Affixes and Tone in Aguata Igbo: a Critical Appraisal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SIGNIFICANCE of ANIMAL MOTIFS in INDIGENOUS ULI BODY and WALL PAINTINGS Nkiruka Jane Uju Nwafor Department of Fine and Applied A

Mgbakoigba, Journal of African Studies. Vol. 8, No. 1. June 2019 SIGNIFICANCE OF ANIMAL MOTIFS IN INDIGENOUS ULI BODY AND WALL PAINTINGS… Nkiruka Jane Uju Nwafor SIGNIFICANCE OF ANIMAL MOTIFS IN INDIGENOUS ULI BODY AND WALL PAINTINGS Nkiruka Jane Uju Nwafor Department of Fine and Applied Arts Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka. [email protected] This article explores the significance of animal motifs in traditional Uli body and wall paintings. A critical assessment and understanding of the philosophical import of animals in African concept of existence is vital for an in-depth appreciation of their (animals’) symbols in indigenous African artworks. This paper attempts to a draw parallel between traditional beliefs concerning certain animals among the Igbo of south-eastern Nigeria and motifs derived from indigenous Uli body and wall painting. In essence, the article sees animal motifs in Uli body and wall paintings as playing an aesthetic as well as metaphysical roles. Hence I argue that local nuances of religiosity and spirituality have historically imbued the animals with a heightened sense of sacredness in some Igbo communities thus allowing the animals to occupy a mystical space in Igbo cosmology. Introduction The pre-colonial system of knowledge transmission in Africa was not only through oral literature but also through the varied artistic traditions that survived from one generation to the other. The rich heritage of ancient Egyptian arts (including the hieroglyphs), the numerous Neolithic rock paintings and engravings found in Northern Africa, which dates back to 5000 and 2000 BCE respectively were mainly symbolic of vital occurrences of the past, documented through art (Getlein 2002: 335). -

The Igbo Traditional Food System Documented in Four States in Southern Nigeria

Chapter 12 The Igbo traditional food system documented in four states in southern Nigeria . ELIZABETH C. OKEKE, PH.D.1 . HENRIETTA N. ENE-OBONG, PH.D.1 . ANTHONIA O. UZUEGBUNAM, PH.D.2 . ALFRED OZIOKO3,4. SIMON I. UMEH5 . NNAEMEKA CHUKWUONE6 Indigenous Peoples’ food systems 251 Study Area Igboland Area States Ohiya/Ohuhu in Abia State Ubulu-Uku/Alumu in Delta State Lagos Nigeria Figure 12.1 Ezinifite/Aku in Anambra State Ede-Oballa/Ukehe IGBO TERRITORY in Enugu State Participating Communities Data from ESRI Global GIS, 2006. Walter Hitschfield Geographic Information Centre, McGill University Library. 1 Department of 3 Home Science, Bioresources Development 5 Nutrition and Dietetics, and Conservation Department of University of Nigeria, Program, UNN, Crop Science, UNN, Nsukka (UNN), Nigeria Nigeria Nigeria 4 6 2 International Centre Centre for Rural Social Science Unit, School for Ethnomedicine and Development and of General Studies, UNN, Drug Discovery, Cooperatives, UNN, Nigeria Nsukka, Nigeria Nigeria Photographic section >> XXXVI 252 Indigenous Peoples’ food systems | Igbo “Ndi mba ozo na-azu na-anwu n’aguu.” “People who depend on foreign food eventually die of hunger.” Igbo saying Abstract Introduction Traditional food systems play significant roles in maintaining the well-being and health of Indigenous Peoples. Yet, evidence Overall description of research area abounds showing that the traditional food base and knowledge of Indigenous Peoples are being eroded. This has resulted in the use of fewer species, decreased dietary diversity due wo communities were randomly to household food insecurity and consequently poor health sampled in each of four states: status. A documentation of the traditional food system of the Igbo culture area of Nigeria included food uses, nutritional Ohiya/Ohuhu in Abia State, value and contribution to nutrient intake, and was conducted Ezinifite/Aku in Anambra State, in four randomly selected states in which the Igbo reside. -

