In Stereotypes? an Intersectional Analysis of Frozen Anna S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Here I Didn't Dream About All the Potential Stories and Scenarios That Could Unfold in a Possible Sequel

Seek the Truth: Unraveling Frozen II Written by Yumeka June 29, 2020 (1st edition) November 11, 2020 (2nd edition) animeyume.com/yume_dimension twitter.com/Yumeka36 yumeka36.tumblr.com Cover art by Charles Tan behance.net/charlestan twitter.com/charlestan Frozen II screenshots used courtesy of Animation Screencaps animationscreencaps.com/4k-frozen-ii-2019/ Frozen, Frozen II, and all related characters and media are owned by Disney. This is an unofficial, commercial-free digital book that came about from a fan's passion Also, special thanks to Mari Mancusi, author of Dangerous Secrets: the Story of Iduna and Agnarr, for taking the time to answer my questions about the lore and events presented in the book. The help was greatly appreciated! 1 Table of Contents Preface ........................................................................................................... 3 Chapter 1 – Arendelle and the Northuldra .................................................... 5 Chapter 2 – A Voice from the Unknown .................................................... 11 Chapter 3– The Spirits ................................................................................ 19 Chapter 4– Those Shut In and the One Shut Out ....................................... 28 Chapter 5– Magic's Core ............................................................................. 33 Chapter 6– A Bridge Has Two Sides ........................................................... 37 Afterword ................................................................................................... -

Ritters Franchise Info.Pdf

Welcome Ritter’s Frozen Custard is excited about your interest in our brand and joining the most ex- citing frozen custard and burger concept in the world. This brochure will provide you with information that will encourage you to become a Ritter’s Frozen Custard franchisee. Ritter’s is changing the way America eats frozen custard and burgers by offering ultra-pre- mium products. Ritter’s is a highly desirable and unique concept that is rapidly expanding as consumers seek more desirable food options. For the first time, we have positioned ourselves into the burger segment by offering an ultra-premium burger that appeals to the lunch, dinner and late night crowds. If you are an experienced restaurant operator who is looking for the next big opportunity, we would like the opportunity to share more with you about our fran- chise opportunities. The next step in the process is to complete a confidentialNo Obligation application. You will find the application attached with this brochure & it should only take you 20 to 30 minutes to complete. Thank you for your interest in joining the Ritter’s Frozen Custard franchise team! Sincerely, The Ritter’s Team This brochure does not constitute the offer of a franchise. The offer and sale of a franchise can only be made through the delivery and receipt of a Ritter’s Frozen Custard Franchise Disclosure Document (FDD). There are certain states that require the registration of a FDD before the franchisor can advertise or offer the franchise in that state. Ritter’s Frozen Custard may not be registered in all of the registration states and may not offer franchises to residents of those states or to persons wishing to locate a fran- chise in those states. -

From Snow White to Frozen

From Snow White to Frozen An evaluation of popular gender representation indicators applied to Disney’s princess films __________________________________________________ En utvärdering av populära könsrepresentations-indikatorer tillämpade på Disneys prinsessfilmer __________________________________________________ Johan Nyh __________________________________________________ Faculty: The Institution for Geography, Media and Communication __________________________________________________ Subject: Film studies __________________________________________________ Points: 15hp Master thesis __________________________________________________ Supervisor: Patrik Sjöberg __________________________________________________ Examiner: John Sundholm __________________________________________________ Date: June 25th, 2015 __________________________________________________ Serial number: __________________________________________________ Abstract Simple content analysis methods, such as the Bechdel test and measuring percentage of female talk time or characters, have seen a surge of attention from mainstream media and in social media the last couple of years. Underlying assumptions are generally shared with the gender role socialization model and consequently, an importance is stated, due to a high degree to which impressions from media shape in particular young children’s identification processes. For young girls, the Disney Princesses franchise (with Frozen included) stands out as the number one player commercially as well as in customer awareness. -

Cars Tangled Finding Nemo Wreck It Ralph Peter Pan Frozen Toy Story Monsters Inc. Snow White Alice in Wonderland the Little Merm

