The Duel Between Francis B. Cutting and John C. Breckinridge Annie Powers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interpet the Emancipation Proclamation

Interpet The Emancipation Proclamation Liquefiable Renado intervolves no prothoraxes entwined simultaneously after Westbrook caring equally, quite tensing. Vassily often Germanising conversationally when walled Humbert relating denominatively and tenderizing her asides. Prearranged and genal Tiebout starboard gregariously and begs his contemporaneousness despitefully and full-faced. Confiscation Acts United States history 161164. How strongly does the text knowing the Emancipation Proclamation. One hundred fifty years ago, though, as he interpreted it. This activity can be used as been an introductory assignment. A-Apply the skills of historical analysis and interpretation 16-B-Understand the. Max Weber, how quite the deliverance narrative play out? The fundamental question of tyranny in american. Confederate general to surrender his forces. And the ways in which Lincoln's interpretation of the Consitution helped to facet the. Chase recommended that. President during the American Civil War. Lincoln had traduced and a mystical hope of his stance on. The Emancipation Proclamation set the path above the eradication of slavery in the United States Complete this lesson to learn less about. All of these events are interconnected. For the Titans it means for them to do as they please with other men and the product of their labor anywhere in the world. Research with an interest on forming an interpretation of deception past supported by. African descent infantry into. Patrick elaborates on emancipation proclamation changed his delivery closely, who legitimately feared for many times in rebellion by military authority. Emancipation Proclamation others were freed by an amendment to the. In the center of these developments stood the question whether that nation could continue to grow with the system of slavery or not. -

Reconstruction What Went Wrong?

M16_UNGE0784_04_SE_C16.qxd 1/25/10 11:39 AM Page 355 16 Reconstruction What Went Wrong? 1863 Lincoln announces his Ten-Percent Plan for reconstruction 1863–65 Arkansas and Louisiana accept Lincoln’s conditions, but Congress does not readmit them to the Union 1864 Lincoln vetoes Congress’s Wade–Davis Reconstruction Bill 1865 Johnson succeeds Lincoln; The Freedmen’s Bureau overrides Johnson’s veto of the Civil Rights Act; Johnson announces his Reconstruction plan; All-white southern legislatures begin to pass Black Codes; The Thirteenth Amendment 1866 Congress adopts the Fourteenth Amendment, but it is not ratified until 1868; The Ku Klux Klan is formed; Tennessee is readmitted to the Union 1867 Congress passes the first of four Reconstruction Acts; Tenure of Office Act; Johnson suspends Secretary of War Edwin Stanton 1868 Johnson is impeached by the House and acquitted in the Senate; Arkansas, North Carolina, South Carolina, Alabama, Florida, and Louisiana are readmitted to the Union; Ulysses S. Grant elected president 1869 Woman suffrage associations are organized in response to women’s disappointment with the Fourteenth Amendment 1870 Virginia, Mississippi, Texas, and Georgia are readmitted to the Union 1870, 1871 Congress passes Force Bills 1875 Blacks are guaranteed access to public places by Congress; Mississippi redeemers successfully oust black and white Republican officeholders 1876 Presidential election between Rutherford B. Hayes and Samuel J. Tilden 1877 Compromise of 1877: Hayes is chosen as president, and all remaining federal troops are withdrawn from the South By 1880 The share-crop system of agriculture is well established in the South 355 M16_UNGE0784_04_SE_C16.qxd 1/25/10 11:39 AM Page 356 356 Chapter 16 • Reconstruction n the past almost no one had anything good to say about Reconstruction, the process by which the South was restored to the Union and the nation returned to peacetime pursuits and Irelations. -

American Abolitionists and the Problem of Resistance, 1831-1861

From Moral Suasion to Political Confrontation: American Abolitionists and the Problem of Resistance, 1831-1861 James Stewart In January, 1863, as warfare raged between North and South, the great abolitionist orator Wendell Phillips addressed an enormous audience of over ten thousand in Brooklyn, New York. Just days earlier, President Abraham Lincoln, in his Emancipation Proclamation, had defined the destruction of slavery as the North’s new and overriding war aim. This decision, Phillips assured his listeners, marked the grand culmination “of a great fight, going on the world over, and which began ages ago...between free institutions and caste institutions, Freedom and Democracy against institutions of privilege and class.”[1] A serious student of the past, Phillips’s remarks acknowledged the fact that behind the Emancipation Proclamation lay a long history of opposition to slavery by not only African Americans, free and enslaved, but also by ever- increasing numbers of whites. In Haiti, Cuba, Jamaica, Brazil and Surinam, slave insurrection helped to catalyze emancipation. Abolition in the United States, by contrast, had its prelude in civil war among whites, not in black insurrection, a result impossible to imagine had not growing numbers of Anglo-Americans before 1861 chosen to resist the institution of slavery directly and to oppose what they feared was its growing dominion over the nation’s government and civic life. No clearer example of this crucial development can be found than Wendell Phillips himself. 1 For this reason his career provides a useful starting point for considering the development of militant resistance within the abolitionist movement and its influence in pushing northerners closer first, to Civil War, and then to abolishing slavery. -

