Separate and Unequal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anti Racism Discussion Guide

ANTI-RACISM DISCUSSION GUIDE Nationwide uprisings against police brutality and movements like Black Lives Matter have brought systemic racism to the forefront—making it imperative for district and school leaders to cultivate anti-racist school systems. Historically, district leaders have focused on multicultural literacy and implicit bias training, but the national conversation has catalyzed a focus on anti-racism. District leaders across the country are asking how they as individuals can (a) examine their own beliefs and actions and (b) foster an environment in which they can push conversations about race, racism, and other equity issues. Although conversations about race pull individuals out of their comfort zones and, at times, lead to conflict and tension between participants, it is important to lead productive discussions about equity issues in your districts and schools. We created this discussion guide to help leaders effectively navigate these topics by establishing goals for equity discussions, brainstorming questions for holding constructive conversations, and identifying actions to take as a result of the perspectives and information shared. I identify how I may unknowingly benefit from racism I promote & advocate DEFINE WHAT YOU for policies & leaders I recognize racism that are anti-racist is a present & current problem I seek out questions HOPE TO EXAMINE that make me I sit with my uncomfortable. discomfort I deny racism is a problem There are several frameworks available in surrounding I speak out I avoid hard I understand my when I see anti-racism research; therefore, it is critical for districts questions own privilege in racism in action to define what they hope to examine. -

The Black Atlantic As a Counterculture of Modernity

1 The Black Atlantic as a Counterculture of Modernity We who are bomeless,-Among Europeans today there is no lack of those who are entitled to call themselves homeless in a distinctive and honourable sense .. We children of the future, how could we be at bome in this today~ We feel disfavour for all ideals that might lead one to feel at home even in this fragile, broken time of transition; as fur "'realities," we do not believe that they will last. The ice that still supports people today has become very thin; the wind that brings the thaw is blowing; we ourselves who are homeless constitute a force that breaks open ice and other aU too thin "realities." NietssdIe On the notion of modernity. It is a vexed question. Is not every era "'modern" in relation to the preceding one? It seems that at least one of the components of "our" modernity is the spread of the awareness we have ofit. The awareness of our awareness (the double, the second degree) is our source of strength and our torment. BIW_nl GlissRnt STRIVING TO BE both European and black requires some specific forms of double consciousness. By saying this I do not mean to suggest that taking on either or both of these unfinished identities necessarily ex hausts the subjective resources of any parti.cuIar individual. However, where racist, nationalist, or ethnically absolutist discourses orchestrate po litical relationships so that these identities appear to be mutually exclusive, occupying the space: between them or trying to demonstrate their continu ity has been viewed as a provocative and even oppositional act of political insubordination. -

Exploring Race and Privilege

Exploring Race and Privilege Exploring Race and Privilege presents materials on culturally responsive supervision from the second of a three‐part series designed for supervisors in teacher education. This series was developed in partnership with Dr. Tanisha Brandon‐ Felder, a consultant in professional development on equity pedagogy. This document contains handouts, planning tools, readings, and other materials to provide field supervisors with a scaffolded experience to improve their ability for culturally responsive supervision. The following materials build on the trust and community developed through the first set of activities The Power of Identity. Exploration of race and concepts such as white privilege will necessitate shared understanding of language and norms for conversation. 1. Understanding the Language of Race and Diversity 2. Ground Rules for Conversation 3. Color Line Instructions 4. Color Line Handout 5. White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack by Peggy McIntosh Understanding the Language of Race and Diversity Terms we all need to know: PREJUDICE Pre‐judgment, bias DISCRIMINATION Prejudice + action OPPRESSION Discrimination + systemic power. (Systemic advantage based on a particular social identity.) Racism = oppression based race‐ the socially constructed meaning attached to a variety of physical attributes including but not limited to skin and eye color, hair texture, and bone structure of people in the US and elsewhere. racism‐ the conscious or unconscious, intentional or unintentional, enactment of racial power, grounded in racial prejudice, by an individual or group against another individual or group perceived to have lower racial status. Types of racism: Internalized Racism Lies within individuals. Refers to private beliefs and biases about race and racism. -

