Amicus Briefs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federal Rules of Evidence: 801-03, 901

FEDERAL RULES OF EVIDENCE: 801-03, 901 Rule 801. Definitions The following definitions apply under this article: (a) Statement. A "statement" is (1) an oral or written assertion or (2) nonverbal conduct of a person, if it is intended by the person as an assertion. (b) Declarant. A "declarant" is a person who makes a statement. (c) Hearsay. "Hearsay" is a statement, other than one made by the declarant while testifying at the trial or hearing, offered in evidence to prove the truth of the matter asserted. (d) Statements which are not hearsay. A statement is not hearsay if-- (1) Prior statement by witness. The declarant testifies at the trial or hearing and is subject to cross- examination concerning the statement, and the statement is (A) inconsistent with the declarant's testimony, and was given under oath subject to the penalty of perjury at a trial, hearing, or other proceeding, or in a deposition, or (B) consistent with the declarant's testimony and is offered to rebut an express or implied charge against the declarant of recent fabrication or improper influence or motive, or (C) one of identification of a person made after perceiving the person; or (2) Admission by party-opponent. The statement is offered against a party and is (A) the party's own statement, in either an individual or a representative capacity or (B) a statement of which the party has manifested an adoption or belief in its truth, or (C) a statement by a person authorized by the party to make a statement concerning the subject, or (D) a statement by the party's agent or servant concerning a matter within the scope of the agency or employment, made during the existence of the relationship, or (E) a statement by a coconspirator of a party during the course and in furtherance of the conspiracy. -

V Proof of Residence for Voter Registration

v Proof Of Residence For Voter Registration What Do I Need To Know About Proof Of Residence For Voter Registration? A Proof of Residence document is a document that proves where you live in Wisconsin and is only used when registering to vote. Photo ID is separate, you only show photo ID to prove who you are when you request an absentee ballot or receive a ballot at your polling place. When Do I Have To Provide Proof Of Residence? All voters MUST provide a Proof of Residence Document. If you register to vote by mail, in-person in your clerk’s office, with a Election Registration Official, or at your polling place on Election Day, you need to provide a Proof of Residence document. * If you are an active military voter, or a permanent overseas voter (with no intent to return to the U.S.) you do not need to provide a Proof of Residence document. What Documents Can I Use As Proof Of Residence For Registering? All Proof of Residence documents must include the voter’s name and current residential address. • A current and valid State of Wisconsin Driver License or State ID card. • Any other official identification card or license issued by a Wisconsin governmental body or unit. • Any identification card issued by an employer in the normal course of business and bearing a photo of the card holder, but not including a business card. • A real estate tax bill or receipt for the current year or the year preceding the date of the election. • A university, college, or technical college identification card (must include photo) ONLY if the voter provides a fee receipt dated within the last 9 months or the institution provides a certified housing list, that indicates citizenship, to the municipal clerk. -

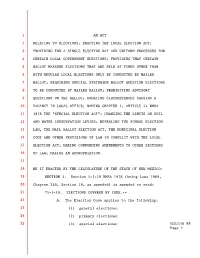

Local Election Act;

1 AN ACT 2 RELATING TO ELECTIONS; ENACTING THE LOCAL ELECTION ACT; 3 PROVIDING FOR A SINGLE ELECTION DAY AND UNIFORM PROCESSES FOR 4 CERTAIN LOCAL GOVERNMENT ELECTIONS; PROVIDING THAT CERTAIN 5 BALLOT MEASURE ELECTIONS THAT ARE HELD AT TIMES OTHER THAN 6 WITH REGULAR LOCAL ELECTIONS ONLY BE CONDUCTED BY MAILED 7 BALLOT; REQUIRING SPECIAL STATEWIDE BALLOT QUESTION ELECTIONS 8 TO BE CONDUCTED BY MAILED BALLOT; PROHIBITING ADVISORY 9 QUESTIONS ON THE BALLOT; UPDATING CIRCUMSTANCES CAUSING A 10 VACANCY IN LOCAL OFFICE; NAMING CHAPTER 1, ARTICLE 24 NMSA 11 1978 THE "SPECIAL ELECTION ACT"; CHANGING THE LIMITS ON SOIL 12 AND WATER CONSERVATION LEVIES; REPEALING THE SCHOOL ELECTION 13 LAW, THE MAIL BALLOT ELECTION ACT, THE MUNICIPAL ELECTION 14 CODE AND OTHER PROVISIONS OF LAW IN CONFLICT WITH THE LOCAL 15 ELECTION ACT; MAKING CONFORMING AMENDMENTS TO OTHER SECTIONS 16 OF LAW; MAKING AN APPROPRIATION. 17 18 BE IT ENACTED BY THE LEGISLATURE OF THE STATE OF NEW MEXICO: 19 SECTION 1. Section 1-1-19 NMSA 1978 (being Laws 1969, 20 Chapter 240, Section 19, as amended) is amended to read: 21 "1-1-19. ELECTIONS COVERED BY CODE.-- 22 A. The Election Code applies to the following: 23 (1) general elections; 24 (2) primary elections; 25 (3) special elections; HLELC/HB 98 Page 1 1 (4) elections to fill vacancies in the 2 office of United States representative; 3 (5) local elections included in the Local 4 Election Act; and 5 (6) recall elections of county officers, 6 school board members or applicable municipal officers. 7 B. -

