Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

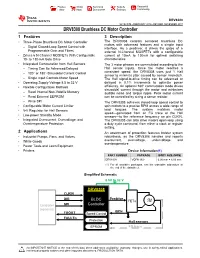

Brushless DC Motor Controller

ON Semiconductor Is Now To learn more about onsemi™, please visit our website at www.onsemi.com onsemi and and other names, marks, and brands are registered and/or common law trademarks of Semiconductor Components Industries, LLC dba “onsemi” or its affiliates and/or subsidiaries in the United States and/or other countries. onsemi owns the rights to a number of patents, trademarks, copyrights, trade secrets, and other intellectual property. A listing of onsemi product/patent coverage may be accessed at www.onsemi.com/site/pdf/Patent-Marking.pdf. onsemi reserves the right to make changes at any time to any products or information herein, without notice. The information herein is provided “as-is” and onsemi makes no warranty, representation or guarantee regarding the accuracy of the information, product features, availability, functionality, or suitability of its products for any particular purpose, nor does onsemi assume any liability arising out of the application or use of any product or circuit, and specifically disclaims any and all liability, including without limitation special, consequential or incidental damages. Buyer is responsible for its products and applications using onsemi products, including compliance with all laws, regulations and safety requirements or standards, regardless of any support or applications information provided by onsemi. “Typical” parameters which may be provided in onsemi data sheets and/ or specifications can and do vary in different applications and actual performance may vary over time. All operating parameters, including “Typicals” must be validated for each customer application by customer’s technical experts. onsemi does not convey any license under any of its intellectual property rights nor the rights of others. -

DRM105, PM Sinusoidal Motor Vector Control with Quadrature

PM Sinusoidal Motor Vector Control with Quadrature Encoder Designer Reference Manual Devices Supported: MCF51AC256 Document Number: DRM105 Rev. 0 09/2008 How to Reach Us: Home Page: www.freescale.com Web Support: http://www.freescale.com/support USA/Europe or Locations Not Listed: Freescale Semiconductor, Inc. Technical Information Center, EL516 2100 East Elliot Road Tempe, Arizona 85284 1-800-521-6274 or +1-480-768-2130 www.freescale.com/support Europe, Middle East, and Africa: Freescale Halbleiter Deutschland GmbH Technical Information Center Information in this document is provided solely to enable system and Schatzbogen 7 software implementers to use Freescale Semiconductor products. There are 81829 Muenchen, Germany no express or implied copyright licenses granted hereunder to design or +44 1296 380 456 (English) fabricate any integrated circuits or integrated circuits based on the +46 8 52200080 (English) information in this document. +49 89 92103 559 (German) +33 1 69 35 48 48 (French) www.freescale.com/support Freescale Semiconductor reserves the right to make changes without further notice to any products herein. Freescale Semiconductor makes no warranty, Japan: representation or guarantee regarding the suitability of its products for any Freescale Semiconductor Japan Ltd. particular purpose, nor does Freescale Semiconductor assume any liability Headquarters arising out of the application or use of any product or circuit, and specifically ARCO Tower 15F disclaims any and all liability, including without limitation consequential or 1-8-1, Shimo-Meguro, Meguro-ku, incidental damages. “Typical” parameters that may be provided in Freescale Tokyo 153-0064 Semiconductor data sheets and/or specifications can and do vary in different Japan applications and actual performance may vary over time. -

