Nancy Cartwright's Philosophy of Science

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philosophy of Social Science

Philosophy of Social Science Philosophy of Social Science A New Introduction Edited by Nancy Cartwright and Eleonora Montuschi 1 1 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © The several contributors 2014 The moral rights of the authors have been asserted First Edition published in 2014 Impression: 1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Control Number: 2014938929 ISBN 978–0–19–964509–1 (hbk.) ISBN 978–0–19–964510–7 (pbk.) Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. -

Reason and Representation in Scientific Simulation

Reason and Representation in Scientific Simulation Matthew Spencer | PhD Thesis Centre for Cultural Studies, Goldsmiths, University of London Declaration The work presented in this thesis is the candidate's own. - 2 - Abstract This thesis is a study of scientific practice in computational physics. It is based on an 18 month period of ethnographic research at the Imperial College Applied Modelling and Computation Group. Using a theoretical framework drawn from practice theory, science studies, and historical epistemology, I study how simulations are developed and used in science. Emphasising modelling as a process, I explore how software provides a distinctive kind of material for doing science on computers and how images and writings of various kinds are folded into the research process. Through concrete examples the thesis charts how projects are devised and evolve and how they draw together materials and technologies into semi-stable configurations that crystallise around the objects of their concern, what Hans-Jorg Rheinberger dubbed “epistemic things”. The main pivot of the research, however, is the connection of practice-theoretical science studies with the philosophy of Gaston Bachelard, whose concept of “phenomenotechnique” facilitates a rationalist reading of scientific practice. Rather than treating reason as a singular logic or method, or as a faculty of the mind, Bachelard points us towards processes of change within actual scientific research, a dynamic reason immanent to processes of skilled engagement. Combining this study of reason with the more recent attention to things within research from materialist and semiotic traditions, I also revive a new sense for the term “representation”, tracing the multiple relationships and shifting identities and differences that are involved in representing. -

The Unity of Science in Early-Modern Philosophy: Subalternation, Metaphysics and the Geometrical Manner in Scholasticism, Galileo and Descartes

The Unity of Science in Early-Modern Philosophy: Subalternation, Metaphysics and the Geometrical Manner in Scholasticism, Galileo and Descartes by Zvi Biener M.A. in Philosophy, University of Pittsburgh, 2004 B.A. in Physics, Rutgers University, 1995 B.A. in Philosophy, Rutgers University, 1995 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2008 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH FACULTY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Zvi Biener It was defended on April 3, 2008 and approved by Peter Machamer J.E. McGuire Daniel Garber James G. Lennox Paolo Palmieri Dissertation Advisors: Peter Machamer, J.E. McGuire ii Copyright c by Zvi Biener 2008 iii The Unity of Science in Early-Modern Philosophy: Subalternation, Metaphysics and the Geometrical Manner in Scholasticism, Galileo and Descartes Zvi Biener, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2008 The project of constructing a complete system of knowledge—a system capable of integrating all that is and could possibly be known—was common to many early-modern philosophers and was championed with particular alacrity by Ren´eDescartes. The inspiration for this project often came from mathematics in general and from geometry in particular: Just as propositions were ordered in a geometrical demonstration, the argument went, so should propositions be ordered in an overall system of knowledge. Science, it was thought, had to proceed more geometrico. I offer a new interpretation of ‘science more geometrico’ based on an analysis of the explanatory forms used in certain branches of geometry. These branches were optics, as- tronomy, and mechanics; the so-called subalternate, subordinate, or mixed-mathematical sciences. -

Let's Not Talk About Objectivity

Chapter 2 Let’s Not Talk About Objectivity Ian Hacking The first landmark event in twenty-first-century thinking about objectivity was, as is well known, Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison’s Objectivity (2007). It is a magisterial historical study of an epistemological concept, namely “objectivity”. Hence I call it a contribution to what I call (if it wants a name) meta-epistemology, although other prefer the less apt but better sounding historical epistemology. You will find more food for thought, not to mention headaches, in their book, than in any other body of work about objectivity. It will seem that Objectivity rejects the injunction stated in my title, for what is the book about, but objectivity? The authors are talking about objectivity if anyone is! Analytic philosopherslike myself make what others regard as too many distinctions, and I shall illustrate that here. Objectivity is about the concept of objectivity, its past uses, and the practices associated with it. For me, a concept is a word in its sites (Hacking 1984). In this context, that means the sites in which words cognate with “objective” were used over the past three centuries, the practices within which they were deployed, who had authority when using them, the actual modes of inscription, which in this case is closely associated with the use of pictures and other types of images. For me, as for a builder, a site is a rich field of activity to be described from many points of view, almost innumerable perspectives. Objectivity is a triumph of that type of analysis; it is not talking about objectivity but about the concept of objectivity (a distinction we most clearly owe to Gottlob Frege writing about number). -

