Key Factors That Contributed to the Guitar Developing Into a Solo Instrument in the Early 19 Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

17 June 2011 / 15 Sivan, 5771 Volume 15 Number 22 Israel Looking to Increasing Its Investment in Africa PAGE 8

www.sajewishreport.co.za Friday, 17 June 2011 / 15 Sivan, 5771 Volume 15 Number 22 Israel looking to increasing its investment in Africa PAGE 8 In a reflective mood. South Africa last Saturday bade farewell to Mama Albertina Sisulu at the Orlando Stadium in Soweto. She died at age 92 and was laid to rest in the Newclare Cemetery in Johannesburg, next to her late husband, Walter. This hero of the Struggle, who A NATION always fearlessly spoke her mind, retained a dignity throughout her long life. Pictured at the funeral ceremony (front row) are Philip Chauke, driver to former Chief Justice Arthur Chaskalson; Alexi Bizos, son of Struggle lawyer Advocate George Bizos; George Bizos; and MOURNS Arthur Chaskalson. Bizos and Chaskalson both played key roles in the legal fight against apartheid. (PHOTOGRAPH: ILAN OSSENDRYVER) FREUND: Israel’s ‘Battered Habonim ideologues EU rabbis urge Arab Hobbies, collectables Nation Syndrome’ / 9 of yore take stock / 11 Spring to continue / 5 & recreation / 12-17 YOUTH / 20 SPORT / 24 LETTERS / 18-19 CROSSWORD & SUDOKU / 22 COMMUNITY BUZZ / 6 WHAT’S ON / 22 2 SA JEWISH REPORT 17 - 24 June 2011 SHABBAT TIMES PARSHA OF THE WEEK June 17/15 Sivan It’s Absa Jewish Achievers’ June 18/16 Sivan The Invisibility Cloak Shelach barmitzvah this year Starts Ends PETER FELDMAN on the African continent, recognise and 17:06 17:58 Johannesburg share the goals this year of these achievers PARSHAT THE COUNTDOWN has begun for the Absa to strengthen the fabric of our community.” 17:26 18:21 Cape Town Jewish Achiever Awards 2011, an annual The Helen Suzman Lifetime Achiever 16:46 17:39 Durban SHELACH Rabbi Danny Sackstein highlight of the Jewish business and social Award is given to a member of the Jewish 17:07 18:00 Bloemfontein calendar. -

52183 FRMS Cover 142 17/08/2012 09:25 Page 1

4884 cover_52183 FRMS cover 142 17/08/2012 09:25 Page 1 Autumn 2012 No. 157 £1.75 Bulletin 4884 cover_52183 FRMS cover 142 17/08/2012 09:21 Page 2 NEW RELEASES THE ROMANTIC VIOLIN STEPHEN HOUGH’S CONCERTO – 13 French Album Robert Schumann A master pianist demonstrates his Hyperion’s Romantic Violin Concerto series manifold talents in this delicious continues its examination of the hidden gems selection of French music. Works by of the nineteenth century. Schumann’s late works Poulenc, Fauré, Debussy and Ravel rub for violin and orchestra had a difficult genesis shoulders with lesser-known gems by but are shown as entirely worthy of repertoire their contemporaries. status in these magnificent performances by STEPHEN HOUGH piano Anthony Marwood. ANTHONY MARWOOD violin CDA67890 BBC SCOTTISH SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA CDA67847 DOUGLAS BOYD conductor MUSIC & POETRY FROM THIRTEENTH-CENTURY FRANCE Conductus – 1 LOUIS SPOHR & GEORGE ONSLOW Expressive and beautiful thirteenth-century vocal music which represents the first Piano Sonatas experiments towards polyphony, performed according to the latest research by acknowledged This recording contains all the major works for masters of the repertoire. the piano by two composers who were born within JOHN POTTER tenor months of each other and celebrated in their day CHRISTOPHER O’GORMAN tenor but heard very little now. The music is brought to ROGERS COVEY-CRUMP tenor modern ears by Howard Shelley, whose playing is the paradigm of the Classical-Romantic style. HOWARD SHELLEY piano CDA67947 CDA67949 JOHANNES BRAHMS The Complete Songs – 4 OTTORINO RESPIGHI Graham Johnson is both mastermind and Violin Sonatas pianist in this series of Brahms’s complete A popular orchestral composer is seen in a more songs. -

