Mannerist Staircases: a Twist in the Tale Valerie Ficklin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

March 27, 2018 RESTORATION of CAPPONI CHAPEL in CHURCH of SANTA FELICITA in FLORENCE, ITALY, COMPLETED THANKS to SUPPORT FROM

Media Contact: For additional information, Libby Mark or Heather Meltzer at Bow Bridge Communications, LLC, New York City; +1 347-460-5566; [email protected]. March 27, 2018 RESTORATION OF CAPPONI CHAPEL IN CHURCH OF SANTA FELICITA IN FLORENCE, ITALY, COMPLETED THANKS TO SUPPORT FROM FRIENDS OF FLORENCE Yearlong project celebrated with the reopening of the Renaissance architectural masterpiece on March 28, 2018: press conference 10:30 am and public event 6:00 pm Washington, DC....Friends of Florence celebrates the completion of a comprehensive restoration of the Capponi Chapel in the 16th-century church Santa Felicita on March 28, 2018. The restoration project, initiated in March 2017, included all the artworks and decorative elements in the Chapel, including Jacopo Pontormo's majestic altarpiece, a large-scale painting depicting the Deposition from the Cross (1525‒28). Enabled by a major donation to Friends of Florence from Kathe and John Dyson of New York, the project was approved by the Soprintendenza Archeologia Belle Arti e Paesaggio di Firenze, Pistoia, e Prato, entrusted to the restorer Daniele Rossi, and monitored by Daniele Rapino, the Pontormo’s Deposition after restoration. Soprintendenza officer responsible for the Santo Spirito neighborhood. The Capponi Chapel was designed by Filippo Brunelleschi for the Barbadori family around 1422. Lodovico di Gino Capponi, a nobleman and wealthy banker, purchased the chapel in 1525 to serve as his family’s mausoleum. In 1526, Capponi commissioned Capponi Chapel, Church of St. Felicita Pontormo to decorate it. Pontormo is considered one of the most before restoration. innovative and original figures of the first half of the 16th century and the Chapel one of his greatest masterpieces. -

The Death Penalty for Drug Crimes in Asia in Violation of International Standards 8

The Death Penalty For Drug Crimes in Asia Report October 2015 / N°665a Cover photo: Chinese police wear masks as they escort two convicted drug pedlars who are suffering from AIDS, for their executions in the eastern city of Hangzhou 25 June 2004 – © AFP TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 4 I- The death penalty for drug-related offences: illegal in principle and in practice 5 Legislation imposing the death penalty for drug crimes: a violation of international legal standards 5 The application of the death penalty for drug crimes in Asia in violation of international standards 8 II. Refuting common justifications for imposing the death penalty for drug crimes 11 III. Country profiles 15 Legend for drug crimes punishable by death in Asia 16 AFGhanisTAN 18 BURMA 20 CHINA 22 INDIA 25 INDONESIA 27 IRAN 30 JAPAN 35 LAOS 37 MALAYSIA 40 PAKISTAN 44 THE PHILIPPINES 47 SINGAPORE 49 SOUTH KOREA 52 SRI LANKA 54 TAIWAN 56 THAILAND 58 VIETNAM 62 Recommendations 64 Legislation on Drug Crimes 67 References 69 Introduction Despite the global move towards abolition over the last decade, whereby more than four out of five countries have either abolished the death penalty or do not practice it, the pro- gress towards abolition or even establishing a moratorium in many countries in Asia has been slow. On the contrary, in The Maldives there was a recent increase in the number of crimes that are punishable by death, and in countries such as Pakistan and Indonesia, who had de-facto moratoriums for several years, executions have resumed. Of particular concern, notably in Asia, is the continued imposition of the death penalty for drug crimes despite this being a clear violation of international human rights stan- dards. -

