Advertising in American Comic Books, 1934–2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

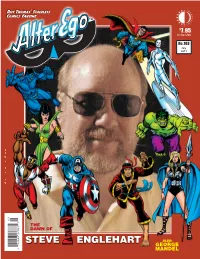

Englehart Steve

AE103Cover FINAL_AE49 Trial Cover.qxd 6/22/11 4:48 PM Page 1 BOOKS FROM TWOMORROWS PUBLISHING Roy Thomas’ Stainless Comics Fanzine $7.95 In the USA No.103 July 2011 STAN LEE UNIVERSE CARMINE INFANTINO SAL BUSCEMA MATT BAKER The ultimate repository of interviews with and PENCILER, PUBLISHER, PROVOCATEUR COMICS’ FAST & FURIOUS ARTIST THE ART OF GLAMOUR mementos about Marvel Comics’ fearless leader! Shines a light on the life and career of the artistic Explores the life and career of one of Marvel Comics’ Biography of the talented master of 1940s “Good (176-page trade paperback) $26.95 and publishing visionary of DC Comics! most recognizable and dependable artists! Girl” art, complete with color story reprints! (192-page hardcover with COLOR) $39.95 (224-page trade paperback) $26.95 (176-page trade paperback with COLOR) $26.95 (192-page hardcover with COLOR) $39.95 QUALITY COMPANION BATCAVE COMPANION EXTRAORDINARY WORKS IMAGE COMICS The first dedicated book about the Golden Age Unlocks the secrets of Batman’s Silver and Bronze OF ALAN MOORE THE ROAD TO INDEPENDENCE publisher that spawned the modern-day “Freedom Ages, following the Dark Knight’s progression from Definitive biography of the Watchmen writer, in a An unprecedented look at the company that sold Fighters”, Plastic Man, and the Blackhawks! 1960s camp to 1970s creature of the night! new, expanded edition! comics in the millions, and their celebrity artists! (256-page trade paperback with COLOR) $31.95 (240-page trade paperback) $26.95 (240-page trade paperback) $29.95 (280-page trade -

BERNARD BAILY Vol

Roy Thomas’ Star-Bedecked $ Comics Fanzine JUST WHEN YOU THOUGHT 8.95 YOU KNEW EVERYTHING THERE In the USA WAS TO KNOW ABOUT THE No.109 May JUSTICE 2012 SOCIETY ofAMERICA!™ 5 0 5 3 6 7 7 2 8 5 Art © DC Comics; Justice Society of America TM & © 2012 DC Comics. Plus: SPECTRE & HOUR-MAN 6 2 8 Co-Creator 1 BERNARD BAILY Vol. 3, No. 109 / April 2012 Editor Roy Thomas Associate Editors Bill Schelly Jim Amash Design & Layout Jon B. Cooke Consulting Editor John Morrow FCA Editor P.C. Hamerlinck AT LAST! Comic Crypt Editor ALL IN Michael T. Gilbert Editorial Honor Roll COLOR FOR $8.95! Jerry G. Bails (founder) Ronn Foss, Biljo White Mike Friedrich Proofreader Rob Smentek Cover Artist Contents George Pérez Writer/Editorial: An All-Star Cast—Of Mind. 2 Cover Colorist Bernard Baily: The Early Years . 3 Tom Ziuko With Special Thanks to: Ken Quattro examines the career of the artist who co-created The Spectre and Hour-Man. “Fairytales Can Come True…” . 17 Rob Allen Roger Hill The Roy Thomas/Michael Bair 1980s JSA retro-series that didn’t quite happen! Heidi Amash Allan Holtz Dave Armstrong Carmine Infantino What If All-Star Comics Had Sported A Variant Line-up? . 25 Amy Baily William B. Jones, Jr. Eugene Baily Jim Kealy Hurricane Heeran imagines different 1940s JSA memberships—and rivals! Jill Baily Kirk Kimball “Will” Power. 33 Regina Baily Paul Levitz Stephen Baily Mark Lewis Pages from that legendary “lost” Golden Age JSA epic—in color for the first time ever! Michael Bair Bob Lubbers “I Absolutely Love What I’m Doing!” . -

