Social Networking Web Sites: Who Survives?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Architectures for Sustainable Social Networking

Supporting Kalyāṇamittatā Online: New Architectures for Sustainable Social Networking Paul Trafford Oxford, UK [email protected] 1-2 December 2010 3rd World Conference on Buddhism and Science 1 About these slides (version 1.0s for Slideshare) These slides are based on those that I used for a presentation entitled: Supporting Kalyāṇamittatā Online: New Architectures for Sustainable Social Networking given at the 3rd World Conference on Buddhism and Science ( http://www.wcbsthailand.com/ ) held 1-2 December 2010 at the College of Religious Studies, Mahidol University, Thailand. The slides are generally the same, except here I've inserted details of citations. Note also that some words use diacritics and were authored with the Times Ext Roman font. The content is provided under the Creative Commons License 2.0 Attribution 2.0 Generic. - Paul Trafford, Oxford. 1-2 December 2010 3rd World Conference on Buddhism and Science 2 Preface: School Friends "Paul"Paul doesn'tdoesn't havehave manymany friendsfriends butbut hehe hashas goodgood friends.”friends.” Teacher,Teacher, Parents'Parents' Evening,Evening, HagleyHagley FirstFirst SchoolSchool c.1977c.1977 1-2 December 2010 3rd World Conference on Buddhism and Science 3 Photo copyright © Hagley Community Association Overview of Presentation 1. Introduction 2. Approaches in Social Sciences: Well-being 3. Buddhist Architectures for Sustainable Relationships Online 4. Conclusions 1-2 December 2010 3rd World Conference on Buddhism and Science 4 Part 1: Introduction 1-2 December 2010 3rd World -

Everything You Need to Know About Internet Marketing

© Tourism Intelligence International www.tourism-intelligence.com Everything You Need to Know About Internet Marketing Market Intelligence Report www.Tourism-Intelligence.com Everything You Need to Know about Internet Marketing 1 www.tourism-intelligence.com © Tourism Intelligence International 2 Everything You Need to Know about Internet Marketing © Tourism Intelligence International www.tourism-intelligence.com Tourism Intelligence International is a leading research and consultancy company with offices in Germany and Trinidad. This report — Everything You Need to Know About Internet Marketing — is another in a series of tourism market analyses. Tourism Intelligence International is the publisher of Tourism Industry Intelligence, a monthly newsletter that provides analyses of and tracks the key trends and developments in the international travel and tourism industry, that is also available in Spanish. Other reports from Tourism Intelligence International include: Travel & Tourism’s Top Ten Emerging Markets €999.00 How Americans will Travel 2015 €1,299.00 How Germans will Travel 2015 €1,299.00 Everything you Need to Know about Internet Marketing €1,299.00 Sustainable Tourism Development – A Practical Guide for €1,299.00 Decision-Makers Successful Hotels and Resorts – Lessons from the Leaders €1,299.00 Successful Tourism Destinations – Lessons from the Leaders €1,299.00 The Impact of the Global Recession on Travel and Tourism €499.00 How the British will Travel 2015 €1,299.00 How the Japanese will Travel 2007 €799.00 Impact of Terrorism on World Tourism €499.00 Old but not Out – How to Win and Woo the Over 50s market €499.00 The ABC’s of Generation X, Y and Z Travellers €999.00 Tourism Intelligence International: German Office Trinidad Office An der Wolfskuhle 48 8 Dove Dr, P.O. -

Online-Buchhandel in Deutschland Die Buchhandelsbranche Vor Der Herausforderung Des Internet