A History of Race Relations Social Science

A History of Race Relations Social Science Vernon J. Williams, Jr. Purdue University This essay argues that the inclusion of white women, African Americans, Asian Americans, and American Indians into historiography is a fairly recent development; and that the aforementioned development, which did not begin until the 1960s, has resulted in rigorous investigation into the racial thought of Franz Uri Boas, Robert Ezra Park, and Gunnar Myrdal and a hot debate in reference to their significance and influence on today's social sciences. Furthermore, the integration of Af rican American history into the historiography of race relations social science has given impetus to the move ment towards making American intellectual history more inclusive. The purposes of this essay are twofold: first, it seeks to articulate the current scholarly debates centered around the purpose of the writings of Franz Uri Boas, Robert Ezra Park, and Gunnar Myrdal and their contributions to an understanding of Black-white relations in the United States; and second, it examines and analyzes the integration of African American history into the subfield of race relations social science. In so doing, I hope to demonstrate that during the past two decades the race relations social science has been telling Americans more about them selves on the historical issue of race-most of which they are reluctant to hear-than any other subfield in recent American intellectual history. -I- For more than five decades historically minded anthropologists and intellectual historians have celebrated the decisive role that Franz Uri Boas played in undermining the racist worldview that prevailed in the social sciences during the years before 1930.1 Surprisingly little of this literature-especially when one considers the amount of data which is readily accessible-deals with Boas's specific treatment of Explorations in Ethnic Studies Vol. -

Santa Claus to Visit the San Bernardino Public Libraries

Inland Empire Community Newspapers • November 28, 2013 • Page A5 Tuskegee Airman Paul E. Green remains proud of his past; lives for tomorrow PHOTO had a specified military mission. COURTESY /R OTARY Segregation would have occurred CLUB in the military without the Free - man Field Mutiny. President Tru - Paul L. Green man signed the executive order was presented demanding equality in 1948." Congressional Green and Buford L. Johnson Medal of Honor in are the only two living authentic Tuskegee Airmen in the greater 2007 by President San Bernardino region. He feels Bush as a gradu - there are many who claim to be ate of Tuskegee members of the Tuskegee Airmen Institute and for who never touched a flight helmet. missions flown in "You can just pay their dues and World War II. you are a member. Many chapter members never finished the flight training program, or were mechan - ics, or were pilots that never flew in combat. I don't have to pay dues to anyone. I finished the Tuskegee Institute flight training program," said Green. He says that there are about 950 By Harvey M. Kahn Green said remaining certified original that he, nor any other Tuskegee Tuskegee Airmen still alive. Until Airmen thought they were doing recently, many talked every Sun - PHOTO COURTESY :modelairplanenews/Paul Reid photo olonel Paul L. Green anything at the time that would day via ham radio. "There are 56 has lived a life akin to a have ramifications for the next 70 chapters of Tuskegee Airmen Former Norton Air Base Commander Paul L. Green pictured on motion picture script. -

Program Ohio Civil Rights Hall of Fame

John Kasich G. Michael Payton Governor Executive Director V|ä|Ä e|z{àá Commissioners: Leonard Hubert, Chair Eddie Harrell, Jr. Stephanie Mercado Tom Roberts Rashmi Yajnik THIRD ANNUAL HALL OF FAME OCTOBER 13, 2011 ROGER ABRAMSON THEODORE M. BERRY KEN CAMPBELL NATHANIEL R. JONES AMOS H. LYNCH LOUIS D. SHARP V. ANTHONY SIMMS-HOWELL 2011 Presenting Sponsor: Founding Sponsors: OHIO CIVIL RIGHTS HALL OF FAME OCTOBER 13, 2011 V|ä|Ä e|z{àá THIRD ANNUAL HALL OF FAME 2011 The Ohio Civil Rights Hall of Fame seeks to acknowledge the citizens who have left their mark in the State of Ohio through their tireless efforts in furthering civil and human rights in their communities. These distinguished individuals have served as beacons making significant strides in support of civil and human rights. Through their exemplary leadership they have helped to eliminate barriers to equal opportunity in this great state as well as foster cultural awareness and understanding for a more just society. OHIO CIVIL RIGHTS HALL OF FAME OCTOBER 13, 2011 g{tÇ~ lÉâ The Ohio Civil Rights Commission wishes to extend our sin- cere appreciation for the tremendous support from each of our sponsors. This program would not be possible without the generosity and creativity provided through our partnership. A special thank you to our committee members: Dr. J. Michael Bernstein, Wright State University Stephen Francis, Honda of America Mfg., Inc. Patricia Cash, PNC Bank Kim Robinson, National Underground Railroad Freedom Center Jackie Wallace, National Underground Railroad Freedom Center October 13, 2011 OHIO CIVIL RIGHTS HALL OF FAME OCTOBER 13, 2011 OHIO CIVIL RIGHTS HALL OF FAME OCTOBER 13, 2011 `|áàÜxáá Éy VxÜxÅÉÇ|xá Angela Pace cares about the community. -