PROVISIONAL LIST.Pdf

S/N NAME YEAR OF CALL BRANCH PHONE NO EMAIL 1 JONATHAN FELIX ABA 2 SYLVESTER C. IFEAKOR ABA 3 NSIKAK UTANG IJIOMA ABA 4 ORAKWE OBIANUJU IFEYINWA ABA 5 OGUNJI CHIDOZIE KINGSLEY ABA 6 UCHENNA V. OBODOCHUKWU ABA 7 KEVIN CHUKWUDI NWUFO, SAN ABA 8 NWOGU IFIONU TAGBO ABA 9 ANIAWONWA NJIDEKA LINDA ABA 10 UKOH NDUDIM ISAAC ABA 11 EKENE RICHIE IREMEKA ABA 12 HIPPOLITUS U. UDENSI ABA 13 ABIGAIL C. AGBAI ABA 14 UKPAI OKORIE UKAIRO ABA 15 ONYINYECHI GIFT OGBODO ABA 16 EZINMA UKPAI UKAIRO ABA 17 GRACE UZOME UKEJE ABA 18 AJUGA JOHN ONWUKWE ABA 19 ONUCHUKWU CHARLES NSOBUNDU ABA 20 IREM ENYINNAYA OKERE ABA 21 ONYEKACHI OKWUOSA MUKOSOLU ABA 22 CHINYERE C. UMEOJIAKA ABA 23 OBIORA AKINWUMI OBIANWU, SAN ABA 24 NWAUGO VICTOR CHIMA ABA 25 NWABUIKWU K. MGBEMENA ABA 26 KANU FRANCIS ONYEBUCHI ABA 27 MARK ISRAEL CHIJIOKE ABA 28 EMEKA E. AGWULONU ABA 29 TREASURE E. N. UDO ABA 30 JULIET N. UDECHUKWU ABA 31 AWA CHUKWU IKECHUKWU ABA 32 CHIMUANYA V. OKWANDU ABA 33 CHIBUEZE OWUALAH ABA 34 AMANZE LINUS ALOMA ABA 35 CHINONSO ONONUJU ABA 36 MABEL OGONNAYA EZE ABA 37 BOB CHIEDOZIE OGU ABA 38 DANDY CHIMAOBI NWOKONNA ABA 39 JOHN IFEANYICHUKWU KALU ABA 40 UGOCHUKWU UKIWE ABA 41 FELIX EGBULE AGBARIRI, SAN ABA 42 OMENIHU CHINWEUBA ABA 43 IGNATIUS O. NWOKO ABA 44 ICHIE MATTHEW EKEOMA ABA 45 ICHIE CORDELIA CHINWENDU ABA 46 NNAMDI G. NWABEKE ABA 47 NNAOCHIE ADAOBI ANANSO ABA 48 OGOJIAKU RUFUS UMUNNA ABA 49 EPHRAIM CHINEDU DURU ABA 50 UGONWANYI S. AHAIWE ABA 51 EMMANUEL E. -

Accountability and Internal Revenue Generation in the Local Government System in Anambra State (2006-2014) 1Nwokike, Chidi Emmanuel Phd* , 2

International Journal of Academic Management Science Research (IJAMSR) ISSN: 2643-900X Vol. 5 Issue 6, June - 2021, Pages: 87-96 Accountability and Internal Revenue Generation in The Local Government System In Anambra State (2006-2014) 1Nwokike, Chidi Emmanuel PhD* , 2. Ananti, M.O., 3Ebelechukwu Rebecca Okonkwo 1Department of Public Administration, Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu University. Igbariam Campus- Anambra State [email protected] 2Department of Public Administration, Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu University, Igbariam Campus- Anambra State 3Department of Public Administration, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka Abstract- This study investigated accountability and revenue generation in the local government system in Anambra state from 2006- 2014. The problem of poor revenue generation in local governments has been attributed to corrupt practices among revenue collectors and non-adherence to control mechanisms in Anambra state. To achieve these stated objectives, two research questions and hypotheses were raised. System theory was used to guide the study. It made use of descriptive survey design with a study population of 14,881 workers. It used a 5 point Likert scale structured questionnaire to elicit information from the respondents and the Chi-square statistical tool was to analyse the hypotheses. The study found that corruption among revenue collectors accounted for poor revenue base and that incompetence on the part of internal revenue collectors account for poor revenue generation by local governments in Anambra state. We recommended thus, amongst others that adequate machinery should be put in place to dictate and prosecute corrupt revenue collectors, and that proper documentation and auditing of funds generated, since these will encourage accountability and efficient management of public funds. -