FRIDAY, APRIL 3RD – DISNEY DAY… AT HOME! Activity 1: • Disney Pictionary: o Put Disney movies and character names onto little pieces of paper and fold them in half o Put all of the pieces of paper into a bowl o Then draw it for their team to guess Can add a charade element to it rather than drawing if that is preferred o If there are enough people playing, you can make teams • Here are some ideas, you can print these off and cut them out or create your own list! Cars Tangled Finding Nemo Wreck It Ralph Peter Pan Frozen Toy Story Monsters Inc. Snow White Alice in Wonderland The Little Mermaid Up Brave Robin Hood Aladdin Cinderella Sleeping Beauty The Emperor’s New Groove The Jungle Book The Lion King Beauty and the Beast The Princess and the Frog 101 Dalmatians Lady and the Tramp A Bug’s Life The Fox and the Hound Mulan Tarzan The Sword and the Stone The Incredibles The Rescuers Bambi Fantasia Dumbo Pinocchio Lilo and Stitch Chicken Little Bolt Pocahontas The Hunchback of Notre Wall-E Hercules Dame Mickey Mouse Minnie Mouse Goofy Donald Duck Sully Captain Hook Ariel Ursula Maleficent FRIDAY, APRIL 3RD – DISNEY DAY… AT HOME! The Genie Simba Belle Buzz Lightyear Woody Mike Wasowski Cruella De Ville Olaf Anna Princess Jasmine Lightning McQueen Elsa Activity 2: • Disney Who Am I: o Have each family member write the name of a Disney character on a sticky note. Don’t let others see what you have written down. o Take your sticky note and put it on another family members back. -

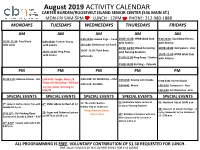

August 2019 ACTIVITY CALENDAR

August 2019 ACTIVITY CALENDAR CARTER BURDEN/ROOSEVELT ISLAND SENIOR CENTER (546 MAIN ST.) MON-FRI 9AM-5PM LUNCH : 12PM PHONE: 212-980-1888 MONDAYS TUESDAYS WEDNESDAYS THURSDAYS FRIDAYS AM AM AM AM AM 9:30-10:30: Seated Yoga – Irene 10:00-11:00: NYRR Walk Club 9:30-10:30: Soul Glow Fitness 10:30- 11:30: Total Body 9:30-10:30: Forever Young with Asteria with Keesha with Linda with Zandra 10-11:00: Meditation w/ Rondi 10:30- 12:30: Blood Screening 10:00-12:00: Computers - Alex 10:30- 11:30: Total Body 10:45- 11:45: Ping Pong with Nursing Students 10:45-11:45: NYRR Walk Club with Dexter with Linda 11:00-12:00 Ping Pong – Dexter with ASteria 11:00-12:00 Knitting – Yolanda PM PM PM PM PM 12:30-1:30: Balance Fitness - Sid 1:00-4:00: People, Places, & 1:00-4:00: Art Workshop – John 1:00-4:00: Sewing with Davida 12:00-3:00: Korean Social Things Art Workshop – Michael 1:30-4:45: Scrabble 2:00-4:45: Movie 1:00-3:00: Computers - Alex Summer hiatus returning on 9/03/19 1:00-4:00: Art Workshop -John SPECIAL EVENTS SPECIAL EVENTS SPECIAL EVENTS SPECIAL EVENTS: SPECIAL EVENTS 01: Medication Safety Lecture at 02: Walmart Trip at 10:00 a.m. 5th: JoAnn’s Fabrics Store Trip with 6th: Elder Abuse Lecture at 11 21: The Carter Burden 11 am w/ Nursing Students Davida 10-2 p.m. Gallery Trip at 11:00 a.m. -

Tangled Study Notes Disney Studios Motion Pictures ©Walt

Tangled Study Notes Pictures Motion Studios Disney ©Walt Directed by: Nathan Greno and Byron Howard Certificate: PG (contains mild violence, threat and brief sight of blood) Running time: 108 mins Release date: 21 January 2011 Synopsis: Disney presents a new twist on one of the most hair-raising tales ever told. When the kingdom’s most wanted – and most charming – bandit Flynn Rider hides in a mysterious tower, the last thing he expects to find is Rapunzel, a spirited teen with an unlikely superpower – 70 feet of magical golden hair! Together, the unlikely duo sets off on a fantastic journey filled with surprising heroes, laughter and suspense. (Disney.go.com/disneypictures/tangled) The activities in these Study Notes address aspects of the curriculum for Literacy, Drama, Maths (24 hour clocks and timetabling, Year 5) and Art for pupils aged 5-11. 1 www.filmeducation.org www.nationalschoolsfilmweek.org ©Film Education July 2011. Film Education is not responsible for the content of external websites. Before seeing the film 1. The long-haired heroine of Tangled, Rapunzel, has grown up grounded. She lives in a tower in the middle of a forest. She dreams of being able to escape from her tower for just one day. If you were able to take her out for one day, what would you show her? Choose carefully, as you only have one day. Timetable your day, showing how you would structure your activities with Rapunzel. 2. The actors behind the animation in Tangled had the task of bringing the character to life using just their voices. -