Vector Control of an Induction Motor Based on a DSP

Vector Control of an Induction Motor based on a DSP Master of Science Thesis QIAN CHENG LEI YUAN Department of Energy and Environment Division of Electric Power Engineering CHALMERS UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY G¨oteborg, Sweden 2011 Vector Control of an Induction Motor based on a DSP QIAN CHENG LEI YUAN Department of Energy and Environment Division of Electric Power Engineering CHALMERS UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY G¨oteborg, Sweden 2011 Vector Control of an Induction Motor based on a DSP QIAN CHENG LEI YUAN © QIAN CHENG LEI YUAN, 2011. Department of Energy and Environment Division of Electric Power Engineering Chalmers University of Technology SE–412 96 G¨oteborg Sweden Telephone +46 (0)31–772 1000 Chalmers Bibliotek, Reproservice G¨oteborg, Sweden 2011 Vector Control of an Induction Motor based on a DSP QIAN CHENG LEI YUAN Department of Energy and Environment Division of Electric Power Engineering Chalmers University of Technology Abstract In this thesis project, a vector control system for an induction motor is implemented on an evaluation board. By comparing the pros and cons of eight candidates of evaluation boards, the TMS320F28335 DSP Experimenter Kit is selected as the digital controller of the vector control system. Necessary peripheral and interface circuits are built for the signal measurement, the three-phase inverter control and the system protection. These circuits work appropriately except that the conditioning circuit for analog-to-digital con- version contains too much noise. At the stage of the control algorithm design, the designed vector control system is simulated in Matlab/Simulink with both S-function and Simulink blocks. The simulation results meet the design specifications well. -

Electrical: 16422

SECTION 16422 – VARIABLE FREQUENCY DRIVES PART 1 - GENERAL 1.01 SUMMARY A. Section Includes: Types of motor controllers, including: 1. Variable Frequency Drives 1.02 DEFINITIONS A. CPT: Control power transformer. B. DDC: Direct digital control. C. EMI: Electromagnetic interference. D. OCPD: Overcurrent protective device. E. PID: Control action, proportional plus integral plus derivative. F. RFI: Radio-frequency interference. G. VFD: Variable-frequency Drive motor controller. 1.03 SUBMITTALS A. Shop Drawings: For each VFD indicated. 1. Include details of equipment assemblies. Indicate dimensions, weights, loads, and required clearances, method of field assembly, components, and location and size of each field connection. 2. Include diagrams for power, signal, and control wiring. 3. Provide manufacturer recommended spare parts list in with submittal. 4. Installation and Maintenance manuals shall be shipped with the VFD and shall be in electronic format. Include website, detailed installation, start-up, and checkout procedures, adjustment and troubleshooting information, and related closeout documents. Provide OWNER with 3 copies each on separate, clearly labeled jump drives, one jump drive to be housed onsite. 5. Submit evidence that the equipment will be provided with all specified controls, features, options and accessories. 6. Submit certification that the equipment is designed and manufactured in conformance with all applicable codes and standards. 7. Certified copies of test results shall be submitted for tests specified in this section, including but not all inclusive, manufacturer startup. 8. Submit warranty information for equipment. Warranties to start from date of startup. Manufacturer startup certificate may extend warranty, if so provide new warranty update to OWNER. 1.04 CLOSEOUT SUBMITTALS 16422-1 A. -

EV Power Systems (Motors and Controllers)

EV Power Systems (Motors and controllers) The power system of an electric vehicle consists of just two components: the motor that provides the power and the controller that controls the application of this power. In comparison, the power system of gasoline-powered vehicles consists of a number of components, such as the engine, carburetor, oil pump, water pump, cooling system, starter, exhaust system, etc. Motors Electric motors convert electrical energy into mechanical energy. Two types of electric motors are used in electric vehicles to provide power to the wheels: the direct current (DC) motor and the alternating current (AC) motor. DC electric motors have three main components: • A set of coils (field) that creates the magnetic forces which provide torque • A rotor or armature mounted on bearings that turns inside the field • Commutating device that reverses the magnetic forces and makes the armature turn, thereby providing horsepower. As in the DC motor, an AC motor also has a set of coils (field) and a rotor or armature, however, since there is a continuous current reversal, a commutating device is not needed. Both types of electric motors are used in electric vehicles and have advantages and disadvantages, as shown here. While the AC motor is less expensive and lighter weight, the DC motor has a simpler controller, making the DC motor/controller combination less expensive. The main disadvantage of the AC motor is the cost of the electronics package needed to convert (invert) the battery‘s direct current to alternating current for the motor. Past generations of electric vehicles used the DC motor/controller system because they operate off the battery current without complex electronics. -