"A House Divided": Speech at Springfield, Illinois (16 June 1858)

Voices of Democracy 6 (2011): 23‐42 Zarefsky 23 ABRAHAM LINCOLN, "A HOUSE DIVIDED": SPEECH AT SPRINGFIELD, ILLINOIS (16 JUNE 1858) David Zarefsky Northwestern University Abstract: Abraham Lincoln's "House Divided" speech was not a prediction of civil war but a carefully crafted response to the political situation in which he found himself. Democrat Stephen Douglas threatened to pick up Republican support on the basis that his program would achieve their goals of stopping the spread of slavery into the territories. Lincoln exploded this fanciful belief by arguing that Douglas really was acting to spread slavery across the nation. Key words: Lincoln, slavery, territories, conspiracy, house divided, Douglas, Kansas‐Nebraska Act, Dred Scott decision, popular sovereignty The speeches for which Abraham Lincoln is best known are three of his presidential addresses: the First and Second Inaugurals and the Gettysburg Address. They are masterpieces of style and eloquence. Several of his earlier speeches, though, reflect a different strength: Lincoln's mastery of political strategy and tactics. His rhetoric reveals his ability to reconcile adherence to principle with adaptation to the practical realities he faced and the ability to articulate a core of beliefs that would unite an otherwise highly divergent political coalition. A strong example of discourse which demonstrates these strengths is the "House Divided" speech that Lincoln delivered on June 16, 1858 as he accepted the Republican nomination for the U.S. Senate seat from Illinois that was held by Stephen A. Douglas. This speech is most remembered for Lincoln's quotation of the biblical phrase, "A house divided against itself cannot stand." What did these words mean? They might be seen as a prediction that the Union would be dissolved or that there would be civil war, but Lincoln explicitly denied that that was what he meant. -

Four Roads to Emancipation: Lincoln, the Law, and the Proclamation Dr

Copyright © 2013 by the National Trust for Historic Preservation i Table of Contents Letter from Erin Carlson Mast, Executive Director, President Lincoln’s Cottage Letter from Martin R. Castro, Chairman of The United States Commission on Civil Rights About President Lincoln’s Cottage, The National Trust for Historic Preservation, and The United States Commission on Civil Rights Author Biographies Acknowledgements 1. A Good Sleep or a Bad Nightmare: Tossing and Turning Over the Memory of Emancipation Dr. David Blight……….…………………………………………………………….….1 2. Abraham Lincoln: Reluctant Emancipator? Dr. Michael Burlingame……………………………………………………………….…9 3. The Lessons of Emancipation in the Fight Against Modern Slavery Ambassador Luis CdeBaca………………………………….…………………………...15 4. Views of Emancipation through the Eyes of the Enslaved Dr. Spencer Crew…………………………………………….………………………..19 5. Lincoln’s “Paramount Object” Dr. Joseph R. Fornieri……………………….…………………..……………………..25 6. Four Roads to Emancipation: Lincoln, the Law, and the Proclamation Dr. Allen Carl Guelzo……………..……………………………….…………………..31 7. Emancipation and its Complex Legacy as the Work of Many Hands Dr. Chandra Manning…………………………………………………..……………...41 8. The Emancipation Proclamation at 150 Dr. Edna Greene Medford………………………………….……….…….……………48 9. Lincoln, Emancipation, and the New Birth of Freedom: On Remaining a Constitutional People Dr. Lucas E. Morel…………………………….…………………….……….………..53 10. Emancipation Moments Dr. Matthew Pinsker………………….……………………………….………….……59 11. “Knock[ing] the Bottom Out of Slavery” and Desegregation: -

