Memorandum Is Held by Steven G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2016 Summer Issue091216corrected.Indd

A PUBLICATION OF THE SILHA CENTER FOR THE STUDY OF MEDIA ETHICS AND LAW | SUMMER 2016 Gawker Shuts Down After Losing Its Initial Appeal of $140 Million Judgment in Privacy Case n Aug. 22, 2016, celebrity and media gossip to an investigation that the FBI conducted into an alleged website Gawker ceased operations after losing extortion attempt against Hogan by a third party. The records its initial appeal of a $140 million judgment in a were unsealed on March 18 while jurors were deliberating and March 2016 trial court battle with Terry Bollea, contained statements that Hogan, Clem, and Cole gave to the better known as professional wrestler Hulk FBI under oath that directly contradicted sworn deposition OHogan. The closure came after several tumultuous months for statements given to Gawker’s attorneys in 2015. In April 2016, Gawker’s parent company, Gawker Media, in which Florida Gawker fi led motions in the Florida state trial court asking state courts denied motions that the $140 million judgment Judge Campbell to overturn the jury’s verdict or to greatly be stayed pending appeal, bankruptcy fi lings, and revelations reduce the damages awarded to Hogan. (For more on the that a billionaire tech entrepreneur funded Hogan’s lawsuit as background of the legal dispute between Gawker and Hogan, part of a personal vendetta against the media company. The see “Gawker Faces $140 Million Judgment after Losing Privacy fi nal blow against Gawker came on August 16 after Gawker Case to Hulk Hogan” in the Winter/Spring 2016 issue of the Media was sold during a bankruptcy auction to Univision Silha Bulletin.) Communications Inc., which opted to close down the gossip website. -

Trump Judges: Even More Extreme Than Reagan and Bush Judges

Trump Judges: Even More Extreme Than Reagan and Bush Judges September 3, 2020 Executive Summary In June, President Donald Trump pledged to release a new short list of potential Supreme Court nominees by September 1, 2020, for his consideration should he be reelected in November. While Trump has not yet released such a list, it likely would include several people he has already picked for powerful lifetime seats on the federal courts of appeals. Trump appointees' records raise alarms about the extremism they would bring to the highest court in the United States – and the people he would put on the appellate bench if he is reelected to a second term. According to People For the American Way’s ongoing research, these judges (including those likely to be on Trump’s short list), have written or joined more than 100 opinions or dissents as of August 31 that are so far to the right that in nearly one out of every four cases we have reviewed, other Republican-appointed judges, including those on Trump’s previous Supreme Court short lists, have disagreed with them.1 Considering that every Republican president since Ronald Reagan has made a considerable effort to pick very conservative judges, the likelihood that Trump could elevate even more of his extreme judicial picks raises serious concerns. On issues including reproductive rights, voting rights, police violence, gun safety, consumer rights against corporations, and the environment, Trump judges have consistently sided with right-wing special interests over the American people – even measured against other Republican-appointed judges. Many of these cases concern majority rulings issued or joined by Trump judges. -

The Federalist Society for Law and Public Policy Studies 2009 Annual Report

The Federalist Society for Law and Public Policy Studies 2009 Annual Report “The Courts must declare the sense of the law; and if they should be disposed to exercise will instead of JUDGMENT, the consequences would be the substitution of their pleasure for that of the legislative body.” The Federalist 78 THE FEDERALIST SOCIETY aw schools and the legal profession are currently strongly dominated by a L form of orthodox liberal ideology which advocates a centralized and uniform society. While some members of the academic community have dissented from these views, by and large they are taught simultaneously with (and indeed as if they were) the law. The Federalist Society for Law and Public Policy Studies is a group of conservatives and libertarians interested in the current state of the legal order. It is founded on the principles that the state exists to preserve freedom, that the separation of governmental powers is central to our Constitution, and that it is emphatically the province and duty of the judiciary to say what the law is, not what it should be. The Society seeks both to promote an awareness of these principles and to further their application through its activities. This entails reordering priorities within the legal system to place a premium on individual liberty, traditional values, and the rule of law. It also requires restoring the recognition of the importance of these norms among lawyers, judges, law students and professors. In working to achieve these goals, the Society has created a conservative intellectual network that extends to all levels of the legal community. -

