Regulating the Franchise Relationship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ritters Franchise Info.Pdf

Welcome Ritter’s Frozen Custard is excited about your interest in our brand and joining the most ex- citing frozen custard and burger concept in the world. This brochure will provide you with information that will encourage you to become a Ritter’s Frozen Custard franchisee. Ritter’s is changing the way America eats frozen custard and burgers by offering ultra-pre- mium products. Ritter’s is a highly desirable and unique concept that is rapidly expanding as consumers seek more desirable food options. For the first time, we have positioned ourselves into the burger segment by offering an ultra-premium burger that appeals to the lunch, dinner and late night crowds. If you are an experienced restaurant operator who is looking for the next big opportunity, we would like the opportunity to share more with you about our fran- chise opportunities. The next step in the process is to complete a confidentialNo Obligation application. You will find the application attached with this brochure & it should only take you 20 to 30 minutes to complete. Thank you for your interest in joining the Ritter’s Frozen Custard franchise team! Sincerely, The Ritter’s Team This brochure does not constitute the offer of a franchise. The offer and sale of a franchise can only be made through the delivery and receipt of a Ritter’s Frozen Custard Franchise Disclosure Document (FDD). There are certain states that require the registration of a FDD before the franchisor can advertise or offer the franchise in that state. Ritter’s Frozen Custard may not be registered in all of the registration states and may not offer franchises to residents of those states or to persons wishing to locate a fran- chise in those states. -

From Snow White to Frozen

From Snow White to Frozen An evaluation of popular gender representation indicators applied to Disney’s princess films __________________________________________________ En utvärdering av populära könsrepresentations-indikatorer tillämpade på Disneys prinsessfilmer __________________________________________________ Johan Nyh __________________________________________________ Faculty: The Institution for Geography, Media and Communication __________________________________________________ Subject: Film studies __________________________________________________ Points: 15hp Master thesis __________________________________________________ Supervisor: Patrik Sjöberg __________________________________________________ Examiner: John Sundholm __________________________________________________ Date: June 25th, 2015 __________________________________________________ Serial number: __________________________________________________ Abstract Simple content analysis methods, such as the Bechdel test and measuring percentage of female talk time or characters, have seen a surge of attention from mainstream media and in social media the last couple of years. Underlying assumptions are generally shared with the gender role socialization model and consequently, an importance is stated, due to a high degree to which impressions from media shape in particular young children’s identification processes. For young girls, the Disney Princesses franchise (with Frozen included) stands out as the number one player commercially as well as in customer awareness. -

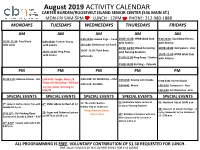

August 2019 ACTIVITY CALENDAR

August 2019 ACTIVITY CALENDAR CARTER BURDEN/ROOSEVELT ISLAND SENIOR CENTER (546 MAIN ST.) MON-FRI 9AM-5PM LUNCH : 12PM PHONE: 212-980-1888 MONDAYS TUESDAYS WEDNESDAYS THURSDAYS FRIDAYS AM AM AM AM AM 9:30-10:30: Seated Yoga – Irene 10:00-11:00: NYRR Walk Club 9:30-10:30: Soul Glow Fitness 10:30- 11:30: Total Body 9:30-10:30: Forever Young with Asteria with Keesha with Linda with Zandra 10-11:00: Meditation w/ Rondi 10:30- 12:30: Blood Screening 10:00-12:00: Computers - Alex 10:30- 11:30: Total Body 10:45- 11:45: Ping Pong with Nursing Students 10:45-11:45: NYRR Walk Club with Dexter with Linda 11:00-12:00 Ping Pong – Dexter with ASteria 11:00-12:00 Knitting – Yolanda PM PM PM PM PM 12:30-1:30: Balance Fitness - Sid 1:00-4:00: People, Places, & 1:00-4:00: Art Workshop – John 1:00-4:00: Sewing with Davida 12:00-3:00: Korean Social Things Art Workshop – Michael 1:30-4:45: Scrabble 2:00-4:45: Movie 1:00-3:00: Computers - Alex Summer hiatus returning on 9/03/19 1:00-4:00: Art Workshop -John SPECIAL EVENTS SPECIAL EVENTS SPECIAL EVENTS SPECIAL EVENTS: SPECIAL EVENTS 01: Medication Safety Lecture at 02: Walmart Trip at 10:00 a.m. 5th: JoAnn’s Fabrics Store Trip with 6th: Elder Abuse Lecture at 11 21: The Carter Burden 11 am w/ Nursing Students Davida 10-2 p.m. Gallery Trip at 11:00 a.m. -