Kaiser Family Foundation/CNN: Survey of Americans on Race

REPORT November 2015 Kaiser Family Foundation/CNN Survey of Americans on Race Prepared by: Bianca DiJulio, Mira Norton, Symone Jackson, and Mollyann Brodie Kaiser Family Foundation In the last couple of years, several incidents in which African Americans were mistreated or in some cases killed by police have sparked renewed public attention to the issue of race relations in America. To better understand the current status of the issue, the Kaiser Family Foundation and CNN surveyed the U.S. public to gauge their views of race in America and personal experiences with discrimination or racism, with a focus on the views and experiences of Black and Hispanic people in America. Racism continues to be a reality for Blacks and Hispanics who report being denied jobs and housing because of their race, or being the victim of unfair treatment in public places like while shopping, dining out, or in dealings with police. Nearly half of Blacks report fearing for their life at some time because of their race. In light of these experiences, there are stark differences in how Blacks, Hispanics and Whites perceive the problem, as well as their attitudes about who is responsible for improving race relations, and views of the criminal justice system’s treatment of Blacks and Hispanics. Recent events have set inequities in the criminal justice system on this national stage and the survey explores views on the underlying reasons for recent protests and support for the Black Lives Matter movement. A third of Black Americans say they have been victims of racial discrimination at some point in their lives, denying them opportunities in housing or employment, and more than 4 in 10 (45 percent) say they have at some point been afraid their life was in danger because of their race. -

The 1945 Black Wac Strike at Ft. Devens DISSERTATION Presented

The 1945 Black Wac Strike at Ft. Devens DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Sandra M. Bolzenius Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2013 Dissertation Committee: Professor Judy Tzu-Chun Wu, Advisor Professor Susan Hartmann Professor Peter Mansoor Professor Tiyi Morris Copyright by Sandra M. Bolzenius 2013 Abstract In March 1945, a WAC (Women’s Army Corps) detachment of African Americans stationed at Ft. Devens, Massachusetts organized a strike action to protest discriminatory treatment in the Army. As a microcosm of military directives and black women’s assertions of their rights, the Ft. Devens strike provides a revealing context to explore connections between state policy and citizenship during World War II. This project investigates the manner in which state policies reflected and reinforced rigid distinctions between constructed categories of citizens, and it examines the attempts of African American women, who stood among the nation’s most marginalized persons, to assert their rights to full citizenship through military service. The purpose of this study is threefold: to investigate the Army’s determination to strictly segment its troops according to race and gender in addition to its customary rank divisions; to explore state policies during the war years from the vantage point of black women; and to recognize the agency, experiences, and resistance strategies of back women who enlisted in the WAC during its first years. The Ft. Devens incident showcases a little known, yet extraordinary event of the era that features the interaction between black enlisted women and the Army’s white elite in accordance with standard military protocol. -

The Importance of Collecting Data and Doing Social Scientific Research on Race ABOUT the AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION

STATEMENT OF THE AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION ON The Importance of Collecting Data and Doing Social Scientific Research on Race ABOUT THE AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION The American Sociological Association (ASA), founded in 1905, is a non-profit membership association dedicated to serving sociologists in their work, advancing sociology as a scientific discipline and profession, and promoting the contributions and use of sociology to society. As the national organization for 13,000 sociologists, the ASA is well positioned to provide a unique set of benefits to its members and to promote the vitality, visibility, and diversity of the discipline. Working at the national and international levels, the Association aims to articulate policy and implement programs likely to have the broadest possible impact for sociology now and in the future. William T. Bielby President Barbara F. Reskin Past-President Michael Burawoy President-Elect Sally T. Hillsman Executive Officer Cite publication as: American Sociological Association. 2003. The Importance of Collecting Data and Doing Social Scientific Research on Race. Washington, DC: American Sociological Association. For Information: American Sociological Association 1307 New York Avenue NW, Suite 700 Washington, DC 20005-4701 Telephone: (202) 383-9005 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.asanet.org Copyright © 2003 by the American Sociological Association The Importance of Collecting Data and Doing Social Scientific Research on Race The question of whether to collect statistics that allow the comparison of differences among racial and ethnic groups in the census, public surveys, and administrative databases is not an abstract one. Some scholarly and civic leaders believe that measuring these differences promotes social divisions and fuels a mistaken perception that race is a biological concept. -

Lyndon Johnson and Albert Gore

historian_88.qxp 20/12/2005 12:54 Page 8 Feature Lyndon Johnson and Albert Gore: — PROFESSOR A.J. BADGER Southern New Dealers And The Modern South LBJ and Albert Two Southern New Dealers Gore, Al’s father, Lyndon Johnson and Albert Gore were elected to Congress within a year of each other in helped to 1937-38. They were elected in the old style of patronage-oriented southern Democratic transform the Party politics in which a plethora of candidates, with few issues to divide them, contested Southern States. primary elections. Both circumvented the local county seat elites who usually delivered their counties' votes by taking their case directly to the people, mounting vigorous campaigns to establish their name recognition. Johnson reached out to the tiniest and most isolated communities in his district and completely overturned the 'leisurely pace normal in Texas elections.' Gore played the fiddle with a small band to attract a crowd on Saturday afternoons in courthouse squares across his district. But if they started their political lives in the traditional, old, rural South, their careers – LBJ till he stood down from the Presidency in 1968 in the face of the intractable war in Vietnam, Gore till he was defeated as the no I target of the Nixon Southern Strategy in 1970 – spanned the creation of the modern South. In no small measure they themselves contributed to the collapse of the poor, rural, white supremacy South and the creation of a prosperous, urban, bi-racial South. Their careers saw the replacement of the props that had underpinned -