Creative Learning in Afterschool Comic Book Clubs

The Robert Bowne Afterschool Matters Foundation OCCASIONAL PAPER SERIES The Art of Democracy/ Democracy as Art: Creative Learning in Afterschool Comic Book Clubs MICHAEL BITZ Civic Connections: Urban Debate and Democracy in Action during Out-of-School Time GEORGIA HALL #7 FALL 2006 The Robert Bowne Foundation Board of Trustees Edmund A. Stanley, Jr., Founder Jennifer Stanley, Chair & President Suzanne C. Carothers, Ph.D., First Vice-President Susan W. Cummiskey, Secretary-Treasurer Dianne Kangisser Jane Quinn Ernest Tollerson Franz von Ziegesar Afterschool Matters Editorial Review Board Charline Barnes Andrews University Mollie Blackburn Ohio State University An-Me Chung C.S. Mott Foundation Pat Edwards Consultant Meredith Honig University of Maryland Anne Lawrence The Robert Bowne Foundation Debe Loxton LA’s BEST Greg McCaslin Center for Arts Education Jeanne Mullgrav New York City Department of Youth & Community Development Gil Noam Program in Afterschool Education and Research, Harvard University Joseph Polman University of Missouri–St. Louis Carter Savage Boys & Girls Clubs of America Katherine Schultz University of Pennsylvania Jason Schwartzman Christian Children’s Fund Joyce Shortt National Institute on Out of School Time (NIOST) Many thanks to Bowne & Company for printing this publication free of charge. RobertThe Bowne Foundation STAFF Lena O. Townsend Executive Director Anne H. Lawrence Program Officer Sara Hill, Ed.D. Research Officer Afterschool Matters Occasional Paper Series No. 7, Fall 2006 Sara Hill, Ed.D. Project Manager -

From Michael Strogoff to Tigers and Traitors ― the Extraordinary Voyages of Jules Verne in Classics Illustrated

Submitted October 3, 2011 Published January 27, 2012 Proposé le 3 octobre 2011 Publié le 27 janvier 2012 From Michael Strogoff to Tigers and Traitors ― The Extraordinary Voyages of Jules Verne in Classics Illustrated William B. Jones, Jr. Abstract From 1941 to 1971, the Classics Illustrated series of comic-book adaptations of works by Shakespeare, Hugo, Dickens, Twain, and others provided a gateway to great literature for millions of young readers. Jules Verne was the most popular author in the Classics catalog, with ten titles in circulation. The first of these to be adapted, Michael Strogoff (June 1946), was the favorite of the Russian-born series founder, Albert L. Kanter. The last to be included, Tigers and Traitors (May 1962), indicated how far among the Extraordinary Voyages the editorial selections could range. This article explores the Classics Illustrated pictorial abridgments of such well-known novels as 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea and Around the World in 80 Days and more esoteric selections such as Off on a Comet and Robur the Conqueror. Attention is given to both the adaptations and the artwork, generously represented, that first drew many readers to Jules Verne. Click on images to view in full size. Résumé De 1941 à 1971, la collection de bandes dessinées des Classics Illustrated (Classiques illustrés) offrant des adaptations d'œuvres de Shakespeare, Hugo, Dickens, Twain, et d'autres a fourni une passerelle vers la grande littérature pour des millions de jeunes lecteurs. Jules Verne a été l'auteur le plus populaire du catalogue des Classics, avec dix titres en circulation. -

Jenette Kahn

Characters TM & © DC Comics. All rights reserved. 0 6 No.57 July 201 2 $ 8 . 9 5 1 82658 27762 8 THE RETRO COMICS EXPERIENCE! JENETTE KAHN president president and publisher with former DC Comics An in-depth interview imprint VERTIGO DC’s The birth of ALSO: Volume 1, Number 57 July 2012 Celebrating The Retro Comics Experience! the Best Comics of the '70s, '80s, '90s, and Beyond! EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael Eury PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich J. Fowlks EISNER AWARDS COVER DESIGNER 2012 NOMINEE Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER Rob Smentek SPECIAL THANKS BEST COMICS-RELATEDJOURNALISM Karen Berger Andy Mangels Alex Boney Nightscream BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury . .2 John Costanza Jerry Ordway INTERVIEW: The Path of Kahn . .3 DC Comics Max Romero Jim Engel Bob Rozakis A step-by-step survey of the storied career of Jenette Kahn, former DC Comics president and pub- Mike Gold Beau Smith lisher, with interviewer Bob Greenberger Grand Comic-Book Roy Thomas Database FLASHBACK: Dollar Comics . .39 Bob Wayne Robert Greenberger This four-quarter, four-color funfest produced many unforgettable late-’70s DCs Brett Weiss Jack C. Harris John Wells PRINCE STREET NEWS: Implosion Happy Hour . .42 Karl Heitmueller Marv Wolfman Ever wonder how the canceled characters reacted to the DC Implosion? Karl Heitmueller bellies Andy Helfer Eddy Zeno Heritage Comics up to the bar with them to find out Auctions AND VERY SPECIAL GREATEST STORIES NEVER TOLD: The Lost DC Kids Line . .45 Alec Holland THANKS TO Sugar & Spike, Thunder and Bludd, and the Oddballs were part of DC’s axed juvie imprint Nicole Hollander Jenette Kahn Paul Levitz BACKSTAGE PASS: A Heroine History of the Wonder Woman Foundation . -

