Sumatran Orangutans and a Yellow-Cheeked Crested Gibbon Know What Is Where

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

10 Sota3 Chapter 7 REV11

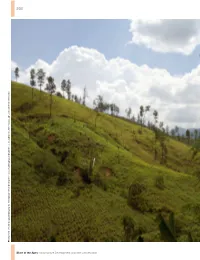

200 Until recently, quantifying rates of tropical forest destruction was challenging and laborious. © Jabruson 2017 (www.jabruson.photoshelter.com) forest quantifying rates of tropical Until recently, Photo: State of the Apes Infrastructure Development and Ape Conservation 201 CHAPTER 7 Mapping Change in Ape Habitats: Forest Status, Loss, Protection and Future Risk Introduction This chapter examines the status of forested habitats used by apes, charismatic species that are almost exclusively forest-dependent. With one exception, the eastern hoolock, all ape species and their subspecies are classi- fied as endangered or critically endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) (IUCN, 2016c). Since apes require access to forested or wooded land- scapes, habitat loss represents a major cause of population decline, as does hunting in these settings (Geissmann, 2007; Hickey et al., 2013; Plumptre et al., 2016b; Stokes et al., 2010; Wich et al., 2008). Until recently, quantifying rates of trop- ical forest destruction was challenging and laborious, requiring advanced technical Chapter 7 Status of Apes 202 skills and the analysis of hundreds of satel- for all ape subspecies (Geissmann, 2007; lite images at a time (Gaveau, Wandono Tranquilli et al., 2012; Wich et al., 2008). and Setiabudi, 2007; LaPorte et al., 2007). In addition, the chapter projects future A new platform, Global Forest Watch habitat loss rates for each subspecies and (GFW), has revolutionized the use of satel- uses these results as one measure of threat lite imagery, enabling the first in-depth to their long-term survival. GFW’s new analysis of changes in forest availability in online forest monitoring and alert system, the ranges of 22 great ape and gibbon spe- entitled Global Land Analysis and Dis- cies, totaling 38 subspecies (GFW, 2014; covery (GLAD) alerts, combines cutting- Hansen et al., 2013; IUCN, 2016c; Max Planck edge algorithms, satellite technology and Insti tute, n.d.-b). -

Gibbon Classification : the Issue of Species and Subspecies

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1988 Gibbon classification : the issue of species and subspecies Erin Lee Osterud Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Biological and Physical Anthropology Commons, and the Genetics and Genomics Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Osterud, Erin Lee, "Gibbon classification : the issue of species and subspecies" (1988). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 3925. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.5809 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Erin Lee Osterud for the Master of Arts in Anthropology presented July 18, 1988. Title: Gibbon Classification: The Issue of Species and Subspecies. APPROVED BY MEM~ OF THE THESIS COMMITTEE: Marc R. Feldesman, Chairman Gibbon classification at the species and subspecies levels has been hotly debated for the last 200 years. This thesis explores the reasons for this debate. Authorities agree that siamang, concolor, kloss and hoolock are species, while there is complete lack of agreement on lar, agile, moloch, Mueller's and pileated. The disagreement results from the use and emphasis of different character traits, and from debate on the occurrence and importance of gene flow. GIBBON CLASSIFICATION: THE ISSUE OF SPECIES AND SUBSPECIES by ERIN LEE OSTERUD A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in ANTHROPOLOGY Portland State University 1989 TO THE OFFICE OF GRADUATE STUDIES: The members of the Committee approve the thesis of Erin Lee Osterud presented July 18, 1988. -

