Justice Breyer's Triumph in the Third Battle Over the Second Amendment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trump Judges: Even More Extreme Than Reagan and Bush Judges

Trump Judges: Even More Extreme Than Reagan and Bush Judges September 3, 2020 Executive Summary In June, President Donald Trump pledged to release a new short list of potential Supreme Court nominees by September 1, 2020, for his consideration should he be reelected in November. While Trump has not yet released such a list, it likely would include several people he has already picked for powerful lifetime seats on the federal courts of appeals. Trump appointees' records raise alarms about the extremism they would bring to the highest court in the United States – and the people he would put on the appellate bench if he is reelected to a second term. According to People For the American Way’s ongoing research, these judges (including those likely to be on Trump’s short list), have written or joined more than 100 opinions or dissents as of August 31 that are so far to the right that in nearly one out of every four cases we have reviewed, other Republican-appointed judges, including those on Trump’s previous Supreme Court short lists, have disagreed with them.1 Considering that every Republican president since Ronald Reagan has made a considerable effort to pick very conservative judges, the likelihood that Trump could elevate even more of his extreme judicial picks raises serious concerns. On issues including reproductive rights, voting rights, police violence, gun safety, consumer rights against corporations, and the environment, Trump judges have consistently sided with right-wing special interests over the American people – even measured against other Republican-appointed judges. Many of these cases concern majority rulings issued or joined by Trump judges. -

The Federalist Society for Law and Public Policy Studies 2009 Annual Report

The Federalist Society for Law and Public Policy Studies 2009 Annual Report “The Courts must declare the sense of the law; and if they should be disposed to exercise will instead of JUDGMENT, the consequences would be the substitution of their pleasure for that of the legislative body.” The Federalist 78 THE FEDERALIST SOCIETY aw schools and the legal profession are currently strongly dominated by a L form of orthodox liberal ideology which advocates a centralized and uniform society. While some members of the academic community have dissented from these views, by and large they are taught simultaneously with (and indeed as if they were) the law. The Federalist Society for Law and Public Policy Studies is a group of conservatives and libertarians interested in the current state of the legal order. It is founded on the principles that the state exists to preserve freedom, that the separation of governmental powers is central to our Constitution, and that it is emphatically the province and duty of the judiciary to say what the law is, not what it should be. The Society seeks both to promote an awareness of these principles and to further their application through its activities. This entails reordering priorities within the legal system to place a premium on individual liberty, traditional values, and the rule of law. It also requires restoring the recognition of the importance of these norms among lawyers, judges, law students and professors. In working to achieve these goals, the Society has created a conservative intellectual network that extends to all levels of the legal community. -

Ted Cruz Promoted Himself and Conservative Causes As Texas’ Solicito

FORMER STATE SOLICITORS GENERAL AND OTHER STATE AG OFFICE ATTORNEYS WHO ARE ACTIVE JUDGES by Dan Schweitzer, Director and Chief Counsel, Center for Supreme Court Advocacy, National Association of Attorneys General March 18, 2021 Former State Solicitors General (and Deputy Solicitors General) Federal Courts of Appeals (11) Jeffrey Sutton – Sixth Circuit (Ohio SG) Timothy Tymkovich – Tenth Circuit (Colorado SG) Kevin Newsom – Eleventh Circuit (Alabama SG) Allison Eid – Tenth Circuit (Colorado SG) James Ho – Fifth Circuit (Texas SG) S. Kyle Duncan – Fifth Circuit (Louisiana SG) Andrew Oldham – Fifth Circuit (Texas Deputy SG) Britt Grant – Eleventh Circuit (Georgia SG) Eric Murphy – Sixth Circuit (Ohio SG) Lawrence VanDyke – Ninth Circuit (Montana and Nevada SG) Andrew Brasher – Eleventh Circuit (Alabama SG) State High Courts (6) Stephen McCullough – Virginia Supreme Court Nels Peterson – Georgia Supreme Court Gregory D’Auria – Connecticut Supreme Court John Lopez – Arizona Supreme Court Sarah Warren – Georgia Supreme Court Monica Marquez – Colorado Supreme Court (Deputy SG) State Intermediate Appellate Courts (8) Kent Cattani – Arizona Court of Appeals Karen King Mitchell – Missouri Court of Appeals Kent Wetherell – Florida Court of Appeals (Deputy SG) Scott Makar – Florida Court of Appeals Timothy Osterhaus – Florida Court of Appeals Peter Sacks – Massachusetts Court of Appeals Clyde Wadsworth – Hawaii Intermediate Court of Appeals Gordon Burns – California Court of Appeal (Deputy SG) Federal District Court (11) Gary Feinerman – Northern -