Mark Hilliard Wilson St

X ST. JAMES CATHEDRAL X SEATTLE X 3 SEPTEMBER 2021 X 6:30 PM X MUSICAL PRAYER mark hilliard wilson St. James Cathedral Guitarist “Méditation” from Thaïs Jules Massenet 1842–1912 Etude No. 10 from 12 Etudes, Op. 6 Fernando Sor c. 1778–1839 Ave Maria Franz Schubert 1797–1828 Simple Gifts Joseph Brackett 1797–1882 Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring Johann Sebastian Bach 1685–1750 Gymnopédie No. 1 from Trois Gymnopédies Erik Satie 1866–1925 Nigbati Iya Mi Ba Reriin Taiwo Adegoke “When my mother laughs” birth year unknown Theme from second movement ofNew World Symphony Antonín Dvořák 1841–1904 Prelude No. 1 in C Major from The Well-Tempered Clavier, BWV 846 J. S. Bach Woven World Andrew York b. 1958 Classical guitarist Mark Hilliard Wilson curates programs that explore the experiences of the heart through the ages, hoping to share some insight and reflection on our common humanity. He brings joy and technical finesse to the listener while integrating music from diverse backgrounds and different ages with a compelling story and a wry sense of humor. Performing regularly at festivals and concert series, Wilson has distinguished himself as a unique voice with programs that feature his own transcriptions of both the well-known and the obscure. Wilson’s compositions for the guitar have been appearing on stages throughout the Northwest US and Canada for over 15 years. He works in is the relatively unexplored genre of an ensemble of multiple guitars as the conductor, composer, arranger, and music director to the Guitar Orchestra of Seattle. Wilson has taught at Whatcom Community College and Bellevue College. -

Soundboardindexnames.Txt

SoundboardIndexNames.txt Soundboard Index - List of names 03-20-2018 15:59:13 Version v3.0.45 Provided by Jan de Kloe - For details see www.dekloe.be Occurrences Name 3 A & R (pub) 3 A-R Editions (pub) 2 A.B.C. TV 1 A.G.I.F.C. 3 Aamer, Meysam 7 Aandahl, Vaughan 2 Aarestrup, Emil 2 Aaron Shearer Foundation 1 Aaron, Bernard A. 2 Aaron, Wylie 1 Abaca String Band 1 Abadía, Conchita 1 Abarca Sanchis, Juan 2 Abarca, Atilio 1 Abarca, Fernando 1 Abat, Joan 1 Abate, Sylvie 1 ABBA 1 Abbado, Claudio 1 Abbado, Marcello 3 Abbatessa, Giovanni Battista 1 Abbey Gate College (edu) 1 Abbey, Henry 2 Abbonizio, Isabella 1 Abbott & Costello 1 Abbott, Katy 5 ABC (mag) 1 Abd ar-Rahman II 3 Abdalla, Thiago 5 Abdihodzic, Armin 1 Abdu-r-rahman 1 Abdul Al-Khabyyr, Sayyd 1 Abdula, Konstantin 3 Abe, Yasuo 2 Abe, Yasushi 1 Abel, Carl Friedrich 1 Abelard 1 Abelardo, Nicanor 1 Aber, A. L. 4 Abercrombie, John 1 Aberle, Dennis 1 Abernathy, Mark 1 Abisheganaden, Alex 11 Abiton, Gérard 1 Åbjörnsson, Johan 1 Abken, Peter 1 Ablan, Matthew 1 Ablan, Rosilia 1 Ablinger, Peter 44 Ablóniz, Miguel 1 Abondance, Florence & Pierre 2 Abondance, Pierre 1 Abraham Goodman Auditorium 7 Abraham Goodman House 1 Abraham, Daniel 1 Abraham, Jim 1 Abrahamsen, Hans Page 1 SoundboardIndexNames.txt 1 Abrams (pub) 1 Abrams, M. H. 1 Abrams, Richard 1 Abrams, Roy 2 Abramson, Robert 3 Abreu 19 Abreu brothers 3 Abreu, Antonio 3 Abreu, Eduardo 1 Abreu, Gabriel 1 Abreu, J. -

