Platform Worlds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meilyne Tran BOOK WALKER Co.Ltd. [email protected] Ph: +81-3-5216-8312

MEDIA CONTACT: Meilyne Tran BOOK WALKER Co.Ltd. [email protected] Ph: +81-3-5216-8312 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE BOOK☆WALKER CELEBRATES ANIME BOSTON WITH GIVEAWAYS, NEW TITLES KADOKAWA's Online Store for Manga & Light Novels MARCH 15, 2016 – BookWalker returns to N. America with its first anime con appearance of 2016 at Anime Boston. Anime Boston will be held on March 25-27 at the Hynes Convention Center in Boston, Massachusetts. Manga and light novel readers, visit booth #308 for your chance to win prizes, like Sword Art Online, Fate/ and Kill La Kill figures, limited edition Sword Art Online clear file folders, or a $10 gift card good toward purchasing any digital manga or light novel title on BookWalker Global. WIN PRIZES FROM BOOKWALKER AT ANIME BOSTON There are several ways to win! If you’re new to BookWalker, just visit http://global.bookwalker.jp and subscribe to our mailing list. Show your “My Account” page to BookWalker booth staff at Anime Boston, and you’ll get a chance to try for one of the prizes. For a second chance to win, use your $10 gift card to purchase any eBook on BookWalker. Want another chance to take home a prize? Take a photo at the BookWalker booth, follow BookWalker on Twitter at @BOOKWALKER_GL and post your photo on Twitter with the hashtags #AnimeBoston and #BOOKWALKER. Show your tweet to BookWalker booth staff, and you’ll get a chance to win one of three Neon Genesis Evangelion figures. Haven’t tried BookWalker yet? Anime Boston is also your chance to get a hands-on look at our eBook store. -

Holdings Inc

Annual Report 2011 NAMCO BANDAI Holdings Inc. The BANDAI NAMCO Group develops entertainment products and services in a wide range of fields, including toys, arcade game machines, game software, visual and music software, and amusement facilities. By building a strong operational foundation in the domestic market, as well as aggressively developing operations in overseas markets to secure future growth, we aim to be a “Globally Recognized Entertainment Group.” Our Mission Statement Dreams, Fun and Inspiration “Dreams, Fun and Inspiration” are the Engine of Happiness. Through our entertainment products and services, BANDAI NAMCO will continue to provide “Dreams, Fun and Inspiration” to people around the world, based on our boundless creativity and enthusiasm. Our Vision The Leading Innovator in Global Entertainment As an entertainment leader across the ages, BANDAI NAMCO is constantly exploring new areas and heights in entertainment. We aim to be loved by people who have fun and will earn their trust as “the Leading Innovator in Global Entertainment.” The Point BANDAI NAMCO Group Annual Report 2011: Key Points This annual report explains the initiatives implemented by the Group in FY 2011.3 and the Group’s management policies and business strategies in FY 2012.3. Progress with the Restart Plan The Restart Plan was launched in April 2010 with the objective of bolstering the Group’s operational foundation to support the implementation of the current Mid-term Business Plan. This section describes the progress that has been made with the Restart Plan. Page 14: Message from the President Second Year of the Current Mid-term Business Plan Targeting the preparation of a foundation for global growth, the Group advanced the Restart Plan and implemented a range of initiatives. -