TREATED with CRUELTY: ABUSES in the NAME of DRUG REHABILITATION Remedies

TREATED WITH CRUELTY ABUSES IN THE NAME OF DRUG REHABILITATION Copyright © 2011 by the Open Society Foundations All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form. For more information, contact: International Harm Reduction Development Program Open Society Foundations www.soros.org/harm-reduction Telephone: 1 212 548 0600 Fax: 1 212 548 4617 Email: [email protected] Cover photo: A heroin user stands in the doorway at the Los Tesoros Escondidos Drug Rehabilita- tion Center in Tijuana, Mexico. Addiction treatment facilities can be brutal and deadly places in Mexico, where better, evidence-based alternatives are rarely available or affordable. (Sandy Huf- faker/ Getty Images) Editing by Roxanne Saucier, Daniel Wolfe, Kathleen Kingsbury, and Paul Silva Design and Layout by: Andiron Studio Open Society Public Health Program The Open Society Public Health Program aims to build societies committed to inclusion, human rights, and justice, in which health-related laws, policies, and practices reflect these values and are based on evidence. The program works to advance the health and human rights of marginalized people by building the capacity of civil society leaders and organiza- tions, and by advocating for greater accountability and transparency in health policy and practice. International Harm Reduction Development Program The International Harm Reduction Development Program (IHRD), part of the Open Society Public Health Program, works to advance the health and human rights of people who use drugs. Through grantmaking, capacity building, and advocacy, IHRD works to reduce HIV, fatal overdose and other drug-related harms; to decrease abuse by police and in places of detention; and to improve the quality of health services. -

The Exhibit at Palazzo Strozzi “Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino

Issue no. 18 - April 2014 CHAMPIONS OF THE “MODERN MANNER” The exhibit at Palazzo Strozzi “Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino. Diverging Paths of Mannerism”, points out the different vocations of the two great artist of the Cinquecento, both trained under Andrea del Sarto. Palazzo Strozzi will be hosting from March 8 to July 20, 2014 a major exhibition entitled Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino. Diverging Paths of Mannerism. The exhibit is devoted to these two painters, the most original and unconventional adepts of the innovative interpretive motif in the season of the Italian Cinquecento named “modern manner” by Vasari. Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino both were born in 1494; Pontormo in Florence and Rosso in nearby Empoli, Tuscany. They trained under Andrea del Sarto. Despite their similarities, the two artists, as the title of the exhibition suggests, exhibited strongly independent artistic approaches. They were “twins”, but hardly identical. An abridgement of the article “I campioni della “maniera moderna” by Antonio Natali - Il Giornale degli Uffizi no. 59, April 2014. Issue no. 18 -April 2014 PONTORMO ACCORDING TO BILL VIOLA The exhibit at Palazzo Strozzi includes American artist Bill Viola’s video installation “The Greeting”, a intensely poetic interpretation of The Visitation by Jacopo Carrucci Through video art and the technique of slow motion, Bill Viola’s richly poetic vision of Pontormo’s painting “Visitazione” brings to the fore the happiness of the two women at their coming together, representing with the same—yet different—poetic sensitivity, the vibrancy achieved by Pontormo, but with a vital, so to speak carnal immediacy of the sense of life, “translated” into the here-and- now of the present. -

Art Historic Rapport

15 SOUTH NETHERLANDISH MASTER Antwerp Mannerism, second half of the 16th century Christ bearing the Cross Oak, carved in high relief H. 43 cm. W. 28 cm. D. 13 cm. PROVENANCE Private collection, Brussels, Belgium his impressive sculpture depicts one of the most popular stations form the Passion TCycle: Christ bearing the Cross. In the centre of the composition, Christ is depicted wearing a long, heavy shroud through which his anatomy is clearly viable. On his head he wears the Crown of Thorns. He carries the Cross over his left shoulder. His upper body and arms are tied with ropes. Christ is flanked by two Roman soldiers wearing Classical styled armour, referring to Ancient Rome. The group is composed moving to the right. The soldier who is leading Christ forward holds a knotted rope in his left hand that runs down from Christ’s shoulders over the soldier’s upper leg and a beating-bat in the hand of his twisted right arm. The soldier wears an outstandingly composed helmet that covers most of his face. Visible are his sharp nose and pointy beard, which lend him sturdy features. The soldier who is standing behind Christ wears a feathered Roman helmet together with an impressive suit of armour, which is embellished with elegant decorations in high relief, featuring a Fig.1. Detail striking grotesque1 on his chest. This soldier holds a bat is his right hand, ready to strike. His muscular body and his powerful, violent pose together with ART HISTORIC SIGNIFICANCE his mocking facial expression, form a remarkable contrast with the solemn and submissive pose of This group is a clear expression of Mannerism: the Christ. -