Download Download

МUSIC SUMMER FESTIVALS AS PROMOTERS OF THE SPA CULTURAL TOURISM: FESTIVAL OF CLASSICAL MUSIC VRNJCI Smiljka Isaković1, Jelena Borović-Dimić2 Abstract This paper is dedicated to the music summer festivals, a hallmark of the local community and the holder of the economic development of the region and the society, from ancient times to the present day. Special emphasis is placed on the International Festival of classical music "Vrnjci", held in Belimarković mansion in July, organized by the Homeland Мuseum – Castle of Culture of Vrnjaĉka Banja. A dramatic development of high technologies brought forth a new era based on conceptual creativity. Leisure time is prolonged, while tourism as one of the activities of spending leisure time is changing from passive to active. The cultural sector is becoming an important partner in the economic development of countries and cultural tourism is gaining in importance. Festival tourism in this country must be supported by the wider community and the state because the quality of cultural events makes us an equal competitor on the global tourism market. Keywords: cultural tourism, festivals, art, music, local self governments. Cultural Tourism The middle of the nineteenth and the twentieth centuries can be called the period of tourism, since Stendhal popularized this term in France with his book "Memoirs of a tourist" (1838) and Englishman Thomas Cook opened his travel agency in 1841. Modern tourism experienced its first expansion between 1850 and 1870, enabled by the major railways networking in Europe -

Register of Sports Contacts with South Africa, 1 April - 31 December 1981

Register of Sports Contacts with South Africa, 1 April - 31 December 1981 http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.nuun1982_07 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org Register of Sports Contacts with South Africa, 1 April - 31 December 1981 Alternative title Notes and Documents - United Nations Centre Against ApartheidNo. 7/82 Author/Creator United Nations Centre against Apartheid; United Nations Special Committee Against Apartheid Publisher United Nations, New York Date 1982-02-00 Resource type Reports Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) South Africa Coverage (temporal) 1981 Source Northwestern University Libraries Description The Special Committee published this report on 1 March 1982, which contains the second register of sports contacts with South Africa, covering the period from 1 April to 31 December 1981. -

Inhalt / Contents

Inhalt / Contents Grußwort / Greeting........................................... 7 II - Psalmvertonungen und Gebete / Vorwort / Preface................................................ 9 Psalm Settings and Prayers.............. 49 Ganz Europa im Fokus • Die Auswahl als repräsentativer Zeitspiegel und abgestimmt auf die heutige Praxis • Dominus regit m e.................................................. 50 Zur Gliederung der Chorstücke - Ein reichhaltiges Chorreper Carl Nielsen (1865-1931) toire • A cappella oder mit Begleitung? • Zur Interpretation - W ie der Hirsch schreiet / As the Hart Panteth.......... 58 Geistliche Chormusik im „langen 19. Jahrhundert" • Zur Heinrich Bellermann (1832-1903) Verwendung des Romantik-Begriffs im Titel des Chorbuchs • Editorische Anmerkungen - Zu den verwendeten Bibel Sicut cervus........................................................... 64 versionen • Hilfestellungen für die Probenarbeit Charles Gounod (1818-1893) All of Europe in the limelight • The selection as a represen Kot po mrzli studencini / As the Thirsting Hart Pants.. 67 tative reflection of the times, yet in tune with modern Hugolin Sattner (1851-1934) practice - The organisation of the choral pieces • A rich Sende dein Licht (Kanon) / and extensive choral repertoire • A cappella or with accom Send Out Thy Light (Canon)............................... 68 paniment? • Concerning performance • Sacred choral music Friedrich Schneider (1786-1853) in the "long nineteenth century" • On the use of the term "Romantik" in the title of this choir -

The Role of Small Private Game Reserves in Leopard Panthera Pardus and Other Carnivore Conservation in South Africa