Tuskegee Airmen at Oscoda Army Air Field David K

WINTER 2016 - Volume 63, Number 4 WWW.AFHISTORY.ORG know the past .....Shape the Future Our Sponsors Our Donors A Special Thanks to Members for their Sup- Dr Richard P. Hallion port of our Recent Events Maj Gen George B. Harrison, USAF (Ret) Capt Robert Huddleston and Pepita Huddleston Mr. John A. Krebs, Jr. A 1960 Grad Maj Gen Dale Meyerrose, USAF (Ret) Col Richard M. Atchison, USAF (Ret) Lt Gen Christopher Miller The Aviation Museum of Kentucky Mrs Marilyn S. Moll Brig Gen James L. Colwell, USAFR (Ret) Col Bobby B. Moorhatch, USAF (Ret) Natalie W. Crawford Gen Lloyd Fig Newton Lt Col Michael F. Devine, USAF (Ret) Maj Gen Earl G Peck, USAF (Ret) Maj Gen Charles J. Dunlap, Jr., USAF (Ret) Col Frederic H Smith, III, USAF (Ret) SMSgt Robert A. Everhart, Jr., USAF (Ret) Don Snyder Lt Col Raymond Fredette, USAF (Ret) Col Darrel Whitcomb, USAFR (Ret) Winter 2016 -Volume 63, Number 4 WWW.AFHISTORY.ORG know the past .....Shape the Future Features Boyd Revisited: A Great Mind with a Touch of Madness John Andreas Olsen 7 Origins of Inertial Navigation Thomas Wildenberg 17 The World War II Training Experiences of the Tuskegee Airmen at Oscoda Army Air Field David K. Vaughan 25 Ralph S. Parr, Jr., USAF Fighter Pilot Extraordinaire Daniel L. Haulman 41 All Through the Night, Rockwell Field 1923, Where Air-to-Air Refueling Began Robert Bruce Arnold 45 Book Reviews Thor Ballistic Missile: The United States and the United Kingdom in Partnership By John Boyes Review by Rick W. Sturdevant 50 An Illustrated History of the 1st Aero Squadron at Camp Furlong: Columbus, New Mexico 1916-1917 By John L. -

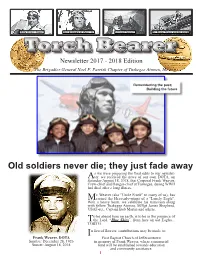

Torch Bearer Newsletterwe Dare 2017 Not - 2018 Fail

Willa Brown, Aviator Col. Benjamin O. Davis, Jr. Ground Support Lt. Roscoe Brown and Sgt Smith Torch Bearer NewsletterWe Dare 2017 Not - 2018 Fail... Edition The Brigadier General Noel F. Parrish Chapter of Tuskegee Airmen, Inc. Remembering the past; Building the future Old soldiers never die; they just fade away s we were preparing the final edits to our newslet- ter, we received the news of our own DOTA, on SaturdayA August 18, 2018, that Corporal Frank Weaver, Crew-chief and Hangar-chief at Tuskegee, during WWII had died after a long illness. r. Weaver (aka "Uncle Frank" to many of us), has earned the Heavenly-wings of a "Lonely Eagle". WithM a heavy heart, we celebrate his transition along with fellow Tuskegee Airmen, M/Sgt James Shepherd, USAF-ret., Captain Bob Martin and others. o be absent here on earth, is to be in the presence of the Lord. “Blue Skies”, from here on out Eagles... TGBTG.T n lieu of flowers, contributions may be made to: Frank Weaver, DOTA I First Baptist Church of Jeffersontown Sunrise: December 28, 1926 in memory of Frank Weaver, where a memorial Sunset: August 18, 2018 fund will be established towards education and community assistance. 1 DOTAs from Kentucky B.G.N.F.P. DOTA Members 1/Lt. Frank “Doug” Wa l ker Flt-Off Alvin LaRue, Sr. Cpl. Frank Weaver P40 Pilot B25 Bombardier/Nav. Hangar Chief 2013 Lonely Eagle 2014 Lonely Eagle 2018 Lonely Eagle Surviving Documented Original Tuskegee Airmen Sgt. William (Wild Bill) Davis, Mechanic, Louisville/Houston Cpl. Virgil Jewell, Crew-chief, Louisville ¼ LONELY EAGLES (Deceased) • B/Gen.