Embryonic Origins of Hull Cells in the Flatworm Macrostomum Lignano Through Cell Lineage Analysis: Developmental and Phylogenetic Implications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

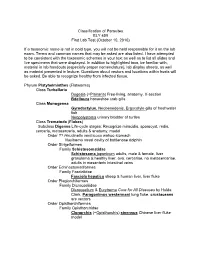

Classification of Parasites BLY 459 First Lab Test (October 10, 2010)

Classification of Parasites BLY 459 First Lab Test (October 10, 2010) If a taxonomic name is not in bold type, you will not be held responsible for it on the lab exam. Terms and common names that may be asked are also listed. I have attempted to be consistent with the taxonomic schemes in your text as well as to list all slides and live specimens that were displayed. In addition to highlighted taxa, be familiar with, material in lab handouts (especially proper nomenclature), lab display sheets, as well as material presented in lecture. Questions about vectors and locations within hosts will be asked. Be able to recognize healthy from infected tissue. Phylum Platyhelminthes (Flatworms) Class Turbellaria Dugesia (=Planaria ) Free-living, anatomy, X-section Bdelloura horseshoe crab gills Class Monogenea Gyrodactylus , Neobenedenis, Ergocotyle gills of freshwater fish Neopolystoma urinary bladder of turtles Class Trematoda ( Flukes ) Subclass Digenea Life-cycle stages: Recognize miracidia, sporocyst, redia, cercaria , metacercaria, adults & anatomy, model Order ?? Hirudinella ventricosa wahoo stomach Nasitrema nasal cavity of bottlenose dolphin Order Strigeiformes Family Schistosomatidae Schistosoma japonicum adults, male & female, liver granuloma & healthy liver, ova, cercariae, no metacercariae, adults in mesenteric intestinal veins Order Echinostomatiformes Family Fasciolidae Fasciola hepatica sheep & human liver, liver fluke Order Plagiorchiformes Family Dicrocoeliidae Dicrocoelium & Eurytrema Cure for All Diseases by Hulda Clark, Paragonimus -

Influence of Temperature on the Development, Reproduction and Regeneration in the Flatworm Model Organism Macrostomum Lignano

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/389478; this version posted August 10, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-ND 4.0 International license. Influence of temperature on the development, reproduction and regeneration in the flatworm model organism Macrostomum lignano Jakub Wudarski1, Kirill Ustyantsev2, Lisa Glazenburg1, Eugene Berezikov1* 1 European Research Institute for the Biology of Ageing, University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, Antonius Deusinglaan 1, 9713AV, Groningen, The Netherlands; 2 Institute of Cytology and Genetics, Prospekt Lavrentyeva 10, 630090, Novosibirsk, Russia. * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract The free-living marine flatworm Macrostomum lignano is a powerful model organism to study mechanisms of regeneration and stem cell regulation due to its convenient combination of biological and experimental properties, including the availability of transgenesis methods, which is unique among flatworm models. However, due to its relatively recent introduction in research, there are still many biological aspects of the animal that are not known. One of such questions is the influence of the culturing temperature on Macrostomum biology. Here we systematically investigated how different culturing temperatures affect the development time, reproduction rate, regeneration, heat shock response, and gene knockdown efficiency by RNA interference in M. lignano. We used marker transgenic lines of the flatworm to accurately measure the regeneration endpoint and to establish the stress response threshold for temperature shock. We found that compared to the culturing temperature of 20oC commonly used for M. -

