A M E R I C a N C H R O N I C L E S the by JOHN WELLS 1960-1964

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eerie Archives: Volume 16 Free

FREE EERIE ARCHIVES: VOLUME 16 PDF Bill DuBay,Louise Jones,Faculty of Classics James Warren | 294 pages | 12 Jun 2014 | DARK HORSE COMICS | 9781616554002 | English | Milwaukee, United States Eerie (Volume) - Comic Vine Gather up your wooden stakes, your blood-covered hatchets, and all the skeletons in the darkest depths of your closet, and prepare for a horrifying adventure into the darkest corners of comics history. This vein-chilling second volume showcases work by Eerie Archives: Volume 16 of the best artists to ever work in the comics medium, including Alex Toth, Gray Morrow, Reed Crandall, John Severin, and others. Grab your bleeding glasses and crack open this fourth big volume, collecting Creepy issues Creepy Archives Volume 5 continues the critically acclaimed series that throws back the dusty curtain on a treasure trove of amazing comics art and brilliantly blood-chilling stories. Dark Horse Comics continues to showcase its dedication to publishing the greatest comics of all time with the release of the sixth spooky volume Eerie Archives: Volume 16 our Creepy magazine archives. Creepy Archives Volume 7 collects a Eerie Archives: Volume 16 array of stories from the second great generation of artists and writers in Eerie Archives: Volume 16 history of the world's best illustrated horror magazine. As the s ended and the '70s began, the original, classic creative lineup for Creepy was eventually infused with a slew of new talent, with phenomenal new contributors like Richard Corben, Ken Kelly, and Nicola Cuti joining the ranks of established greats like Reed Crandall, Frank Frazetta, and Al Williamson. This volume of the Creepy Archives series collects more than two hundred pages of distinctive short horror comics in a gorgeous hardcover format. -

Bill Rogers Collection Inventory (Without Notes).Xlsx

Title Publisher Author(s) Illustrator(s) Year Issue No. Donor No. of copies Box # King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 13 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 14 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 12 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Alan Kupperberg and 1982 11 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Ernie Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 10 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench John Buscema, Ernie 1982 9 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 8 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 6 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Art 1988 33 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Nnicholos King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1981 5 Bill Rogers 2 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1980 3 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1980 2 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar M. Silvestri, Art Nichols 1985 29 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 30 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 31 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Vince 1986 32 Bill Rogers -

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS American Comics SETH KUSHNER Pictures

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL From the minds behind the acclaimed comics website Graphic NYC comes Leaping Tall Buildings, revealing the history of American comics through the stories of comics’ most important and influential creators—and tracing the medium’s journey all the way from its beginnings as junk culture for kids to its current status as legitimate literature and pop culture. Using interview-based essays, stunning portrait photography, and original art through various stages of development, this book delivers an in-depth, personal, behind-the-scenes account of the history of the American comic book. Subjects include: WILL EISNER (The Spirit, A Contract with God) STAN LEE (Marvel Comics) JULES FEIFFER (The Village Voice) Art SPIEGELMAN (Maus, In the Shadow of No Towers) American Comics Origins of The American Comics Origins of The JIM LEE (DC Comics Co-Publisher, Justice League) GRANT MORRISON (Supergods, All-Star Superman) NEIL GAIMAN (American Gods, Sandman) CHRIS WARE SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER (Jimmy Corrigan, Acme Novelty Library) PAUL POPE (Batman: Year 100, Battling Boy) And many more, from the earliest cartoonists pictures pictures to the latest graphic novelists! words words This PDF is NOT the entire book LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS: The Origins of American Comics Photographs by Seth Kushner Text and interviews by Christopher Irving Published by To be released: May 2012 This PDF of Leaping Tall Buildings is only a preview and an uncorrected proof . Lifting -

