Joint Strategic Needs Assessment Devon Overview 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South West River Basin District Flood Risk Management Plan 2015 to 2021 Habitats Regulation Assessment

South West river basin district Flood Risk Management Plan 2015 to 2021 Habitats Regulation Assessment March 2016 Executive summary The Flood Risk Management Plan (FRMP) for the South West River Basin District (RBD) provides an overview of the range of flood risks from different sources across the 9 catchments of the RBD. The RBD catchments are defined in the River Basin Management Plan (RBMP) and based on the natural configuration of bodies of water (rivers, estuaries, lakes etc.). The FRMP provides a range of objectives and programmes of measures identified to address risks from all flood sources. These are drawn from the many risk management authority plans already in place but also include a range of further strategic developments for the FRMP ‘cycle’ period of 2015 to 2021. The total numbers of measures for the South West RBD FRMP are reported under the following types of flood management action: Types of flood management measures % of RBD measures Prevention – e.g. land use policy, relocating people at risk etc. 21 % Protection – e.g. various forms of asset or property-based protection 54% Preparedness – e.g. awareness raising, forecasting and warnings 21% Recovery and review – e.g. the ‘after care’ from flood events 1% Other – any actions not able to be categorised yet 3% The purpose of the HRA is to report on the likely effects of the FRMP on the network of sites that are internationally designated for nature conservation (European sites), and the HRA has been carried out at the level of detail of the plan. Many measures do not have any expected physical effects on the ground, and have been screened out of consideration including most of the measures under the categories of Prevention, Preparedness, Recovery and Review. -

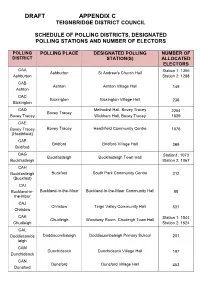

DRAFT Schedule of Polling Places and Designated Polling Stations

DRAFT APPENDIX C TEIGNBRIDGE DISTRICT COUNCIL SCHEDULE OF POLLING DISTRICTS, DESIGNATED POLLING STATIONS AND NUMBER OF ELECTORS POLLING POLLING PLACE DESIGNATED POLLING NUMBER OF DISTRICT STATION(S) ALLOCATED ELECTORS CAA Station 1: 1366 Ashburton St Andrew’s Church Hall Ashburton Station 2: 1288 CAB Ashton Ashton Village Hall 149 Ashton CAC Bickington Bickington Village Hall 236 Bickington CAD Methodist Hall, Bovey Tracey 2254 Bovey Tracey Bovey Tracey Wickham Hall, Bovey Tracey 1839 CAE Bovey Tracey Bovey Tracey Heathfield Community Centre 1076 (Heathfield) CAF Bridford Bridford Village Hall 369 Bridford CAG Station1: 1073 Buckfastleigh Buckfastleigh Town Hall Buckfastleigh Station 2: 1067 CAH Buckfastleigh Buckfast South Park Community Centre 312 (Buckfast) CAI Buckland-in- Buckland-in-the-Moor Buckland-in-the-Moor Community Hall 88 the-Moor CAJ Christow Teign Valley Community Hall 631 Christow CAK Station 1: 1544 Chudleigh Woodway Room, Chudeigh Town Hall Chudleigh Station 2: 1524 CAL Doddiscombs Doddiscombsleigh Doddiscombsleigh Primary School 201 leigh CAM Dunchideock Dunchideock Village Hall 197 Dunchideock CAN Dunsford Dunsford Village Hall 453 Dunsford DRAFT APPENDIX C CAO Station 1: 1397 Exminster Victory Hall, Exminster Exminster Station 2: 1439 CAP Hennock Hennock Hennock Village Hall 334 (Village) CAQ Hennock Chudleigh Knighton Chudleigh Knighton Village Hall 884 (Chudleigh Knighton) CAR Holcombe Holcombe Burnell Longdown Village Hall 405 Burnell CAS Ide Ide Memorial Hall 388 Ide CAT Ilsington Ilsington Village Hall 475 Ilsington -

Old Mill House Freehold Old Mill House, Combeinteignhead, Devon, TQ12 4RE a Characterful Detached Family Home Nestled in a Semi-Rural Location