Online-Buchhandel in Deutschland Die Buchhandelsbranche vor der Herausforderung des Internet Ulrich Riehm, Carsten Orwat und Bernd Wingert sind wissenschaftliche Mitarbeiter des Instituts für Technikfolgenabschätzung und Systemanaly- se (ITAS) des Forschungszentrums Karlsruhe. Kontakt: Forschungszentrum Karlsruhe, ITAS, Postfach 3640, 76021 Karlsruhe Tel.: 07247/82-2501, Fax: 07247/82-4806, E-Mail: [email protected] Die Projektseite im Internet lautet: http://www.itas.fzk.de/deu/projekt/pob.htm Die Studie zum Online-Buchhandel in Deutsch- land wurde durchgeführt im Auftrag der Akade- mie für Technikfolgenabschätzung in Baden- Württemberg, Stuttgart. Ulrich Riehm, Carsten Orwat, Bernd Wingert Online-Buchhandel in Deutschland Die Buchhandelsbranche vor der Herausforderung des Internet Forschungszentrum Karlsruhe Technik und Umwelt © Copyright 2001 Ulrich Riehm, Carsten Orwat, Bernd Wingert – Karlsruhe Überarbeitete und erweiterte Fassung des als Ar- beitsbericht Nr. 192 bei der Akademie für Tech- nikfolgenabschätzung in Baden-Württemberg unter gleichem Titel erschienen Berichts. Das Werk einschließlich aller seiner Teile ist ur- heberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung ist ohne Zustimmung der Autoren unzulässig. Das gilt insbesondere für Vervielfältigungen, Über- setzungen, Mikroverfilmungen, die Einspeiche- rung und Verarbeitung in elektronische Systeme, die körperliche und unkörperliche Wiedergabe am Bildschirm oder auf dem Wege der Daten- fernübertragung. Umschlaggestaltung: Nicole Gross, Forschungs- zentrum Karlsruhe Umschlagfoto: Markus Breig, Forschungs- zentrum Karlsruhe Bezugswege: Die gedruckte Ausgabe kann über jede stationäre wie Internet-Buchhandlung bezogen werden oder auch direkt bei Books on Demand GmbH, Norderstedt (http://www.bod.de). Die elektronischen Ausgaben, vollständig oder kapitelweise, zum Lesen am Bildschirm oder zum Ausdrucken auf dem Bürodrucker, sind erhält- lich über Spezialbuchläden für elektronische Bü- cher und bei allgemeinen Online-Buchläden: http://www.ciando.com, http://www.epodium.de, http://www.dibi.de, http://www.amazon.de. -

The Complete Guide to Social Media from the Social Media Guys

The Complete Guide to Social Media From The Social Media Guys PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Mon, 08 Nov 2010 19:01:07 UTC Contents Articles Social media 1 Social web 6 Social media measurement 8 Social media marketing 9 Social media optimization 11 Social network service 12 Digg 24 Facebook 33 LinkedIn 48 MySpace 52 Newsvine 70 Reddit 74 StumbleUpon 80 Twitter 84 YouTube 98 XING 112 References Article Sources and Contributors 115 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 123 Article Licenses License 125 Social media 1 Social media Social media are media for social interaction, using highly accessible and scalable publishing techniques. Social media uses web-based technologies to turn communication into interactive dialogues. Andreas Kaplan and Michael Haenlein define social media as "a group of Internet-based applications that build on the ideological and technological foundations of Web 2.0, which allows the creation and exchange of user-generated content."[1] Businesses also refer to social media as consumer-generated media (CGM). Social media utilization is believed to be a driving force in defining the current time period as the Attention Age. A common thread running through all definitions of social media is a blending of technology and social interaction for the co-creation of value. Distinction from industrial media People gain information, education, news, etc., by electronic media and print media. Social media are distinct from industrial or traditional media, such as newspapers, television, and film. They are relatively inexpensive and accessible to enable anyone (even private individuals) to publish or access information, compared to industrial media, which generally require significant resources to publish information. -

ENT 202 – Introduction to Entrepreneurial Ventures Is a Semester Course Work of 2 Credit Units

COURSE GUIDE ENT 202 INTRODUCTION TO ENTREPRENEURIAL VENTURES Course Team Dr. Cletus Akenbor – (Course Writer) Department of Business Administration Faculty of Management Sciences Federal University, Otuoke Prof. Bello Sabo - (Course Editor) Department of Business Administration Faculty of Administration Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria Dr. Lawal Kamaldeen A.A (H.O.D) Department of Entrepreneurial Studies Faculty of Management Sciences National Open University of Nigeria Dr. Timothy Ishola (Dean) Faculty of Management Sciences National Open University of Nigeria NATIONAL OPEN UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA 1 National Open University of Nigeria Headquarters University Village Plot 91 Cadastral Zone Nnamdi Azikiwe Expressway Jabi, Abuja. Lagos Office 14/16 Ahmadu Bello Way Victoria Island, Lagos e-mail: [email protected] URL: www.noun.edu.ng Published by: National Open University of Nigeria ISBN: Printed: 2017 All Rights Reserved 2 COURSE GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENT Introduction Course Content Course Aims Objectives Course Materials Study Units The Modules Assignment Assessment Summary 3 INTRODUCTION ENT 202 – Introduction to Entrepreneurial Ventures is a semester course work of 2 credit units. It is available to all students taking the B.Sc Entrepreneurship programme in the Department of Entrepreneurial Studies, Faculty of Management Sciences. The course consists of 13 units which cover the concept and y of organization success. The course guide tells you what ENT 202 is all about, the materials you will be using and how to make use of them. Other information includes the self assessment and tutor-marked questions. COURSE CONTENT The course content consists of entrepreneurial ventures COURSE AIMS The aim of this course is to expose: - understand the character of ventures - explain the long-term character of venture - explain the short – term character of venture 4.0. -