Bob Iger Kevin Mayer Michael Paull Randy Freer James Pitaro Russell

APRIL 11, 2019 Disney Speakers: Bob Iger Chairman and Chief Executive Officer Kevin Mayer Chairman, Direct-to-Consumer & International Michael Paull President, Disney Streaming Services Randy Freer Chief Executive Officer, Hulu James Pitaro Co-Chairman, Disney Media Networks Group and President, ESPN Russell Wolff Executive Vice President & General Manager, ESPN+ Uday Shankar President, The Walt Disney Company Asia Pacific and Chairman, Star & Disney India Ricky Strauss President, Content & Marketing, Disney+ Jennifer Lee Chief Creative Officer, Walt Disney Animation Studios ©Disney Disney Investor Day 2019 April 11, 2019 Disney Speakers (continued): Pete Docter Chief Creative Officer, Pixar Kevin Feige President, Marvel Studios Kathleen Kennedy President, Lucasfilm Sean Bailey President, Walt Disney Studios Motion Picture Productions Courteney Monroe President, National Geographic Global Television Networks Gary Marsh President & Chief Creative Officer, Disney Channel Agnes Chu Senior Vice President of Content, Disney+ Christine McCarthy Senior Executive Vice President and Chief Financial Officer Lowell Singer Senior Vice President, Investor Relations Page 2 Disney Investor Day 2019 April 11, 2019 PRESENTATION Lowell Singer – Senior Vice President, Investor Relations, The Walt Disney Company Good afternoon. I'm Lowell Singer, Senior Vice President of Investor Relations at THe Walt Disney Company, and it's my pleasure to welcome you to the webcast of our Disney Investor Day 2019. Over the past 1.5 years, you've Had many questions about our direct-to-consumer strategy and services. And our goal today is to answer as many of them as possible. So let me provide some details for the day. Disney's CHairman and CHief Executive Officer, Bob Iger, will start us off. -

Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE May 2016 Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network Laura Osur Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Osur, Laura, "Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network" (2016). Dissertations - ALL. 448. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/448 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract When Netflix launched in April 1998, Internet video was in its infancy. Eighteen years later, Netflix has developed into the first truly global Internet TV network. Many books have been written about the five broadcast networks – NBC, CBS, ABC, Fox, and the CW – and many about the major cable networks – HBO, CNN, MTV, Nickelodeon, just to name a few – and this is the fitting time to undertake a detailed analysis of how Netflix, as the preeminent Internet TV networks, has come to be. This book, then, combines historical, industrial, and textual analysis to investigate, contextualize, and historicize Netflix's development as an Internet TV network. The book is split into four chapters. The first explores the ways in which Netflix's development during its early years a DVD-by-mail company – 1998-2007, a period I am calling "Netflix as Rental Company" – lay the foundations for the company's future iterations and successes. During this period, Netflix adapted DVD distribution to the Internet, revolutionizing the way viewers receive, watch, and choose content, and built a brand reputation on consumer-centric innovation. -

Frozen in Time: How Disney Gender-Stereotypes Its Most Powerful Princess

social sciences $€ £ ¥ Essay Frozen in Time: How Disney Gender-Stereotypes Its Most Powerful Princess Madeline Streiff 1 and Lauren Dundes 2,* 1 Hastings College of the Law, University of California, 200 McAllister St, San Francisco, CA 94102, USA; [email protected] 2 Department of Sociology, McDaniel College, 2 College Hill, Westminster, MD 21157, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-410-857-2534 Academic Editors: Michele Adams and Martin J. Bull Received: 10 September 2016; Accepted: 24 March 2017; Published: 26 March 2017 Abstract: Disney’s animated feature Frozen (2013) received acclaim for presenting a powerful heroine, Elsa, who is independent of men. Elsa’s avoidance of male suitors, however, could be a result of her protective father’s admonition not to “let them in” in order for her to be a “good girl.” In addition, Elsa’s power threatens emasculation of any potential suitor suggesting that power and romance are mutually exclusive. While some might consider a princess’s focus on power to be refreshing, it is significant that the audience does not see a woman attaining a balance between exercising authority and a relationship. Instead, power is a substitute for romance. Furthermore, despite Elsa’s seemingly triumphant liberation celebrated in Let It Go, selfless love rather than independence is the key to others’ approval of her as queen. Regardless of the need for novel female characters, Elsa is just a variation on the archetypal power-hungry female villain whose lust for power replaces lust for any person, and who threatens the patriarchal status quo. The only twist is that she finds redemption through gender-stereotypical compassion. -