The Two Cultures” and the Historical Perspective on Science As a Culture Francesca Rochberg, Professor of History, University of California, Riverside

Forum on Public Policy “The Two Cultures” and the Historical Perspective on Science as a Culture Francesca Rochberg, Professor of History, University of California, Riverside Abstract In the Rede lecture of 1959, C.P.Snow speaks in terms of two cultures, one of science, the other of literary intellectuals. Snow’s discussion presupposes that science represents a culture of its own, independent of and superior to the arts and humanities, and unified within itself. At our present distance from this claim, Snow’s point of view can be seen as a product of the philosophical orientation to science as an embodiment of universal truths about nature as well as cold war pressures on the West to improve educational standards in science. As the terms in which science is discussed have changed in the last nearly half-century, so has our response to the terms of Snow’s “Two Cultures”altered with time. The fields of history and sociology of science have shown the degree to which science is both fully enmeshed in society and conditioned by history, making it more difficult to support the idea of a separate “culture” of science immune from the effects of society and history. That the viability of a culture of science as an independent entity is contested in contemporary academic circles furthermore affects the mode in which students of science and the humanities are inculcated. This paper discusses the historical perspective on science as a culture and considers the impact of changing views about the nature, aims, and methods of science on the teaching of science and its history. -

Let's Not Talk About Objectivity

Chapter 2 Let’s Not Talk About Objectivity Ian Hacking The first landmark event in twenty-first-century thinking about objectivity was, as is well known, Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison’s Objectivity (2007). It is a magisterial historical study of an epistemological concept, namely “objectivity”. Hence I call it a contribution to what I call (if it wants a name) meta-epistemology, although other prefer the less apt but better sounding historical epistemology. You will find more food for thought, not to mention headaches, in their book, than in any other body of work about objectivity. It will seem that Objectivity rejects the injunction stated in my title, for what is the book about, but objectivity? The authors are talking about objectivity if anyone is! Analytic philosophers like myself make what others regard as too many distinctions, and I shall illustrate that here. Objectivity is about the concept of objectivity, its past uses, and the practices associated with it. For me, a concept is a word in its sites (Hacking 1984). In this context, that means the sites in which words cognate with “objective” were used over the past three centuries, the practices within which they were deployed, who had authority when using them, the actual modes of inscription, which in this case is closely associated with the use of pictures and other types of images. For me, as for a builder, a site is a rich field of activity to be described from many points of view, almost innumerable perspectives. Objectivity is a triumph of that type of analysis; it is not talking about objectivity but about the concept of objectivity (a distinction we most clearly owe to Gottlob Frege writing about number). -

The Scientist As Philosopher

The Scientist as Philosopher 3 Berlin Heidelberg New York Hong Kong London Milan Paris Tokyo Friedel Weinert The Scientist as Philosopher Philosophical Consequences of Great Scientific Discoveries With 52 Figures 13 Dr. Friedel Weinert University of Bradford Department of Social Sciences and Humanities Bradford BD7 1DP Great Britain e-mail: [email protected] CoverfiguresreproducedfromFaraday,M.:ACourseof6LecturesontheVariousForcesofMatter and Their Relation to Each Other. Ed. by W. Crookes (Griffin, London, Glasgow 1860) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data. Weinert, Friedel, 1950– . The scientist as philosopher: philosophical consequences of great scientific discoveries Friedel Weinert. p.cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 3-540-20580-2 (acid-free paper) 1. Discoveries in science. 2. Science–Philosophy. 3. Philosophy and science. I. Title Q180.55.D57W45 2004 501–dc22 2003064922 ISBN 3-540-21374-0 Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg New York This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broad- casting, reproduction on microfilm or in any other way, and storage in data banks. Duplication of this publication or parts thereof is permitted only under the provisions of the German Copyright Law of September 9, 1965, in its current version, and permission for use must always be obtained from Springer-Verlag. Violations are liable for prosecution under the German Copyright Law. Springer-Verlag is a part of Springer Science+Business Media springeronline.com © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2005 Printed in Germany The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, etc. -