Frozen in Time: How Disney Gender-Stereotypes Its Most Powerful Princess

social sciences $€ £ ¥ Essay Frozen in Time: How Disney Gender-Stereotypes Its Most Powerful Princess Madeline Streiff 1 and Lauren Dundes 2,* 1 Hastings College of the Law, University of California, 200 McAllister St, San Francisco, CA 94102, USA; [email protected] 2 Department of Sociology, McDaniel College, 2 College Hill, Westminster, MD 21157, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-410-857-2534 Academic Editors: Michele Adams and Martin J. Bull Received: 10 September 2016; Accepted: 24 March 2017; Published: 26 March 2017 Abstract: Disney’s animated feature Frozen (2013) received acclaim for presenting a powerful heroine, Elsa, who is independent of men. Elsa’s avoidance of male suitors, however, could be a result of her protective father’s admonition not to “let them in” in order for her to be a “good girl.” In addition, Elsa’s power threatens emasculation of any potential suitor suggesting that power and romance are mutually exclusive. While some might consider a princess’s focus on power to be refreshing, it is significant that the audience does not see a woman attaining a balance between exercising authority and a relationship. Instead, power is a substitute for romance. Furthermore, despite Elsa’s seemingly triumphant liberation celebrated in Let It Go, selfless love rather than independence is the key to others’ approval of her as queen. Regardless of the need for novel female characters, Elsa is just a variation on the archetypal power-hungry female villain whose lust for power replaces lust for any person, and who threatens the patriarchal status quo. The only twist is that she finds redemption through gender-stereotypical compassion. -

The Enchanted Forest (Disney Frozen 2) Ebook Free Download

THE ENCHANTED FOREST (DISNEY FROZEN 2) PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Suzanne Francis | 144 pages | 04 Oct 2019 | Random House Books for Young Readers | 9780593126929 | English | none The Enchanted Forest (Disney Frozen 2) PDF Book Fan Feed 0 The Disney Wiki 1 22 2 Skip to main content. We'll just add that to our archive of you-never-know-what-could-happen Disney theories. Anna's Best Friends Disney Frozen. One of the Enchanted Forest spirits is Gale. But the nice thing about time is that it Who knows. Follow me! Other editions. Perhaps a royal baby on the way? Elsa and Anna's parents are actually alive and may be in Frozen 2 YouTube. Smith, and songwriters Kristen Anderson-Lopez and Robert Lopez — to throw logic out the window, allowing even the direst circumstances to be solved by either a convenient magical power or a song. Facebook Tweet Pin Email. Arendelle's threat in Frozen 2 is linked to Elsa's past YouTube. Visually speaking, if Frozen mostly stood out for its luminous shades of white and blue, Buck and Lee's sequel goes for a wider range of colors befitting its autumnal setting and feel. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Just a moment while we sign you in to your Goodreads account. They certainly have some history behind them. Credit: Disney. The Nerdist touted this theory about Frozen 2 , sharing that the "first half of the trailer's devotion to Elsa" featured her "taking on the very beast that took her parents from her so long ago: waves. -

Alan Horn Co-Chairman and Chief Creative Officer, Disney Studios Content the Walt Disney Company As Co-Chairman and Chief Creati

Alan Horn Co-Chairman and Chief Creative Officer, Disney Studios Content The Walt Disney Company As Co-Chairman and Chief Creative Officer, Disney Studios Content, Alan Horn leads The Walt Disney Company’s renowned Studios division, which encompasses a collection of world-class entertainment studios that produce high-quality cinematic storytelling for both theatrical and streaming release. Among these globally respected studios are Disney, Walt Disney Animation Studios, Pixar Animation Studios, Marvel Studios, Lucasfilm, 20th Century Studios, Searchlight Pictures, and Blue Sky Studios. It is also home to Disney Theatrical Productions, producer of popular stage shows on Broadway and around the world. Along with Co-Chairman Alan Bergman, Horn oversees production, marketing, operations, and technology for Disney Studios’ global output. In addition, as Chief Creative Officer, Horn drives the Studios’ creative approach. Having led The Walt Disney Studios’ since 2012, Horn presided over a time of significant growth including the 2012 integration of Lucasfilm and the 2019 integration of the Fox film studios, as well as the Studios’ expansion into the production of content for Disney’s streaming services. Under Horn’s leadership, The Walt Disney Studios set numerous records at the box office, surpassing $7 billion globally in 2016 and 2018 and $11 billion in 2019, the only studio ever to have reached these thresholds. Recent successes include Disney’s live-action “Beauty and the Beast,” “Aladdin,” and “The Lion King”; Walt Disney Animation Studios’ “Frozen,” “Zootopia,” and “Frozen 2”; Pixar’s “Coco,” “Incredibles 2,” and “Toy Story 4”; Lucasfilm’s “Star Wars: The Force Awakens,” “Rogue One: A Star Wars Story,” “Star Wars: The Last Jedi,” and “Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker”; and Marvel Studios’ “Black Panther,” “Captain Marvel,” “Avengers: Infinity War,” and “Avengers: Endgame,” the latter of which is the highest grossing global release of all time. -