Worms, Nematoda

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications from the Harold W. Manter Laboratory of Parasitology Parasitology, Harold W. Manter Laboratory of 2001 Worms, Nematoda Scott Lyell Gardner University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/parasitologyfacpubs Part of the Parasitology Commons Gardner, Scott Lyell, "Worms, Nematoda" (2001). Faculty Publications from the Harold W. Manter Laboratory of Parasitology. 78. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/parasitologyfacpubs/78 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Parasitology, Harold W. Manter Laboratory of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications from the Harold W. Manter Laboratory of Parasitology by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in Encyclopedia of Biodiversity, Volume 5 (2001): 843-862. Copyright 2001, Academic Press. Used by permission. Worms, Nematoda Scott L. Gardner University of Nebraska, Lincoln I. What Is a Nematode? Diversity in Morphology pods (see epidermis), and various other inverte- II. The Ubiquitous Nature of Nematodes brates. III. Diversity of Habitats and Distribution stichosome A longitudinal series of cells (sticho- IV. How Do Nematodes Affect the Biosphere? cytes) that form the anterior esophageal glands Tri- V. How Many Species of Nemata? churis. VI. Molecular Diversity in the Nemata VII. Relationships to Other Animal Groups stoma The buccal cavity, just posterior to the oval VIII. Future Knowledge of Nematodes opening or mouth; usually includes the anterior end of the esophagus (pharynx). GLOSSARY pseudocoelom A body cavity not lined with a me- anhydrobiosis A state of dormancy in various in- sodermal epithelium. -

Monophyly of Clade III Nematodes Is Not Supported by Phylogenetic Analysis of Complete Mitochondrial Genome Sequences

UC Davis UC Davis Previously Published Works Title Monophyly of clade III nematodes is not supported by phylogenetic analysis of complete mitochondrial genome sequences Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7509r5vp Journal BMC Genomics, 12(1) ISSN 1471-2164 Authors Park, Joong-Ki Sultana, Tahera Lee, Sang-Hwa et al. Publication Date 2011-08-03 DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-12-392 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Park et al. BMC Genomics 2011, 12:392 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2164/12/392 RESEARCHARTICLE Open Access Monophyly of clade III nematodes is not supported by phylogenetic analysis of complete mitochondrial genome sequences Joong-Ki Park1*, Tahera Sultana2, Sang-Hwa Lee3, Seokha Kang4, Hyong Kyu Kim5, Gi-Sik Min2, Keeseon S Eom6 and Steven A Nadler7 Abstract Background: The orders Ascaridida, Oxyurida, and Spirurida represent major components of zooparasitic nematode diversity, including many species of veterinary and medical importance. Phylum-wide nematode phylogenetic hypotheses have mainly been based on nuclear rDNA sequences, but more recently complete mitochondrial (mtDNA) gene sequences have provided another source of molecular information to evaluate relationships. Although there is much agreement between nuclear rDNA and mtDNA phylogenies, relationships among certain major clades are different. In this study we report that mtDNA sequences do not support the monophyly of Ascaridida, Oxyurida and Spirurida (clade III) in contrast to results for nuclear rDNA. Results from mtDNA genomes show promise as an additional independently evolving genome for developing phylogenetic hypotheses for nematodes, although substantially increased taxon sampling is needed for enhanced comparative value with nuclear rDNA. -

Helminthology Nematodes Strongyloides.Pdf

HelminthologyHelminthology –– NematodesNematodes StrongyloidesStrongyloides TerryTerry LL DwelleDwelle MDMD MPHTMMPHTM ClassificationClassification ofof NematodesNematodes Subclass Order Superfamily Genus and Species Probable (suborder) prevalence in man Secernentea Rhabditida Rhabditoidea Strongyloides stercoralis 56 million Stronglyloides myoptami Occasional Strongyloides fuelloborni Millions Strongyloides pyocyanis Occasional GeneralGeneral InformationInformation ► PrimarilyPrimarily aa diseasedisease ofof tropicaltropical andand subtropicalsubtropical areas,areas, highlyhighly prevalentprevalent inin Brazil,Brazil, Columbia,Columbia, andand SESE AsiaAsia ► ItIt isis notnot uncommonuncommon inin institutionalinstitutional settingssettings inin temperatetemperate climatesclimates ((egeg mentalmental hospitals,hospitals, prisons,prisons, childrenchildren’’ss homes)homes) ► SeriousSerious problemproblem inin thosethose onon immunosuppressiveimmunosuppressive therapytherapy ► HigherHigher prevalenceprevalence inin areasareas withwith aa highhigh waterwater tabletable GeneralGeneral RecognitionRecognition FeaturesFeatures ► Size;Size; parasiticparasitic femalefemale 2.72.7 mm,mm, freefree livingliving femalefemale 1.21.2 mm,mm, freefree livingliving malemale 0.90.9 mmmm ► EggsEggs –– 5050--5858 XX 3030--3434 umum ► TheThe RhabdiformRhabdiform larvaelarvae havehave aa shortershorter buccalbuccal canalcanal vsvs hookwormhookworm ► LarvaeLarvae havehave aa doubledouble laterallateral alaealae,, smallersmaller thanthan hookwormhookworm ► S.S. -