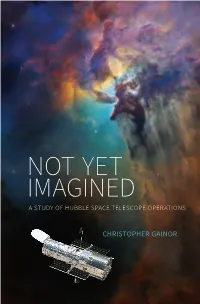

Not Yet Imagined: a Study of Hubble Space Telescope Operations

NOT YET IMAGINED A STUDY OF HUBBLE SPACE TELESCOPE OPERATIONS CHRISTOPHER GAINOR NOT YET IMAGINED NOT YET IMAGINED A STUDY OF HUBBLE SPACE TELESCOPE OPERATIONS CHRISTOPHER GAINOR National Aeronautics and Space Administration Office of Communications NASA History Division Washington, DC 20546 NASA SP-2020-4237 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Gainor, Christopher, author. | United States. NASA History Program Office, publisher. Title: Not Yet Imagined : A study of Hubble Space Telescope Operations / Christopher Gainor. Description: Washington, DC: National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Office of Communications, NASA History Division, [2020] | Series: NASA history series ; sp-2020-4237 | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Summary: “Dr. Christopher Gainor’s Not Yet Imagined documents the history of NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope (HST) from launch in 1990 through 2020. This is considered a follow-on book to Robert W. Smith’s The Space Telescope: A Study of NASA, Science, Technology, and Politics, which recorded the development history of HST. Dr. Gainor’s book will be suitable for a general audience, while also being scholarly. Highly visible interactions among the general public, astronomers, engineers, govern- ment officials, and members of Congress about HST’s servicing missions by Space Shuttle crews is a central theme of this history book. Beyond the glare of public attention, the evolution of HST becoming a model of supranational cooperation amongst scientists is a second central theme. Third, the decision-making behind the changes in Hubble’s instrument packages on servicing missions is chronicled, along with HST’s contributions to our knowledge about our solar system, our galaxy, and our universe. -

David J. Stump Publications: Books: Science and Hypothesis: the Complete Text by Henri Poincaré, a New Translation by Mélanie

David J. Stump Publications: Books: Science and Hypothesis: The Complete Text by Henri Poincaré, a new translation by Mélanie Frappier, Andrea Smith, and David J. Stump; introduction by David J. Stump. New York and London: Bloomsbury, in press. Conceptual Change and the Philosophy of Science: Alternative Interpretations of the A Priori New York and London: Routledge, 2015. The Disunity of Science: Boundaries, Contests, and Power . Peter Galison and David J. Stump, eds. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1996. David J. Stump Publications: Peer Reviewed Articles “Arthur Pap’s Theory of the Functional A Priori” HOPOS (2011) 1(2): 273-290. “A Reconsideration of Newton’s Laws” in What Place for the A Priori? M. Veber & M. Shaffer, eds. Chicago: Open Court, 2011, pp. 177-192. “Pragmatism, Activism, and the Icy Slopes of Logic in George Reisch's Portrait of the Philosophy of Science as a Young Field” Science and Education (2009) 18 (2): 169-175. “Pierre Duhem’s Virtue Epistemology” Studies in History and Philosophy of Science (2007) 18 (1): 149-159. “The Independence of the Parallel Postulate and Development of Rigorous Consistency Proofs” History and Philosophy of Logic (2007) 28 (1): 19-30. "Defending Conventions as Functionally A Priori Knowledge" Philosophy of Science (2003) 20 : 1149-1160. "From the Values of Scientific Philosophy to Value Neutral Philosophy of Science" in History of Philosophy of Science: New Trends and Perspectives , M. Heidelberger & F. Stadler, eds. Dordrecht: Kluwer, 2001, pp. 147-158. "Socially Constructed Technology" (part of a symposium on Andrew Feenberg's Questioning Technology ) Inquiry (2000) 43 : 217-244. "Reconstructing the Unity of Mathematics circa 1900" Perspectives on Science (1997) 5 (3): 383-417. -