Music's On-Line Future Shapes up by Juliana Koranteng Line Music Market

ave semen JANUARY 22, 2000 Music Volume 17, Issue 4 Media. £3.95 W-411` talk -C41:30 rya dio M&M chart toppers this week Music's on-line future shapes up by Juliana Koranteng line music market. Also, the deal could untoward about one of the world's Eurochart Hot 100 Singles catapult Warner Music Group (WMG), media groups merging with the world's EIFFEL 65 LONDON - Last week's unexpectedTime Warner's music division, intomost successful on-line group," notes Move You Body takeover of Time Warner by on-linefrontrunner positioninthedigital New York -based Aram Sinnreich, ana- (Bliss Co.) giant America Online (AOL) not only delivery race among the five majors. lyst at Jupiter Communications. "It will European Top 100 Albums confirms the much predicted conver- The AOL/Time Warner merger help speed the adoption of on-line music immediatelyovershadowedother by consumers." Sinnreich adds that "It CELINE DION gence of old and new media, but also acknowledges the Internet as the importantdownloadable could even make or break a All The Way..A Decade of Song biggest influence on the future music deals announced band, which has not been (Epic/Columbia) growth of global music sales. A M ER ICA shortly beforehand byTI\IF. ARNFR done so far on the Internet. European Radio Top 50 According to analysts, Universal Music But AOL has the ability to CELINE DION shareholderandregulatory Group(UMG) andSony do so. As a well-known global brand, AOL's ambitions will be far-reaching. That's The Way It'Is approval of AOL/Time Warn- Music Entertainment (SME). -

How Innovation Works a Bright Future Not All Innovation Is Speeding up the Innovation Famine China’S Innovation Engine Regaining Momentum

Dedication For Felicity Bryan Contents Cover Title Page Dedication Introduction: The Infinite Improbability Drive 1. Energy Of heat, work and light What Watt wrought Thomas Edison and the invention business The ubiquitous turbine Nuclear power and the phenomenon of disinnovation Shale gas surprise The reign of fire 2. Public health Lady Mary’s dangerous obsession Pasteur’s chickens The chlorine gamble that paid off How Pearl and Grace never put a foot wrong Fleming’s luck The pursuit of polio Mud huts and malaria Tobacco and harm reduction 3. Transport The locomotive and its line Turning the screw Internal combustion’s comeback The tragedy and triumph of diesel The Wright stuff International rivalry and the jet engine Innovation in safety and cost 4. Food The tasty tuber How fertilizer fed the world Dwarfing genes from Japan Insect nemesis Gene editing gets crisper Land sparing versus land sharing 5. Low-technology innovation When numbers were new The water trap Crinkly tin conquers the Empire The container that changed trade Was wheeled baggage late? Novelty at the table The rise of the sharing economy 6. Communication and computing The first death of distance The miracle of wireless Who invented the computer? The ever-shrinking transistor The surprise of search engines and social media Machines that learn 7. Prehistoric innovation The first farmers The invention of the dog The (Stone Age) great leap forward The feast made possible by fire The ultimate innovation: life itself 8. Innovation’s essentials Innovation is gradual Innovation is different from invention Innovation is often serendipitous Innovation is recombinant Innovation involves trial and error Innovation is a team sport Innovation is inexorable Innovation’s hype cycle Innovation prefers fragmented governance Innovation increasingly means using fewer resources rather than more 9. -