Rule 609: Impeachment by Evidence of Conviction of a Crime

RULE 609: IMPEACHMENT BY EVIDENCE OF CONVICTION OF A CRIME Jessica Smith, UNC School of Government (Feb. 2013). Contents I. Generally .........................................................................................................................1 II. For Impeachment Only. ...................................................................................................2 III. Relevant Prior Convictions. .............................................................................................2 A. Rule Only Applies to Certain Classes of Convictions .............................................2 B. Out-of-State Convictions ........................................................................................3 C. Prayer for Judgment Continued (PJC) ...................................................................3 D. No Contest Pleas ...................................................................................................3 E. Charges Absent Convictions ..................................................................................3 F. Effect of Appeal .....................................................................................................3 G. Reversed Convictions ............................................................................................3 H. Pardoned Offenses ................................................................................................3 I. Juvenile Adjudications ...........................................................................................3 J. Age -

Extreme Gerrymandering & the 2018 Midterm

EXTREME GERRYMANDERING & THE 2018 MIDTERM by Laura Royden, Michael Li, and Yurij Rudensky Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law ABOUT THE BRENNAN CENTER FOR JUSTICE The Brennan Center for Justice at NYU School of Law is a nonpartisan law and policy institute that works to reform, revitalize — and when necessary defend — our country’s systems of democracy and justice. At this critical moment, the Brennan Center is dedicated to protecting the rule of law and the values of Constitutional democracy. We focus on voting rights, campaign finance reform, ending mass incarceration, and preserving our liberties while also maintaining our national security. Part think tank, part advocacy group, part cutting-edge communications hub, we start with rigorous research. We craft innovative policies. And we fight for them — in Congress and the states, the courts, and in the court of public opinion. ABOUT THE CENTER’S DEMOCRACY PROGRAM The Brennan Center’s Democracy Program works to repair the broken systems of American democracy. We encourage broad citizen participation by promoting voting and campaign finance reform. We work to secure fair courts and to advance a First Amendment jurisprudence that puts the rights of citizens — not special interests — at the center of our democracy. We collaborate with grassroots groups, advocacy organizations, and government officials to eliminate the obstacles to an effective democracy. ABOUT THE BRENNAN CENTER’S PUBLICATIONS Red cover | Research reports offer in-depth empirical findings. Blue cover | Policy proposals offer innovative, concrete reform solutions. White cover | White papers offer a compelling analysis of a pressing legal or policy issue. -

OEA/Ser.G CP/Doc. 4115/06 8 May 2006 Original: English REPORT OF

OEA/Ser.G CP/doc. 4115/06 8 May 2006 Original: English REPORT OF THE ELECTORAL OBSERVATION MISSION IN BOLIVIA PRESIDENTIAL AND PREFECTS ELECTIONS 2005 This document is being distributed to the permanent missions and will be presented to the Permanent Council of the Organization ORGANIZATION OF AMERICAN STATES REPORT OF THE ELECTORAL OBSERVATION MISSION IN BOLIVIA PRESIDENTIAL AND PREFECTS ELECTIONS 2005 Secretariat for Political Affairs This version is subject to revision and will not be available to the public pending consideration, as the case may be, by the Permanent Council CONTENTS MAIN ABBREVIATIONS vi CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION 1 A. Electoral Process of December 2005 1 B. Legal and Electoral Framework 3 1. Electoral officers 4 2. Political parties 4 3. Citizen groups and indigenous peoples 5 4. Selection of prefects 6 CHAPTER II. MISSION BACKGROUND, OBJECTIVES AND CHARACTERISTICS 7 A. Mission Objectives 7 B. Preliminary Activities 7 C. Establishment of Mission 8 D. Mission Deployment 9 E. Mission Observers in Political Parties 10 F. Reporting Office 10 CHAPTER III. OBSERVATION OF PROCESS 11 A. Electoral Calendar 11 B. Electoral Training 11 1. Training for electoral judges, notaries, and board members11 2. Disseminating and strengthening democratic values 12 C. Computer System 13 D. Monitoring Electoral Spending and Campaigning 14 E. Security 14 CHAPTER IV. PRE-ELECTION STAGE 15 A. Concerns of Political Parties 15 1. National Electoral Court 15 2. Critical points 15 3. Car traffic 16 4. Sealing of ballot boxes 16 5. Media 17 B. Complaints and Reports 17 1. Voter registration rolls 17 2. Disqualification 17 3. -