Establishing Commensurability: Intercalation, Global Meaning and the Unity of Science

Establishing Commensurability: Intercalation, Global Meaning and the Unity of Science Alfred Nordmann University of South Carolina In the face of disuniªcation and incommensurability, how can the scientiªc community maintain itself and (re-)establish commensurability? According to Peter Galison’s investigations of twentieth-century microphysics, commen- surability is achieved through local coordination even in the absence of global meaning: The “strength and coherence” of science is due to diverse, yet coordi- nated action in trading zones between theorists and experimenters, experiment- ers and instrument builders, etc. Galison’s claim is confronted with Georg Christoph Lichtenberg’s establishment of commensurability between unitarians and dualists in the eighteenth century dispute about electrical ºuids. The contrast of cases suggests an alternative account: Commensurability may be established through the global coordination of local meaning. And where Galison reiªes the disuniªcation of science, this account suggests a dynamic interplay between de facto disuniªcation and an intended unity. This interplay is manifested in the pervasive and ongoing practical concern for the conditions of successful communication in a science that is constantly in-the-making. I In recent years, much of History, Philosophy, even Sociology of Science consisted in attempts to balance two competing historical intuitions: • Incommensurability arises as a matter of course from the under- determination of theories by the evidence, i.e., whenever even agreement on the facts allows for disagreements concerning the adoption or abandonment of a theory or research programme. To the extent that each research programme provides evaluative standards which inform judgements concerning its advance- ment, no research programme provides an internal standard for its abandonment or the surrender of those standards themselves. -

Ten Problems in History and Philosophy of Science

F O C U S Ten Problems in History and Philosophy of Science By Peter Galison* ABSTRACT In surveying the field of history and philosophy of science (HPS), it may be more useful just now to pose some key questions than it would be to lay out the sundry competing attempts to unify H and P. The ten problems this essay presents are grounded in a range of work of enormous interest—historical and philosophical work that has made use of productive categories of analysis: context, historicism, purity, and microhistory, to name but a few. What kind of account are we after—historically and philosophically—when we attempt to address science not as a vacuous generality but in its specific, local formation? N 8 AUGUST 1900, David Hilbert took the podium at the Sorbonne to address the O International Congress of Mathematicians. Rather than a presentation of the usual sort—summing up the speaker’s own work or conducting a high-altitude overview of the field—he presented ten problems from across the discipline’s map. While it would be foolish to belabor parallels between the history and philosophy of science (HPS) and mathematics, or between 2008 and 1900, or (worst of all) between this author and that one, perhaps this is a propitious moment to ask rather than tell. That odd conjunction, “HPS,” covers a multitude of sins, only some of which offer genuine temptation. True, some history of science in the 1930s through the 1950s aimed to use short historical accounts to bolster broad ambitions of a unification of scientific knowledge based on observation statements. -

"Experiment in Physics." Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

pdf version of the entry on Experiment in Physics http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2008/entries/physics-experiment/ Experiment in Physics from the Winter 2008 Edition of the First published Mon Oct 5, 1998; substantive revision Fri Jul 6, 2007 Stanford Encyclopedia Physics, and natural science in general, is a reasonable enterprise based on valid experimental evidence, criticism, and rational discussion. It provides of Philosophy us with knowledge of the physical world, and it is experiment that provides the evidence that grounds this knowledge. Experiment plays many roles in science. One of its important roles is to test theories and to provide the basis for scientific knowledge.[1] It can also call for a new theory, either by showing that an accepted theory is incorrect, or by Edward N. Zalta Uri Nodelman Colin Allen John Perry exhibiting a new phenomenon that is in need of explanation. Experiment Principal Editor Senior Editor Associate Editor Faculty Sponsor can provide hints toward the structure or mathematical form of a theory Editorial Board and it can provide evidence for the existence of the entities involved in http://plato.stanford.edu/board.html our theories. Finally, it may also have a life of its own, independent of Library of Congress Catalog Data theory. Scientists may investigate a phenomenon just because it looks ISSN: 1095-5054 interesting. Such experiments may provide evidence for a future theory to explain. [Examples of these different roles will be presented below.] As Notice: This PDF version was distributed by request to mem- we shall see below, a single experiment may play several of these roles at bers of the Friends of the SEP Society and by courtesy to SEP once.