Obal.Bookw Walker.Jp/ MED BOOK W Pr‐Gl

MEDIA CONTACT: Norika Suzuki BOOK WALKER Co.Ltd. pr‐[email protected] Ph: +81‐3‐5216‐8312 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE BOOK☆WALKER UNVEILS SITE REDESIGN & NEW TITLES AT NYCC 2015 KADOKAWA's Online Store for Manga & Light Novels direct from Japan OCTOBER 6, 2015 – Attention New York Comic‐Con attendees! Drop by the BookWalker booth at NYCC (#854) for your chance to win prizes! You'll also get a hands‐on look at our updated eBook store with over 800 comics and light novels in English, with many titles exclusive to BookWalker. PREVIEW: NEW BOOK☆WALKER MANGA TITLES AVAILABLE SOON New manga titles that will be available after October 28, 2015 include: MAOYU : Archenemy and Hero "Become mine, Hero" "I refuse!" vol. 14 by Akira Ishida and Mamare Touno **BookWalker Exclusive** The story that captivated a million people is now a comic! NINJA SLAYER vol. 4 by Bradley Bond and Philip "Ninj@" Morzez **BookWalker Exclusive** Running through the darkness, killing with karate skills! A refined ninja comic! MARIA HOLIC vol. 14 by Minari Endou **BookWalker Exclusive** A new type of pretty‐girl screwball romantic comedy with a yuri twist, featuring Kanako, a girl who's more than a little into other girls, and Mariya, a super‐sadistic boy in disguise! More will be added every month. Follow BookWalker on our new Facebook and Twitter pages for updates on new titles and special promotions. Find us on Facebook at: https://www.facebook.com/bookwalkerglobal Follow us on Twitter at @BOOKWALKER_GL https://twitter.com/BOOKWALKER_GL BookWalker manga and light novel titles in English are currently available for purchase in ALL countries worldwide without region restrictions. -

Conference Booklet

30th Oct - 1st Nov CONFERENCE BOOKLET 1 2 3 INTRO REBOOT DEVELOP RED | 2019 y Always Outnumbered, Never Outgunned Warmest welcome to first ever Reboot Develop it! And we are here to stay. Our ambition through Red conference. Welcome to breathtaking Banff the next few years is to turn Reboot Develop National Park and welcome to iconic Fairmont Red not just in one the best and biggest annual Banff Springs. It all feels a bit like history repeating games industry and game developers conferences to me. When we were starting our European older in Canada and North America, but in the world! sister, Reboot Develop Blue conference, everybody We are committed to stay at this beautiful venue was full of doubts on why somebody would ever and in this incredible nature and astonishing choose a beautiful yet a bit remote place to host surroundings for the next few forthcoming years one of the biggest worldwide gatherings of the and make it THE annual key gathering spot of the international games industry. In the end, it turned international games industry. We will need all of into one of the biggest and highest-rated games your help and support on the way! industry conferences in the world. And here we are yet again at the beginning, in one of the most Thank you from the bottom of the heart for all beautiful and serene places on Earth, at one of the the support shown so far, and even more for the most unique and luxurious venues as well, and in forthcoming one! the company of some of the greatest minds that the games industry has to offer! _Damir Durovic -

STOXX Asia 1200 Last Updated: 02.01.2018

STOXX Asia 1200 Last Updated: 02.01.2018 Rank Rank (PREVIOUS ISIN Sedol RIC Int.Key Company Name Country Currency Component FF Mcap (BEUR) (FINAL) ) KR7005930003 6771720 005930.KS KR002D Samsung Electronics Co Ltd KR KRW Y 236.0 1 1 TW0002330008 6889106 2330.TW TW001Q TSMC TW TWD Y 155.9 2 2 JP3633400001 6900643 7203.T 690064 Toyota Motor Corp. JP JPY Y 144.0 3 3 HK0000069689 B4TX8S1 1299.HK HK1013 AIA GROUP HK HKD Y 85.6 4 5 JP3902900004 6335171 8306.T 659668 Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group JP JPY Y 80.5 5 4 CNE1000002H1 B0LMTQ3 0939.HK CN0010 CHINA CONSTRUCTION BANK CORP H CN HKD Y 65.7 6 6 JP3436100006 6770620 9984.T 677062 Softbank Group Corp. JP JPY Y 57.3 7 8 JP3735400008 6641373 9432.T 664137 Nippon Telegraph & Telephone C JP JPY Y 55.5 8 7 JP3854600008 6435145 7267.T 643514 Honda Motor Co. Ltd. JP JPY Y 51.7 9 9 JP3890350006 6563024 8316.T 656302 Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Grou JP JPY Y 50.9 10 12 INE040A01026 B5Q3JZ5 HDBK.BO IN00CH HDFC Bank Ltd IN INR Y 49.9 11 10 JP3435000009 6821506 6758.T 682150 Sony Corp. JP JPY Y 47.5 12 11 CNE1000003G1 B1G1QD8 1398.HK CN0021 ICBC H CN HKD Y 47.5 13 14 HK0941009539 6073556 0941.HK 607355 China Mobile Ltd. CN HKD Y 47.2 14 13 CNE1000003X6 B01FLR7 2318.HK CN0076 PING AN INSUR GP CO. OF CN 'H' CN HKD Y 44.6 15 20 JP3236200006 6490995 6861.T 649099 Keyence Corp. -