Hearing List March 2013

Supreme Court of the United States October Term, 2012 HEARING LIST For the Session Beginning March 18, 2013 (The Court convenes at 10 a.m.; afternoon arguments begin at 1 p.m.) Justices of the Supreme Court: Hon. Chief Justice John G. Roberts, Jr. Hon. Antonin Scalia Hon. Stephen G. Breyer Hon. Anthony M. Kennedy Hon. Samuel A. Alito, Jr. Hon. Clarence Thomas Hon. Sonia Sotomayor Hon. Ruth Bader Ginsburg Hon. Elena Kagan Officers of the Court: William K. Suter, Clerk Christine L. Fallon, Reporter of Decisions Pamela Talkin, Marshal Linda S. Maslow, Librarian HEARING LIST Monday, March 18, 2013 No. 12–71. Arizona, et al. v. The Inter Tribal Council of Arizona, Inc., et al. Certiorari to the C. A. 9th Circuit. For petitioners: Thomas C. Horne, Attorney General of Ari zona, Phoenix, Ariz. For respondents: Patricia Millett, Washington, D. C.; and Sri Srinivasan, Deputy Solicitor General, Department of Jus tice, Washington, D. C. (for United States, as amicus curiae.) (1 hour for argument.) No. 11–1518. Randy Curtis Bullock v. BankChampaign, N.A. Certiorari to the C. A. 11th Circuit. For petitioner: Thomas M. Byrne, Atlanta, Ga. For respondent: Bill D. Bensinger, Birmingham, Ala.; and Curtis E. Gannon, Assistant to the Solicitor General, De partment of Justice, Washington, D. C. (for United States, as amicus curiae.) (1 hour for argument.) Tuesday, March 19, 2013 No. 12–236. Kathleen Sebelius, Secretary of Health and Human Services v. Melissa Cloer. Certiorari to the C. A. Federal Circuit. For petitioner: Benjamin J. Horwich, Assistant to the Solici tor General, Department of Justice, Washington, D. -

Ted Cruz Promoted Himself and Conservative Causes As Texas’ Solicito

FORMER STATE SOLICITORS GENERAL AND OTHER STATE AG OFFICE ATTORNEYS WHO ARE ACTIVE JUDGES by Dan Schweitzer, Director and Chief Counsel, Center for Supreme Court Advocacy, National Association of Attorneys General March 18, 2021 Former State Solicitors General (and Deputy Solicitors General) Federal Courts of Appeals (11) Jeffrey Sutton – Sixth Circuit (Ohio SG) Timothy Tymkovich – Tenth Circuit (Colorado SG) Kevin Newsom – Eleventh Circuit (Alabama SG) Allison Eid – Tenth Circuit (Colorado SG) James Ho – Fifth Circuit (Texas SG) S. Kyle Duncan – Fifth Circuit (Louisiana SG) Andrew Oldham – Fifth Circuit (Texas Deputy SG) Britt Grant – Eleventh Circuit (Georgia SG) Eric Murphy – Sixth Circuit (Ohio SG) Lawrence VanDyke – Ninth Circuit (Montana and Nevada SG) Andrew Brasher – Eleventh Circuit (Alabama SG) State High Courts (6) Stephen McCullough – Virginia Supreme Court Nels Peterson – Georgia Supreme Court Gregory D’Auria – Connecticut Supreme Court John Lopez – Arizona Supreme Court Sarah Warren – Georgia Supreme Court Monica Marquez – Colorado Supreme Court (Deputy SG) State Intermediate Appellate Courts (8) Kent Cattani – Arizona Court of Appeals Karen King Mitchell – Missouri Court of Appeals Kent Wetherell – Florida Court of Appeals (Deputy SG) Scott Makar – Florida Court of Appeals Timothy Osterhaus – Florida Court of Appeals Peter Sacks – Massachusetts Court of Appeals Clyde Wadsworth – Hawaii Intermediate Court of Appeals Gordon Burns – California Court of Appeal (Deputy SG) Federal District Court (11) Gary Feinerman – Northern -

