A Study of the Impact of the Old Georgetown Act

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Georgetown University and the Master of Professional Studies Program

School of Continuing Studies Graduate Student Handbook Liberal Studies & Professional Studies Academic Rules and Regulations 2012-2013 Table of Contents WELCOME ................................................................................................................................................. 8 UNIVERSITY MISSION STATEMENT ....................................................................................................................... 8 SCHOOL MISSION STATEMENT .............................................................................................................................. 8 HISTORY OF THE SCHOOL OF CONTINUING STUDIES ......................................................................................... 8 ACCREDITATION & CERTIFICATION INFORMATION ........................................................................................... 9 DISCLAIMER, WEBSITE, AND UPDATE INFORMATION ....................................................................................... 9 CONTACTING US .................................................................................................................................. 11 IMPORTANT WEBSITES ........................................................................................................................................ 11 Georgetown University ...................................................................................................................................... 11 School of Continuing Studies .......................................................................................................................... -

The Institutes

Summer Programs for High School Students 2015 Welcome Packet The Institutes June 14-June 21 June 21-June 28 June 28-July 5 July 5-July 12 July 12-July 19 July 19-July 26 July 26-August 2 Table of Contents Welcome to Summer at Georgetown 3 Your Pre-Arrival Checklist 4 Institute Program Calendar 5 Preparing for Your Summer at Georgetown 6 Enroll in NetID Password Station 6 Register for Your Institute(s) 6 Apply for Your GOCard 7 Submit Your Campus Life Forms 7 Learning the Georgetown Systems 8 During Your Program 10 Residential Living 13 On Campus Resources 15 Check-In Day 16 Campus Map 18 Check-Out 19 Georgetown University Summer Programs for High School Students 3307 M St. NW, Suite 202 Washington, D.C. 20057 Phone: 202-687-7087 Email: [email protected] 2 WELCOME TO SUMMER AT GEORGETOWN! CONGRATULATIONS! Congratulations on your acceptance to the Institute program at Georgetown University’s Summer Pro- grams for High School Students! We hope you are looking forward to joining us on the Hilltop soon. Please make sure you take advantage of the resources offered by Georgetown University! The Summer and Special Programs office, a part of the School of Continuing Studies at Georgetown Universi- ty, provides world renowned summer programs that attract students from around the United States of America and the world. As you prepare for your arrival on Georgetown’s campus, our staff is available to provide you with academic advising and to help you plan and prepare for your college experience at Georgetown. -

SPRING 1966 GEORGETOWN Is Published in the Fall, Winter, and Spring by the Georgetown University Alumni Association, 3604 0 Street, Northwest, Washington, D

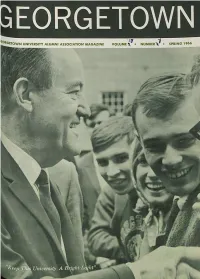

SPRING 1966 GEORGETOWN is published in the Fall, Winter, and Spring by the Georgetown University Alumni Association, 3604 0 Street, Northwest, Washington, D. C. 20007 Officers of the Georgetown University Alumni Association President Eugene L. Stewart, '48, '51 Vice-Presidents CoUege, David G. Burton, '56 Graduate School, Dr. Hartley W. Howard, '40 School of Medicine, Dr. Charles Keegan, '47 School of Law, Robert A. Marmet, '51 School of Dentistry, Dr. Anthony Tylenda, '55 School of Nursing, Miss Mary Virginia Ruth, '53 School of Foreign Service, Harry J. Smith, Jr., '51 School of Business Administration, Richard P. Houlihan, '54 Institute of Languages and Linguistics, Mrs. Diana Hopkins Baxter, '54 Recording Secretary Miss Rosalia Louise Dumm, '48 Treasurer Louis B. Fine, '25 The Faculty Representative to the Alumni Association Reverend Anthony J . Zeits, S.J., '43 The Vice-President of the University for Alumni Affairs and Executive Secretary of the Association Bernard A. Carter, '49 Acting Editor contents Dr. Riley Hughes Designer Robert L. Kocher, Sr. Photography Bob Young " Keep This University A Bright Light' ' Page 1 A Year of Tradition, Tribute, Transition Page 6 GEORGETOWN Georgetown's Medical School: A Center For Service Page 18 The cover for this issue shows the Honorable Hubert H. Humphrey, Vice On Our Campus Page 23 President of the United States, being Letter to the Alumni Page 26 greeted by students in the Yard before 1966 Official Alumni historic Old North preceding his ad Association Ballot Page 27 dress at the Founder's Day Luncheon. Book Review Page 28 Our Alumni Correspondents Page 29 "Keep This University A Bright Light" The hard facts of future needs provided a con the great documents of our history," Vice President text of urgency and promise for the pleasant recol Humphrey told the over six hundred guests at the lection of past achievements during the Founder's Founder's Day Luncheon in New South Cafeteria. -