World Bank Document

SFG1692 V36 Hospitalia Consultaire Ltd ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT PLAN (ESMP) Public Disclosure Authorized NNEWICHI GULLY EROSION SITE, NNEWI NORTH LGA, ANAMBRA STATE Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Anambra State Nigeria Erosion and Watershed Management Project Public Disclosure Authorized November 2017 Table of Contents List of Plates ..................................................................................................................... v List of Tables .................................................................................................................. vii list of acronyms ............................................................................................................. viii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................... ix 1 CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION ................................................................................ 17 1.1 Background ..................................................................................................................... 17 1.2 Hydrology ........................................................................................................................ 18 1.3 Hydrography .................................................................................................................... 19 1.4 Hydrogeology .................................................................................................................. 20 1.5 Baseline Information -

Research Report

1.1 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION Soil erosion is the systematic removal of soil, including plant nutrients, from the land surface by various agents of denudation (Ofomata, 1985). Water being the dominant agent of denudation initiates erosion by rain splash impact, drag and tractive force acting on individual particles of the surface soil. These are consequently transported seizing slope advantage for deposition elsewhere. Soil erosion is generally created by initial incision into the subsurface by concentrated runoff water along lines or zones of weakness such as tension and desiccation fractures. As these deepen, the sides give in or slide with the erosion of the side walls forming gullies. During the Stone Age, soil erosion was counted as a blessing because it unearths valuable treasures which lie hidden below the earth strata like gold, diamond and archaeological remains. Today, soil erosion has become an endemic global problem, In the South eastern Nigeria, mostly in Anambra State, it is an age long one that has attained a catastrophic dimension. This environmental hazard, because of the striking imprints on the landscape, has sparked off serious attention of researchers and government organisations for sometime now. Grove(1951); Carter(1958); Floyd(1965); Ofomata (1964,1965,1967,1973,and 1981); all made significant and refreshing contributions on the processes and measures to combat soil erosion. Gully Erosion is however the prominent feature in the landscape of Anambra State. The topography of the area as well as the nature of the soil contributes to speedy formation and spreading of gullies in the area (Ofomata, 2000);. 1.2 Erosion Types There are various types of erosion which occur these include Soil Erosion Rill Erosion Gully Erosion Sheet Erosion 1.2.1 Soil Erosion: This has been occurring for some 450 million years, since the first land plants formed the first soil. -

“Burn the Mmonwu” Contradictions and Contestations in Masquerade Perfor- Mance in Uga, Anambra State in Southeastern Nigeria

“Burn the Mmonwu” Contradictions and Contestations in Masquerade Perfor- mance in Uga, Anambra State in Southeastern Nigeria Charles Gore asked performances organized by male asso- ciations are a distinctive feature of public per- ALL PHOTOS BY THE AUTHOR formance among Igbo-speaking peoples of southeastern Nigeria (Jones 1984, Cole and Ania- kor 1984) and have been the subject of attention by African art historians in the twentieth cen- tury (Ottenberg 1975, Aniakor 1978, Ugonna 1984, Henderson and MUmunna 1988, Bentor 1995). Innovation and change in terms of iconography, ritual, and dramatic presentation have always been important components to these performances, as well as flexible adaptations and responses to changing social circumstances (Figs. 1–3). However, in the last two decades, new mass movements of Christian evangelism and Pentecostalism have emerged, success- fully exhorting their members to reject masquerade as a pagan practice. During this time, in many places in southeastern Nige- ria, famous and long-standing masquerade associations have dis- banded and their masks and costumes burnt as testimonies to the efficacy of Pentecostalism, affirming the successful conversion of former masquerade members. This research examines the chal- lenges that changing localized circumstances pose to masquerade practice in one locale in southeastern Nigeria. Uga1 is located in southeastern Nigeria in Aguata Local Gov- ernment Area (LGA) in Anambra state, along the Nnewi-Okigwe expressway in Nigeria, some 40 km (25 mi.) eastwards from Onitsha on the river Niger (Fig. 4). It consisted until recently of four village units—Umueze, Awarasi, Umuoru, and Oka—spa- tially contiguous with each other and has a population of some 20,000 individuals. -