The role of small private game reserves in leopard Panthera pardus and other carnivore conservation in South Africa Tara J. Pirie Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of The University of Reading for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Biological Sciences November 2016 Acknowledgements I would first like to thank my supervisors Professor Mark Fellowes and Dr Becky Thomas, without whom this thesis would not have been possible. I am sincerely grateful for their continued belief in the research and my ability and have appreciated all their guidance and support. I especially would like to thank Mark for accepting this project. I would like to acknowledge Will & Carol Fox, Alan, Lynsey & Ronnie Watson who invited me to join Ingwe Leopard Research and then aided and encouraged me to utilize the data for the PhD thesis. I would like to thank Andrew Harland for all his help and support for the research and bringing it to the attention of the University. I am very grateful to the directors of the Protecting African Wildlife Conservation Trust (PAWct) and On Track Safaris for their financial support and to the landowners and participants in the research for their acceptance of the research and assistance. I would also like to thank all the Ingwe Camera Club members; without their generosity this research would not have been possible to conduct and all the Ingwe Leopard Research volunteers and staff of Thaba Tholo Wilderness Reserve who helped to collect data and sort through countless images. To Becky Freeman, Joy Berry-Baker -

INTEGRATED ANNUAL REPORT 2013 About This Report

INTEGRATED ANNUAL REPORT 2013 About this report This integrated annual report presents Attacq Limited’s financial, operational, social and environmental performance for the 2013 financial year. The Company obtained formal approval from the JSE to list on 14 October 2013, therefore this is the Company’s first integrated report. Integrated reporting is a process and we acknowledge some areas might require improvement and/or refinement, and we are working towards producing a more integrated report in the future. The Company reports in accordance with International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) and the South African Companies Act 71, of 2008. As far as possible, the Company has applied the principles contained in the King Report on Corporate Governance for South Africa 2009 (King III). The content of this report is intended to provide stakeholders with the information necessary to evaluate the Company’s performance over the past year and to assess its ability to create and sustain value in the short, medium and long term. The 2013 financial year refers to the period from 1 July 2012 to 30 June 2013. Attacq will be listed on the JSE in South Africa under the share code ATT and the Company reports in line with the JSE’s Listings Requirements. This integrated annual report contains forward looking statements that, unless otherwise indicated, reflect the Company’s expectations as at 30 June 2013. Actual results may differ materially from the Company’s expectations if known and unknown risks or uncertainties affect its business, or if estimates or assumptions prove inaccurate. The Company cannot guarantee that any forward looking statement will materialise and, accordingly, readers are cautioned not to place undue reliance on any forward looking statements. -

Classic Choices April 6 - 12

CLASSIC CHOICES APRIL 6 - 12 PLAY DATE : Sun, 04/12/2020 6:07 AM Antonio Vivaldi Violin Concerto No. 3 6:15 AM Georg Christoph Wagenseil Concerto for Harp, Two Violins and Cello 6:31 AM Guillaume de Machaut De toutes flours (Of all flowers) 6:39 AM Jean-Philippe Rameau Gavotte and 6 Doubles 6:47 AM Ludwig Van Beethoven Consecration of the House Overture 7:07 AM Louis-Nicolas Clerambault Trio Sonata 7:18 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Divertimento for Winds 7:31 AM John Hebden Concerto No. 2 7:40 AM Jan Vaclav Vorisek Sonata quasi una fantasia 8:07 AM Alessandro Marcello Oboe Concerto 8:19 AM Franz Joseph Haydn Symphony No. 70 8:38 AM Darius Milhaud Carnaval D'Aix Op 83b 9:11 AM Richard Strauss Der Rosenkavalier: Concert Suite 9:34 AM Max Reger Flute Serenade 9:55 AM Harold Arlen Last Night When We Were Young 10:08 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Exsultate, Jubilate (Motet) 10:25 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony No. 3 10:35 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Piano Concerto No. 10 (for two pianos) 11:02 AM Johannes Brahms Symphony No. 4 11:47 AM William Lawes Fantasia Suite No. 2 12:08 PM John Ireland Rhapsody 12:17 PM Heitor Villa-Lobos Amazonas (Symphonic Poem) 12:30 PM Allen Vizzutti Celebration 12:41 PM Johann Strauss, Jr. Traumbild I, symphonic poem 12:55 PM Nino Rota Romeo & Juliet and La Strada Love 12:59 PM Max Bruch Symphony No. 1 1:29 PM Pr. Louis Ferdinand of Prussia Octet 2:08 PM Muzio Clementi Symphony No. -