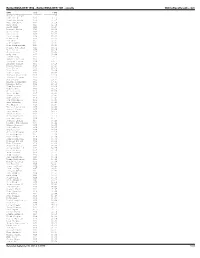

Bolderboulder 10K Results

BolderBOULDER 1994 - BolderBOULDER 10K - results OnlineRaceResults.com NAME DIV TIME ---------------------- ------- ----------- Matthew Lavigne 22 John Mirth M32 31:11 Jonathan Heese M36 31:37 Matt Schubert M24 31:58 Glen Mays M24 31:59 Brett Burt M28 32:07 Rodolfo Gomez M43 32:16 Chris Prior M34 32:21 Scott Kent M27 32:27 Darrin Rohr M29 32:30 Steve Roch M30 32:43 Rob Welo M30 32:43 John Ingram M22 32:44 John Pendergraft M27 32:45 Gerard Ostheimer M25 32:52 Mark Allen M36 32:56 Chris Severy M17 33:08 Andy Ames M31 33:09 Daniel King M34 33:10 Ignacio Morales M42 33:11 Richard Bishop M36 33:12 Brendan Reilly M34 33:16 Aaron Salomon M18 33:17 Dave Nelson M32 33:18 Rick Ames M33 33:26 Dennis Lima M32 33:33 Michael McCarrick M28 33:38 Michael Trunkes M31 33:43 Joe Sheely M35 33:44 Wilbur Ferdinand M32 33:47 Ricardo Rojas M42 33:50 Jeff Rosenow M37 33:52 Robert Love M30 33:54 Chris Borton M18 33:56 Marc Reider M27 34:01 Jason Porter M24 34:03 Sean Coster M18 34:04 Jon Schoenberg M31 34:05 Troy Pickett M31 34:06 Joe Wilson M18 34:07 Michael Sandrock M36 34:08 James Johnson M25 34:09 Bern Gever M34 34:11 Kevin Hilton M22 34:13 Chris Harrison M30 34:15 Lee Stringer M26 34:17 Douglas Hugill M33 34:20 Dominic Wyzomirski M34 34:22 Edward Boggess M36 34:23 John Wiberg M26 34:25 Andrew Crook M35 34:26 Chris Rodriguez M25 34:27 Allan Kupczak M33 34:28 Alex Furman M16 34:29 Daniel Hanewall M32 34:30 Mohamed Hajoui M32 34:32 Zeke Tiernan M18 34:33 Jason Nicholas M24 34:34 Jerry Duckworth M32 34:35 Parrick Aris M37 34:36 Thom Richman M39 34:37 Todd Reeser -

Meeting Hosts for June 2009 Chinese Student Program in Washington, D

US-ASIA INSTITUTE SZYMANSKI RULE OF LAW PROGRAM FOR CHINESE LAW STUDENTS Host List for Summer 2018 Program (June 25 – July 20, 2018) Washington, D.C. Participating Students: Ms. Floy Chen, Ms. Jennifer Hu, Mr. Henry Hu, Mr. Frank Jiang, Ms. Sally Zhang, & Ms. Rose Zhu (The following list was prepared for their benefit.) LEGISLATIVE BRANCH (CONGRESS) – THE SENATE • Sen. John Boozman of Arkansas, Chairman, Science & Space Subcommittee of the Commerce, Science, & Transportation (“Commerce”) Committee (also serves on the Committees for Agriculture, Nutrition, & Forestry (“Agriculture”); Environment & Public Works (“EPW”); and Veterans’ Affairs); • Sen. Tammy Duckworth of Illinois, Ranking Member, Environment & Public Works Subcommittee on Fisheries, Water, & Wildlife (also serves on the Commerce, Energy & Natural Resources, and Small Business Committees). • Sen. Richard Durbin of Illinois, Minority Whip (Sen. Durbin has served as the #2 Democratic leader in the Senate since January 2005; he also serves on the Appropriations, Judiciary, and Rules Committees). • Sen. Jeff Flake of Arizona, Member, Appropriations Committee (Sen. Flake previously served in the House); Staff: • Ms. Adrian Arnakis, Majority Deputy Staff Director, Commerce Committee (Sen. John Thune, Republican Conf. Chair); • Ms. Hazeen Ashby, Minority General Counsel, Commerce Committee (Sen. Bill Nelson of Florida); • Ms. Chanda Betourney, Minority Dep. Staff Director, Appropriations Committee (Sen. Patrick Leahy of Vermont); • Mr. Chris Bates, Chief Counsel, Judiciary Committee (Sen. Orrin Hatch / Chairman Chuck Grassley); • Mr. Walton Chaney, Legislative Aide, Sen. Cindy Hyde-Smith of Mississippi; • Mr. David Cleary, Majority Staff Director, Health/Educ/Labor (HELP) Committee (Sen. Lamar Alexander of Tenn.); • Mr. Mike Davis, Majority Chief Counsel for Nominations, Judiciary Committee (Sen. -