The Trail to LOBO: the First Afrian-American Comic Book Hero

Details: Amazon rank: #1,870,800 Price: $25.75 bound: 132 pages Publisher: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform (March 17, 2017) Language: English ISBN-10: 1544614721 ISBN-13: 978-1544614724 Weight: 9 ounces The Trail to LOBO: the First Afrian-American Comic Book Hero by Tony & Tony Tallarico rating: 5.0 (1 reviews) ->>->>->>DOWNLOAD BOOK The Trail to LOBO: the First Afrian-American Comic Book Hero ->>->>->>ONLINE BOOK The Trail to LOBO: the First Afrian-American Comic Book Hero 1 / 6 2 / 6 3 / 6 4 / 6 . Warner Bros. Has 11 DC Comics Movies . with additional superhero films having . DC currently has a total of eleven comic book film adaptations in .Top 5 Biggest Rip-Off Characters in Comics. They just got the comic book . If everyones going to bitch about who was first then every super hero is a .. Wonder Woman represents not just the first blockbuster helmed by a female superhero, but also the first . The comic book adaptation game is . first black .how is the first black superhero i all comic books? . How is the first black superhero i all comic . Lobo from Dell Comics is the first black .Moved Permanently. The document has moved here. Critical Mention.Watchmen is a twelve-issue comic book limited . of the Black Freighter comic . of the contemporary superhero comic book," is "a domain he .Image of the day: Old school Lobo returns . (duh, hes in every book these days), Black Canary . Fangrrls Wonder Woman Shea Fontana DC Superhero Girls DC .Characters; Comics; Movies; TV; Games; Collectibles; . the first and most influential super hero of all time has inspired us across comic books, .Vintage Lobo #1 Dell Western 1965 1st African American Comic Hero . -

Mason 2015 02Thesis.Pdf (1.969Mb)

‘Page 1, Panel 1…” Creating an Australian Comic Book Series Author Mason, Paul James Published 2015 Thesis Type Thesis (Professional Doctorate) School Queensland College of Art DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/3741 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/367413 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au ‘Page 1, Panel 1…” Creating an Australian Comic Book Series Paul James Mason s2585694 Bachelor of Arts/Fine Art Major Bachelor of Animation with First Class Honours Queensland College of Art Arts, Education and Law Group Griffith University Submitted in fulfillment for the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Visual Arts (DVA) June 2014 Abstract: What methods do writers and illustrators use to visually approach the comic book page in an American Superhero form that can be adapted to create a professional and engaging Australian hero comic? The purpose of this research is to adapt the approaches used by prominent and influential writers and artists in the American superhero/action comic-book field to create an engaging Australian hero comic book. Further, the aim of this thesis is to bridge the gap between the lack of academic writing on the professional practice of the Australian comic industry. In order to achieve this, I explored and learned the methods these prominent and professional US writers and artists use. Compared to the American industry, the creating of comic books in Australia has rarely been documented, particularly in a formal capacity or from a contemporary perspective. The process I used was to navigate through the research and studio practice from the perspective of a solo artist with an interest to learn, and to develop into an artist with a firmer understanding of not only the medium being engaged, but the context in which the medium is being created. -

Matt Baker Baker of Cheesecake / Alberto Becattini / 36 Sidebar: the Geri Shop / Jim Vadeboncoeur Jr