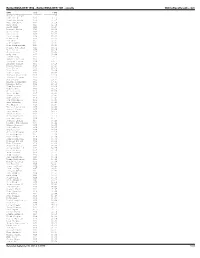

Bolderboulder 10K Results

BolderBOULDER 1994 - BolderBOULDER 10K - results OnlineRaceResults.com NAME DIV TIME ---------------------- ------- ----------- Matthew Lavigne 22 John Mirth M32 31:11 Jonathan Heese M36 31:37 Matt Schubert M24 31:58 Glen Mays M24 31:59 Brett Burt M28 32:07 Rodolfo Gomez M43 32:16 Chris Prior M34 32:21 Scott Kent M27 32:27 Darrin Rohr M29 32:30 Steve Roch M30 32:43 Rob Welo M30 32:43 John Ingram M22 32:44 John Pendergraft M27 32:45 Gerard Ostheimer M25 32:52 Mark Allen M36 32:56 Chris Severy M17 33:08 Andy Ames M31 33:09 Daniel King M34 33:10 Ignacio Morales M42 33:11 Richard Bishop M36 33:12 Brendan Reilly M34 33:16 Aaron Salomon M18 33:17 Dave Nelson M32 33:18 Rick Ames M33 33:26 Dennis Lima M32 33:33 Michael McCarrick M28 33:38 Michael Trunkes M31 33:43 Joe Sheely M35 33:44 Wilbur Ferdinand M32 33:47 Ricardo Rojas M42 33:50 Jeff Rosenow M37 33:52 Robert Love M30 33:54 Chris Borton M18 33:56 Marc Reider M27 34:01 Jason Porter M24 34:03 Sean Coster M18 34:04 Jon Schoenberg M31 34:05 Troy Pickett M31 34:06 Joe Wilson M18 34:07 Michael Sandrock M36 34:08 James Johnson M25 34:09 Bern Gever M34 34:11 Kevin Hilton M22 34:13 Chris Harrison M30 34:15 Lee Stringer M26 34:17 Douglas Hugill M33 34:20 Dominic Wyzomirski M34 34:22 Edward Boggess M36 34:23 John Wiberg M26 34:25 Andrew Crook M35 34:26 Chris Rodriguez M25 34:27 Allan Kupczak M33 34:28 Alex Furman M16 34:29 Daniel Hanewall M32 34:30 Mohamed Hajoui M32 34:32 Zeke Tiernan M18 34:33 Jason Nicholas M24 34:34 Jerry Duckworth M32 34:35 Parrick Aris M37 34:36 Thom Richman M39 34:37 Todd Reeser -

Senate Section (PDF929KB)

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 109 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 151 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, MAY 19, 2005 No. 67 Senate The Senate met at 9:30 a.m. and was ceed to executive session for the con- Yesterday, 21 Senators—evenly di- called to order by the President pro sideration of calendar No. 71, which the vided, I believe 11 Republicans and 10 tempore (Mr. STEVENS). clerk will report. Democrats—debated for over 10 hours The legislative clerk read the nomi- on the nomination of Priscilla Owen. PRAYER nation of Priscilla Richman Owen, of We will continue that debate—10 hours The Chaplain, Dr. Barry C. Black, of- Texas, to be United States Circuit yesterday—maybe 20 hours, maybe 30 fered the following prayer: Judge for the Fifth Circuit. hours, and we will take as long as it Let us pray. RECOGNITION OF THE MAJORITY LEADER takes for Senators to express their God of grace and glory, open our eyes The PRESIDENT pro tempore. The views on this qualified nominee. to the power You provide for all of our majority leader is recognized. But at some point that debate should challenges. Give us a glimpse of Your SCHEDULE end and there should be a vote. It ability to do what seems impossible, to Mr. FRIST. Mr. President, today we makes sense: up or down, ‘‘yes’’ or exceed what we can request or imagine. will resume executive session to con- ‘‘no,’’ confirm or reject; and then we Encourage us again with Your promise sider Priscilla Owen to be a U.S. -