Varieties of Igbo Dialect—A Study of Some Communities in Old Aguata Local Government Area

Journal of Literature and Art Studies, ISSN 2159-5836 December 2014, Vol. 4, No. 12, 1122-1128 D DAVID PUBLISHING Varieties of Igbo Dialect—A Study of Some Communities in Old Aguata Local Government Area Okoye Christiana Obiageli Federal Polytechnic Oko, Oko, Nigeria The Igbo language has grown and developed to what is known as Standard Igbo (Igbo Izugbe) today. Series of efforts have gone into the modification and invention of words to ensure wider acceptability and intelligibility. While this is a welcome idea, the tendency of the loss of communal identity in terms of the original local variety of the Igbo Language spoken by each community becomes very obvious. As Igbos can easily distinguish an Anambra man from an Imo man, it is also necessary that within Anambra, one should be able to locate a particular town in the area through the spoken Igbo Language variety. This paper studies some of these local variants and advocates for a method of preserving such rich cultural heritage which are so valuable for posterity. Keywords: Igbo, dialect, communities, Aguata Introduction The Oxford Advanced Learners Dictionary defines dialect as “form of a language (grammar, vocabulary and pronunciation) used in a part of a country or by a class of people”. The Wikipedia Free Encyclopedia traced its root to the ancient Greek word “dialektos” meaning discourse. In todays’ context and in this paper, it is used to refer to a variety or model of a language that is characteristic of a particular group of the speakers of that language. In other words, the language of their daily discourse. -

New Projects Inserted by Nass

NEW PROJECTS INSERTED BY NASS CODE MDA/PROJECT 2018 Proposed Budget 2018 Approved Budget FEDERAL MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE AND RURAL SUPPLYFEDERAL AND MINISTRY INSTALLATION OF AGRICULTURE OF LIGHT AND UP COMMUNITYRURAL DEVELOPMENT (ALL-IN- ONE) HQTRS SOLAR 1 ERGP4145301 STREET LIGHTS WITH LITHIUM BATTERY 3000/5000 LUMENS WITH PIR FOR 0 100,000,000 2 ERGP4145302 PROVISIONCONSTRUCTION OF SOLAR AND INSTALLATION POWERED BOREHOLES OF SOLAR IN BORHEOLEOYO EAST HOSPITALFOR KOGI STATEROAD, 0 100,000,000 3 ERGP4145303 OYOCONSTRUCTION STATE OF 1.3KM ROAD, TOYIN SURVEYO B/SHOP, GBONGUDU, AKOBO 0 50,000,000 4 ERGP4145304 IBADAN,CONSTRUCTION OYO STATE OF BAGUDU WAZIRI ROAD (1.5KM) AND EFU MADAMI ROAD 0 50,000,000 5 ERGP4145305 CONSTRUCTION(1.7KM), NIGER STATEAND PROVISION OF BOREHOLES IN IDEATO NORTH/SOUTH 0 100,000,000 6 ERGP445000690 SUPPLYFEDERAL AND CONSTITUENCY, INSTALLATION IMO OF STATE SOLAR STREET LIGHTS IN NNEWI SOUTH LGA 0 30,000,000 7 ERGP445000691 TOPROVISION THE FOLLOWING OF SOLAR LOCATIONS: STREET LIGHTS ODIKPI IN GARKUWARI,(100M), AMAKOM SABON (100M), GARIN OKOFIAKANURI 0 400,000,000 8 ERGP21500101 SUPPLYNGURU, YOBEAND INSTALLATION STATE (UNDER OF RURAL SOLAR ACCESS STREET MOBILITY LIGHTS INPROJECT NNEWI (RAMP)SOUTH LGA 0 30,000,000 9 ERGP445000692 TOSUPPLY THE FOLLOWINGAND INSTALLATION LOCATIONS: OF SOLAR AKABO STREET (100M), LIGHTS UHUEBE IN AKOWAVILLAGE, (100M) UTUH 0 500,000,000 10 ERGP445000693 ANDEROSION ARONDIZUOGU CONTROL IN(100M), AMOSO IDEATO - NCHARA NORTH ROAD, LGA, ETITI IMO EDDA, STATE AKIPO SOUTH LGA 0 200,000,000 11 ERGP445000694 -