Welcome Back Alumni

Welcome Back Alumni Vol. LI, No.9 GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY, WASHINGTON, D.C. Thursday, November 16, 1967 I Klein's Open House Plan I , " cd Draws Student Rejection The Walsh Area Student Coun "1. The doors of all student "3. The House Councils will be cil, the Yard Council, and the Har rooms in a particular residence responsible for the proper running bin, New South, and Copley House hall must remain completely open of the Open Houses. Some of the for the duration of the Open House housemasters and resident a:;sist Councils rejected the provisions of that residence hall. ants will be in attendance to assist promulgated for Homecoming open "2. The hours of the Open the House Councils with proced house periods by Mr. Edward R. Houses will be as follows: Copley ural matters." Klein, Jr., dean of men. Hall: 4:00 p.m. to 6:00 p.m., Har Before reading his statement, ''7 - bin Hall: 12:30 p.rn. to 1:30 p.m., Mr. Klein announced that he The councils condemned the New South: 12:30 p.m. to 1:30 p.m. (Continued on Page 15) '~!"'>I' ::'.• ,,,-: condition that the door of every .', student room must remain open .... " .. during the periods. Harbin and ., .. ',. New South residents charged that an injustice had been done them :~:~ /":'~> 4" ,;:<',';.:,: ~:.\' 'f~::_~,!:?;:;:'~-;;-:~,:;·;~~'~.>~;;~~:~,jii;; --~:.!:~:~>:, ':'-: GU Policy Directed in, Mr. Klein's assignment of Homecoming '67 cheers two teams. Pictured above is Mike Agee's shorter hours for the i l' 0 pen squad, which will meet Fordham on Saturday. Fordham will also houses than for Copley's. -

Summer Programs for High School Students

Summer Programs for summer.georgetown.edu/hoyas2015 High School Students Summer Programs for summer.georgetown.edu/hoyas2015 High School Students SUMMER AT GEORGETOWN SUMMER PROGRAMS FOR HIGH SCHOOL STUDENTS INTRODUCTION ........................................................................... 2 SUMMER PROGRAMS .................................................................... 3 Institutes & Fundamentals ........................................................ 3 College Prep ............................................................................ 4 Summer College Courses & Summer Honors Intensive ................... 5 PROGRAM CALENDAR ................................................................... 6 SUBJECT AREAS ........................................................................... 8 Arts & Humanities .................................................................... 8 Business ................................................................................10 Government ...........................................................................11 Law .......................................................................................13 Medicine & Science .................................................................14 CAMPUS LIFE ..............................................................................16 APPLICATION INFORMATION & CHECKLIST .....................................18 FOR PARENTS .............................................................................20 High school students who participated -

Doctor of Liberal Studies, Student Handbook

Doctor of Liberal Studies, Student Handbook Academic Rules and Regulations 2017 - 2018 Table of Contents WELCOME..................................................................................................................................... 5 UNIVERSITY MISSION STATEMENT ............................................................................................................. 5 SCHOOL MISSION STATEMENT ................................................................................................................... 5 HISTORY OF THE SCHOOL OF CONTINUING STUDIES ................................................................................... 5 JESUIT VALUES AT GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY: THE SPIRIT OF GEORGETOWN ......................................... 6 ACCREDITATION & CERTIFICATION INFORMATION .................................................................................... 8 DISCLAIMER, WEBSITE, AND UPDATE INFORMATION ................................................................................. 8 OWNER OF INSTITUTION ............................................................................................................................. 9 OFFICE OF ACADEMIC AFFAIRS & COMPLIANCE ........................................................................................ 9 UNIVERSITY POLICIES ............................................................................................................ 10 OFFICE OF BILLING AND PAYMENT SERVICES ...........................................................................................10 -

University Security Officers Charged with 'Malpractice' Charges of "Illegal Search and and Trunks of Vehicles Towed on Ciety, Pierce O'donnell (Law '72)