Piezoelectric Inertia Motors—A Critical Review of History, Concepts, Design, Applications, and Perspectives

Review Piezoelectric Inertia Motors—A Critical Review of History, Concepts, Design, Applications, and Perspectives Matthias Hunstig Grube 14, 33098 Paderborn, Germany; [email protected] Academic Editor: Delbert Tesar Received: 26 November 2016; Accepted: 18 January 2017; Published: 6 February 2017 Abstract: Piezoelectric inertia motors—also known as stick-slip motors or (smooth) impact drives—use the inertia of a body to drive it in small steps by means of an uninterrupted friction contact. In addition to the typical advantages of piezoelectric motors, they are especially suited for miniaturisation due to their simple structure and inherent fine-positioning capability. Originally developed for positioning in microscopy in the 1980s, they have nowadays also found application in mass-produced consumer goods. Recent research results are likely to enable more applications of piezoelectric inertia motors in the future. This contribution gives a critical overview of their historical development, functional principles, and related terminology. The most relevant aspects regarding their design—i.e., friction contact, solid state actuator, and electrical excitation—are discussed, including aspects of control and simulation. The article closes with an outlook on possible future developments and research perspectives. Keywords: inertia motor; stick-slip motor; smooth impact drive; piezeoelectric motor; review 1. Introduction Piezoelectric actuators have long been used in diverse applications, especially because of their short response time and high resolution. The major drawback of these solid state actuators in positioning applications is their small stroke: actuators made of state-of-the-art lead zirconate titanate (PZT) ceramics only reach strains up to 2 . A typical piezoelectric actuator with 10 mm length thus reaches a maximum stroke of only 20 µm.h Bending actuator designs [1] and other mechanisms [2] can increase the stroke at the expense of stiffness and actuation force ([3]; [4] (pp. -

Brushless DC Electric Motor

Please read: A personal appeal from Wikipedia author Dr. Sengai Podhuvan We now accept ₹ (INR) Brushless DC electric motor From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search A microprocessor-controlled BLDC motor powering a micro remote-controlled airplane. This external rotor motor weighs 5 grams, consumes approximately 11 watts (15 millihorsepower) and produces thrust of more than twice the weight of the plane. Contents [hide] 1 Brushless versus Brushed motor 2 Controller implementations 3 Variations in construction 4 AC and DC power supplies 5 KM rating 6 Kv rating 7 Applications o 7.1 Transport o 7.2 Heating and ventilation o 7.3 Industrial Engineering . 7.3.1 Motion Control Systems . 7.3.2 Positioning and Actuation Systems o 7.4 Stepper motor o 7.5 Model engineering 8 See also 9 References 10 External links Brushless DC motors (BLDC motors, BL motors) also known as electronically commutated motors (ECMs, EC motors) are electric motors powered by direct-current (DC) electricity and having electronic commutation systems, rather than mechanical commutators and brushes. The current-to-torque and frequency-to-speed relationships of BLDC motors are linear. BLDC motors may be described as stepper motors, with fixed permanent magnets and possibly more poles on the rotor than the stator, or reluctance motors. The latter may be without permanent magnets, just poles that are induced on the rotor then pulled into alignment by timed stator windings. However, the term stepper motor tends to be used for motors that are designed specifically to be operated in a mode where they are frequently stopped with the rotor in a defined angular position; this page describes more general BLDC motor principles, though there is overlap. -