List of Coded Health Facilities in Anambra State.Pdf

Anambra State Health Facility Listing LGA WARD NAME OF HEALTH FACILITY FACILITY TYPE OWERSHIP CODE (PUBLIC/ PRIVATE) LGA STATE OWERSHIP FACILITYTYPE FACILITYNUMBER Primary Health Centre Oraeri Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0001 Primary Health Centre Akpo Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0002 Ebele Achina PHC Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0003 Primary Health Centre Aguata Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0004 Primary Health Centre Ozala Isuofia Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0005 Primary Health Centre Uga Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0006 Primary Health Centre Mkpologwu Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0007 Primary Health Centre Ikenga Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0008 Health Centre Ekwusigo Isuofia Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0009 Primary Health Centre Amihie Umuchu Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0010 Obimkpa Achina Health Centre Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0011 Primary Health Centre Amesi Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0012 Primary Health Centre Ezinifite Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0013 Primary Health Centre Ifite Igboukwu Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0014 Health Post Amesi Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0015 Isiaku Health Post Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0016 Analasi Uga Health Post Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0017 Ugwuakwu Umuchu Health Post Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0018 Aguluezechukwu Health Post Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0019 Health Centre Umuona Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0020 Health Post Akpo Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0021 Health Center, Awa Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0022 General Hospital Ekwuluobia Secondary Public 04 01 1 1 0023 General Hospital Umuchu Secondary Public 04 01 2 1 0024 Comprehensive Health Centre Achina Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0025 Catholic Visitation Hospital, Umuchu Secondary Private 04 01 2 2 0026 Continental Hospital Ekwulobia Primary Private 04 01 1 2 0027 Niger Hospital Igboukwu Primary Private 04 01 1 2 0028 Dr. -

States and Lcdas Codes.Cdr

PFA CODES 28 UKANEFUN KPK AK 6 CHIBOK CBK BO 8 ETSAKO-EAST AGD ED 20 ONUIMO KWE IM 32 RIMIN-GADO RMG KN KWARA 9 IJEBU-NORTH JGB OG 30 OYO-EAST YYY OY YOBE 1 Stanbic IBTC Pension Managers Limited 0021 29 URU OFFONG ORUKO UFG AK 7 DAMBOA DAM BO 9 ETSAKO-WEST AUC ED 21 ORLU RLU IM 33 ROGO RGG KN S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 10 IJEBU-NORTH-EAST JNE OG 31 SAKI-EAST GMD OY S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 2 Premium Pension Limited 0022 30 URUAN DUU AK 8 DIKWA DKW BO 10 IGUEBEN GUE ED 22 ORSU AWT IM 34 SHANONO SNN KN CODE CODE 11 IJEBU-ODE JBD OG 32 SAKI-WEST SHK OY CODE CODE 3 Leadway Pensure PFA Limited 0023 31 UYO UYY AK 9 GUBIO GUB BO 11 IKPOBA-OKHA DGE ED 23 ORU-EAST MMA IM 35 SUMAILA SML KN 1 ASA AFN KW 12 IKENNE KNN OG 33 SURULERE RSD OY 1 BADE GSH YB 4 Sigma Pensions Limited 0024 10 GUZAMALA GZM BO 12 OREDO BEN ED 24 ORU-WEST NGB IM 36 TAKAI TAK KN 2 BARUTEN KSB KW 13 IMEKO-AFON MEK OG 2 BOSARI DPH YB 5 Pensions Alliance Limited 0025 ANAMBRA 11 GWOZA GZA BO 13 ORHIONMWON ABD ED 25 OWERRI-MUNICIPAL WER IM 37 TARAUNI TRN KN 3 EDU LAF KW 14 IPOKIA PKA OG PLATEAU 3 DAMATURU DTR YB 6 ARM Pension Managers Limited 0026 S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 12 HAWUL HWL BO 14 OVIA-NORTH-EAST AKA ED 26 26 OWERRI-NORTH RRT IM 38 TOFA TEA KN 4 EKITI ARP KW 15 OBAFEMI OWODE WDE OG S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 4 FIKA FKA YB 7 Trustfund Pensions Plc 0028 CODE CODE 13 JERE JRE BO 15 OVIA-SOUTH-WEST GBZ ED 27 27 OWERRI-WEST UMG IM 39 TSANYAWA TYW KN 5 IFELODUN SHA KW 16 ODEDAH DED OG CODE CODE 5 FUNE FUN YB 8 First Guarantee Pension Limited 0029 1 AGUATA AGU AN 14 KAGA KGG BO 16 OWAN-EAST -