The of Edited by Jim Amash and Art GlamourEric Nolen-Weathington 1 2 4 11 18 22 24 ATT AKER MTheArt of Glamour B edited by Jim Amash and Eric Nolen-Weathington designed by Eric Nolen-Weathington text by Jim Amash • Michael Ambrose Alberto Becattini • Shaun Clancy Dan O’Brien • Ken Quattro • Steven Rowe Jim Vadeboncoeur Jr. and VW Inc. Joanna van Ritbergen TwoMorrows Publishing • Raleigh, North Carolina 33 TABLE OF CONTENTS Part One: Meet Matt Baker BAKER OF CHEESECAKE / Alberto Becattini / 36 Sidebar: The gerI Shop / Jim Vadeboncoeur Jr. / 38 Sidebar: Fox Feature Syndicate / Steven Rowe / 46 Sidebar: St. John Publishing/ Ken Quattro / 49 Sidebar: Elizabeth Waller on It Rhymes with Lust / Shaun Clancy / 52 Sidebar: Charlton Comics / Michael Ambrose / 62 THE MYSTERY OF AcE BAKER / Jim Vadeboncoeur Jr. / 66 Sidebar: Ace Comics / Steven Rowe / 67 THE MATT BAKER CHECKLIST / Alberto Becattini and Jim Vadeboncoeur Jr. / 68 Part Two: Family THE TALENT RUNS DEEP / Jim Amash / 96 FURTHER RUMINATIONS / Joanna van Ritbergen / 118 Part Three: Friends & Colleagues A GREAT FRIENDSHIP / Shaun Clancy / 122 THE BEST MAN FOR THE JOB / Shaun Clancy with Dan O’Brien / 136 …ON MATT BAKER / Jim Amash / 152 Part Four: Comics THE VORTEX OF SCOUNDRELS AND SCANDAL / Phantom Lady, Phantom Lady #14 / 2 THE SODA MINT KILLER / Phantom Lady, Phantom Lady #17 / 12 SKY GIRL / Sky Girl, Jumbo Comics #103 / 24 CANTEEN KATE / Canteen Kate, Anchors Andrews #1 / 31 THE OLD BALL GAME / Canteen Kate, Anchors Andrews #1 / 168 KAYO KIRBY / Kayo Kirby, Fight Comics #54 / 176 TIGER GIRL / Tiger Girl, Fight Comics #52 / 182 35 PART ONE: Meet Matt Baker BAKER OF CHEESECAKE AN APPRECIATION OF MATT BAKER, GOOD GIRL ARTIST SUPREME by Alberto Becattini This is anextended, mended version of the essay which originally appeared in Alter Ego #47 (April 2005). -

Online Collectibles Auction Incl

Complete Auction Service Lot Listing 386 Suncook Valley Hwy. Epsom, NH 03234 (603) 736-9240 Online Collectibles Auction incl. Disney, Britains, Comics 2020-10-12T00:00:00 - 2020-10-18T00:00:00 Lot # Qty Lot # Qty 100 Britains Set #40188 1 140 (3) Sets Britains #7116, #7201, #7249 1 101 7 Scots Gusrd Lead Britains 1 141 Ltd. Ed. Britains Set #00319 Ser. #0624 1 102 1893-1993 Centenary Collection 1 142 Hollow Cast Britains Set #40189 1 103 Britains Ltd. Ed. Set #5195 Ser. #0939 1 143 Britains Set #43056 Grenadier Guards Colour Party 1 104 Britains Ltd. Ed. Set #5295 Ser. #0533 1 144 4 Britains Sets #4311C, 50001C, 49000, 50000C 1 105 Britains Ltd. Ed. Set #5890 Ser. #005953 1 145 Corgi 1902 The Queen's Silver Jubilee 1977 1 106 Britains Ltd. Ed. Set #00105 Ser. #0908/1000 1 146 US Zone Germany Tin Litho Elephant Wind-Up 1 107 Britains Set #8857 1 147 Roaring Bear Wind-Up in Box 1 108 Britains Ltd. Ed. Set #00316 Serial #0226 1 148 Oscar the Seal Key Wind w/Box, TPS 1 109 Britains Set #8898 1 149 Key Wind Tin Litho Spook Bank #90323 w/ Box 1 110 Britains Ltd. Ed. Set #5190 Ser. #003641 1 150 Marx Mechanical Walking Owl w/ Box 1 111 39 Asst. Whitman Uncle Scrooge Comics 1 151 Lot of Mechanical Toys w/ Boxes 1 112 44 Asst. Goldkey Uncle Scrooge Comics 1 152 “Tumbles the Bear” w/ Box #3/3010, Battery Op. 1 113 30 Asst. Uncle Scrooge Comics Mostly Gladstone 1 153 Key-wind Monkey Band (West Germany) 1 114 26 Asst. -

Las Adaptaciones Cinematográficas De Cómics En Estados Unidos (1978-2014)