7 Gibbon Song and Human Music from An

Gibbon Song and Human Music from an 7 Evolutionary Perspective Thomas Geissmann Abstract Gibbons (Hylobates spp.) produce loud and long song bouts that are mostly exhibited by mated pairs. Typically, mates combine their partly sex-specific repertoire in relatively rigid, precisely timed, and complex vocal interactions to produce well-patterned duets. A cross-species comparison reveals that singing behavior evolved several times independently in the order of primates. Most likely, loud calls were the substrate from which singing evolved in each line. Structural and behavioral similarities suggest that, of all vocalizations produced by nonhuman primates, loud calls of Old World monkeys and apes are the most likely candidates for models of a precursor of human singing and, thus, human music. Sad the calls of the gibbons at the three gorges of Pa-tung; After three calls in the night, tears wet the [traveler's] dress. (Chinese song, 4th century, cited in Van Gulik 1967, p. 46). Of the gibbons or lesser apes, Owen (1868) wrote: “... they alone, of brute Mammals, may be said to sing.” Although a few other mammals are known to produce songlike vocalizations, gibbons are among the few mammals whose vocalizations elicit an emotional response from human listeners, as documented in the epigraph. The interesting questions, when comparing gibbon and human singing, are: do similarities between gibbon and human singing help us to reconstruct the evolution of human music (especially singing)? and are these similarities pure coincidence, analogous features developed through convergent evolution under similar selective pressures, or the result of evolution from common ancestral characteristics? To my knowledge, these questions have never been seriously assessed. -

The Ecology and Conservation of the Critically Endangered Cross River Gorilla in Cameroon © 2012

The Ecology and Conservation of the Critically Endangered Cross River Gorilla in Cameroon By Sarah Cahill Sawyer A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Environmental Science, Policy, and Management in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Justin Brashares, Chair Professor Steve Beissinger Professor William Lidicker Fall 2012 The Ecology and Conservation of the Critically Endangered Cross River Gorilla in Cameroon © 2012 By Sarah Cahill Sawyer ABSTRACT: The Ecology and Conservation of the Critically Endangered Cross River Gorilla in Cameroon By Sarah Cahill Sawyer Doctor of Philosophy in Environmental Science, Policy, and Management University of California, Berkeley Professor Justin Brashares, Chair The Cross River gorilla (Gorilla gorilla diehli; hereafter: CRG) is one of the world’s most endangered and least studied primates. CRG exist only in a patchy distribution in the southern portion of the Cameroon-Nigeria border region and may have as few as 300 individuals remaining, divided into 14 fragmented subpopulations. Though Western gorillas (Gorilla gorilla spp) probably once inhabited much greater ranges throughout West Africa, today CRG represent the most northern and western distribution of all gorillas and are isolated from Western lowland gorilla populations by more than 250 km. CRG have proved challenging to study and protect, and many of the remaining subpopulations currently exist outside of protected areas. Very little is known about where the various subpopulations range on the landscape or why they occur in a patchy distribution within seemingly intact habitat. Active efforts are currently underway to identify critical habitat for landscape conservation efforts to protect the CRG in this biodiversity hotspot but, to date, a lack of understanding of the relationship between CRG ecology and available habitat has hampered conservation endeavors. -

An Assessment of Trade in Gibbons and Orang-Utans in Sumatra, Indoesia

AN ASSESSMENT OF TRADE IN GIBBONS AND ORANG-UTANS IN SUMATRA, INDONESIA VINCENT NIJMAN A TRAFFIC SOUTHEAST ASIA REPORT Published by TRAFFIC Southeast Asia, Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia © 2009 TRAFFIC Southeast Asia All rights reserved. All material appearing in this publication is copyrighted and may be reproduced with permission. Any reproduction in full or in part of this publication must credit TRAFFIC Southeast Asia as the copyright owner. The views of the authors expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of the TRAFFIC Network, WWF or IUCN. The designations of geographical entities in this publication, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of TRAFFIC or its supporting organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The TRAFFIC symbol copyright and Registered Trademark ownership is held by WWF. TRAFFIC is a joint programme of WWF and IUCN. Layout by Noorainie Awang Anak, TRAFFIC Southeast Asia Suggested citation: Vincent Nijman (2009). An assessment of trade in gibbons and orang-utans in Sumatra, Indonesia TRAFFIC Southeast Asia, Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia ISBN 9789833393244 Cover: A Sumatran Orang-utan, confiscated in Aceh, stares through the bars of its cage Photograph credit: Chris R. Shepherd/TRAFFIC Southeast Asia An assessment of trade in gibbons and orang-utans in Sumatra, Indonesia Vincent Nijman Cho-fui Yang Martinez -