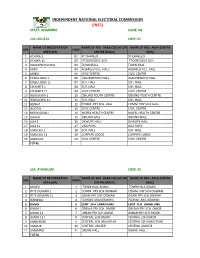

State: Anambra Code: 04

INDEPENDENT NATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMISSION (INEC) STATE: ANAMBRA CODE: 04 LGA :AGUATA CODE: 01 NAME OF REGISTRATION NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA CENTRE S/N CODE AREA (RA) CENTRE (RACC) (RAC) 1 ACHINA 1 01 ST CHARLED ST CHARLED 2 ACHINA 11 02 PTOGRESSIVE SCH. PTOGRESSIVE SCH. 3 AGULEZECHUKWU 03 TOWN HALL TOWN HALL 4 AKPO 04 AGBAELU VILL. HALL AGBAELU VILL. HALL 5 AMESI 05 CIVIC CENTRE CIVIC CENTRE 6 EKWULOBIA 1 06 UMUEZENOFO HALL. UMUEZENOFO HALL. 7 EKWULOBIA 11 07 SCH. HALL SCH. HALL 8 EZENIFITE 1 08 SCH. HALL SCH. HALL 9 EZENIFITE 11 09 CIVIC CENTRE CIVIC CENTRE 10 IGBOUKWU 1 10 OBIUNO YOUTH CENTRE OBIUNO YOUTH CENTRE 11 IGBOUKWU 11 11 SCH. HALL SCH. HALL 12 IKENGA 12 COMM. PRY SCH. HALL COMM. PRY SCH. HALL 13 ISUOFIA 13 CIVIC CENTRE CIVIC CENTRE 14 NKPOLOGWU 14 MOFEL HEALTH CENTRE MOFEL HEALTH CENTRE 15 ORAERI 15 OBIUNO HALL OBIUNO HALL 16 UGA 1 16 OKWUTE HALL OKWUTE HALL 17 UGA 11 17 UGA BOYS UGA BOYS 18 UMUCHU 1 18 SCH. HALL SCH. HALL 19 UMUCHU 11 19 CORPERS LODGE CORPERS LODGE 20 UMOUNA 20 CIVIC CENTRE CIVIC CENTRE TOTAL LGA: AYAMELUM CODE: 02 NAME OF REGISTRATION NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA CENTRE S/N CODE AREA (RA) CENTRE (RACC) (RAC) 1 ANAKU 1 TOWN HALL ANAKU TOWN HALL ANAKU 2 IFITE OGWARI 1 2 COMM. PRY SCH.OGWARI COMM. PRY SCH.OGWARI 3 IFITE OGWARI 11 3 OGARI PRY SCH.OGWARI OGARI PRY SCH.OGWARI 4 IGBAKWU 4 ISIOKWE ARA,IGBAKWU ISIOKWE ARA,IGBAKWU 5 OMASI 5 CENT.