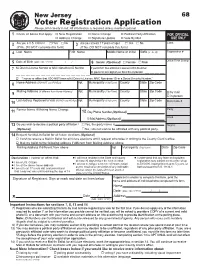

New Jersey 68 Voter Registration Application Please Print Clearly in Ink

New Jersey 68 Voter Registration Application Please print clearly in ink. All information is required unless marked optional. 1 Check all boxes that apply: o New Registration o Name Change o Political Party Affiliation FOR OFFICIAL o Address Change o Signature Update o Vote By Mail USE ONLY 2 Are you a U.S. Citizen? o Yes o No 3 Are you at least 17 years of age? o Yes o No Clerk (If No, DO NOT complete this form) (If No, DO NOT complete this form) 4 Last Name First Name Middle Name or Initial Suffix (Jr., Sr., III) Registration # Office Time Stamp 5 Date of Birth (MM / DD / YYYY) / / 6 Gender (Optional) o Female o Male 7 NJ Driver’s License Number or MVC Non-driver ID Number If you DO NOT have a NJ Driver’s License or MVC Non-Driver ID, provide the last 4 digits of your Social Security Number. __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ o “I swear or affirm that I DO NOT have a NJ Driver’s License, MVC Non-driver ID or a Social Security Number.” Home Address (DO NOT use PO Box) Apt. Municipality (City/Town) County State Zip Code 8 Mailing Address (If different from Home Address) Apt. Municipality (City/Town) County State Zip Code o 9 by mail o in person Last Address Registered to Vote (DO NOT use PO Box) Apt. Municipality (City/Town) County State Zip Code 10 Muni Code # Former Name if Making Name Change Party 11 12 Day Phone Number (Optional) Ward E-Mail Address (Optional) 13 Do you wish to declare a political party affiliation? o Yes, the party name is . -

Roosevelt Neither Hero Nor Villain for the Jews Department Of

Department ofHISTORY College of Arts and Sciences Newsletter 2013-2014 Banner Year for History Faculty Books Contents his past year, American University’s Department of History made history of its Chair’s Letter • Page 2 own. Ten faculty published eight books—three monographs, two co-authored new faculty • Page 3 books, and three co-edited books. Accomplishments • Page 4 THow to explain it? “Not only are our faculty remarkably productive,” says Pamela Bookshelf • Page 5 Nadell, History Department chair, “but the department also has an exciting synergy. Faculty News • Page 6 Richard Breitman and Allan Lichtman’s FDR and the Jews, for example, came out of Student news • Page 7 a friendship and meeting of the minds of colleagues over more than three decades.” American University department of History Turn to page 5 for a brief rundown of the Department of History’s crowded shelf (p) 202-885-2401 (f) 202-885-6166 of recently published books. [email protected] Adapted from web article by Charles Spencer. www.american.edu/cas/history Roosevelt Neither Hero Nor Villain for the Jews n their new book, FDR prisingly limited. “We describe libraries to locate previously Breitman and Lichtman re- and the Jews (Belknap of him as one of the most private unused documents. Ultimately, veal how limited information, Harvard University Press), leaders in American history,” they reconstructed a nuanced bureaucratic languor, and do- IAmerican University Distin- Breitman said. “FDR wrote portrait of FDR’s response mestic political pressures can guished Professors of History no memoirs and precious to Jewish struggles, showing prevent a president from re- few revealing letters, notes, how his attitudes and policies sponding to foreign atrocities or memos.” FDR also did not evolved over time. -

The Truth About Voter Fraud 7 Clerical Or Typographical Errors 7 Bad “Matching” 8 Jumping to Conclusions 9 Voter Mistakes 11 VI

Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law ABOUT THE BRENNAN CENTER FOR JUSTICE The Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law is a non-partisan public policy and law institute that focuses on fundamental issues of democracy and justice. Our work ranges from voting rights to redistricting reform, from access to the courts to presidential power in the fight against terrorism. A sin- gular institution—part think tank, part public interest law firm, part advocacy group—the Brennan Center combines scholarship, legislative and legal advocacy, and communications to win meaningful, measurable change in the public sector. ABOUT THE BRENNAN CENTER’S VOTING RIGHTS AND ELECTIONS PROJECT The Voting Rights and Elections Project works to expand the franchise, to make it as simple as possible for every eligible American to vote, and to ensure that every vote cast is accurately recorded and counted. The Center’s staff provides top-flight legal and policy assistance on a broad range of election administration issues, including voter registration systems, voting technology, voter identification, statewide voter registration list maintenance, and provisional ballots. © 2007. This paper is covered by the Creative Commons “Attribution-No Derivs-NonCommercial” license (see http://creativecommons.org). It may be reproduced in its entirety as long as the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU School of Law is credited, a link to the Center’s web page is provided, and no charge is imposed. The paper may not be reproduced in part or in altered form, or if a fee is charged, without the Center’s permission. -