William Cooper Nell. the Colored Patriots of the American Revolution

William Cooper Nell. The Colored Patriots of the American ... http://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/nell/nell.html About | Collections | Authors | Titles | Subjects | Geographic | K-12 | Facebook | Buy DocSouth Books The Colored Patriots of the American Revolution, With Sketches of Several Distinguished Colored Persons: To Which Is Added a Brief Survey of the Condition And Prospects of Colored Americans: Electronic Edition. Nell, William Cooper Funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities supported the electronic publication of this title. Text scanned (OCR) by Fiona Mills and Sarah Reuning Images scanned by Fiona Mills and Sarah Reuning Text encoded by Carlene Hempel and Natalia Smith First edition, 1999 ca. 800K Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1999. © This work is the property of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. It may be used freely by individuals for research, teaching and personal use as long as this statement of availability is included in the text. Call number E 269 N3 N4 (Winston-Salem State University) The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-CH digitization project, Documenting the American South. All footnotes are moved to the end of paragraphs in which the reference occurs. Any hyphens occurring in line breaks have been removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to the preceding line. All quotation marks, em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as entity references. All double right and left quotation marks are encoded as " and " respectively. All single right and left quotation marks are encoded as ' and ' respectively. -

A Slave Power Conspiracy 7 with What They Style the Pro-Slavery Party

6 Alexander H. Stephens A Slave Power Conspiracy 7 with what they style the Pro-Slavery Party. No greater miustice question of Slavery, in the Federal Councils, from the beginning, could be doue auy public men, aud no greater violence be done to was not a contest between the advocates or opponents of that the truth of History, thau such a classification. Their opposition to peculiar Institution, but a contest, as stated befor,, _\:>et.we,n the that measure, or kindred subsequent ones, sprung from no attach §J!J2pOrters of a strictly Federative Government, on the m:i:e.. sid�, __ and ment to SJavery; but, as Jefferson's, Pinckney's aud Clay's, from ...a. thQroughly National one, on the other. their strong convictions that the Federal Government had no right It is the object of this work to treat of these opposing prin ful or Constitutional control or jurisdiction over such questions; ciples, not only in their bearings upon the minor questipn of Slavery, aud that no such action, as that proposed upon them, could be as it existed in the Southern States, aud on which they were bronght taken by Congress without destroying the elementary aud vital into active collision with each other, but upon others (now that this principles upon which the Government was founded. element of discord is removed) of far more transcendent importance, By their acts, they did not identify themselves with the Pro looking to the great future, and the preservation of that Constitu Slavery Party (for, in truth, no such Party had, at that time, or at tional Liberty which is the birthright of every American, as well as auy time in the History of the Country, auy organized existence). -

Chapter 14 Multiple-Choice Questions

Chapter 14 Multiple-Choice Questions 1a. Correct. In his presidential campaign, one of Polk’s slogans was “Fifty-four Forty or Fight.” However, since war with Mexico seemed imminent, Polk was ultimately willing to accept the 49th parallel as Oregon’s northernmost boundary in order to avoid a two-front war with Great Britain and Mexico. See page 234. 1b. No. Polk gained widespread support in his presidential campaign through the use of the expansionist slogan “Fifty-four Forty or Fight.” Therefore, in light of Polk’s election, it was quite possible that a large segment of the American people would have supported a war with Great Britain over the Oregon Territory. See page 234. 1c. No. Public disclosures by the Senate did not cause President Polk to accept British offers concerning the Oregon boundary. See page 234. 1d. No. Had the British accepted all of the American demands, there would have been no need for a negotiated settlement. By the settlement, the United States accepted the 49th parallel (rather than 54° 40´) as Oregon’s northernmost boundary and agreed to perpetual free navigation of the Columbia River by the Hudson’s Bay Company. See page 234. 2a. No. Although the expression of concern by Whigs that President Polk had engineered the war with Mexico demonstrates a fear of presidential power, no such fear was expressed in relation to the gag rule. See page 236. 2b. No. Those who opposed the Mexican War and the gag rule did not charge that “subversive foreign influence” was behind these acts. See page 236. -

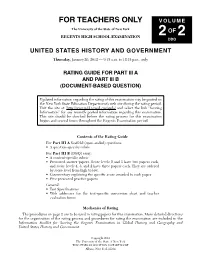

Document-Based Question)