Traffic Southeast Asia Report

HANGING IN THE BALANCE: AN ASSESSMENT OF TRADE IN ORANG-UTANS AND GIBBONS ON KALIMANTAN,INDONESIA VINCENT NIJMAN A TRAFFIC SOUTHEAST ASIA REPORT TRAFFIC SOUTHEAST ASIA Published by TRAFFIC Southeast Asia, Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia © 2005 TRAFFIC Southeast Asia All rights reserved. All material appearing in this publication is copyrighted and may be produced with permission. Any reproduction in full or in part of this publication must credit TRAFFIC Southeast Asia as the copyright owner. The views of the authors expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of the TRAFFIC Network, WWF or IUCN. The designations of geographical entities in this publication, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of TRAFFIC or its supporting organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The TRAFFIC symbol copyright and Registered Trademark ownership is held by WWF, TRAFFIC is a joint programme of WWF and IUCN. Layout by Noorainie Awang Anak, TRAFFIC Southeast Asia Suggested citation: Vincent Nijman (2005), Hanging in the Balance: An Assessment of trade in Orang-utans and Gibbons in Kalimantan, Indonesia TRAFFIC Southeast Asia ISBN 983-3393-03-9 Photograph credit: Pet Müller’s Gibbon Hylobates muelleri, West Kalimantan, Indonesia (Ian M. Hilman/Yayasan Titian) Hanging in the Balance: An Assessment of Trade in Orang-utans and Gibbons in Kalimantan, Indonesia HANGING IN THE BALANCE: An assessment of trade in orang-utans and gibbons in Kalimantan, Indonesia Vincent Nijman August 2005 Yuyun Kurniawan/Yayasan Titian Kurniawan/Yayasan Yuyun Credit: Credit: Orang-utan and macaque skulls used for decoration in Central Kalimantan. -

CHIMPANZEE (Pan Troglodytes ) CARE MANUAL

CHIMPANZEE (Pan troglodytes) CARE MANUAL CREATED BY THE AZA Chimpanzee Species Survival Plan® IN ASSOCIATION WITH THE AZA Ape Taxon Advisory Group Chimpanzee (Pan Troglodytes) Care Manual Chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) Care Manual Published by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums in association with the AZA Animal Welfare Committee Formal Citation: AZA Ape TAG 2010. Chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) Care Manual. Association of Zoos and Aquariums, Silver Spring, MD. Original Completion Date: December 8, 2009 Authors and Significant Contributors: Steve Ross, Ph.D. Lincoln Park Zoo Jennie McNary, Los Angeles Zoo See Appendix F for a full list of contributors and reviewers from the AZA Chimpanzee SSP. Reviewers: Linda Brent, Ph.D., Chimp Haven, Inc. Maria Finnigan, Perth Zoo, ASMP Chimpanzee Coordinator Steve Ross, Ph.D., Lincoln Park Zoo Candice Dorsey, Ph.D., AZA Director, Animal Conservation Debborah Colbert, Ph.D., AZA VP, Animal Conservation Paul Boyle, Ph.D., AZA Sr. VP Conservation and Education See Appendix F for a full list of contributors and reviewers from the AZA Chimpanzee SSP. Chimpanzee Care Manual Project Consultant: Joseph C.E. Barber, Ph.D. AZA Staff Editors: Candice Dorsey, Ph.D., Director, Animal Conservation Cover Photo Credits: Steve Ross Disclaimer: This manual presents a compilation of knowledge provided by recognized animal experts based on the current science, practice, and technology of animal management. The manual assembles basic requirements, best practices, and animal care recommendations to maximize capacity for excellence in animal care and welfare. The manual should be considered a work in progress, since practices continue to evolve through advances in scientific knowledge. The use of information within this manual should be in accordance with all local, state, and federal laws and regulations concerning the care of animals. -