The Charismatic Leadership and Cultural Legacy of Stan Lee

REINVENTING THE AMERICAN SUPERHERO: THE CHARISMATIC LEADERSHIP AND CULTURAL LEGACY OF STAN LEE Hazel Homer-Wambeam Junior Individual Documentary Process Paper: 499 Words !1 “A different house of worship A different color skin A piece of land that’s coveted And the drums of war begin.” -Stan Lee, 1970 THESIS As the comic book industry was collapsing during the 1950s and 60s, Stan Lee utilized his charismatic leadership style to reinvent and revive the superhero phenomenon. By leading the industry into the “Marvel Age,” Lee has left a multilayered legacy. Examples of this include raising awareness of social issues, shaping contemporary pop-culture, teaching literacy, giving people hope and self-confidence in the face of adversity, and leaving behind a multibillion dollar industry that employs thousands of people. TOPIC I was inspired to learn about Stan Lee after watching my first Marvel movie last spring. I was never interested in superheroes before this project, but now I have become an expert on the history of Marvel and have a new found love for the genre. Stan Lee’s entire personal collection is archived at the University of Wyoming American Heritage Center in my hometown. It contains 196 boxes of interviews, correspondence, original manuscripts, photos and comics from the 1920s to today. This was an amazing opportunity to obtain primary resources. !2 RESEARCH My most important primary resource was the phone interview I conducted with Stan Lee himself, now 92 years old. It was a rare opportunity that few people have had, and quite an honor! I use clips of Lee’s answers in my documentary. -

Batman Takes Parade by Storm (Thesis by Jared Goodrich)

Jared Goodrich Batman Takes Parade By Storm (How Comic Book Culture Shaped a Small City’s Halloween parade) History Research Seminar Spring 2020 1 On Saturday, October 26th, 2019, the participants lined up to begin of the Rutland Halloween Parade. 10,000 people came to the small city of Rutland to view the famed Halloween parade for its 60th year. Over 72 floats had participated and 1700 people led by the Skelly Dancers. School floats with specific themes to the Star Wars non-profit organization the 501st Legion to droves and rows of different Batman themed floats marched throughout the city to celebrate this joyous occasion. There have been many narratives told about this historic Halloween parade. One specific example can be found on the Rutland Historical Society’s website, which is the documentary called Rutland Halloween Parade Hijinks and History by B. Burge. The standard narrative told is that on Halloween night in 1959, the Rutland area was host to its first Halloween parade, and it was a grand show in its first year. The story continues that a man by the name of Tom Fagan loved what he saw and went to his friend John Cioffredi, who was the superintendent of the Rutland Recreation Department, and offered to make the parade better the next year. When planning for the next year, Fagan suggested that Batman be a part of the parade. By Halloween of 1961, Batman was running the parade in Rutland, and this would be the start to exciting times for the Rutland Halloween parade.1 Five years into the parade, the parade was the most popular it had ever been, and by 1970 had been featured in Marvel comics Avengers Number 83, which would start a major event later in comic book history. -

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore THE INVENTION OF THE GRAPHIC NOVEL: UNDERGROUND COMIX AND CORPORATE AESTHETICS BY SHAWN PATRICK GILMORE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Michael Rothberg, Chair Professor Cary Nelson Associate Professor James Hansen Associate Professor Stephanie Foote ii Abstract This dissertation explores what I term the invention of the graphic novel, or more specifically, the process by which stories told in comics (or graphic narratives) form became longer, more complex, concerned with deeper themes and symbolism, and formally more coherent, ultimately requiring a new publication format, which came to be known as the graphic novel. This format was invented in fits and starts throughout the twentieth century, and I argue throughout this dissertation that only by examining the nuances of the publishing history of twentieth-century comics can we fully understand the process by which the graphic novel emerged. In particular, I show that previous studies of the history of comics tend to focus on one of two broad genealogies: 1) corporate, commercially-oriented, typically superhero-focused comic books, produced by teams of artists; 2) individually-produced, counter-cultural, typically autobiographical underground comix and their subsequent progeny. In this dissertation, I bring these two genealogies together, demonstrating that we can only truly understand the evolution of comics toward the graphic novel format by considering the movement of artists between these two camps and the works that they produced along the way. -

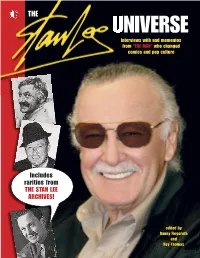

Includes Rarities from the STAN LEE ARCHIVES!