Code Issue Size 1 1301 KYOKUYO CO.,LTD. Topixsmall TOPIX1000

TOPIX New Index Series (As end of October , 2012) (sort by Local Code) As of October 5, 2012 Code Issue TOPIX New Index Series Size 1 1301 KYOKUYO CO.,LTD. TOPIXSmall TOPIX1000 小型 2 1332 Nippon Suisan Kaisha,Ltd. TOPIX Mid400 TOPIX 500 TOPIX1000 中型 3 1334 Maruha Nichiro Holdings,Inc. TOPIX Mid400 TOPIX 500 TOPIX1000 中型 4 1352 HOHSUI CORPORATION TOPIXSmall 小型 5 1377 SAKATA SEED CORPORATION TOPIXSmall TOPIX1000 小型 6 1379 HOKUTO CORPORATION TOPIXSmall TOPIX1000 小型 7 1414 SHO-BOND Holdings Co.,Ltd. TOPIXSmall TOPIX1000 小型 8 1417 MIRAIT Holdings Corporation TOPIXSmall TOPIX1000 小型 9 1514 Sumiseki Holdings,Inc. TOPIXSmall 小型 10 1515 Nittetsu Mining Co.,Ltd. TOPIXSmall TOPIX1000 小型 11 1518 MITSUI MATSUSHIMA CO.,LTD. TOPIXSmall TOPIX1000 小型 12 1605 INPEX CORPORATION TOPIX Large70 TOPIX 100 TOPIX 500 TOPIX1000 大型 13 1606 Japan Drilling Co.,Ltd. TOPIXSmall 小型 14 1661 Kanto Natural Gas Development Co.,Ltd. TOPIXSmall TOPIX1000 小型 15 1662 Japan Petroleum Exploration Co.,Ltd. TOPIX Mid400 TOPIX 500 TOPIX1000 中型 16 1712 Daiseki Eco.Solution Co.,Ltd. TOPIXSmall 小型 17 1719 HAZAMA CORPORATION TOPIXSmall TOPIX1000 小型 18 1720 TOKYU CONSTRUCTION CO., LTD. TOPIXSmall 小型 19 1721 COMSYS Holdings Corporation TOPIX Mid400 TOPIX 500 TOPIX1000 中型 20 1722 MISAWA HOMES CO.,LTD. TOPIXSmall TOPIX1000 小型 21 1762 TAKAMATSU CONSTRUCTION GROUP CO.,LTD. TOPIXSmall 小型 22 1766 TOKEN CORPORATION TOPIXSmall TOPIX1000 小型 23 1780 YAMAURA CORPORATION TOPIXSmall 小型 24 1801 TAISEI CORPORATION TOPIX Mid400 TOPIX 500 TOPIX1000 中型 25 1802 OBAYASHI CORPORATION TOPIX Mid400 TOPIX 500 TOPIX1000 中型 26 1803 SHIMIZU CORPORATION TOPIX Mid400 TOPIX 500 TOPIX1000 中型 27 1805 TOBISHIMA CORPORATION TOPIXSmall TOPIX1000 小型 28 1808 HASEKO Corporation TOPIX Mid400 TOPIX 500 TOPIX1000 中型 29 1810 MATSUI CONSTRUCTION CO.,LTD. -