Wildlife Without Borders - Great Ape Conservation Fund

Wildlife Without Borders - Great Ape Conservation Fund In 2012, the USFWS awarded 47 new grants from the Great Ape Conservation Fund totaling $3,333,562.68 which was matched by $4,947,144 in leveraged funds. Field projects in 17 countries (in alphabetical order below) will be supported. AFRICA In 2012, the USFWS awarded 25 new grants in eight African countries totaling $2,168,307.58 in USFWS funding which was matched by $3,844,684 in leveraged funds. In addition to one project that involves multiple countries. CAMEROON Capacity building for Great Ape Conservation and Natural Resource Management across the Deng Deng National Park Landscape, Cameroon. GA-0900 Wildlife Conservation Society Grant# F12AP00329 FWS: $64,702 Leveraged Funds: $40,327 Location: Cameroon The purpose of this project is to improve protection of chimpanzees and gorillas at Deng Deng NP by developing a strong local constituency for conservation and training park ecoguards in law enforcement, natural resource management, and monitoring of illegal activities. Promoting Community Participation in Great Ape Conservation in the Proposed Ebo National Park, Cameroon. GA-0924 Zoological Society of San Diego Grant# F12AP00679 FWS: $70,662 Leveraged Funds: $183,729 Location: Cameroon The purpose of this project is to reduce illegal hunting of great apes and other wildlife by engaging local communities, traditional authorities, and government agencies in a program of outreach, education, and awareness. DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO Ensuring continued growth of the Virunga Mountain -

In Full Swing: an Assessment of Trade in Orang-Utans and Gibbons on Java and Bali, Indonesia

IN FULL SWING: AN ASSESSMENT OF TRADE IN ORANG-UTANS AND GIBBONS ON JAVA AND BALI,INDONESIA VINCENT NIJMAN A TRAFFIC SOUTHEAST ASIA REPORT TRAFFIC SOUTHEAST ASIA Published by TRAFFIC Southeast Asia, Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia © 2005 TRAFFIC Southeast Asia All rights reserved. All material appearing in this publication is copyrighted and may be produced with permission. Any reproduction in full or in part of this publication must credit TRAFFIC Southeast Asia as the copyright owner. The views of the authors expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of the TRAFFIC Network, WWF or IUCN. The designations of geographical entities in this publication, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of TRAFFIC or its supporting organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The TRAFFIC symbol copyright and Registered Trademark ownership is held by WWF, TRAFFIC is a joint programme of WWF and IUCN. Layout by Noorainie Awang Anak, TRAFFIC Southeast Asia Suggested citation: Vincent Nijman (2005). In Full Swing: An Assessment of trade in Orang-utans and Gibbons on Java and Bali, Indonesia. TRAFFIC Southeast Asia ISBN 983-3393-00-4 Photograph credit: Orang-utan, Pongo pygmaeus, Sepilok Orang-utan Rehabilitation Centre, Sabah, Malaysia (WWF-Malaysia/Cede Prudente) IN FULL SWING: AN ASSESSMENT OF TRADE IN ORANG-UTANS AND GIBBONS ON JAVA AND BALI,INDONESIA -

The World's 25 Most Endangered Primates, 2006-2008

Primate Conservation 2007 (22): 1 – 40 Primates in Peril: The World’s 25 Most Endangered Primates, 2006 – 2008 Russell A. Mittermeier 1, Jonah Ratsimbazafy 2, Anthony B. Rylands 3, Liz Williamson 4, John F. Oates 5, David Mbora 6, Jörg U. Ganzhorn 7, Ernesto Rodríguez-Luna 8, Erwin Palacios 9, Eckhard W. Heymann 10, M. Cecília M. Kierulff 11, Long Yongcheng 12, Jatna Supriatna 13, Christian Roos 14, Sally Walker 15, and John M. Aguiar 3 1Conservation International, Arlington, VA, USA 2Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust – Madagascar Programme, Antananarivo, Madagascar 3Center for Applied Biodiversity Science, Conservation International, Arlington, VA, USA 4Department of Psychology, University of Stirling, Stirling, Scotland, UK 5Department of Anthropology, Hunter College, City University of New York (CUNY), New York, USA 6Department of Biological Sciences, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH, USA 7Institute of Zoology, Ecology and Conservation, Hamburg, Germany 8Instituto de Neuroetología, Universidad Veracruzana, Veracruz, México 9Conservation International Colombia, Bogotá, DC, Colombia 10Abteilung Verhaltensforschung & Ökologie, Deutsches Primatenzentrum, Göttingen, Germany 11Fundação Parque Zoológico de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil 12The Nature Conservancy, China Program, Kunming, Yunnan, China 13Conservation International Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia 14 Gene Bank of Primates, Deutsches Primatenzentrum, Göttingen, Germany 15Zoo Outreach Organisation, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, India Introduction among primatologists working in the field who had first-hand knowledge of the causes of threats to primates, both in gen- Here we report on the fourth iteration of the biennial eral and in particular with the species or communities they listing of a consensus of 25 primate species considered to study. The meeting and the review of the list of the World’s be amongst the most endangered worldwide and the most in 25 Most Endangered Primates resulted in its official endorse- need of urgent conservation measures. -