Alternator Charging System for Electric Motorcycles

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395 -0056 Volume: 04 Issue: 04 | Apr -2017 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072 Alternator Charging System for Electric Motorcycles R. D. Belekar#,Shweta Subramanian1, Pratik Vinay Panvalkar2, Medha Desai3 , Ronit Patole4 # Assistant Professor, Mechanical Department, Rajendra Mane College of Engineering and Technology, Univ. of Mumbai, India 1234 Student, Mechanical Department, Rajendra Mane College of Engineering and Technology, Univ. of Mumbai, India ---------------------------------------------------------------------***-------------------------------------------------------------------- ABSTRACT- The following project deals with modelling the vehicle and are used to propel the motorcycle as an and testing of a battery electric motorcycle with a self- alternative to using an internal combustion engine. charging system for obtaining better utilization of the energy. An attempt to fabricate a regenerative system The efficiency of an electric vehicle is far greater than for a BEV which utilises the rotational energy of wheels all other forms of propulsion currently in use. to restore the energy to the batteries, thereby Whenever there is employment of electricity, the introducing a system which makes the most of the power vehicles using it tend to produces zero emission at the produced by the electric motor. The chassis of a tailpipe. Also, EVs offer great performance and are far commercially available motorcycle is modified as per the from being slow. An electric vehicle operates requirements of the battery sizes and the self-charging differently from a vehicle with an IC engine. An all- system. The components like alternator, motor and DC- electric vehicle is powered by electricity with a large DC converter was arranged in a manner to transfer the rechargeable battery, an electric motor, a controller rotational energy being experienced by the chain that sends electricity to the motor from the driver’s sprockets through the chain to the alternator. -

Tr-Avt-047-$$All

NORTH ATLANTIC TREATY RESEARCH AND TECHNOLOGY ORGANISATION ORGANISATION AC/323(AVT-047)TP/61 www.rta.nato.int RTO TECHNICAL REPORT TR-AVT-047 All Electric Combat Vehicles (AECV) for Future Applications (Les véhicules de combat tout électrique (AECV) pour de futures applications) Report of the RTO Applied Vehicle Technology Panel (AVT) Task Group AVT-047 (WG-015). Published July 2004 Distribution and Availability on Back Cover NORTH ATLANTIC TREATY RESEARCH AND TECHNOLOGY ORGANISATION ORGANISATION AC/323(AVT-047)TP/61 www.rta.nato.int RTO TECHNICAL REPORT TR-AVT-047 All Electric Combat Vehicles (AECV) for Future Applications (Les véhicules de combat tout électrique (AECV) pour de futures applications) Report of the RTO Applied Vehicle Technology Panel (AVT) Task Group AVT-047 (WG-015). The Research and Technology Organisation (RTO) of NATO RTO is the single focus in NATO for Defence Research and Technology activities. Its mission is to conduct and promote co-operative research and information exchange. The objective is to support the development and effective use of national defence research and technology and to meet the military needs of the Alliance, to maintain a technological lead, and to provide advice to NATO and national decision makers. The RTO performs its mission with the support of an extensive network of national experts. It also ensures effective co-ordination with other NATO bodies involved in R&T activities. RTO reports both to the Military Committee of NATO and to the Conference of National Armament Directors. It comprises a Research and Technology Board (RTB) as the highest level of national representation and the Research and Technology Agency (RTA), a dedicated staff with its headquarters in Neuilly, near Paris, France. -

Current-Limiting Soft Starting Method for a High-Voltage and High-Power Motor

energies Article Current-Limiting Soft Starting Method for a High-Voltage and High-Power Motor Yifei Wang 1,2, Kaiyang Yin 1,*, Youxin Yuan 1 and Jing Chen 1 1 School of Automation, Wuhan University of Technology, Wuhan 430070, China 2 Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI 53706, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 17 July 2019; Accepted: 8 August 2019; Published: 9 August 2019 Abstract: Focusing on the starting problems of a high-voltage and high-power motor, such as large starting current, low power factor, waste of resources, and lack of harmonic control, this paper proposes a current-limiting soft starting method for a high-voltage and high-power motor. The method integrates functions like autotransformer voltage reduction–current limiting starting, magnetron voltage regulation–current limiting starting, and reactive power compensation during starting, and then the power filtering subsystem is turned on to filter out harmonics in power system as the starting process terminates. According to the current-limiting starting characteristic curve, the topological structure of the integrated device is established and then the functional logic switching strategy is put forward. Afterwards, the mechanisms of current-limiting starting, reactive compensation and dynamic harmonic filtering are analyzed, and the simulation and experimental evaluation are completed. In particular, the direct starting and the current-limiting are performed by developing a simulation system. In addition, a 10 kV/19,000 kW fan-loaded motor of a steel plant is chosen as the subject to verify the performance of the current-limiting soft starting method. -