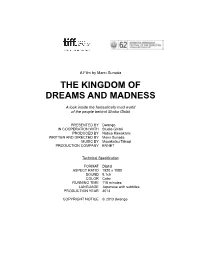

The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness

A Film by Mami Sunada THE KINGDOM OF DREAMS AND MADNESS A look inside the fantastically mad world of the people behind Studio Ghibli PRESENTED BY Dwango IN COOPERATION WITH Studio Ghibli PRODUCED BY Nobuo Kawakami WRITTEN AND DIRECTED BY Mami Sunada MUSIC BY Masakatsu Takagi PRODUCTION COMPANY ENNET Technical Specification FORMAT Digital ASPECT RATIO 1920 x 1080 SOUND 5.1ch COLOR Color RUNNING TIME 118 minutes LANGUAGE Japanese with subtitles PRODUCTION YEAR 2013 COPYRIGHT NOTICE © 2013 dwango ABOUT THE FILM There have been numerous documentaries about Studio Ghibli made for television and for DVD features, but no one had ever conceived of making a theatrical documentary feature about the famed animation studio. That is precisely what filmmaker Mami Sunada set out to do in her first film since her acclaimed directorial debut, Death of a Japanese Salesman. With near-unfettered access inside the studio, Sunada follows the key personnel at Ghibli – director Hayao Miyazaki, producer Toshio Suzuki and the elusive “other” director, Isao Takahata – over the course of approximately one year as the studio rushes to complete their two highly anticipated new films, Miyazaki’s The Wind Rises and Takahata’s The Tale of The Princess Kaguya. The result is a rare glimpse into the inner workings of one of the most celebrated animation studios in the world, and a portrait of their dreams, passion and dedication that borders on madness. DIRECTOR: MAMI SUNADA Born in 1978, Mami Sunada studied documentary filmmaking while at Keio University before apprenticing as a director’s assistant under Hirokazu Kore-eda and others. -

Danganronpa: the Animation Volume 2 Online

aCP7m (Read now) Danganronpa: The Animation Volume 2 Online [aCP7m.ebook] Danganronpa: The Animation Volume 2 Pdf Free Spike Chunsoft, Takashi Tsukimi ebooks | Download PDF | *ePub | DOC | audiobook Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #75963 in Books Chunsoft Spike 2016-08-09 2016-08-09Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 7.20 x .60 x 5.10l, .0 #File Name: 1616559632192 pagesDanganronpa The Animation Volume 2 | File size: 31.Mb Spike Chunsoft, Takashi Tsukimi : Danganronpa: The Animation Volume 2 before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Danganronpa: The Animation Volume 2: 0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Saw the anime, have the video games, now ...By Joshua ComeauxSaw the anime, have the video games, now obtaining the manga to complete my collection! arrived in a timely manner and was undamaged.THANK YOU0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. awesome!By Bella Giorgicame as soon as it was released and was great quality!! its just like the games!!1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. This is totally psycho! Murder and mayhem. So ...By Nicola MansfieldThis is totally psycho! Murder and mayhem. So much stuff happens in this volume my mind is reeling. The characters in this series are downright pathological with some really weird stuff being revealed in this volume. The book ends with another trial about to begin. Having lived through the first round of judgment in the trap that is Hope's Peak Academy, bonds are beginning to form among the surviving students. -