Some Immunological and Other Studies in Mice on Infection with Embryonated Eggs of Toxocara Canis (Werner, 1782)

This dissertation has been 69-11,668 microfilmed exactly as received MALIK, Prem Dutt, 1918- SOME IMMUNOLOGICAL AND OTHER STUDIES IN MICE ON INFECTION WITH EMBRYONATED EGGS OF TOXOCARA CANIS (WERNER, 1782). The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1968 Agriculture, animal pathology Health Sciences, immunology University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan SOME IMMUNOLOGICAL AND OTHER STUDIES IN MICE ON INFECTION WITH EMBRYONATED EGGS OF TOXOCARA CANIS (WERNER, 1782) DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Prem Dutt Malik, L.V.P., B.V.Sc., M.Sc ****** The Ohio State University 1968 Approved by Adviser / Department of Veterinary Parasitology ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to express my earnest thanks to my adviser, Dr. Fleetwood R. Koutz, Professor and Chairman, Department of Veterinary Parasitology, for planning a useful program of studies for me, and ably guiding my research project to a successful conclusion. His wide and varied experience in the field of Veterinary Parasitology came handy to me at all times during the conduct of this study. My grateful thanks are expressed to Dr. Harold F. Groves, for his sustained interest in the progress of this work, and careful scrutiny of the manuscript. Thanks are extended to Dr. Walter G. Venzke, for making improvements in the manuscript. Dr. Marion W. Scothorn deserves my thanks for his wholehearted cooperation. To Dr. Walter F. Loeb, I am really indebted for his valuable time in taking pictures of the eggs, the larvae, and the spermatozoa of Toxocara canis. The help of Mr. -

Entomopathogenic Nematodes (Nematoda: Rhabditida: Families Steinernematidae and Heterorhabditidae) 1 Nastaran Tofangsazi, Steven P

EENY-530 Entomopathogenic Nematodes (Nematoda: Rhabditida: families Steinernematidae and Heterorhabditidae) 1 Nastaran Tofangsazi, Steven P. Arthurs, and Robin M. Giblin-Davis2 Introduction Entomopathogenic nematodes are soft bodied, non- segmented roundworms that are obligate or sometimes facultative parasites of insects. Entomopathogenic nema- todes occur naturally in soil environments and locate their host in response to carbon dioxide, vibration, and other chemical cues (Kaya and Gaugler 1993). Species in two families (Heterorhabditidae and Steinernematidae) have been effectively used as biological insecticides in pest man- agement programs (Grewal et al. 2005). Entomopathogenic nematodes fit nicely into integrated pest management, or IPM, programs because they are considered nontoxic to Figure 1. Infective juvenile stages of Steinernema carpocapsae clearly humans, relatively specific to their target pest(s), and can showing protective sheath formed by retaining the second stage be applied with standard pesticide equipment (Shapiro-Ilan cuticle. et al. 2006). Entomopathogenic nematodes have been Credits: James Kerrigan, UF/IFAS exempted from the US Environmental Protection Agency Life Cycle (EPA) pesticide registration. There is no need for personal protective equipment and re-entry restrictions. Insect The infective juvenile stage (IJ) is the only free living resistance problems are unlikely. stage of entomopathogenic nematodes. The juvenile stage penetrates the host insect via the spiracles, mouth, anus, or in some species through intersegmental membranes of the cuticle, and then enters into the hemocoel (Bedding and Molyneux 1982). Both Heterorhabditis and Steinernema are mutualistically associated with bacteria of the genera Photorhabdus and Xenorhabdus, respectively (Ferreira and 1. This document is EENY-530, one of a series of the Department of Entomology and Nematology, UF/IFAS Extension. -