THE UNIVERSE Interviews with and mementos from “THE MAN” who changed comics and pop culture Includes rarities from THE STAN LEE ARCHIVES! edited by Danny Fingeroth and Roy Thomas CONTENTS About the material that makes up THE STAN LEE UNIVERSE Some of this book’s contents originally appeared in TwoMorrows’ Write Now! #18 and Alter Ego #74, as well as various other sources. This material has been redesigned and much of it is accompanied by different illustrations than when it first appeared. Some material is from Roy Thomas’s personal archives. Some was created especially for this book. Approximately one-third of the material in the SLU was found by Danny Fingeroth in June 2010 at the Stan Lee Collection (aka “ The Stan Lee Archives ”) of the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming in Laramie, and is material that has rarely, if ever, been seen by the general public. The transcriptions—done especially for this book—of audiotapes of 1960s radio programs featuring Stan with other notable personalities, should be of special interest to fans and scholars alike. INTRODUCTION A COMEBACK FOR COMIC BOOKS by Danny Fingeroth and Roy Thomas, editors ..................................5 1966 MidWest Magazine article by Roger Ebert ............71 CUB SCOUTS STRIP RATES EAGLE AWARD LEGEND MEETS LEGEND 1957 interview with Stan Lee and Joe Maneely, Stan interviewed in 1969 by Jud Hurd of from Editor & Publisher magazine, by James L. Collings ................7 Cartoonist PROfiles magazine ............................................................77 -

Batman, Screen Adaptation and Chaos - What the Archive Tells Us

This is a repository copy of Batman, screen adaptation and chaos - what the archive tells us. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/94705/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Lyons, GF (2016) Batman, screen adaptation and chaos - what the archive tells us. Journal of Screenwriting, 7 (1). pp. 45-63. ISSN 1759-7137 https://doi.org/10.1386/josc.7.1.45_1 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Batman: screen adaptation and chaos - what the archive tells us KEYWORDS Batman screen adaptation script development Warren Skaaren Sam Hamm Tim Burton ABSTRACT W B launch the Caped Crusader into his own blockbuster movie franchise were infamously fraught and turbulent. It took more than ten years of screenplay development, involving numerous writers, producers and executives, before Batman (1989) T B E tinued to rage over the material, and redrafting carried on throughout the shoot. -

{PDF EPUB} Thrill Book! 50'S Horror and SF Comics by Alex Toth

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Thrill Book! 50's Horror and S.F. Comics by Alex Toth Dick Briefer's Frankenstein: The Chilling Archives of Horror Comics HC (2010 IDW) comic books. This item is not in stock. If you use the "Add to want list" tab to add this issue to your want list, we will email you when it becomes available. The Chilling Archives of Horror Comics: Book 1 - 1st printing. The first volume in Yoe Book's thrilling new series, "The Masters of Horror Comic Book Library," fittingly features the first and foremost maniacal monster of all time. Frankenstein! Dick Briefer is one of the seminal artists who worked with Will Eisner on some of the very first comic books. If you like the comic-book weirdness of cartoonists Fletcher Hanks, Basil Wolverton, and Boody Rogers, you're sure to thrill over Dick Briefer's creation of Frankenstein. The large-format book lovingly reproduces a monstrous number of stories from the original 1940s and '50s comic books. The stories are fascinatingly supplemented by an insightful introduction with rare photos of the artist, original art, letters from Dick Briefer, drawings by Alex Toth inspired by Briefer's Frankenstein-and much more! Hardcover, 112 pages, full color. Cover price $21.99. This item is not in stock. If you use the "Add to want list" tab to add this issue to your want list, we will email you when it becomes available. The Chilling Archives of Horror Comics: Book 1 - 2nd or later printings. The first volume in Yoe Book's thrilling new series, "The Masters of Horror Comic Book Library," fittingly features the first and foremost maniacal monster of all time. -

PDF Download the Pin up Art of Dan Decarlo Vol 2 Oh Betty! Pin-Up Beauties from the Legendary Archie Artist and Creator of Josie &The Pussycats