Justice Kennedy Retires; Confirmation Frenzy Ensues a Battle Over the Ideological Future of the U.S

315 W. 11TH AVE., DENVER, CO 80204 | 720–328–1418 | WWW.LAW WEEK COLORADO.COM VOL. 16 | NO. 27 | $6 | JULY 2, 2018 Justice Kennedy Retires; Confirmation Frenzy Ensues A battle over the ideological future of the U.S. Supreme Court is now underway following Justice Anthony Kennedy stepping down last week BY CHRIS OUTCALT mation battle than there was over Jus- nedy is a moderate conservative who rights. “To be honest, “I think they’ll LAW WEEK COLORADO tice Gorsuch.” upset hardline conservatives with his make this an appointment about Roe Following the sudden death of willingness to protect reproductive V. Wade, which it arguably is,” Chen Supreme Court Justice Anthony Justice Antonin Scalia in 2016, Sen- freedoms, marriage equality, and some said. “I think that will be one of the Kennedy punctuated an already rous- ate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell prisoner rights.” mobilizing forces to get more peo- ing end to the court’s session last successfully blocked then-President In making past Supreme Court se- ple to care about this particular ap- week — which included a 5-4 decision Barack Obama’s nominee, Justice Mer- lections, presidents have taken into pointment.” A battle on those terms, upholding President Donald Trump’s rick Garland, refusing to hold hearings account factors such as a candidate’s Chen suggested, could put pressure travel ban and another knocking pub- or even meet with Garland. McConnell background as well as geographic on moderate women in the Senate. lic-sector unions — by announcing frequently argued that the vacant seat and professional diversity. Chen said Back in 1992, Justice Kennedy sided his retirement. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 109 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 109 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 151 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, MAY 19, 2005 No. 67 Senate The Senate met at 9:30 a.m. and was ceed to executive session for the con- Yesterday, 21 Senators—evenly di- called to order by the President pro sideration of calendar No. 71, which the vided, I believe 11 Republicans and 10 tempore (Mr. STEVENS). clerk will report. Democrats—debated for over 10 hours The legislative clerk read the nomi- on the nomination of Priscilla Owen. PRAYER nation of Priscilla Richman Owen, of We will continue that debate—10 hours The Chaplain, Dr. Barry C. Black, of- Texas, to be United States Circuit yesterday—maybe 20 hours, maybe 30 fered the following prayer: Judge for the Fifth Circuit. hours, and we will take as long as it Let us pray. RECOGNITION OF THE MAJORITY LEADER takes for Senators to express their God of grace and glory, open our eyes The PRESIDENT pro tempore. The views on this qualified nominee. to the power You provide for all of our majority leader is recognized. But at some point that debate should challenges. Give us a glimpse of Your SCHEDULE end and there should be a vote. It ability to do what seems impossible, to Mr. FRIST. Mr. President, today we makes sense: up or down, ‘‘yes’’ or exceed what we can request or imagine. will resume executive session to con- ‘‘no,’’ confirm or reject; and then we Encourage us again with Your promise sider Priscilla Owen to be a U.S. -

The Current Status of D.R. Horton, Pending Appellate Litigation, and Predictions of Supreme Court Review