The Free-Living Flatworm Macrostomum Lignano

ARTICLE IN PRESS Experimental Gerontology xxx (2009) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Experimental Gerontology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/expgero Review The free-living flatworm Macrostomum lignano: A new model organism for ageing research Stijn Mouton a,*, Maxime Willems a, Bart P. Braeckman b, Bernhard Egger c, Peter Ladurner c, Lukas Schärer d, Gaetan Borgonie a a Nematology Unit, Department of Biology, Ghent University, Ledeganckstraat 35, 9000 Ghent, Belgium b Laboratory for Ageing Physiology and Molecular Evolution, Department of Biology, Ghent University, Ledeganckstraat 35, 9000 Ghent, Belgium c Ultrastructural Research and Evolutionary Biology, Institute of Zoology, University of Innsbruck, Technikerstrasse 25, 6020 Innsbruck, Austria d Evolutionary Biology, Zoological Institute, University of Basel, Vesalgasse 1, 4051 Basel, Switzerland article info abstract Article history: To study the several elements and causes of ageing, diverse model organisms and methodologies are Received 5 September 2008 required. The most frequently used models are Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Caenorhabditis elegans, Drosoph- Received in revised form 6 November 2008 ila melanogaster and rodents. All have their advantages and disadvantages and allow studying particular Accepted 28 November 2008 aspects of the ageing process. During the last few years, several ageing studies focussed on stem cells and Available online xxxx their role in tissue homeostasis. Here we present a new model organism which can study this relation where other model systems fail. The flatworm Macrostomum lignano possesses a dynamic population Keywords: of likely totipotent somatic stem cells known as neoblasts. Several characteristics qualify M. lignano as Flatworm a suitable model system for ageing studies in general and more specifically for gaining more insight in Macrostomum lignano Ageing the causal relation between stem cells, ageing and rejuvenation. -

Macrostomum Lignano Jakub Wudarski1, Kirill Ustyantsev2, Lisa Glazenburg1 and Eugene Berezikov1*

Wudarski et al. Zoological Letters (2019) 5:7 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40851-019-0122-6 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Influence of temperature on development, reproduction and regeneration in the flatworm model organism, Macrostomum lignano Jakub Wudarski1, Kirill Ustyantsev2, Lisa Glazenburg1 and Eugene Berezikov1* Abstract Background: The free-living marine flatworm Macrostomum lignano is a powerful model organism for use in studying mechanisms of regeneration and stem cell regulation due to its combination of biological and experimental properties, including the availability of transgenesis methods, which is unique among flatworm models. However, due to its relatively recent introduction in research, many aspects of this animal’s biology remain unknown. One such question is the influence of culture temperature on Macrostomum biology. Results: We systematically investigated how different culture temperatures affect development time, reproduction rate, regeneration, heat shock response, and gene knockdown efficiency by RNA interference (RNAi) in M. lignano. We used marker transgenic lines to accurately measure the regeneration endpoint, and to establish the stress response threshold for temperature shock. We found that compared to the culture temperature of 20 °C commonly used for M. lignano, temperatures of 25 °C–30 °C substantially increase the speed of development and regeneration, lead to faster manifestation of RNAi phenotypes, and increase reproduction rate without detectable negative consequences for the animal, while temperatures above 30 °C elicit a heat shock response. Conclusions: We show that altering temperature conditions can be used to reduce the time required to establish M. lignano cultures, perform RNAi experiments, store important lines, and optimize microinjection procedures for transgenesis. -