The Staircase Model” – Labor Control of Temporary Agency Workers in a Swedish Call Center

“The Staircase Model” – Labor Control of Temporary Agency Workers in a Swedish Call Center ❚❚ Gunilla Olofsdotter Senior lecturer in Sociology, Department of Social Sciences, Mid Sweden University, Sweden ABSTRACT The article explores the labor control practices implemented in a call center with extensive con- tracting of temporary agency workers (TAWs). More specifically, the article focuses on how struc- tural and ideological power works in this setting and on the effects of this control for TAWs’ working conditions. Open-ended, semi-structured interviews were conducted with TAWs, regular employees, and a manager in a call center specializing in telecommunication services in Sweden. The results show that ideological power is important in adapting the interests of TAWs to correspond with those of temporary work agencies (TWAs) and their client companies, in this case the call center. The results also show how ideological power is mixed with structural control in terms of technologi- cal control systems and, most importantly, a systematic categorization of workers in a hierarchical structure according to their value to the call center. By systemically categorizing workers in the staircase model, a structural inequality is produced and reproduced in the call center. The motives for working in the call center are often involuntary and are caused by the shortage of work other than a career in support services. As a consequence, feelings of insecurity and an awareness of the precarious nature of their assignment motivate TAWs to enhance their performance and hopefully take a step up on the staircase. This implies new understandings of work where job insecurity has become a normal part of working life. -

He Was More Than a Mannerist - WSJ

9/22/2018 He Was More Than a Mannerist - WSJ DOW JONES, A NEWS CORP COMPANY DJIA 26743.50 0.32% ▲ S&P 500 2929.67 -0.04% ▼ Nasdaq 7986.96 -0.51% ▼ U.S. 10 Yr 032 Yield 3.064% ▼ Crude Oil 70.71 0.55% ▲ This copy is for your personal, noncommercial use only. To order presentationready copies for distribution to your colleagues, clients or customers visit http://www.djreprints.com. https://www.wsj.com/articles/hewasmorethanamannerist1537614000 ART REVIEW He Was More Than a Mannerist Two Jacopo Pontormo masterpieces at the Morgan Library & Museum provide an opportunity to reassess his work. Pontormo’s ‘Visitation’ (c. 152829) PHOTO: CARMIGNANO, PIEVE DI SAN MICHELE ARCANGELO By Cammy Brothers Sept. 22, 2018 700 a.m. ET New York Jacopo Pontormo (1494-1557), one of the most accomplished and intriguing painters Florence ever produced, has been maligned by history on at least two fronts. First, by the great artist biographer Giorgio Vasari, who recognized Pontormo’s gifts but depicted him as a solitary eccentric who imitated the manner of the German painter and printmaker Albrecht Dürer to a fault. And second, by art historians quick to label him as a “Mannerist,” a term that has often carried negative associations, broadly used to mean excessive artifice and often associated with a period of decline. The term isn’t wrong for Pontormo, but it’s a dead end, explaining away Pontormo’s distinctiveness while sidelining him at the same time. It’s not hard to understand how Pontormo got his Pontormo: Miraculous Encounters reputation. -