Judge Brett M. Kavanaugh: His Jurisprudence and Potential Impact on the Supreme Court

Judge Brett M. Kavanaugh: His Jurisprudence and Potential Impact on the Supreme Court Andrew Nolan, Coordinator Section Research Manager Caitlain Devereaux Lewis, Coordinator Legislative Attorney August 21, 2018 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R45293 SUMMARY R45293 Judge Brett M. Kavanaugh: His Jurisprudence August 21, 2018 and Potential Impact on the Supreme Court Andrew Nolan, On July 9, 2018, President Donald J. Trump announced the nomination of Judge Brett M. Coordinator Kavanaugh of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit (D.C. Circuit) to fill Section Research Manager retiring Justice Anthony M. Kennedy’s seat on the Supreme Court of the United States. [email protected] Nominated to the D.C. Circuit by President George W. Bush, Judge Kavanaugh has served on Caitlain Devereaux Lewis, that court for more than twelve years. In his role as a Circuit Judge, the nominee has authored Coordinator roughly three hundred opinions (including majority opinions, concurrences, and dissents) and Legislative Attorney adjudicated numerous high-profile cases concerning, among other things, the status of wartime [email protected] detainees held by the United States at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba; the constitutionality of the current structure of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau; the validity of rules issued by the For a copy of the full report, Environmental Protection Agency under the Clean Air Act; and the legality of the Federal please call 7-5700 or visit Communications Commission’s net neutrality rule. Since joining the D.C. Circuit, Judge www.crs.gov. Kavanaugh has also taught courses on the separation of powers, national security law, and constitutional interpretation at Harvard Law School, Yale Law School, and the Georgetown University Law Center. -

Senate Section (PDF929KB)

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 109 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 151 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, MAY 19, 2005 No. 67 Senate The Senate met at 9:30 a.m. and was ceed to executive session for the con- Yesterday, 21 Senators—evenly di- called to order by the President pro sideration of calendar No. 71, which the vided, I believe 11 Republicans and 10 tempore (Mr. STEVENS). clerk will report. Democrats—debated for over 10 hours The legislative clerk read the nomi- on the nomination of Priscilla Owen. PRAYER nation of Priscilla Richman Owen, of We will continue that debate—10 hours The Chaplain, Dr. Barry C. Black, of- Texas, to be United States Circuit yesterday—maybe 20 hours, maybe 30 fered the following prayer: Judge for the Fifth Circuit. hours, and we will take as long as it Let us pray. RECOGNITION OF THE MAJORITY LEADER takes for Senators to express their God of grace and glory, open our eyes The PRESIDENT pro tempore. The views on this qualified nominee. to the power You provide for all of our majority leader is recognized. But at some point that debate should challenges. Give us a glimpse of Your SCHEDULE end and there should be a vote. It ability to do what seems impossible, to Mr. FRIST. Mr. President, today we makes sense: up or down, ‘‘yes’’ or exceed what we can request or imagine. will resume executive session to con- ‘‘no,’’ confirm or reject; and then we Encourage us again with Your promise sider Priscilla Owen to be a U.S. -

Why Federal Courts Apply the Law of Nations Even Though It Is Not the Supreme Law of the Land

RESPONSE ARTICLE Why Federal Courts Apply the Law of Nations Even Though it is Not the Supreme Law of the Land ANTHONY J. BELLIA JR.* & BRADFORD R. CLARK** TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION . 1916 I. THE LAW OF NATIONS AND THE UNITED STATES CONSTITUTION. 1918 II. THE STATUS OF THE LAW OF NATIONS UNDER THE CONSTITUTION . 1926 A. THE LAW OF NATIONS AS SUPREME FEDERAL LAW . 1927 B. THE LAW OF NATIONS AND THE CONSTITUTIONAL TEXT. 1931 III. THE LAW OF NATIONS AND THE RECOGNITION POWER. 1935 A. THE RECOGNITION POWER IN SUPREME COURT DECISIONS . 1936 1. The Law of Nations as General Law . 1937 2. The Recognition Power in the Twentieth Century . 1939 B. THE LAW OF NATIONS, THE ALLOCATION OF POWERS, AND EARLY CASES . ................. ............. 1942 1. Recognition and the Allocation of Powers . 1944 a. Recognition and the Law of Nations . 1945 b. Recognition and Other Foreign Relations Powers . 1946 c. Recognition Under the Law of Nations . 1947 2. The Law of Nations in Early Supreme Court Cases . 1950 CONCLUSION ...................................................... 1960 * O'Toole Professor of Constitutional Law, Notre Dame Law School. © 2018, Anthony J. Bellia Jr. & Bradford R. Clark. We thank Tricia Bellia, Val Clark, and John Manning for helpful comments and suggestions, and all of the participants for their contributions to this symposium. We also thank The Georgetown Law Journal for organizing and publishing this symposium. ** William Cranch Research Professor of Law, George Washington University Law School. 1915 1916 THE GEORGETOWN LAW -