Vol. LII, No. 10 GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY, WASHINGTON, D.C. Thursday, November 13, 1969 University Security Officers Charged With 'Malpractice' Charges of "illegal search and and trunks of vehicles towed on ciety, Pierce O'Donnell (Law '72). seizure" have been leveled against Georgetown premises. In addition, O'Donnell stated the University's traffic department, The charges were advanced by that the articles obtained in alleging malpractice for searching the executive director of the searching automobiles are inven all unlocked glove compartments Georgetown Legal Assistance So- toried. Items considered "sus picious or potentially incriminat ing" are forwarded to Capt. Wil liam Fotta, who heads the security police force on campus. Fotta then Report Overruled; determines the disposition of the articles. Sgt. John Barr, coordinator of Gym To Be Used the traffic department, and Capt. Fotta confirmed the existence of McDonough Gymnasium will The marshalling force from the the searching practices. serve as a housing facility for 650 mobilization will be augmented by O'Donnell, in a letter sent to AYS students from different East the leaders of the student govern Dayton P. Morgan, University Coast universities who will par ment, O'Keefe said. vice president for business and fi ticipate in National Mobilization O'Keefe also noted that each nance, under whose jurisdiction Committee activities today, tomor residence hall has aetermined its the traffic department functions, ;S. own policy concerning the hous stated that his investigation into row, and Saturday. :LEASE This decision was announced by ing of students for the weekend. the standing policy of the traffic the Rev. Robert J. -

1980-04-01.Pdf (3.1MB)

• News 3 Nothing in the least interesting, infor Cry Rape! mative, or that hasn't already been covered in the HOYA We have been raped. Arts 9 The Voice is very much like a woman: proud, sen A review of a play that closed two sitive, very aware of it's rightful place in the world. We weeks ago; a pretentious and verbose critique of an album that no one is go even run on our own cycle. But, unlike a woman, we ing to but anyway have a sense of honor, and that sense of honor has been . sullied by the shocking act that resulted in the theft of Cover 10 this newspaper, whose monetary value is approximately A last-ditch attempt to get people to get people to pick up our newsmagazine 1200 dollars. But the issue is not money, but rape. We in spite of the cliche-ridden prose and demand satisfaction, and, aga,in like a woman, we pro non-sequitor commentary. Behind bably won't get it. Sports II The facts in the case are simple. We work hard all Now that the basketball season is week gathering the news, sports, and features that you over, pretty lean pickings. Reports on see tastefully presented in our pages. Monday night we minor sports that get almost no funding theLinM and lose all the time. take what we in the newspaper business call "flats", worth around 1200 dollars, to our printers, the Nor C.S. Lewis once said that thern Virginia Sun. Sometime between nine and nine "You always hurt the one you eleven, the flats, (worth over a thousand dollars), were Board 0/ Worth love", and he almost certainly agree that, at least at Georgetown found to be missing, searched for, declared officially Mark Whimp. -

H Oya B Asketball G Eorgetow N Staff Team R Eview Tradition R Ecords O Pponents G U Athletics M Edia

9 2 2006-07 GEORGETOWN MEN’S BASKETBALL HoyaHoya BasketballBasketball GGeorgetowneorgetown StaffStaff TeamTeam ReviewReview Tradition Records Opponents GU Athletics Media Tradition Staff Staff Georgetown Basketball Hoya Team Team Review Tradition Media Athletics GU Opponents Records 2006-072 0 0 6 - 0 7 GEORGETOWNG E O R G E T O W N MEN’SM E N ’ S BASKETBALLB A S K E T B A L L 9 3 Basketball Hoya Georgetown Staff Hoya Tradition In its fi rst 100 years, the Georgetown Basketball program has been highlighted by rich tradition... Historical records show us the accomplishments of future Congressman Henry Hyde and his team in the 1940s. Professional achievement tells us of the academic rigor and athletic pursuits of the 1960s that helped shape Paul Tagliabue, former Commissioner of the NFL. Trophies, awards and championships are evidence of the success John Thompson Jr. compiled in the 1970s, 80s and 90s. It is the total combination: academic and athletic excellence, focus, dedication and hard work instilled in Hoya teams throughout the last century that built men who would not only conquer the basketball court, but serve their communities. This is the tradition of Georgetown University and its basketball program. Team Team Review Review Tradition 1942 Buddy O’Grady, Al Lujack and Don Records Opponents Athletics GU Media 1907 1919 Bill Martin graduate and are selected by the Bornheimer Georgetown beats Virginia, 22-11, in the Led by Fred Fees and Andrew Zazzali, National Basketball Association. They are fi rst intercollegiate basketball game in the Hilltop basketball team compiles the fi rst of 51 Hoyas to play in the NBA. -