Hofstra Labor & Employment Law Journal Volume 34 | Issue 1 Article 5 9-1-2016 The urC rent Status of D.R. Horton, Pending Appellate Litigation, and Predictions of Supreme Court Review Irene A. Zoupaniotis Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/hlelj Part of the Labor and Employment Law Commons Recommended Citation Zoupaniotis, Irene A. (2016) "The urC rent Status of D.R. Horton, Pending Appellate Litigation, and Predictions of Supreme Court Review," Hofstra Labor & Employment Law Journal: Vol. 34 : Iss. 1 , Article 5. Available at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/hlelj/vol34/iss1/5 This document is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hofstra Labor & Employment Law Journal by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Zoupaniotis: The Current Status of D.R. Horton, Pending Appellate Litigation, THE CURRENT STATUS OF D.R. HORTON, PENDING APPELLATE LITIGATION, AND PREDICTIONS OF SUPREME COURT REVIEW Irene A. Zoupaniotis* I. INTRODUCTION Enforcement of arbitration agreements and class-action waivers has been consistently upheld by the Supreme Court's construction and interpretation of the Federal Arbitration Act ("FAA"). Indeed, the Court has generally found that resolution of claims as a class is a procedural, not substantive, right and that as such, class action waivers are enforceable under the FAA. Unlike the cases that have been decided by the Supreme Court to date, the National Labor Relations Act ("NLRA") protects employees' right to act in concert for the protection of their interests. -

Are More Judges Always the Answer? Hearing Committee

ARE MORE JUDGES ALWAYS THE ANSWER? HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED THIRTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION OCTOBER 29, 2013 Serial No. 113–53 Printed for the use of the Committee on the Judiciary ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://judiciary.house.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 85–282 PDF WASHINGTON : 2014 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY BOB GOODLATTE, Virginia, Chairman F. JAMES SENSENBRENNER, JR., JOHN CONYERS, JR., Michigan Wisconsin JERROLD NADLER, New York HOWARD COBLE, North Carolina ROBERT C. ‘‘BOBBY’’ SCOTT, Virginia LAMAR SMITH, Texas MELVIN L. WATT, North Carolina STEVE CHABOT, Ohio ZOE LOFGREN, California SPENCER BACHUS, Alabama SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas DARRELL E. ISSA, California STEVE COHEN, Tennessee J. RANDY FORBES, Virginia HENRY C. ‘‘HANK’’ JOHNSON, JR., STEVE KING, Iowa Georgia TRENT FRANKS, Arizona PEDRO R. PIERLUISI, Puerto Rico LOUIE GOHMERT, Texas JUDY CHU, California JIM JORDAN, Ohio TED DEUTCH, Florida TED POE, Texas LUIS V. GUTIERREZ, Illinois JASON CHAFFETZ, Utah KAREN BASS, California TOM MARINO, Pennsylvania CEDRIC RICHMOND, Louisiana TREY GOWDY, South Carolina SUZAN DelBENE, Washington MARK AMODEI, Nevada JOE GARCIA, Florida RAUL LABRADOR, Idaho HAKEEM JEFFRIES, New York BLAKE FARENTHOLD, Texas GEORGE HOLDING, North Carolina DOUG COLLINS, Georgia RON DeSANTIS, Florida JASON T. SMITH, Missouri SHELLEY HUSBAND, Chief of Staff & General Counsel PERRY APELBAUM, Minority Staff Director & Chief Counsel (II) C O N T E N T S OCTOBER 29, 2013 Page OPENING STATEMENT The Honorable Bob Goodlatte, a Representative in Congress from the State of Virginia, and Chairman, Committee on the Judiciary ................................ -