Musina Mall Redevelopment

2018 / NO 34 WWW.MOOLMANGROUP.CO.ZA MUSINA MALL REDEVELOPMENT With over 95 000 customers visiting the mall over the opening weekend, it was hardly a surprise that Musina Mall was selected as one of the SACSC finalists in the Redevelopment Category. Located in the heart of the heritage-rich town of Musina, Musina The new development includes national retailers such as Checkers, Mall officially opened its doors on 30 March 2017. Redeveloped by Edgars, Truworths, Identity, Pick n Pay Clothing, Studio 88 and John leading property developers and investors, Moolman Group and Craig, all new entries to Musina. The mall also houses all five major Investec Property Fund, the new centre incorporated a complete banks: ABSA, Standard Bank, Nedbank, FNB and Capitec. revamp of Great North Plaza. This investment is set to meet the high demand for shopping and trading opportunities; not only to people living in Musina, but over The mall boasts 35 090 m² (30 267 m² Musina Mall and 4 823 m² Great the Beitbridge border and into Zimbabwe as well. North Plaza) of retail space anchored by Checkers and Shoprite, with a host of new stores creating an exciting new and improved tenant mix – including groceries, fashion, services, health, beauty and food. Musina Mall offers unparalleled convenience to residents of this prominent business, social and tourist node. There was a strong demand from retailers to partake in the addition of the mall, based on current trading conditions in Musina. FROM THE TOP DESK AT THE COALFACE UK INVESTMENTS: In our previous issue we focussed on the 50 year celebration of the I’m honoured to have received a “Page 2 Column”. -

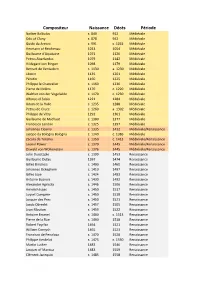

Compositeur Naissance Décès Période Notker Balbulus C

Compositeur Naissance Décès Période Notker Balbulus c. 840 912 Médiévale Odo of Cluny c. 878 942 Médiévale Guido da Arezzo c. 991 c. 1033 Médiévale Hermann of Reichenau 1013 1054 Médiévale Guillaume d'Aquitaine 1071 1126 Médiévale Petrus Abaelardus 1079 1142 Médiévale Hildegard von Bingen 1098 1179 Médiévale Bernart de Ventadorn c. 1130 a. 1230 Médiévale Léonin 1135 1201 Médiévale Pérotin 1160 1225 Médiévale Philippe le Chancelier c. 1160 1236 Médiévale Pierre de Molins 1170 c. 1220 Médiévale Walther von der Vogelwide c. 1170 c. 1230 Médiévale Alfonso el Sabio 1221 1284 Médiévale Adam de la Halle c. 1235 1288 Médiévale Petrus de Cruce c. 1260 a. 1302 Médiévale Philippe de Vitry 1291 1361 Médiévale Guillaume de Machaut c. 1300 1377 Médiévale Francesco Landini c. 1325 1397 Médiévale Johannes Ciconia c. 1335 1412 Médiévale/Renaissance Jacopo da Bologna Bologna c. 1340 c. 1386 Médiévale Zacara da Teramo c. 1350 c. 1413 Médiévale/Renaissance Leonel Power c. 1370 1445 Médiévale/Renaissance Oswald von Wolkenstein c. 1376 1445 Médiévale/Renaissance John Dunstaple c. 1390 1453 Renaissance Guillaume Dufay 1397 1474 Renaissance Gilles Binchois c. 1400 1460 Renaissance Johannes Ockeghem c. 1410 1497 Renaissance Gilles Joye c. 1424 1483 Renaissance Antoine Busnois c. 1430 1492 Renaissance Alexander Agricola c. 1446 1506 Renaissance Heinrich Isaac c. 1450 1517 Renaissance Loyset Compère c. 1450 1518 Renaissance Josquin des Prez c. 1450 1521 Renaissance Jacob Obrecht c. 1457 1505 Renaissance Jean Mouton c. 1459 1522 Renaissance Antoine Brumel c. 1460 c. 1513 Renaissance Pierre de la Rue c. 1460 1518 Renaissance Robert Fayrfax 1464 1521 Renaissance William Cornysh 1465 1523 Renaissance Francisco de Penalosa c.