Notice of the 11Th Annual Meeting of Shareholders

Securities Code: 3635 June 2, 2020 To Our Shareholders: 1-18-12 Minowa-cho, Kouhoku-ku, Yokohama-shi, Kanagawa KOEI TECMO HOLDINGS CO., LTD. Yoichi Erikawa, President & CEO (Representative Director) Notice of the 11th Annual Meeting of Shareholders The Company hereby notifies shareholders that the 11th Annual Meeting of Shareholders will be held as described below. Recently, self-restraint of leaving home has been requested by the government and prefectural governors to prevent the spread of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). As a result of due consideration to the given situation, we have decided to hold the Annual Meeting of Shareholders following appropriate measures to prevent infection. Also, considering the situation in which self-restraint of leaving home is requested, we strongly suggest that, from the perspective of preventing the spread of infection, you exercise your voting rights in writing or by electromagnetic means (such as on the Internet) in advance if at all possible for this Annual Meeting of Shareholders, and refrain from attending on the date concerned. We kindly request you read the following Reference Document for the Annual Meeting of Shareholders, and exercise your voting rights by any of the methods described in the “Information on Exercise of Voting Right” (pages5 and 6) no later than Wednesday, June 17, 2020 at 6:00 p.m. Date: Thursday, June 18, 2020 at 10:00 a.m. Venue: 3-7 Minatomirai 2-chome, Nishi-ku, Yokohama-shi, Kanagawa The Yokohama Bay Hotel Tokyu 2nd basement, Ambassador’s Ballroom (Please see the “Venue Information Map for the Annual Meeting of Shareholders.”) Purposes: Items to be reported: 1. -

Smart AI City Sapporo

jobkita Smart AI City Sapporo The key players in open innovation he smart city concept aims to build next-generation trans- 02 Introduction Contents - 7 keywords to know Sapporo ���������� �������� ���� ���� ������� ����������� ��� ���������� T 04 Foreword - Katsuhiro Akimoto, Mayor, cutting-edge technology. Cities around the world are conducting Sapporo City research and demonstration tests in order to make themselves The key players in open innovation attractive, improve the quality of life, and realize sustainable so- Sapporo AI Lab 06 cieties. Hidenori Kawamura, Professor, Hokkaido University Big data, IoT (*), and cloud solutions are key to the smart city 09 Takuya Nakamura, Representative Director, concept. AI (*) in particular is attracting attention with such tech- CHOWA GIKEN Corporation nologies. Sapporo Innovation Lab Sapporo, the central city of Hokkaido, has a population of 12 Takashi Ishida, Representative Director, Technoface Corporation 1.97 million. This city has many AI researchers and companies 15 Looking at Sapporo through the data, Business edition actively using AI. In addition, next-generation town development Sapporo City University AI Lab through industry-academia-government collaboration has been 16 Hideyuki Nakashima, President, accelerating, a base has been born with a “hub function” con- Sapporo City University necting engineers together. 19 Takuya Irisawa, Representative Director, Open innovation integrates diverse knowledge under the Ecomott Inc. Hokkaido-like broad-minded terrain. The main characters will be SARD (Sapporo Area Regional Data Utilization Organization) 22 introduced in this book. Taro Kamioka, Professor, Hitotsubashi University �������������������������������������������������������� 25 Looking at Sapporo through the data, Living edition 26 Hidekatsu Hanai, Representative Director & Chairman, Fusion Co., Ltd. IoT Acceleration Sapporo City Lab 29 Kentaro Matsui, Representative Director, ��������������������� Next-generation city SAPPORO 32 Atsushi Uryu, Representative Director, BarnardSoft Co., Ltd. -