The Regenerative Flatworm Macrostomum Lignano, a Model

Int. J. Dev. Biol. 62: 551-558 (2018) https://doi.org/10.1387/ijdb.180077eb www.intjdevbiol.com The regenerative flatwormMacrostomum lignano, a model organism with high experimental potential STIJN MOUTON#, JAKUB WUDARSKI#, MAGDA GRUDNIEWSKA and EUGENE BEREZIKOV* European Research Institute for the Biology of Ageing, University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands ABSTRACT Understanding the process of regeneration has been one of the longstanding sci- entific aims, from a fundamental biological perspective, as well as within the applied context of regenerative medicine. Because regeneration competence varies greatly between organisms, it is essential to investigate different experimental animals. The free-living marine flatworm Macros- tomum lignano is a rising model organism for this type of research, and its power stems from a unique set of biological properties combined with amenability to experimental manipulation. The biological properties of interest include production of single-cell fertilized eggs, a transparent body, small size, short generation time, ease of culture, the presence of a pluripotent stem cell popula- tion, and a large regeneration competence. These features sparked the development of molecular tools and resources for this animal, including high-quality genome and transcriptome assemblies, gene knockdown, in situ hybridization, and transgenesis. Importantly, M. lignano is currently the only flatworm species for which transgenesis methods are established. This review summarizes -

The Biology of Strongyloides Spp.* Mark E

The biology of Strongyloides spp.* Mark E. Viney1§ and James B. Lok2 1School of Biological Sciences, University of Bristol, Bristol, BS8 1TQ, UK 2Department of Pathobiology, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104-6008, USA Table of Contents 1. Strongyloides is a genus of parasitic nematodes ............................................................................. 1 2. Strongyloides infection of humans ............................................................................................... 2 3. Strongyloides in the wild ...........................................................................................................2 4. Phylogeny, morphology and taxonomy ........................................................................................ 4 5. The life-cycle ..........................................................................................................................6 6. Sex determination and genetics of the life-cycle ............................................................................. 8 7. Controlling the life-cycle ........................................................................................................... 9 8. Maintaining the life-cycle ........................................................................................................ 10 9. The parasitic phase of the life-cycle ........................................................................................... 10 10. Life-cycle plasticity ............................................................................................................. -

Resistant Pseudosuccinea Columella Snails to Fasciola Hepatica (Trematoda) Infection in Cuba : Ecological, Molecular and Phenotypical Aspects Annia Alba Menendez

Comparative biology of susceptible and naturally- resistant Pseudosuccinea columella snails to Fasciola hepatica (Trematoda) infection in Cuba : ecological, molecular and phenotypical aspects Annia Alba Menendez To cite this version: Annia Alba Menendez. Comparative biology of susceptible and naturally- resistant Pseudosuccinea columella snails to Fasciola hepatica (Trematoda) infection in Cuba : ecological, molecular and phe- notypical aspects. Parasitology. Université de Perpignan; Instituto Pedro Kouri (La Havane, Cuba), 2018. English. NNT : 2018PERP0055. tel-02133876 HAL Id: tel-02133876 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-02133876 Submitted on 20 May 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Délivré par UNIVERSITE DE PERPIGNAN VIA DOMITIA En co-tutelle avec Instituto “Pedro Kourí” de Medicina Tropical Préparée au sein de l’ED305 Energie Environnement Et des unités de recherche : IHPE UMR 5244 / Laboratorio de Malacología Spécialité : Biologie Présentée par Annia ALBA MENENDEZ Comparative biology of susceptible and naturally- resistant Pseudosuccinea columella snails to Fasciola hepatica (Trematoda) infection in Cuba: ecological, molecular and phenotypical aspects Soutenue le 12 décembre 2018 devant le jury composé de Mme. Christine COUSTAU, Rapporteur Directeur de Recherche CNRS, INRA Sophia Antipolis M. Philippe JARNE, Rapporteur Directeur de recherche CNRS, CEFE, Montpellier Mme.