Old Mill House Freehold Old Mill House, Combeinteignhead, Devon, TQ12 4RE A characterful detached family home nestled in a semi-rural location. • Historic Former Mill House • Sympathetic Refurbishment • 4 Bedrooms • Landscaped Gardens • Lounge With Log Burner • Garage & Off Road Parking • Dining Room With Fireplace • Semi-Rural Location • Double Glazing & Mainly Underfloor Heating • Viewing Highly Recommended This historic Mill House has been beautifully refurbished by tucked away and convenient, two qualities that are not often the current owners. It offers balanced accommodation in a available together. This is a not to be missed opportunity to rural setting along with easy access to Newton Abbot, Shaldon acquire a home of distinction. and Torquay. It is located part way between the picturesque and sought after villages of Combe in Teignhead and Stoke ACCOMMODATION in Teignhead, each having its own character and amenities Ground Floor including; pubs/restaurants, a well-regarded primary school, Entrance Porch historic churches, active village halls and a village shop. A further Hallway extensive range of facilities and mainline railway stations can Lounge 14' 1" (4.3m) x 12' 6" (3.8m) be found in Newton Abbot or Torquay which are both around 4 Dining Room 14' 9" (4.5m) x 12' 6" (3.8m) miles distant, both towns have good road links to more distant Kitchen 26' 3" (8m) x 6' 7" (2m) locations including Exeter Airport 25 miles away which offers Study 5' 11" (1.8m) x 4' 7" (1.4m) regular flights to London and Edinburgh along with many Garage 14' 9" (4.5m) x 7' 10" (2.4m) overseas destinations. -

International Passenger Survey, 2008

UK Data Archive Study Number 5993 - International Passenger Survey, 2008 Airline code Airline name Code 2L 2L Helvetic Airways 26099 2M 2M Moldavian Airlines (Dump 31999 2R 2R Star Airlines (Dump) 07099 2T 2T Canada 3000 Airln (Dump) 80099 3D 3D Denim Air (Dump) 11099 3M 3M Gulf Stream Interntnal (Dump) 81099 3W 3W Euro Manx 01699 4L 4L Air Astana 31599 4P 4P Polonia 30699 4R 4R Hamburg International 08099 4U 4U German Wings 08011 5A 5A Air Atlanta 01099 5D 5D Vbird 11099 5E 5E Base Airlines (Dump) 11099 5G 5G Skyservice Airlines 80099 5P 5P SkyEurope Airlines Hungary 30599 5Q 5Q EuroCeltic Airways 01099 5R 5R Karthago Airlines 35499 5W 5W Astraeus 01062 6B 6B Britannia Airways 20099 6H 6H Israir (Airlines and Tourism ltd) 57099 6N 6N Trans Travel Airlines (Dump) 11099 6Q 6Q Slovak Airlines 30499 6U 6U Air Ukraine 32201 7B 7B Kras Air (Dump) 30999 7G 7G MK Airlines (Dump) 01099 7L 7L Sun d'Or International 57099 7W 7W Air Sask 80099 7Y 7Y EAE European Air Express 08099 8A 8A Atlas Blue 35299 8F 8F Fischer Air 30399 8L 8L Newair (Dump) 12099 8Q 8Q Onur Air (Dump) 16099 8U 8U Afriqiyah Airways 35199 9C 9C Gill Aviation (Dump) 01099 9G 9G Galaxy Airways (Dump) 22099 9L 9L Colgan Air (Dump) 81099 9P 9P Pelangi Air (Dump) 60599 9R 9R Phuket Airlines 66499 9S 9S Blue Panorama Airlines 10099 9U 9U Air Moldova (Dump) 31999 9W 9W Jet Airways (Dump) 61099 9Y 9Y Air Kazakstan (Dump) 31599 A3 A3 Aegean Airlines 22099 A7 A7 Air Plus Comet 25099 AA AA American Airlines 81028 AAA1 AAA Ansett Air Australia (Dump) 50099 AAA2 AAA Ansett New Zealand (Dump) -