Amazon, E-Commerce, and the New Brand World

AMAZON, E-COMMERCE, AND THE NEW BRAND WORLD by JESSE D’AGOSTINO A THESIS Presented to the Department of Business Administration and the Robert D. Clark Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts June 2018 An Abstract of the Thesis of Jesse D’Agostino for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in the Department of Business to be taken June 2018 Amazon, E-commerce, and the New Brand World Approved: _______________________________________ Lynn Kahle This thesis evaluates the impact of e-commerce on brands by analyzing Amazon, the largest e-commerce company in the world. Amazon’s success is dependent on the existence of the brands it carries, yet its business model does not support its longevity. This research covers the history of retail and a description of e-commerce in order to provide a comprehensive understanding of our current retail landscape. The history of Amazon as well as three business analyses, a PESTEL analysis, a Porter’s Five Forces analysis, and a SWOT analysis, are included to establish a cognizance of Amazon as a company. With this knowledge, several aspects of Amazon’s business model are illustrated as potential brand diluting forces. However, an examination of these forces revealed that there are positive effects of each of them as well. The two sided nature of these factors is coined as Amazon’s Collective Intent. After this designation, the Brand Matrix, a business tool, was created in order to mitigate Amazon’s negative influence on both brands and its future. ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank Professor Lynn Kahle, my primary thesis advisor, for guiding me through this process, encouraging me to question the accepted and giving me the confidence to know that I would find my stride over time. -

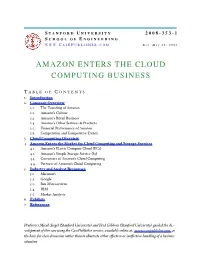

Amazon Enters the Cloud Computing Business

S T A N F O R D U NIVERSITY 2 0 0 8 - 3 5 3 - 1 S C H O O L O F E NGINEERING WWW.CASEP UBLISHER . COM Rev. May 20, 2008 AMAZON ENTERS THE CLOUD COMPUTING BUSINESS T A B L E O F C ONTENTS 1. Introduction 2. Company Overview 2.1. The Founding of Amazon 2.2. Amazon’s Culture 2.3. Amazon’s Retail Business 2.4. Amazon’s Other Services & Products 2.5. Financial Performance of Amazon 2.6. Competition and Competitive Trends 3. Cloud Computing Overview 4. Amazon Enters the Market for Cloud Computing and Storage Services 4.1. Amazon’s Elastic Compute Cloud (EC2) 4.2. Amazon’s Simple Storage Service (S3) 4.3. Customers of Amazon’s Cloud Computing 4.4. Partners of Amazon’s Cloud Computing 5. Industry and Analyst Responses 5.1. Microsoft 5.2. Google 5.3. Sun Microsystem 5.4. IBM 5.5. Market Analysts 6. Exhibits 7. References Professors Micah Siegel (Stanford University) and Fred Gibbons (Stanford University) guided the de- velopment of this case using the CasePublisher service, available online at www.casepublisher.com as the basis for class discussion rather than to i)ustrate either e*ective or ine*ective handling of a business situation. 2008-353-1 Amazon Enters the Cloud Computing Business I NTRODUCTION Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos looked at the clock on the instrument panel of his Segway Human Transporter; it was 7:52AM and he knew he would need a little luck to get to his 8:00AM meeting at Amazon's Beacon Hill headquarters. -

![(12) Umted States Patent (10) Patent N6.= US 8,015,119 B2 Buyukkokten Et A]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7453/12-umted-states-patent-10-patent-n6-us-8-015-119-b2-buyukkokten-et-a-3887453.webp)

(12) Umted States Patent (10) Patent N6.= US 8,015,119 B2 Buyukkokten Et A]

US008015119B2 (12) Umted States Patent (10) Patent N6.= US 8,015,119 B2 Buyukkokten et a]. (45) Date of Patent: Sep. 6, 2011 (54) METHODS AND SYSTEMS FOR THE 6,061,681 A 5/2000 Collins DISPLAY AND NAVIGATION OF A SOCIAL 6,073,105 A 6/2000 sutgllffe 9t a1~ NETWORK 6,073,138 A 6/2000 del EtraZ et a1. 6,092,049 A 7/2000 Chlslenko et al. _ _ 6,185,559 B1 2/2001 Brin et a1. (75) Inventors: Orkut Buyukkokten, Mounta1n V1eW, 6,256,643 B1 7/2001 Hill et a1, CA (US); Adam Douglas Smith, 6,285,999 B1 9/2001 Page Mountain View CA (Us) 6,327,590 B1 12/2001 Chidlovskii ’ 6,366,962 B1 4/2002 Teibel (73) Assignee: Google Inc., Mountain View, CA (US) 6’389’372 Bl 5/2002 Glance et a1‘ (Continued) ( * ) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this patent is extended or adjusted under 35 FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS U.S.C. 154(b) by 121 days. JP 11265369 9/1999 C t' d (21) Appl. NO.Z 10/928,654 ( on “me ) (22) F1led:. Aug. 26, 2004 OTHER PUBLICATIONS Amazon.com, “Feedback FAQ” Web page at http://WWWamaZon. (65) Prior Publication Data com/exec/obidos/tg/br0Wse/-/1161284/qid:1091110289/sr:1-1/ Us Zoos/0159970 A1 Jul‘ 21 2005 002-2, as available via the Internet and printed on Jul. 29, 2004. Related U.S. Appllcatlon_ _ Data (Continued) (60) Provisional application No. 60/538,035, ?led on Jan. P 1’ imary Examiner * Jonathan Ouenette 21s 2004_ (74) Attorney, Agent, or Firm * Patent LaW Works LLP (51) Int. -