UNIVERSITAT DE VALÈNCIA Facultat de Filologia, Traducció i Comunicació Departament de Teoria dels Llenguatges i Ciències de la Comunicació Programa de Doctorado en Comunicación Las adaptaciones cinematográficas de cómics en Estados Unidos (1978-2014) TESIS DOCTORAL Presentada por: Celestino Jorge López Catalán Dirigida por: Dr. Jenaro Talens i Dra. Susana Díaz València, 2016 Por Eva. 0. Índice. 1. Introducción ............................................................................................. 1 1.1. Planteamiento y justificación del tema de estudio ....................... 1 1.2. Selección del periodo de análisis ................................................. 9 1.3. Sinergias industriales entre el cine y el cómic ........................... 10 1.4. Los cómics que adaptan películas como género ........................ 17 2. 2. Comparación entre los modos narrativos del cine y el cómic .......... 39 2.1. El guion, el primer paso de la construcción de la historia ....... 41 2.2. La viñeta frente al plano: los componentes básicos esenciales del lenguaje ........................................................................................... 49 2.3. The gutter ................................................................................. 59 2.4. El tiempo .................................................................................. 68 2.5. El sonido ................................................................................... 72 3. Las películas que adaptan cómics entre 1978 y 2014 ........................... 75 -

2News Summer 05 Catalog

$ 8 . 9 5 Dr. Strange and Clea TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc. All Rights Reserved. No.71 Apri l 2014 0 3 1 82658 27762 8 Marvel Premiere Marvel • Premiere Marvel Spotlight • Showcase • 1st Issue Special Showcase • & New more! Talent TRYOUTS, ONE-SHOTS, & ONE-HIT WONDERS! Featuring BRUNNER • COLAN • ENGLEHART • PLOOG • TRIMPE COMICS’ BRONZE AGE AND COMICS’ BRONZE AGE BEYOND! Volume 1, Number 71 April 2014 Celebrating the Best Comics of the '70s, '80s, Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! '90s, and Beyond! EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael Eury PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTIST Arthur Adams (art from the collection of David Mandel) COVER COLORIST ONE-HIT WONDERS: The Bat-Squad . .2 Glenn Whitmore Batman’s small band of British helpers were seen in a single Brave and Bold issue COVER DESIGNER ONE-HIT WONDERS: The Crusader . .4 Michael Kronenberg Hopefully you didn’t grow too attached to the guest hero in Aquaman #56 PROOFREADER Rob Smentek FLASHBACK: Ready for the Marvel Spotlight . .6 Creators galore look back at the series that launched several important concepts SPECIAL THANKS Jack Abramowitz David Kirkpatrick FLASHBACK: Marvel Feature . .14 Arthur Adams Todd Klein Mark Arnold David Anthony Kraft Home to the Defenders, Ant-Man, and Thing team-ups Michael Aushenker Paul Kupperberg Frank Balas Paul Levitz FLASHBACK: Marvel Premiere . .19 Chris Brennaman Steve Lightle A round-up of familiar, freaky, and failed features, with numerous creator anecdotes Norm Breyfogle Dave Lillard Eliot R. Brown David Mandel FLASHBACK: Strange Tales . .33 Cary Burkett Kelvin Mao Jarrod Buttery Marvel Comics The disposable heroes and throwaway characters of Marvel’s weirdest tryout book Nick Cardy David Michelinie Dewey Cassell Allen Milgrom BEYOND CAPES: 221B at DC: Sherlock Holmes at DC Comics . -

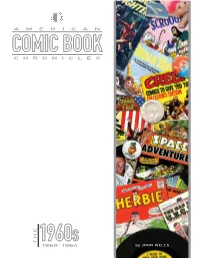

A M E R I C a N C H R O N I C L E S the by JOHN WELLS 1960-1964

AMERICAN CHRONICLES THE 1960-1964 byby JOHN JOHN WELLS Table of Contents Introductory Note about the Chronological Structure of American Comic Book Chroncles ........ 4 Note on Comic Book Sales and Circulation Data......................................................... 5 Introduction & Acknowlegments................................. 6 Chapter One: 1960 Pride and Prejudice ................................................................... 8 Chapter Two: 1961 The Shape of Things to Come ..................................................40 Chapter Three: 1962 Gains and Losses .....................................................................74 Chapter Four: 1963 Triumph and Tragedy ...........................................................114 Chapter Five: 1964 Don’t Get Comfortable ..........................................................160 Works Cited ......................................................................214 Index ..................................................................................220 Notes Introductory Note about the Chronological Structure of American Comic Book Chronicles The monthly date that appears on a comic book head as most Direct Market-exclusive publishers cover doesn’t usually indicate the exact month chose not to put cover dates on their comic books the comic book arrived at the newsstand or at the while some put cover dates that matched the comic book store. Since their inception, American issue’s release date. periodical publishers—including but not limited to comic book publishers—postdated