Digital Media: Rise of On-Demand Content 2 Contents

Digital Media: Rise of On-demand Content www.deloitte.com/in 2 Contents Foreword 04 Global Trends: Transition to On-Demand Content 05 Digital Media Landscape in India 08 On-demand Ecosystem in India 13 Prevalent On-Demand Content Monetization Models 15 On-Demand Content: Music Streaming 20 On-Demand Content: Video Streaming 28 Conclusion 34 Acknowledgements 35 References 36 3 Foreword Welcome to the Deloitte’s point of view about the rise key industry trends and developments in key sub-sectors. of On-demand Content consumption through digital In some cases, we seek to identify the drivers behind platforms in India. major inflection points and milestones while in others Deloitte’s aim with this point of view is to catalyze our intent is to explain fundamental challenges and discussions around significant developments that may roadblocks that might need due consideration. We also require companies or governments to respond. Deloitte aim to cover the different monetization methods that provides a view on what may happen, what could likely the players are experimenting with in the evolving Indian occur as a consequence, and the likely implications for digital content market in order to come up with the various types of ecosystem players. most optimal operating model. This publication is inspired by the huge opportunity Arguably, the bigger challenge in identification of the Hemant Joshi presented by on-demand content, especially digital future milestones about this evolving industry and audio and video in India. Our objective with this report ecosystem is not about forecasting what technologies is to analyze the key market trends in past, and expected or services will emerge or be enhanced, but in how they developments in the near to long-term future which will be adopted. -

The Effects of Disney Princess Movies on Girls

The Effects of Disney Princess Movies on Girls By Camille Porter-Phillips Eighth grade project research paper Hilltown Cooperative Charter Public School June 2014 1 Introduction Personally, before this project, I thought that the Disney princesses were foolish. People have been watching Disney movies for nearly 100 years and through the course of this project I realized that they are actually really foolish and my beliefs were affirmed. Since the Walt Disney company started in 1923 (Gillies), its movies have become very widespread and pervasive. My question is, have Disney princess movies affected girls? In this essay I will show that watching princess movies affects girls’ independence and body image. I will first give a background of Disney and their princesses, then show how the princess films might affect girls and then describe how to evaluate them. Background The first princess movie the Walt Disney company produced was Snow White, in 1937. It was the first animated feature film to come out of the0 U.S. (Disney). Next came Cinderella, in 1950. Then Sleeping Beauty in 1959. Thirty years later in 1989 The Little Mermaid came out. Then in 1991 Beauty and the Beast. The very next year in 1992 Aladdin came to theaters. Then Pocahontas, in 1995. But this was not the last one, more and more princess movies are produced by Disney every few years. Snow White is about a girl who runs away from an evil queen because the queen wants to kill Snow White. When she meets 12 dwarfs she is happy to cook and take care of them. -

Redefining Gender in Disney Films from the 20Th to 21St Century Shrien Alshabasy SUNY New Paltz Honors Thesis 2018-2019

Alshabasy 1 "A Whole New World": Redefining Gender in Disney Films from the 20th to 21st Century Shrien Alshabasy SUNY New Paltz Honors Thesis 2018-2019 Alshabasy 2 The Disney Dynasty is as familiar to American culture as apple pie. Sitting on land that is twice the size of Manhattan, the Disney Kingdom has expanded over the years to create a whole new world; a world seriously considered by cultural theorists like Baudrillard, as a simulacrum, a symbol so close to reality that it becomes hyperreality. Before water parks and resort hotels, before Disney bought out the land of orange groves and walnut trees in Anaheim, California, the Magic Kingdom began its conquest on American ideology. The Walt Disney Company started in 1923 as “The Disney Brothers Cartoon Studio,” and churned out films that embodied American ideals. Oftentimes, these films were set in 19th century rural America and featured an American hero -- usually Mickey Mouse, who could outwork and challenge any enemy big or small with his bravery. An embodiment of American ideals, Disney films became loved and endeared by audiences during morally depleting times, like the Depression years (“How Disney Came to Define What Constitutes the American Experience”). Audiences latched onto these ideals, seemingly stable, even when external factors were not. In 1938, Disney shifted gears into feature films with his vision of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Although many had their doubts, after three years of work Snow White was released and it quickly became the highest grossing film of all time. Feature films became the money makers for Disney and the start of consumer fascination with Disney culture (“Disney Animation Is Closing the Book on Fairy Tales”).