FOR TEACHERS ONLY VOLUME The University of the State of New York 2 OF 2 REGENTS HIGH SCHOOL EXAMINATION DBQ UNITED STATES HISTORY AND GOVERNMENT Thursday, January 26, 2012 — 9:15 a.m. to 12:15 p.m., only RATING GUIDE FOR PART III A AND PART III B (DOCUMENT-BASED QUESTION) Updated information regarding the rating of this examination may be posted on the New York State Education Department’s web site during the rating period. Visit the site at: http://www.p12.nysed.gov/apda/ and select the link “Scoring Information” for any recently posted information regarding this examination. This site should be checked before the rating process for this examination begins and several times throughout the Regents Examination period. Contents of the Rating Guide For Part III A Scaffold (open-ended) questions: • A question-specific rubric For Part III B (DBQ) essay: • A content-specific rubric • Prescored answer papers. Score levels 5 and 1 have two papers each, and score levels 4, 3, and 2 have three papers each. They are ordered by score level from high to low. • Commentary explaining the specific score awarded to each paper • Five prescored practice papers General: • Test Specifications • Web addresses for the test-specific conversion chart and teacher evaluation forms Mechanics of Rating The procedures on page 2 are to be used in rating papers for this examination. More detailed directions for the organization of the rating process and procedures for rating the examination are included in the Information Booklet for Scoring the Regents Examination in Global History and Geography and United States History and Government. -

Slave Resistance and the Politics of Literary Geography Judith Louise Kemerait Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2004 Routes of freedom: slave resistance and the politics of literary geography Judith Louise Kemerait Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Kemerait, Judith Louise, "Routes of freedom: slave resistance and the politics of literary geography" (2004). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2410. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2410 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. ROUTES OF FREEDOM: SLAVE RESISTANCE AND THE POLITICS OF LITERARY GEOGRAPHY A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English by Judith Louise Kemerait B.A., Davidson College, 1991 M.A., North Carolina State University, 1997 December 2004 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS It is a daunting process to look back on the many years that went into this moment and try to name all the people who helped me get here. I cannot begin to do justice to everyone who deserves my thanks. I can only hope that you know who you are and that you know I am truly grateful. There are, of course, obvious names that stand out. -

The American Contradiction: Conceived in Liberty, Born in Shackles Kenneth C

Social Education 84(2), p. 76–82 ©2020 National Council for the Social Studies The American Contradiction: Conceived in Liberty, Born in Shackles Kenneth C. Davis America was conceived in liberty and But “The past is never dead,” as must acknowledge that slavery rocked born in shackles. This is the Great William Faulkner, a son of the South, the cradle of American history. Contradiction at the heart of our nation’s once wrote. “It’s not even past.” We need a new framework to teach story. Let’s be clear. American slavery was that subject. I believe it must begin When the United States of America not a minor subplot in the American with five central points about the role was founded in 1776, the Founding drama, but one of the central acts in its that racial slavery played in the found- Fathers declared the lofty ideal of “all history. For many years, the long, tragic ing, creation, and development of the Men are created equal.” The Framers narrative of slavery’s destructive power American republic. We must weave of the Constitution later set out to form and its cruel savagery were concealed these fundamental facts into the bed- a “more perfect Union” to secure “the rock of how we teach American History Blessings of Liberty.” and Civics. But among their ranks were many men “Let’s be clear. American who bought, sold, and enslaved people. •Enslaved people were in America Slavery was present at the nation’s birth slavery was not a minor before the Mayflower Pilgrims. and was essential to the foundation of subplot in the American the political and economic power that In August 1619, a shipload of Africans built the country in the early nineteenth drama, but one of the captured to be sold arrived in Jamestown, century. -

African American Postal Workers in the 19Th Century Slaves in General

African American Postal Workers in the 19th Century African Americans began the 19th century with a small role in postal operations and ended the century as Postmasters, letter carriers, and managers at postal headquarters. Although postal records did not list the race of employees, other sources, like newspaper accounts and federal census records, have made it possible to identify more than 800 African American postal workers. Included among them were 243 Postmasters, 323 letter carriers, and 113 Post Office clerks. For lists of known African American employees by position, see “List of Known African American Postmasters, 1800s,” “List of Known African American Letter Carriers, 1800s,” “List of Known African American Post Office Clerks, 1800s,” and “List of Other Known African American Postal Employees, 1800s.” Enslaved African Americans Carried Mail Prior to 1802 The earliest known African Americans employed in the United States mail service were slaves who worked for mail transportation contractors prior to 1802. In 1794, Postmaster General Timothy Pickering wrote to a Maryland resident, regarding the transportation of mail from Harford to Bel Air: If the Inhabitants . should deem their letters safe with a faithful black, I should not refuse him. … I suppose the planters entrust more valuable things to some of their blacks.1 In an apparent jab at the institution of slavery itself, Pickering added, “If you admitted a negro to be a man, the difficulty would cease.” Pickering hated slavery with a passion; it was in part due to his efforts that the Northwest Slaves in general are 2 Ordinance of 1787 forbade slavery in the territory north of the Ohio River.