Federal Judiciary Tracker

Federal Judiciary Tracker An up-to-date look at the federal judiciary and the status of President Trump’s judicial nominations October 23, 2020 Trump has had 225 federal judges confirmed while 25 seats remain vacant without a nominee Status of key positions 25 President Trump inherited 108 federal requiring Senate 41 judge vacancies confirmation As of October 22, 2020: ■ No nominee ■ Awaiting confirmation 157 judiciary positions have opened up ■ Confirmed during Trump’s presidency and either remain vacant or have been filled Total: 265 potential Trump nominations 225 Source: United States Courts Trump has had more circuit judges confirmed than the average of recent presidents at this point Number of Federal Judges Nominated and Confirmed Trump 161 53 2 ■ District court judge ■ Circuit court judge ■ Supreme Court judge Obama 128 30 2 Source: Federal Judicial Center Bush 165 35 Clinton 169 30 2 HW Bush 148 42 2 In three and a half years, Trump has confirmed a higher number of circuit judges as prior presidents in four years Number of Federal Judges Nominated and Confirmed Trump 161 53 2 ■ District court judge ■ Circuit court judge Obama 141 30 2 ■ Supreme Court judge Source: Federal Judicial Center Bush 168 35 Clinton 169 30 2 HW Bush 148 42 2 An overview of the Article III courts US District Courts US Court of Appeals Supreme Court Organization: Organization: Organization: • The nation is split into 94 • Federal judicial districts • The Supreme Court is the federal judicial districts are organized into 12 highest court in the US • The District of Columbia circuits, which each have a • There are nine justices on and four US territories court of appeals. -

Georgetownfeature / a Changing World Law Spring/Summer 2017

GEORGETOWNFEATURE / A CHANGING WORLD LAW SPRING/SUMMER 2017 WORLD A CHANGING 5 / News: The Highlights 22 / Feature: Georgetown Law Responds to a Changing World 44 / Feature: Tech at Georgetown Law 60 / Campus: Our Faculty, Staff and Students 75 / Alumni: Leading the Way i Georgetown Law GEORGETOWN LAW Spring/Summer 2017 ANN W. PARKS Editor BRENT FUTRELL Director of Design INES HILDE Senior Designer MIMI KOUMANELIS Executive Director of Communications TANYA WEINBERG Director of Media Relations and Deputy Director of Communications RICHARD SIMON Director of Web Communications JACLYN DIAZ Communications and Social Media Manager BEN PURSE Senior Video Producer JERRY COOPER Communications Associate MATTHEW F. CALISE Director of Alumni Affairs JANE AIKEN Vice President for Strategic Development and External Affairs WILLIAM M. TREANOR Dean of the Law Center Executive Vice President, Law Center Affairs Cover design: INES HILDE Contact: Editor, Georgetown Law Georgetown University Law Center 600 New Jersey Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20001 [email protected] Address changes/additions/deletions: 202-687-1994 or e-mail [email protected] Georgetown Law magazine is on the Law Center’s website at www.law.georgetown.edu Copyright © 2017, Georgetown University Law Center. All rights reserved. “Whatever your passion is, pursue that.” Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg 2017 Spring/Summer 1 INSIDE / 10 / 14 Custodians of the Constitution: A Conversation with Khizr Khan IIEL Celebrates Black History Month As Professor Neal Katyal notes, it often takes an immigrant Our Institute of International Economic Law welcomes new to teach us about America. members of the Congressional Black Caucus. / 16 / 18 Making History: Avril Haines (L’01) Supreme Court Win Haines, a 2017 Alumnae Award winner, talks about her Professor Brian Wolfman, students in his new Appellate government service in the national security arena.