February 2021 Minutes

Haccombe-with-Combe Parish Council www.haccombewithcombe.co.uk Minutes of the Parish Council Meeting held on Zoom on 3 February 2021 at 7.30pm Present: Councillors Boarer (Chairman), Bunce, Hosking, Humble, Hussey and Pattinson Also present: County Councillor Dewhirst, District Cllr Haines and eight members of the public Clerk: Suzanna Hughes 030221.01 APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE • Cllr Evans • County Cllr Hook • Elizabeth Deane (Hearn Field Committee Chairman) 030221.02 POLICE REPORT There were no crimes recorded in Combeinteignhead during the period 1 January – 31 January 2021. This month, the police are looking to target local poaching issues/rural wildlife crime in and around the area. If anyone has any information or sees anything suspicious please report it to the police. Community Speed Watch is currently on hold due to the current lockdown. This will resume when restrictions ease. PACT meetings will also hopefully resume soon. Cllr Hussey advised that, through the Councillor Advocate Scheme, he had received details about how to report suspected Covid-19 breaches to the police. Details had also been circulated about how to contact the police in a non-emergency. Cllr Hussey advised that he had posted this information on the noticeboards and also agreed to send it to Cllr Evans for inclusion on the parish website. 030221.03 OPEN FORUM There were no items raised. 030221.04 DISTRICT AND COUNTY COUNCILLORS’ REPORTS District Cllr Haines reported that the proposed council tax rise which is now out for consultation and decision later this month is £5 per annum. He reported that he had attended a meeting of the Housing and Employment Land Availability Assessment as part of the Local Plan process. -

CHURCH of ENGLAND DEVON PRAYERS CHURCH of ENGLAND Sun 21St – Sat 27Th January This Week We Pray for All Those Who Are Cold Or Hungry

CHURCH OF ENGLAND DEVON PRAYERS CHURCH OF ENGLAND Sun 21st – Sat 27th January This week we pray for all those who are cold or hungry. This week why not chat to a Big Issue vendor DEVON and support their work to improve their life through the social enterprise. 21. For the Seaton and Beer Coastal Mission Loxhore, Kentisbury, East Down with Arlington, At the start of this New Year hold in prayer Community, their priest Jeremy Trew and for all Challacombe and Bratton Fleming. rayers all those who you know have had a difficult who live and worship in Seaton and Beer. 26. In our link with Melanesia we hold in our P last year and ask God to be especially close to 22. Pray for our bishops Robert, Nick and Sarah prayers the Anglican Province of Melanesia them this coming year. and for all those other South West bishops which was inaugurated in 1975 on this day. meeting together in Exeter today. Please pray for all the staff, ordained and 23. Pray for all our hospital chaplains and in laity who work for the Anglican Church of Mon1st – Sat 6th January particular for the work of Andy Barton, Melanesia. We also give thanks for those Palliative Care and Oncology Chaplain, based in who work at the church’s printing press and the department of Pastoral and Spiritual Care bookshop, and all those who work in the 1. On New Year’s Day we pray: Shine your light rapid growth in construction/population and at Plymouth Hospital. church’s shipyard and on the floating church the Southern Cross ship. -

Frog Cottage, Combeinteignhead, Newton Abbot, Devon, TQ12 4RA

Frog Cottage, Combeinteignhead, Newton Abbot, Devon, TQ12 4RA A charming thatched cottage in a sought after village Shaldon 2 miles Teignmouth 3 miles Exeter 19 miles • Superb kitchen/dining room with AGA • Characterful sitting room • 3 first floor bedrooms • Family bathroom and shower room • Pretty cottage gardens • Convenient location • Available end of £1,350 Per calendar month EPC Band TBC 01803 866130 | [email protected] Cornwall | Devon | Somerset | Dorset | London stags.co.uk Combeinteignhead, Newton Abbot, Devon, TQ12 4RA SITUATION To the rear of the property, there are pretty cottage-style Frog Cottage is well-positioned within the heart of the gardens and courtyards with a raised paved terrace, popular Teign Estuary village of Combeinteignhead with providing a perfect spot for alfresco dining and outdoor the position having a pleasant open south-facing aspect entertaining. across the pretty valley. The village has a good sense of community with a village hall, the popular Wild Goose The pretty landscaped garden is principally laid to two public house and the Coombe Cellars, a public house terraces of lawn with borders and raised areas of bedding and eatery in a superb waterside setting where there is which are stocked with a beautiful array of flowering also a dingy sailing club, as well as being a popular spot plants including a mature rose bed. for windsurfing and water skiing etc. The high beech hedge runs along the rear of the plot The slightly larger village of Stokeinteignhead lies around which provides a good degree of privacy and seclusion. a mile away and has a well-regarding primary school a community shop and a farm shop nearby. -