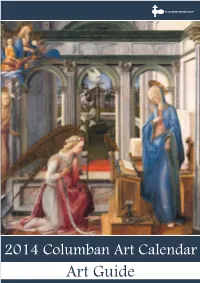

2014 Art Guide

2014 Columban Art Calendar Art Guide Front Cover The Annunciation, Verkuendigung Mariae (detail) Lippi, Fra Filippo (c.1406-1469) In Florence during the late middle ages and Renaissance the story of the Annunciation took on a special meaning. Citizens of this wealthy and pious city dated the beginning of the New Year at the feast day of the Annunciation, March 25th. In this city as elsewhere in Europe, where the cathedral was dedicated to her, the Virgin naturally held a special place in religious life. To emphasize this, Fra Filippo sets the moment of Gabriel’s visit to Mary in stately yet graceful surrounds which recede into unfathomable depths. Unlike Gabriel or Mary, the viewer can detect in the upper left-hand corner the figure of God the Father, who has just released the dove of the Holy Spirit. The dove, a traditional symbol of the third person of the Trinity, descends towards Mary in order to affirm the Trinitarian character of the Incarnation. The angel kneels reverently to deliver astounding news, which Mary accepts with surprising equanimity. Her eyes focus not on her angelic visitor, but rather on the open book before her. Although Luke’s gospel does not describe Mary reading, this detail, derived from apocryphal writings, hints at a profound understanding of Mary’s role in salvation history. Historically Mary almost certainly would not have known how to read. Moreover books like the one we see in Fra Filippo’s painting came into use only in the first centuries CE. Might the artist and the original owner of this painting have greeted the Virgin’s demeanour as a model of complete openness to God’s invitation? The capacity to respond with such inner freedom demanded of Mary and us what Saint Benedict calls “a listening heart”. -

A Literary Journey to Rome

A Literary Journey to Rome A Literary Journey to Rome: From the Sweet Life to the Great Beauty By Christina Höfferer A Literary Journey to Rome: From the Sweet Life to the Great Beauty By Christina Höfferer This book first published 2017 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2017 by Christina Höfferer All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-7328-4 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-7328-4 CONTENTS When the Signora Bachmann Came: A Roman Reportage ......................... 1 Street Art Feminism: Alice Pasquini Spray Paints the Walls of Rome ....... 7 Eataly: The Temple of Slow-food Close to the Pyramide ......................... 11 24 Hours at Ponte Milvio: The Lovers’ Bridge ......................................... 15 The English in Rome: The Keats-Shelley House at the Spanish Steps ...... 21 An Espresso with the Senator: High-level Politics at Caffè Sant'Eustachio ........................................................................................... 25 Ferragosto: When the Romans Leave Rome ............................................. 29 Myths and Legends, Truth and Fiction: How Secret is the Vatican Archive? ................................................................................................... -

Die Baukunst Der Renaissance in Italien Bis Zum Tode Michelangelos

HANDBUCH DER KUNSTWISSENSCHAFT I l.^illich/ P.Zucker 3dul<un(?der Rendipnce td i en HANDBUCHDER KUNSTWISSENSCHAFT BEGRÜNDET VON PROFESSOR Dr. FRITZ BURGER f HERAUSGEGEBEN VON Dr. A. E. BRINCKMANN PROFESSOR AN DER UNIVERSITÄT KÖLN unter Mitwirkung von a. Konservator Dr. E. v. d. Bercken-Müncheii ; Dr. Professor Dr. J. Baum-Ulm D.; i. Pr.; Professor Dr. I. Beth-Berlin; Privatdozent Dr. K. H. Clasen-Könlgsberg Dr. L. Curtius-Heidelberg; Professor Dr. E. Diez-Wien; Privatdozent Dr. W. Drost- Königsberg i. Pr.; Dr. F. Dülberg-Berlin; Professor Dr. K. Escher- Zürich; Hauptkonservator Dr. A. Feulner-München; Professor Dr. P. Frankl-Halle; Dr. O. Grautoff-Berlin; Professor Dr. A. Haupt- Hannover; Professor Dr. E. Hildebrandt -Berlin; Professor Dr. H. Hildebrandt -Stuttgart; Professor Dr. O. Kümmel -Berlin; Professor Dr. A. L. Mayer - München; Dr. N. Pevsner- Dresden; Professor Dr. W. Pinder-München; Professor Dr. H. Schmitz-Berlin; Professor Dr. P. Schubring-Hannover; Professor Dr. Graf Vitzthum-Göttingen; Dr. F. Volbach- Berlin; Professor Dr. M. Wackernagel -Münster; Professor Dr. A. Weese-Bern; Professor Dr. H. Willich - München; Professor Dr. O. Wulff -Berlin; Dr. P. Zucker-Berlin WILDPARK-POTSDAM AKADEMISCHE VERLAGSGESELLSCHAFT ATHENAION M. B. H. ArlA H W DIE BAUKUNST DER RENAISSANCE IN ITALIEN VON DR. ING. HANS WILLICH Professor an der Technischen Hochschule in München UND DR. PAUL ZUCKER II .1' ACADEMIA WILDPARK-POTSDAM AKADEMISCHE VERLAGSGESELLSCHAFT ATHENAION M. B. H. DRUCK DER SPAMERSCHEN BUCHDRUCKEREI IN LEIPZIG Tafel VIII. Der Hof des Palazzo Farnese, erbaut von Antonio da San Gallo nach 1534. Zweiter Teil und Schluß von Dr. Paul Zucker. Kapitel IV. Rom nach der Jahrhundertwende. -