Eartl^Lmatters Pages 14 - 17 ^"^ This Week's Special Section

. "waa ^._- ;»:.^,:t;T^ '^^- Established 1971 http://etcetera.humberc.on.ca \my r j-iUif Get Lifestyles Entertai Fun lovin' criminals Quintet jazzes /pg20 Bistro / pg 22 vol. 26 issue 22 March 19-25, 1998 Insidi Oh Boy-er! */' Tracy Boyer feelin' or not fell to the chief returning officer, former SAC president buoyant as she says Loreen Ramsuchit, who did not allow anything other than the hello to SAC Prez "x" Spoiled ballots or not, the position results would have remained the same. Boyer had 26 spoiled bal- BY Corey Keegan lots and Dhaliwal 38. News Reporter "Maybe I didn't reach enough Despite a contention over bal- students," said Dhaliwal, who lot marking, and low voter turn was disappointed with the result. out, Tracy Boyer won the SAC "\ wish Tracy all the best," said North presidential election by 71 Dhaliwal who plans to remain votes against current vice-presi- active with SAC. dent Nikki Dhaliwal. Boyer said she felt confident Bell elected vice- Kenn was throughout the campaign. "I've president, defeating Kim ;PORTl had a lot of good feedback from Thompson and Jayme Marji. students, even students I didn't Boyer won 295 of the 519 know. That was very encourag- acceptable ballots cast. Dhaliwal ing," said Boyer. Being easy to gained only 224. t/ talk to made the difference, r?^^' Before the votes were counted according to Boyer. "I'm very there was some dispute as to good at being diplomatic ... and whether ballots marked with a interacting with all sorts of peo- check mark would be counted as ple,"said the busi- second-year fMOTO BY COMT KEEGAN well as those marked properly (--' ness markehng student. -

French Language DRS Parsing Ngoc Luyen Le

French language DRS parsing Ngoc Luyen Le To cite this version: Ngoc Luyen Le. French language DRS parsing. Computation and Language [cs.CL]. Ecole nationale supérieure Mines-Télécom Atlantique, 2020. English. NNT : 2020IMTA0202. tel-03132658 HAL Id: tel-03132658 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-03132658 Submitted on 5 Feb 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. THÈSE DE DOCTORAT DE L’ÉCOLE NATIONALE SUPÉRIEURE MINES-TELECOM ATLANTIQUE BRETAGNE PAYS DE LA LOIRE - IMT ATLANTIQUE Ecole Doctorale N°601 Mathèmatique et Sciences et Technologies de l’Information et de la Communication Spécialité : Informatique Par Ngoc Luyen LE French Language DRS Parsing Thèse présentée et soutenue à PLOUZANÉ, le 15 septembre 2020 Unité de recherche : Lab-STICC UMR 6285 - CNRS Thèse N° : 2020IMTA0202 Rapporteurs avant soutenance : Panayota Tita Kyriacopoulou Professeure des universités, Université Gustave Eiffel Benoît Crabbé Professeur, Université Paris Diderot & Institut Universitaire de France Composition du jury : Président : Ismaïl Biskri Professeur, Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières Examinateur : Panayota Tita Kyriacopoulou Professeure des universités, Université Gustave Eiffel Benoît Crabbé Professeur, Université Paris Diderot & Institut Universitaire de France Annie Forêt Maître de Conféfrences HDR, IRISA-ISTIC Dir.