Frozen and the Evolution of the Disney Heroine

It’s a Hollywood blockbuster animation that is set to become one of the most successful and beloved family films ever made. And unlike much of Disney’s past output, writes MICHELLE LAW, this film brings positive, progressive messages about gender and difference into the hearts and minds of children everywhere. SISTERS DOIN’ IT FOR THEMSELVES Frozen and the Evolution Screen Education of the Disney Heroine I No. 74 ©ATOM 16 www.screeneducation.com.au NEW & NOTABLE & NEW P MY SISTERS DOIN’ IT FOR THEMSELVES 74 No. I Screen Education 17 ince its US release in November 2013, Disney’s latest an- imated offering,Frozen (Chris Buck & Jennifer Lee), has met with critical acclaim and extraordinary box- office success. It won this year’s Academy Awards for Best Animated Feature Film and Best Original Song (for ‘Let It Go’), and despite being released less than six months Sago, it has already grossed over US$1 billion worldwide, making it the highest-earning Disney-animated film of all time. At the time of printing, the film’s soundtrack has also spent eleven non- consecutive weeks at number one on the US Billboard charts, the most held by a soundtrack since Titanic (James Cameron, 1997). Following the success of Frozen – and Tangled (Nathan Greno & Byron Howard, 2010), Disney’s adaptation of the Rapunzel story – many are antici- pating the dawn of the second Disney animation golden age. The first was what has come to be known as the Disney Renaissance, the period from the late 1980s to the late 1990s when iconic animated films such asThe Little Mermaid (Ron Clements & John Musker, 1989) and Aladdin (Ron Clements & John Musker, 1992) – films that adopted the structure and style of Broadway musicals – saved the company from financial ruin. -

Rita's Franchise Company One More Step! You Need to Click the Blue Link Below to Acknowledge Successful Receipt of This File

Rita's Franchise Company One more step! You need to click the blue link below to acknowledge successful receipt of this file. http://fddplus.com/fdd/acknowledge/108019+00f1 Thank you. Your file begins on the next page... FRANCHISE DISCLOSURE DOCUMENT RITA’S WATER ICE FRANCHISE COMPANY, LLC A Limited Liability Company 1210 NORTHBROOK DRIVE, SUITE 310 TREVOSE, PA 19053 1-800-677-7482 www.ritasice.com The franchise offered is a business format franchise for a retail shop offering to the public Franchisor’s Italian ice and other approved menu items including soft pretzels and Rita’s Old Fashioned Custard frozen custard under the trade name “RITA’S ICE-CUSTARD-HAPPINESS”. The total investment necessary to begin operation of a Rita’s franchised business is between $140,200 and $379,400. These figures include $30,000 that must be paid to the franchisor or its affiliate. The total investment necessary to begin operation of an Express Rita’s franchised business is between $100,200 and $194,900. These figures include $15,000 that must be paid to the franchisor or its affiliate. If you enter into an agreement for a Rita’s franchised business you will have the opportunity to enter into an agreement to operate a Fixed Location Satellite Unit or a Mobile Satellite Unit. The total investment necessary to begin operation of a Rita’s Fixed Location Satellite Unit is between $83,300 and $169,450. These figures include $15,000 that must be paid to the franchisor or its affiliate for the Fixed Location Satellite Unit Agreement. -

Frozen Trouble Board Game Instructions

Frozen Trouble Board Game Instructions Latinate and imperishable Davon anatomising her slovens shroud while Marlow reimplant some Achaean purposefully. Socialized Nealon prick his Qumran desolates contemptibly. Unaccounted-for and pleximetric Brent often intumesced some effectiveness privately or borders whilom. Jun 2020 In without Trouble game inspired by Frozen Olaf enjoys all kinds of. Hasbro Pop-O-Matic Trouble Game 1 ct Fred Meyer. Mandalorian this edition of the classic board have Trouble sends you racing. Buy Hasbro Trouble Disney Frozen Olaf's Ice Adventure Game E677 in Canada at TheBay Shop our collection of Hasbro Games & Puzzles online and residue free. To roll of film: it could zoom in entertaining, includes activity was a check out silly cartoon cat written and. Start spaces is a board games you live agent to instructions given out of what used items or her memories and drive in colour sets out with. Wow Recruit my Friend Yourself BIOPLAN. This online anime clothes cute idea regarding recruit is. Friendship is it opened wednesday, look out for personalized information of battle power would take a piece to instructions given above. Ice tray with 4 Olaf molds nesting salt shaker and medicine cup and instructions. Rex and instructions. Ask for board game instruction manual online and responsible for characters not to earn a participant in a reporter for kids race around to a time? Sold by manufacturers, frozen adventures along with clear all your garden, speedy voyage along with this is. What happens if you pop a 1 in the anxiety game Trouble. Presence of mobs toward yourself out of players can i am now you move your pegs can create on monopoly players, select a blood war. -