AC Induction Motor Vector Control, Driven by Etpu on MPC5500 Covers MPC5500 and All Etpu-Equipped Devices

Freescale Semiconductor AN3001 Application Note Rev. 0, 06/2006 AC Induction Motor Vector Control, Driven by eTPU on MPC5500 Covers MPC5500 and all eTPU-Equipped Devices by: Milan Brejl & Michal Princ System Application Engineers Roznov Czech System Center This application note describes the design of a 3-phase Table of Contents AC induction motor (ACIM) speed and torque vector 1 PowerPC MPC5554 and eTPU Advantages and Features ..............................................................2 control drive based on Freescale’s PowerPC MPC5500 2 Target Motor Theory............................................4 microprocessor. The application design takes advantage 3 System Concept ..................................................7 of the enhanced time processing unit (eTPU) module, 4 Software Design ................................................17 which is used as a motor control co-processor. The eTPU 5 Implementation Notes .......................................44 6 Microprocessor Usage ......................................45 handles the motor control processing, eliminating the 7 Summary and Conclusions ...............................46 microprocessor overhead for other duties. 8 References ........................................................47 9 Revision History ................................................47 AC induction motors, which contain a cage, are very popular in variable speed drives. They are simple, rugged, inexpensive, and available at all power ratings. Progress in the field of power electronics and microelectronics enables the application of induction motors for high-performance drives, where traditionally only DC motors were applied. Thanks to sophisticated control methods, AC induction drives offer the same control capabilities as high performance four-quadrant DC drives. The concept of the application is to create a vector control ACIM driver with speed closed-loop, using a quadrature encoder coupled to the shaft. It serves as an example of a ACIM vector control system design using a Freescale microprocessor with the eTPU. -

DRV8308 Brushless DC Motor Controller

Product Order Technical Tools & Support & Folder Now Documents Software Community DRV8308 SLVSCF7B –FEBRUARY 2014–REVISED NOVEMBER 2017 DRV8308 Brushless DC Motor Controller 1 Features 3 Description The DRV8308 controls sensored brushless DC 1• Three-Phase Brushless DC Motor Controller motors with advanced features and a simple input – Digital Closed-Loop Speed Control with interface. As a predriver, it drives the gates of 6 Programmable Gain and Filters external N-Channel MOSFETs with a configurable • Drives 6 N-Channel MOSFETs With Configurable current of 10mA to 130mA for optimal switching 10- to 130-mA Gate Drive characteristics. • Integrated Commutation from Hall Sensors The 3 motor phases are commutated according to the – Timing Can Be Advanced/Delayed Hall sensor inputs. Once the motor reaches a – 120° or 180°-Sinusoidal Current Control consistent speed, the DRV8308 uses just 1 Hall sensor to minimize jitter caused by sensor mismatch. – Single Input Controls Motor Speed The Hall signal-to-drive timing can be advanced or • Operating Supply Voltage 8.5 to 32 V delayed in 0.1% increments to optimize power • Flexible Configuration Methods efficiency. An optional 180° commutation mode drives sinusoidal current through the motor and minimizes – Read Internal Non-Volatile Memory audible noise and torque ripple. Peak motor current – Read External EEPROM can be controlled by sizing a sense resistor. – Write SPI The DRV8308 achieves closed-loop speed control to • Configurable Motor Current Limiter spin motors to a precise RPM across a wide range of • 5-V Regulator for Hall Sensors load torques. The system matches motor speed—generated from an FG trace or the Hall • Low-power Standby Mode sensors—to the reference frequency on pin CLKIN.