The Interface Affect of a Contact Zone: Danmaku on Video-Streaming Platforms

Asiascape: Digital Asia 4 (2017) 233-256 brill.com/dias The Interface Affect of a Contact Zone: Danmaku on Video-Streaming Platforms Jinying Li Assistant professor of Film Studies in the English Department, University of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania [email protected] Abstract This essay interrogates the transmedial, transnational expansion of platforms by ana- lyzing the mediation functions and affective experiences of a discursive interface, dan- maku. It is a unique interface design originally featured by the Japanese video-sharing platform Niconico to render user comments flying over videos on screen. The dan- maku interface has been widely adopted in China by video-streaming websites, social media, and theatrical film exhibitions. Examining the fundamental incoherence that is structured by the interface – the incoherence between content and platform, between the temporal experiences of pseudo-live-ness and spectral past – the paper underlines the notion of ‘contact’ as the central logic of platforms and argues that dan- maku functions as a volatile contact zone among conflicting modes, logics, and struc- tures of digital media. Such contested contacts generate affective intensity of media regionalism, in which the transmedial/transnational processes managed by platforms in material/textual traffic are mapped by the flow of affect on the interface. Keywords Chinese media culture – platform – danmaku (danmu) – digital media – interface – media theory. In a transnational media context, what drives the flow of culture and com- modities, as many have argued, is no longer the content but the platform – that is, the global expansion of networked mediatory systems, such as Google, Facebook, and Apple iOS. But this process of transnational expansion of © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, ���7 | doi �0.��63/���4�3��-��340079Downloaded from Brill.com09/25/2021 10:22:24PM via free access 234 Li platforms is neither smooth nor homogeneous. -

Participating Companies & Brands Exhibitor / Sponsor

PARTICIPATING COMPANIES & BRANDS EXHIBITOR / SPONSOR BOOTH COUNTRY / REGION 3DS Co., Ltd. / 株式会社スリー・ディー・エス G-11 Japan Abacus Inc. / 株式会社アバクス N-15 Japan ACM SIGGRAPH Bangkok Chapter / M-26 Thailand バンコクACMシーグラフ Adobe Research Program Sponsor - United States of America AeRO L-30 Australia Aeroprobing Inc. M-11 Taiwan Allied Brains, Inc. Program Sponsor - Japan AMD Program Sponsor - Japan ArchiveTips, Inc / P-13 Japan アーカイブティップス株式会 社 ASK Corporation K-13 Japan ASTRODESIGN, Inc. / アストロデザイン株式会社 N-14 Japan ASVDA (Asia Silicon Valley Development Agency) M-11 Taiwan ATAPY Co., Ltd. / アタピー M-26 Thailand Augmented Intelligence M-8 United States of America Autodesk Ltd. / オートデスク株式会社 Program Sponsor - Japan AWS Thinkbox P-7 Canada BANDAI NAMCO Studios Inc. / Bronze Sponsor N-16 Japan 株式会社バンダイナムコスタジオ BinaryVR, Inc. M-6 United States of America BLAST Inc. / 株式会社ブラスト N-3 Japan Bros Inc. - Imaging Group / 株式会社ブロス N-13 Japan Bunkyo University / 文教大学 N-20 Japan L-29/M-29/N- Busan IT Industry Promotion Agency South Korea 29 C2 Monster P-6 South Korea Digital Projection Canon - Japan Sponsor CELSYS,Inc. / 株式会社セルシス K-5 Japan CGVisual.com (Animazu Studios) P-3 Hong Kong SAR Chengdu ACM SIGGRAPH Chapter M-1 China CLO Virtual Fashion Inc J-8 South Korea College of Image Arts and Sciences, Ritsumeikan University / N-19 Japan 立命館大学 映像学部 Computer Vision Research Center of National Chiao Tung M-11 Taiwan University CyberAgent, Inc. / 株式会社サイバーエージェント Gold Sponsor G-8 / Job Fair Japan Daegu Convention & Visitors Bureau J-1 South Korea Dell Japan Inc. / デル株式会社 I-4 Japan DeNA Co., Ltd. / 株式会社ディー・エヌ・エー Bronze Sponsor - Japan Digi Space Co., Ltd M-8 Taiwan Digital Content Association of Japan / N-25 Japan 一般財団法人デジタルコンテンツ協会 Digital Design STUDIO Ltd.