Georgetown University Ryan A.Sakamoto Washington, D.C

2007-08 SCHEDULE MEN’S TENNIS Jan. 18 VCU 4+1 Tournament & .................................all day Jan. 25 at Old Dominion ............................................... 1 p.m. Jan. 26 at Navy .................................................................. noon Feb. 1 at Penn ............................................................... 2 p.m. Feb. 2 at Maryland .......................................................... noon Feb. 9 at DePaul * .......................................................... noon Feb. 10 at Marquette * .................................................10 a.m. Feb. 23 YALE # ...................................................5:30 p.m. Mar. 1 BINGHAMTON # ................................5:30 p.m. Mar. 3 at Barry ................................................................. noon Mar. 4 at Lynn ..............................................................10 a.m. Mar. 7 at Florida Atlantic ............................................... noon Mar. 15 ST. JOHN’S * ................................................ noon Mar. 16 BOSTON COLLEGE ................................11 a.m. Kevin Mar. 20 at Richmond ................................................2:30 p.m. WALSHWALSH Mar. 26 UMBC ..........................................................2 p.m. Mar. 28 at George Washington ................................... 2 p.m. Apr. 4 VILLANOVA * .............................................1 p.m. Apr. 5 CONNECTICUT * ........................................ noon Liz Apr. 10 at James Madison ........................................... -

V~Vid. Social Sche

\I Vol. XLW. No. '\}g, I g GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY. WASHINGTON. D. C. Thursday. March 5. 1964 V~vid. Social Sche£!uJe HOYAMovesWithdrawal Ihghhgh~~TO!:?!ent VISIt At Picketed Council S nod The 1964 College Parents' Weekend festivities begin Y tomorrow night with registration of parents in New South Before a capacity crowd in Faculty Lounge. Registration will continue Saturday morn- Copley Lounge last Sunday ing. With the completion of registration, sample classes will night, The HOYA announced be conducted in history, philosophy, English and science. By its intentions to withdraw its attending mock classes, the parents will become acquainted representation from the Col- with academic standards ex- lege Student Council. pected of their sons. John Glavin. Associate Editor of the Campus newspaper and its cur- Politiesl Msneuverings The traditional Parents' rent delegate to the Council. pre- Weekend cocktail party is sented the decision of the 1964 Higllligllt Performsnee next on the agenda. The editorial board to resign its seat ·1 from the student body representa- cock tal party will commence tive organ at the Council's weekly Of/Re'S Fsvoretl "4" in McDonough Gymnasium imme- meeting. This past week the Inter diately after the sample classes. Glavin. a senior in the College national Relations Club sent At this event parents will have a and former Editor-in-Chief of The chance to speak with their son's HOYA, specified the reasons for a four-man delegation to the teachers and other faculty mem- the Board's decision. He said that Little United Nations As bers of the College. IN THE YARD •.• Ken Atchity withdraws HOYA from Stuoont. -

Dance Boat Ride Head Fr. Collins Reveals Ne", Officers Elected;

Yol. XLIV, No. 23 GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY, WASHINGTON, D. C. Thursday, May 9, 1963 ,: Dance Boat Ride Head Fr. Collins Reveals Ne", Officers Elected; ~ 1.. A '1 sew 'k d New Building Plans StU et Th '4 nnua prIng ee en For Future Dorms uppor nl y erne At 1 :30 last Thursday af ternoon Father T. Byron Col lins, S.J., made public the . ,. designs for two new Campus dormitories. The dormitories are a part of a long-promised building program. The plans call for a men's dorm, ." ·,·ccommodating four hundred and " _ ~rty Georgetown gentlemen, to J~ be constructed on the Lower Field .' .. between New North and the Jesuit Cemetery, and for a women's dorm , accommodating 336 Georgetown ',. ladies, adjacent to St. Mary's. The planned date for completion of these buildings is autumn of 1964. Groundbreaking will begin . ... early this fall. { WHEEL AND DEAL . • appears to be the aim of the Spring From the Terrace NEW DEAL . The victors of the class contests for the pres idency and representation are, bottom row, left to right: Ed Shaw, Weekend committee. Bottom row, left to right: Mike Silane, .Jim The men's dorm will be con Bryan, Gene Bennett, .Joe McGowan. Top, left to right: .Jack Mitchell, Dave Clossey, and Brendan Sullivan. Top: George Thibault, .Jack structed on a terrace, cutting slight Callagy, and Barry Smyth. Ed Coletti, Charles Carozza, Tom Capotosta, .John Dono.van. ly into the adjoining hillside. Under by Steve Hesse the terrace, hidden from public by Herb Kenny view will be a maintenance garage.