Devon Archives & Local Studies

Devon Archives & Local Studies Devon Family History & Local History Books on CD The following CDs are for sale in our reception bookshop and CDs other than those published by Bernard Welchman are also available to researchers in Devon Heritage Centre searchroom. These items can also be ordered by email, [email protected]. Please ask for an estimate of the cost of postage and packing before sending your payment. We accept payments by cheque, made payable to ‘South West Heritage Trust Trading Ltd’. We can also accept payments by the following credit or debit cards: Visa, Visa Debit, Visa Electron, Access, Mastercard, Maestro, Solo. Regrettably, we cannot accept American Express or Diners Club. If paying over the phone, please call 01392 888700. The following CDs are produced by Bernard Welchman. The Borders of the Tamar and Tavy (Mrs Bray) This book is in the form of letters that were written by Mrs Bray to Robert Southey. These give detailed descriptions of such diverse subjects as: The Damnonii and their Castle, Rock Basins, Mists of Dartmoor, The Warren, Brigadier Herring, Monasteries, Tomb of Orgar, Hermitage of St. John, Edward Smith, The Great Rebellion, The Atkynses, And many, many more. £7.50 Devon Lay Subsidy Rolls 1543 – 1545 (Edited by T L Stoate) This is a CD of the surviving Subsidy Rolls of Devon, but does not include Exeter, because its 1544 roll has been transcribed by Mrs Rowe in the "Tudor Exeter" (Devon and Cornwall Record Society. Volume 22, 1977). There are many thousands of people listed usually giving their parish and the value that the person is assessed at. -

Inter-Parish, Transhumant and Transient Migrants in Devon: 1600 – 1800 Marion Hardy Devon History Society & British Association for Local History

1 Inter-parish, transhumant and transient migrants in Devon: 1600 – 1800 Marion Hardy Devon History Society & British Association for Local History John Milford was born in Chulmleigh in Devon, marked ‘C’ in Figure 1, about 1725/6, the base child of Sarah Milford. He became a parish apprentice until he was 17, when his master had no further employment for him. He found residential employment at a weekly rate of 6d until he was 19 when he went to Newton Bushell (Newton Abbot) for 6 months before gaining a contract to go to Newfoundland for ‘about a year’, so probably for two summers and a winter. He returned to Bristol, worked by the week for some time and then spent a year as a labourer on the Bridgewater and Wells turnpike road. John then returned to work in Rose Ash in Devon. When he was turned away he became a day labourer and married about 5 years later. In 1766, he was examined by the overseers of Chulmleigh.1 John had moved between parishes, he had undertaken transatlantic transhumance in the fishing industry and then been a transient migrant through Somerset to arrive back in Chulmleigh the overseers’ settlement examination revealed his story. Information from settlement certificates and settlement examinations is available after 1662, but other information is available from the records of churchwardens and Devon county quarter sessions’ record books and bundles of examinations.2 (The relative importance of these records changed in 1700.3) Inter-parish migration was probably the most common form of population movement, although the evidence before 1662 is limited to that from churchwardens’ accounts and quarter sessions’ records. -

886 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

886 bus time schedule & line map 886 Teignmouth - Newton Abbot View In Website Mode The 886 bus line (Teignmouth - Newton Abbot) has 3 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Newton Abbot: 9:20 AM - 11:50 AM (2) Shaldon: 12:45 PM (3) Teignmouth: 10:05 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 886 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 886 bus arriving. Direction: Newton Abbot 886 bus Time Schedule 22 stops Newton Abbot Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday Not Operational Seaview Diner, Teignmouth Esplanade, Teignmouth Tuesday Not Operational Post O∆ce, Teignmouth Wednesday 9:20 AM - 11:50 AM Den Road, Teignmouth Thursday Not Operational Orchard Gardens, Teignmouth Friday 9:20 AM - 11:50 AM Orchard Gardens, Teignmouth Saturday Not Operational Bitton Park Flats, Teignmouth Gloucester Road, Teignmouth Bitton Park, Teignmouth Chelsea Place, Teignmouth 886 bus Info Direction: Newton Abbot Tesco Express, Teignmouth Stops: 22 106 Bitton Park Road, Teignmouth Trip Duration: 40 min Line Summary: Seaview Diner, Teignmouth, Post Shaldon Bridge, Teignmouth O∆ce, Teignmouth, Orchard Gardens, Teignmouth, Bishopsteignton Road, Teignmouth Bitton Park Flats, Teignmouth, Bitton Park, Teignmouth, Tesco Express, Teignmouth, Shaldon Bridge Road, Shaldon Bridge, Teignmouth, Bridge Road, Shaldon, Topcliffe Bridge Road, Teignmouth Road, Shaldon, Devon Valley Holiday Village, Combeinteignhead, Old Post O∆ce, Topcliffe Road, Shaldon Combeinteignhead, Church House Inn, Clifford Close, Teignmouth Stokeinteignhead, -