A Transcription and Translation of Ms 469 (F.101R – 129R) of the Vadianische Sammlung of the Kantonsbibliothek of St. Gallen

A SCURRILOUS LETTER TO POPE PAUL III A Transcription and Translation of Ms 469 (f.101r – 129r) of the Vadianische Sammlung of the Kantonsbibliothek of St. Gallen by Paul Hanbridge PRÉCIS A Scurrilous Letter to Pope Paul III. A Transcription and Translation of Ms 469 (f.101r – 129r) of the Vadianische Sammlung of the Kantonsbibliothek of St. Gallen. This study introduces a transcription and English translation of a ‘Letter’ in VS 469. The document is titled: Epistola invectiva Bernhardj Occhinj in qua vita et res gestae Pauli tertij Pont. Max. describuntur . The study notes other versions of the letter located in Florence. It shows that one of these copied the VS469, and that the VS469 is the earliest of the four Mss and was made from an Italian exemplar. An apocryphal document, the ‘Letter’ has been studied briefly by Ochino scholars Karl Benrath and Bendetto Nicolini, though without reference to this particular Ms. The introduction considers alternative contemporary attributions to other authors, including a more proximate determination of the first publication date of the Letter. Mario da Mercato Saraceno, the first official Capuchin ‘chronicler,’ reported a letter Paul III received from Bernardino Ochino in September 1542. Cesare Cantù and the Capuchin historian Melchiorre da Pobladura (Raffaele Turrado Riesco) after him, and quite possibly the first generations of Capuchins, identified the1542 letter with the one in transcribed in these Mss. The author shows this identification to be untenable. The transcription of VS469 is followed by an annotated English translation. Variations between the Mss are footnoted in the translation. © Paul Hanbridge, 2010 A SCURRILOUS LETTER TO POPE PAUL III A Transcription and Translation of Ms 469 (f.101r – 129r) of the Vadianische Sammlung of the Kantonsbibliothek of St. -

Narco-Terrorism: Could the Legislative and Prosecutorial Responses Threaten Our Civil Liberties?

Narco-Terrorism: Could the Legislative and Prosecutorial Responses Threaten Our Civil Liberties? John E. Thomas, Jr.* Table of Contents I. Introduction ................................................................................ 1882 II. Narco-Terrorism ......................................................................... 1885 A. History: The Buildup to Current Legislation ...................... 1885 B. Four Cases Demonstrate the Status Quo .............................. 1888 1. United States v. Corredor-Ibague ................................. 1889 2. United States v. Jiménez-Naranjo ................................. 1890 3. United States v. Mohammed.......................................... 1891 4. United States v. Khan .................................................... 1892 III. Drug-Terror Nexus: Necessary? ................................................ 1893 A. The Case History Supports the Nexus ................................. 1894 B. The Textual History Complicates the Issue ......................... 1895 C. The Statutory History Exposes Congressional Error ............ 1898 IV. Conspiracy: Legitimate? ............................................................ 1904 A. RICO Provides an Analogy ................................................. 1906 B. Public Policy Determines the Proper Result ........................ 1909 V. Hypothetical Situations with a Less Forgiving Prosecutor ......... 1911 A. Terrorist Selling Drugs to Support Terror ............................ 1911 B. Drug Dealer Using Terror to Support Drug