Voting and Registration in the Election of November 2004

Voting and Registration in the Election of November 2004 Issued March 2006 Population Characteristics P20-556 This report examines the levels of voting Current and registration in the November 2004 ABOUT THIS REPORT Population presidential election, the characteristics Voting and registration rates histori- Reports of citizens who reported that they were cally have been higher in years with registered for or voted in the election, presidential elections than in con- By and the reasons why registered voters gressional election years. For the Kelly Holder did not vote. purposes of this report, the 2004 The data on voting and registration in this data (a presidential election year) report are based on responses to the are compared with previous presi- November 2004 Current Population dential election years (2000, 1996, Survey (CPS) Voting and Registration 1992, etc.). Supplement, which surveys the civilian noninstitutionalized population in the United States.1 The estimates presented 1992, when 68 percent of voting-age in this report may differ from those based citizens voted.3 The overall number of on administrative data or data from exit people who voted in the November 2004 polls. For more information, see the sec- election was 126 million, a record high tion Accuracy of the Estimates. for a presidential election year. Voter turnout increased by 15 million voters VOTING AND REGISTRATION from the election in 2000. During this OF THE VOTING-AGE same 4-year period, the voting-age CITIZEN POPULATION citizen population increased by 11 mil- lion people. Turnout for the November 2004 Election The registration rate of the voting-age In the presidential election of November citizen population, 72 percent, was 2004, the 64 percent of voting-age citi- higher than the 70 percent registered in zens who voted was higher than the the 2000 election. -

The Effect of Gerrymandering on Voter Turnout by Alexa Blaskowsky a THESIS Submitted to Oregon State University Honors College I

The Effect of Gerrymandering on Voter Turnout by Alexa Blaskowsky A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Arts in Political Science (Honors Scholar) Presented May 21, 2021 Commencement June 2021 AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Alexa Blaskowsky for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Arts in Political Science presented on May 21, 2021. Title: The Effect of Gerrymandering on Voter Turnout. Abstract approved:_____________________________________________________ Christopher Stout The relationship between partisan gerrymandering and voter participation has still not been fully understood. Although it is clear that there are many factors that affect voter participation, the effect of gerrymandering on voter participation still has not been studied. In this study, I will be examining if partisan gerrymandering affects voter turnout. I expect that voter participation will decrease the more gerrymandered a state is. I expect this decrease because of the impact gerrymandering has on the winner-loser framework and voter efficacy. To test my hypothesis, I will be studying data from all 50 states from the 2018 congressional election. I found that there is a significant relationship between gerrymandering and voter participation. I also found that a variety of other factors, such as race, play a significant role in decreasing voter participation. Ultimately, my research demonstrates that gerrymandering does affect voter participation to a significant -

Video Evidence a Primer for Prosecutors

Global Justice Information Sharing Initiative Video Evidence A Primer for Prosecutors Even ten years ago, it was rare for a court case to feature video evidence, besides a defendant’s statement. Today, with the increasing use of security cameras by businesses and homeowners, patrol-car dashboard and body-worn cameras by law enforcement, and smartphones and tablet cameras by the general public, it is becoming unusual to see a court case that does not include video evidence. In fact, some estimate that video evidence is involved in about 80 percent of crimes.1 Not surprisingly, this staggering abundance of video brings with it both opportunities and challenges. Two such challenges are dealing with the wide variety of video formats, each with its own proprietary characteristics and requirements, and handling the large file sizes of video evidence. Given these obstacles, the transfer, storage, redaction, disclosure, and preparation of video evidence for evidentiary purposes can stretch the personnel and equipment resources of even the best-funded prosecutor’s office. This primer provides guidance for managing video evidence in the office and suggests steps to take to ensure that this evidence is admissible in court. Global Justice Information Sharing Initiative October 2016 Introduction The opportunities inherent in video evidence cannot be overlooked. It is prosecutors who are charged with presenting evidence to a jury. Today, juries expect video to be presented to them in every case, whether it exists or not.2 As a result, prosecutors must have the resources and technological skill to seamlessly present it in court. Ideally, prosecutors’ offices could form specially trained litigation support units, which manage all video evidence from the beginning of the criminal process through trial preparation and the appellate process.