September, Nicobar Islands Headquarters, Car Nicobar, om 2019 (UT) (3) Nicobars- 744301 2. North & One Stop Centre, Old DRDA 03192-273009 sakhiandaman@g 6th September, Middle Office, O/o. The Deputy mail.com 2019 Andaman Commissioner, Near State Library, Mayabunder, North & Middle Andaman-744204 3. South One Stop Centre, JG 6-Type, 0319-2230504 sakhiandaman@g 1st January,2016 Andaman V Quarter, Near Ayush, mail.com (Govt.) Hospital, Junglighat, Port Blair, South Andaman District, Andaman & Nicobar Islands 4. Andhra Pradesh Krishna One Stop Centre, Shaik Raja 9398914772, [email protected] 29th August, (13) Sahib Municipal Maternity 9949397133, m 2015 Hospital, Kothapet, 9440280053, Vijaywada City, Krishna 9398914772 District, Andhra Pradesh 5. Chittoor One Stop Centre, RIMS- 9959776697, [email protected] 15th December, General Hospital, Municipal 8897600654, m 2016 Maternity Ward, Chittoor 9951909222 City, Chittoor District, Andhra Pradesh 2 6. Andhra Pradesh Srikakulam One Stop Centre, RIMS- 9110793708, [email protected] 15th December, General Hospital, Balaga, 7386965008, m 2016 Srikakulam City, Srikakulam 7997879976, District, Andhra Pradesh- 532001 7. Anantapur One Stop Centre, Room 8008053408, [email protected] 15th December, No.12 & 13, Trauma Care, 6281298026, m 2016 Upstairs, Emergency Centre, 9110793708 Govt. General Hospital, Anantapur City, Anantapur District, Andhra Pradesh- 515001 8. Kurnool One Stop Centre, Room 08518-255057, [email protected] 15th December, No.214, Upstairs, 08008471794, m 2016 NtrVidyaSeva, Karyalayam, 09441303332, Govt. -

Finance Minister Launches Online Dashboard For

VVOLOL NNO.O. XXII ISSUEISSUE NNO.O. 334949 PPAGES.AGES. 88+8+8 ` //-- 4 EENGLISHNGLISH DDAILYAILY THE11 TUESDAY, AUGUST, SOUTH 2020 PUBLISHED FROM: HYDERABAD, CHENNAI INDIA & BANGALORE EDITOR INTIMES CHIEF: BUCHI BABU VUPPALA www.thesouthindiatimes.com /facebook/thesouthindiatimes.yahoo.in / thesouthindiatimes.yahoo.in ‘DONE DEAL’: CONGRESS WHO DECRIES ‘VAST GLOBAL BOMMAI, ASHOK HINTS AT UNDERSTANDING GAP’ IN FUNDS NEEDED TO CHIP IN FOR YEDIYURAPPA IN PM’S WITH PILOT CAMP FIGHT CORONAVIRUS FLOOD REVIEW SHORT TAKES PM holds meeting with CMs of six States to review flood situation CBI raids 4 locations New Delhi, Aug 10 (UNI) Prime central and state agencies to have warning systems so that people in for elderly people, pregnant wom- in Ambience Mall case Minister Narendra Modi on Mon- a permanent system for forecasting a particular area can be provided en and people with co-morbidity. day held a meeting, through video of floods and extensive use of inno- with timely warning in case of He further conveyed that States New Delhi, Aug 10 (UNI) The conferencing, with Chief Ministers vative technologies for improving any threatening situation such as should ensure that all develop- Central Bureau of Investigation of six States, namely Assam, Bihar, forecast and warning system. breach of river embankment, in- ment and infrastructure projects (CBI) is carrying out searches at Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra, Kar- Prime Minister said that over undation level, lightning etc. Prime must be built with resilience to four locations in Delhi, Chandi- nataka and Kerala, to review their the past few years, our forecasting Minister also emphasized that in withstand local disasters and to garh, and Panchkula in Haryana, preparedness to deal with south- agencies like India Meteorologi- view of COVID situation, while help in reducing consequential including the premises of the Am- west monsoon and current flood cal Department and Central Water undertaking rescue efforts, States losses.