Judicial Nominations President Bush's Confirmed Judicial

http://leahy.senate.gov/issues/nominations/index.html Judicial Nominations "The Constitution requires that the President seek the Senate’s advice and consent in making appointments to the federal courts. As a senator and as the Democratic leader of the Senate Judiciary Committee, I take this responsibility very seriously." -- Senator Patrick Leahy, Chairman, Senate Judiciary Committee 316 Of President Bush's Article III Judicial Nominees Have Been Confirmed. (As of September 29, 2008) Read a complete list of President Bush's confirmed nominees. http://leahy.senate.gov/issues/nominations/confirmednominees.htm President Bush's Confirmed Judicial Nominations Court of Supreme Court Circuit Court District Court International Nominees Nominees Nominees Trade As of September 29, 2008 Supreme Court Nominees 2. Samuel A. Alito, Associate Justice, Jan. 31, 2006 1. John G. Roberts, Chief Justice, Sept. 29, 2005 (vote (vote 58-42) 78-22) Circuit Court Nominees 61. Raymond Kethledge, 6th Circuit, June 24, 31. Franklin van Antwerpen, 3rd Circuit, May 20, 2008 (voice vote) 2004 (vote 96-0)30. D. Michael Fisher, 3rd Circuit, 60. Helene N. White, 6th Circuit, June 24, 2008 Dec. 9, 2003 (voice vote) (vote 63-32) 29. Carlos Bea, 9th Circuit, Sept. 29, 2003 (vote 59. G. Steven Agee, 4th Circuit, May 20, 2008 86-0) (vote 96-0) 28. Steven Colloton, 8th Circuit, Sept. 4, 2003 58. Catharina Haynes, 5th Circuit, April 10, 2008 (vote 94-1) (unanimous consent) 27. Allyson K. Duncan, 4th Circuit, July 17, 2003 57. John Daniel Tinder, 7th Circuit, December 18, (vote 93-0) 2007(vote 93-0) 26. Richard Wesley, 2nd Circuit, June 11, 2003 56. -

Fire Alarms Or Smoke Detectors: the Role of Interest Groups in Confirmation of United States Courts of Appeals Judges

FIRE ALARMS OR SMOKE DETECTORS: THE ROLE OF INTEREST GROUPS IN CONFIRMATION OF UNITED STATES COURTS OF APPEALS JUDGES By DONALD E. CAMPBELL A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2016 © 2016 Donald E. Campbell To Ken and JJ ACKNOWLEDGMENTS It took Leo Tolstoy six years to write War and Peace. It has taken me twice that long to complete this dissertation, and I am certain I required much more support throughout the process than Tolstoy. I begin my acknowledgements with Dr. Marcus Hendershot. In short, this dissertation would not have been possible without Marc’s guidance, advice, and prodding. Every aspect of this dissertation has Marc’s imprint on it in some way. I cannot imagine the amount of time that he spent providing comments and suggestions. I will forever be in his debt and gratitude. I also want to thank the other members of my dissertation committee. Dr. Lawrence Dodd, the chair, has been a steadying force in my graduate school life since (literally) the first day I stepped in the door of Anderson Hall. His advice and encouragement will never be forgotten. The other members of my committee–Dr. Beth Rosenson, Dr. David Hedge, and Professor Danaya Wright (University of Florida School of Law)–have been more than understanding as the months dragged into years of getting the dissertation finalized. No one could ask for a better or more understanding dissertation committee. There are also several individuals outside of the University of Florida that I owe acknowledgements. -

Decision Making in Us Federal Specialized

THE CONSEQUENCES OF SPECIALIZATION: DECISION MAKING IN U.S. FEDERAL SPECIALIZED COURTS Ryan J. Williams A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Political Science in the College of Arts and Sciences. Chapel Hill 2019 Approved by: Kevin T. McGuire Isaac Unah Jason M. Roberts Virginia Gray Brett W. Curry © 2019 Ryan J. Williams ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Ryan J. Williams: The Consequences of Specialization: Decision Making in U.S. Federal Specialized Courts (Under the direction of Kevin T. McGuire) Political scientists have devoted little attention to the role of specialized courts in the United States federal and state judicial systems. At the federal level, theories of judicial decision making and institutional structures widely accepted in discussions of the U.S. Supreme Court and other generalist courts (the federal courts of appeals and district courts) have seen little examination in the context of specialized courts. In particular, scholars are just beginning to untangle the relationship between judicial expertise and decision making, as well as to understand how specialized courts interact with the bureaucratic agencies they review and the litigants who appear before them. In this dissertation, I examine the consequences of specialization in the federal judiciary. The first chapter introduces the landscape of existing federal specialized courts. The second chapter investigates the patterns of recent appointments to specialized courts, focusing specifically on how the qualifications of specialized court judges compare to those of generalists. The third chapter considers the role of expertise in a specialized court, the Court of Appeals for Veterans Claims, and argues that expertise enhances the ability for judges to apply their ideologies to complex, technical cases.