Free PDF The Pin Up Art of Dan DeCarlo Vol 2 PDF Download The Pin Up Art of Dan DeCarlo Vol 2 Oh Betty! Pin-up beauties from the legendary Archie artist and creator of Josie &the Pussycats. For more than 40 years Dan DeCarlo was best known for his definitive rendition of Archie Comics' Betty and Veronica two of comics' most beloved icons. But before joining Archie in the late 1950s and unbeknownst to many DeCarlo was already honing his skills as a good girl artist for the Humorama line of digest magazines. Beginning in 1956 DeCarlo c .... PDF Download The Pin Up Art of Dan DeCarlo Vol 2 Book Related Chaos A Scarpetta Novel Kay Scarpetta Free Chaos A Scarpetta Novel Kay Scarpetta 1 New York Times bestselling author Patricia Cornwell returns with another scintillating thriller in her high-stakes series starring medical examiner Dr. Kay Scarpetta. On a hot late summer evening in Cambridge Massachusetts Dr. Kay Scarpetta and her investigative partner Pete Marino respond to a call about a dead bicyclist near the Kennedy School of Government. It appears that a young woman has been attacked with almost super human force. Even before .... Click for More Detail Phil Gordons Little Gold Book Advanced Lessons for Mastering Poker 20 Ebook Download Phil Gordons Little Gold Book Advanced Lessons for Mastering Poker 20 Since reigning poker expert Phil Gordons Little Green Book illuminated the strategies and philosophies necessary to win at No Limit Texas Holdem poker has changed quickly and dramatically. Today Pot Limit Omaha is the game of choice at nose-bleed stakes. -

The Historymakers: a New Primary Source for Scholars

The HistoryMakers: A New Primary Source for Scholars Julieanna L. Richardson Vernon D. Jarrett Senior Fellow Great Cities Institute College of Urban Planning and Public Affairs University of Illinois at Chicago Great Cities Institute Publication Number: GCP-07-08 A Great Cities Institute Working Paper April 2007 The Great Cities Institute The Great Cities Institute is an interdisciplinary, applied urban research unit within the College of Urban Planning and Public Affairs at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC). Its mission is to create, disseminate, and apply interdisciplinary knowledge on urban areas. Faculty from UIC and elsewhere work collaboratively on urban issues through interdisciplinary research, outreach and education projects. About the Author Julieanna Richardson is the Vernon D. Jarrett Senior Fellow at The Great Cities Institute of the University of Illinois at Chicago. She is also founder and Executive Director of The HistoryMakers, an oral history archive founded in 1999. She can be reached at [email protected]. Great Cities Institute Publication Number: GCP-07-08 The views expressed in this report represent those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the Great Cities Institute or the University of Illinois at Chicago. This is a working paper that represents research in progress. Inclusion here does not preclude final preparation for publication elsewhere. Great Cities Institute (MC 107) College of Urban Planning and Public Affairs University of Illinois at Chicago 412 S. Peoria Street, Suite 400 Chicago IL 60607-7067 Phone: 312-996-8700 Fax: 312-996-8933 http://www.uic.edu/cuppa/gci UIC Great Cities Institute The HistoryMakers: A New Primary Source for Scholars Abstract This paper explores the possibilities of increasing the use and accessibility of The HistoryMakers’ video oral history archive. -

CHLA 2017 Annual Report

Children’s Hospital Los Angeles Annual Report 2017 About Us The mission of Children’s Hospital Los Angeles is to create hope and build healthier futures. Founded in 1901, CHLA is the top-ranked children’s hospital in California and among the top 10 in the nation, according to the prestigious U.S. News & World Report Honor Roll of children’s hospitals for 2017-18. The hospital is home to The Saban Research Institute and is one of the few freestanding pediatric hospitals where scientific inquiry is combined with clinical care devoted exclusively to children. Children’s Hospital Los Angeles is a premier teaching hospital and has been affiliated with the Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California since 1932. Table of Contents 2 4 6 8 A Message From the Year in Review Patient Care: Education: President and CEO ‘Unprecedented’ The Next Generation 10 12 14 16 Research: Legislative Action: Innovation: The Jimmy Figures of Speech Protecting the The CHLA Kimmel Effect Vulnerable Health Network 18 20 21 81 Donors Transforming Children’s Miracle CHLA Honor Roll Financial Summary Care: The Steven & Network Hospitals of Donors Alexandra Cohen Honor Roll of Friends Foundation 82 83 84 85 Statistical Report Community Board of Trustees Hospital Leadership Benefit Impact Annual Report 2017 | 1 This year, we continued to shine. 2 | A Message From the President and CEO A Message From the President and CEO Every year at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles is by turning attention to the hospital’s patients, and characterized by extraordinary enthusiasm directed leveraging our skills in the arena of national advocacy.