24 Archbrook Meadow and Land at Arch Brook, Combeinteignhead

LOT Archbrook Meadow and Land at Arch Brook, Combeinteignhead, 24 Newton Abbot, Devon TQ12 4RS *GUIDE PRICE £300,000–£350,000 A unique opportunity to acquire 5.18ha/12.79 acres of mixed pasture, woodland and ponds, along with stabling, outbuildings and three bedroom caravan in this extremely sought after waterfront location. LOCATION EPC Teignharvey is situated on the southern banks Energy Efficiency Rating – Exempt of the River Teign between Shaldon and Combeinteignhead, in an area surrounded AUCTION VALUER by rolling countryside and the ever changing Wendy Alexander scene of the River Teign. Shaldon and Teignmouth have an excellent range of VIEWING recreational facilities for a variety of water Strictly by appointment with Countrywide sports and coastal walks as well as local shops Property Auctions 0151 734 7509 (Monday and educational facilities. to Friday); Fulfords Teignmouth 01626 770077 (Weekends). ALL VIEWINGS MUST BE DESCRIPTION ACCOMPANIED. A unique opportunity to acquire circa 5.18 hectares/12.79 acres of mixed pasture, NOTES woodland and ponds in the highly sought after Measurements have been made using waterside location of Teignharvey. The property the Promap mapping facility, interested has the benefit of 10 stables, some with parties must make and rely upon their own storage over, a useful range of outbuildings measurements. The Promap shown is for and tack rooms, a former piggery, fields and approximate identification purposes only and is turnout paddocks, two ponds, a 32’ three not to scale. Crown Copyright Reserved. bedroom caravan and formal gardens with specimen trees and shrubs. All of the fields have the benefit of either a mains water supply or a natural water supply and are ring fenced, with electricity to the buildings currently being supplied via a generator and lpg tank serving the caravan. -

Middle Rocombe Farm 8PP .Qxp Stags 06/03/2017 16:38 Page 1

Middle Rocombe Farm 8PP .qxp_Stags 06/03/2017 16:38 Page 1 Middle Rocombe Farm Stokeinteignhead, South Devon Middle Rocombe Farm 8PP .qxp_Stags 06/03/2017 16:38 Page 2 Middle Rocombe Farm 8PP .qxp_Stags 06/03/2017 16:38 Page 3 Middle Rocombe Farm Stokeinteignhead, Newton Abbot, Devon TQ12 4QL Combeinteignhead/Stokeinteignhead 1 mile • South Devon Highway/Newton Abbot 3 miles • Exeter 19 miles An exciting opportunity to purchase the whole or a number of lots of this unique lifestyle property, combining traditional and contemporary architecture in a beautiful rural location yet close to excellent amenities and travel connections The vendors wish to sell for residential occupation only, therefore holiday let purchases will not be allowed. • Traditional farmhouse with 5 bedrooms and a large garden • Planning permission granted for conversion of a studio into a residential dwelling with an additional artist studio and offices of some 230sqm and garden • Planning granted for conversion of two traditional barns into two 3-bed full residential dwellings • Communal courtyard for the use of all the dwellings • Allocated parking • There will be an option to buy Lot 2: a 1-2 bed cottage which is currently occupied with tenants on an AST for a period of 2 years • For sale as a whole or in 5 Lots Stags The Modern House Ltd The Granary The London Office 63 Halliford Street Coronation Road, Totnes 40 St James’s Place London Devon TQ9 5GN London N1 3HF Tel: 01803 865454 SW1A 1NS Tel: 020 3795 5920 Email: [email protected] Tel: 020 7839 0888 Email: [email protected] stags.co.uk Middle Rocombe Farm 8PP .qxp_Stags 06/03/2017 16:38 Page 4 Situation Middle Rocombe Farm occupies an outstanding position in a most beautiful and peaceful valley, close to the stunning South Devon coastline and South West Coastal path.