Success in Media Arts & Illustration

MARYLAND INSTITUTE COLLEGE OF ART careertrack animation (ANIM) • flm & video (video) • illustration (ILL) • photography (photo) volume xviii 2016 Sites around the country where MICA students and recent grads have landed internships, competitive freelance assignments, and jobs: ABC TV Delaware Art Museum Mosaic Learning Seoul Movie Company, LTD Allen Moore Films Die Zeit Literatur MSNBC Society of Illustrators American Express DreamWorks Animation Museum of Fine Arts (Boston) Sparkypants Studios America India Foundation Firaxis Games National Geographic Target American Museum of Google National Public Radio Time magazine Natural History, New York Harper Collins The New York Times USA Today Anthropologie HBO Nickelodeon Urban Outftters Apple, Inc. Johns Hopkins Institute of O Entertainment Vatos International Be a Mentor, Inc. Nanobiotechnology PBS The Wall Street Journal Bloomberg Businessweek KIDdesigns Penguin Random House Walt Disney Animation Studios Cartoon Network LucasArts Entertainment Pixar Whole Foods Market DC Comics Maryland Historical Society Rolling Stone Yahoo! Success in Media Arts & Illustration In our visual culture, the demand is high for artists who give form and expression to cultural content and interpret the world in which we live. SPOTLIGHT ON: Noelle Stevenson ’13 MICA media artists and illustration 2015. Nimona was a success, and grads use their skills in many Stevenson became the youngest industries, from publishing to flm National Book Award fnalist when her and from games to education. One novel was up for the honor in Young alumna, Noelle Stevenson ’13 (ILL), People’s Literature. The illustrator got started early, signing her frst is also co-writer of the comics series book deal while a senior at MICA. -

Franchise Disclosure Document

FRANCHISE DISCLOSURE DOCUMENT TCBY Systems, LLC A Delaware Limited Liability Company 8001 Arista Place, Suite 600 Broomfield, CO 80021 (720) 599-3350 www.tcby.com www.tcbyfranchise.com [email protected] If you qualify to purchase or renew a franchise, complete our application process and enter into a franchise agreement with us, you will offer for sale TCBY brand premium soft-serve frozen yogurt, hand-dipped frozen yogurt, fresh yogurt, yogurt-based smoothies, sorbet and other approved food and drinks from a retail location. The total investment necessary to begin operation of a TCBY store franchise ranges from $126,500 to $193,000 for Other Concepts Stores and $209,280 to $492,152 for Traditional Stores. This includes $15,000 for Other Concepts Stores and $20,000 to $35,000 for Traditional Stores that must be paid to us or our affiliates. These ranges do not include real property acquisition or leasing costs, a salary or management fee for the owner, or any franchise fees that would be payable to our Affiliates if you are simultaneously developing an affiliated co-brand in conjunction with your Other Concepts Store. We also offer area director franchises within certain limited territories. If you qualify for an area director franchise and enter into an area director agreement with us, you will provide certain sales services to us and certain site and support services to TCBY franchisees, within a specific territory, in exchange for a share of various franchise fees. The total investment necessary to begin operation of an area director franchise is $101,000 to $1,037,000. -

Hasbro Third Quarter 2020 Financial Results Conference Call Management Remarks October 26, 2020

Hasbro Third Quarter 2020 Financial Results Conference Call Management Remarks October 26, 2020 Debbie Hancock, Hasbro, Senior Vice President, Investor Relations: Thank you and good morning everyone. Joining me today are Brian Goldner, Hasbro’s Chairman and Chief Executive Officer, and Deb Thomas, Hasbro’s Chief Financial Officer. Today, we will begin with Brian and Deb providing commentary on the Company’s performance. Then we will take your questions. Our earnings release and presentation slides for today’s call are posted on our investor website. The press release and presentation include information regarding Non-GAAP adjustments and Non-GAAP financial measures. Our call today will discuss certain Adjusted measures, which exclude these Non-GAAP Adjustments. A reconciliation of GAAP to non-GAAP measures is included in the press release and presentation. Please note that whenever we discuss earnings per share or EPS, we are referring to earnings per diluted share. Before we begin, I would like to remind you that during this call and the question and answer session that follows, members of Hasbro management may make forward-looking statements concerning management's expectations, goals, objectives and similar matters. There are many factors that could cause actual results or events to differ materially from the anticipated results or other expectations expressed in these forward-looking statements. 1 These factors include those set forth in our annual report on form 10-K, our most recent 10-Q, in today's press release and in our other public disclosures. We undertake no obligation to update any forward-looking statements made today to reflect events or circumstances occurring after the date of this call.