Northern White-Cheeked Gibbon • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Nomascus Leucogenys•

Northern White-cheeked Gibbon • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Nomascus leucogenys• Classification What groups does this organism belong to based on characteristics shared with other organisms? Class: Mammalia (all mammals) Order: Primates (prosimians, monkeys, apes, humans) Family: Hylobatidae(gibbons and lesser apes) Genus: Nomascus (crested gibbons) Species: Nomascus leucogenys (Northern white cheeked gibbon) Distribution Where in the world does this species live? Nomascus leucogenys is better known as the white-cheeked gibbon. This species is found only in Southeast Asia. They primarily populate Laos, Vietnam, and Southern China. In Vietnam white-cheeked gibbons are found to the southwest of the Song Ma and Song Bo Rivers. Habitat What kinds of areas does this species live in? They live in the canopy of subtropical rainforests and prefer lowland forests with more diversity of fruit trees. However more recently with habitat loss most of these gibbons live above 700 meters.White- cheeked gibbons hardly ever descend to the forest floor. Physical Description How would this animal’s body shape and size be described? • Gibbons are small apes with very long arms and no tail. Nomascus leucogenys are not sexually dimorphic for size, but are for color. • Males and females are 45-63 cm (18-25 in) long and weigh and average of 5.7 kg.(12.5 lb). • All infants are born with cream-colored fur. At two years of age, the infants’ fur changes from cream to black, and they develop white patches on their cheeks. • At sexual maturity, males stay black with white cheeks. Females turn back to the original cream or pale yellow/yellow color and they lose the majority of their white cheek color, except for a thin white face ring. -

Silvery Gibbon Fact Sheet

PO BOX 335 COMO 6952 WESTERN AUSTRALIA Website: www.silvery.org.au E-mail: [email protected] Phone: 61 402 046 950 Silvery Gibbon Fax: 61 8 9331 4317 Fact Sheet SCIENTIFIC NAME: Hylobates moloch OTHER NAMES: Javan Gibbon, Owa Jawa IUCN STATUS CATEGORY: Endangered (IUCN Red List 2010) HABITAT: Silvery gibbons are arboreal and live in primary and secondary tropical rainforest, from sea level up to 1500m above sea level. GEOGRAPHICAL SPREAD: The Silvery Gibbon is found only on the island of Java, Indonesia (circled in map). Previously Silvery Gibbon habitat extended throughout the whole of the West Java and Banten provinces, through the southern half of the Central Java provinces and the whole Map of Indonesia (Yahoo Maps). Silvery Gibbons are only found on the island of Java (circled) in the central Yogyakarta area. Current populations are found and western areas only in West Java and the western parts of Central Java. They are the only gibbon species found in Java. CURRENT POPULATION: While the exact number of silvery gibbons left in the wild is unknown, it is estimated that less than 2500 gibbons remain, existing in fragmented areas of forest. The funding of accurate and up to date surveys of the current wild populations and the remaining areas of habitat is a priority for the Silvery Gibbon Project. This information is vital in order to determine which areas of forest are of greatest priority for forest protection and education programs. REASONS FOR DECLINE: Previous habitat loss through deforestation, logging and encroaching human population pressures have been instrumental in the decline of the Silvery Gibbon.