The Realisation of Our Perceptions of the World in the Forms of Space and Time Is the Only Aim of Our Pictorial and Plastic Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Open Etoth Dissertation Corrected.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School The College of Arts and Architecture FROM ACTIVISM TO KIETISM: MODERIST SPACES I HUGARIA ART, 1918-1930 BUDAPEST – VIEA – BERLI A Dissertation in Art History by Edit Tóth © 2010 Edit Tóth Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2010 The dissertation of Edit Tóth was reviewed and approved* by the following: Nancy Locke Associate Professor of Art History Dissertation Adviser Chair of Committee Sarah K. Rich Associate Professor of Art History Craig Zabel Head of the Department of Art History Michael Bernhard Associate Professor of Political Science *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School ii ABSTRACT From Activism to Kinetism: Modernist Spaces in Hungarian Art, 1918-1930. Budapest – Vienna – Berlin investigates modernist art created in Central Europe of that period, as it responded to the shock effects of modernity. In this endeavor it takes artists directly or indirectly associated with the MA (“Today,” 1916-1925) Hungarian artistic and literary circle and periodical as paradigmatic of this response. From the loose association of artists and literary men, connected more by their ideas than by a distinct style, I single out works by Lajos Kassák – writer, poet, artist, editor, and the main mover and guiding star of MA , – the painter Sándor Bortnyik, the polymath László Moholy- Nagy, and the designer Marcel Breuer. This exclusive selection is based on a particular agenda. First, it considers how the failure of a revolutionary reorganization of society during the Hungarian Soviet Republic (April 23 – August 1, 1919) at the end of World War I prompted the Hungarian Activists to reassess their lofty political ideals in exile and make compromises if they wanted to remain in the vanguard of modernity. -

Art Masterpiece: Pisa II, by Al Held Keywords

Art Masterpiece: Pisa II, by Al Held Keywords: Abstract Expressionism, Kinetic Art/Op-Art, Geometric Grade(s): Activity: Optical-Art 3-D hand drawing About the Artist: Al Held, born in Brooklyn, New York, on October 12, 1928. He was a high-school drop-out who joined the Navy and discovered an interest in art. He later became a Professor at Yale University. Held touched on several styles of art from Abstract Expressionism to Op- Art, Illusionism, Minimalism, and Hard Edge. Abstract Expressionism is a style of artwork that is focused on expressing a feeling through the use of color and shape. Held developed his geometric form of abstraction by blending the randomly dripped painting style of Jackson Pollack with the meticulously ordered canvases of Piet Mondrian. Held used straight edges, masking tape and multiple coats of evenly applied paint to create works with intersecting lines, overlapping circles, triangles and other geometric figures. With subtle splashes of color and illusions of Chandler Unified School District Art Masterpiece Program, Chandler, Arizona, USA three-dimensional depth, the paintings could, in the words of one critic, be "disorienting to the point of vertigo." Busy until the end, Held could command more than $1million for his monumental works. He felt proprietary about his paintings along after completed. He would oversee a team of artists whenever his murals needed touching up. About the Artwork: Pisa II is a work that exemplifies the intersection of math and art. The painting was created during a time when abstract art was gaining prominence all over the world, particularly in America. -

Cybernetics in Society and Art

Stephen Jones Visiting Fellow, College of Fines Arts, University of NSW [email protected] Cybernetics in Society and Art Abstract: This paper argues that cybernetics is a description of systems in conversation: that is, it is about systems “talk- ing” to each other, engaging in processes through which information is communicated or exchanged between each system or each element in a particular system, say a body or a society. It proposes that cybernetics de- scribes the process, or mechanism, that lies at the basis of all conversation and interaction and that this factor makes it valuable for the analysis of not only electronic communication systems but also of societal organisation and intra-communication and for interaction within the visual/electronic arts. The paper discusses the actual process of Cybernetics as a feedback driven mechanism for the self-regulation of a collection of logically linked objects (i.e., a system). These may constitute a machine of some sort, a biological body, a society or an interactive artwork and its interlocutors. The paper then looks at a variety of examples of systems that operate through cybernetic principles and thus demonstrate various aspects of the cybernetic pro- cess. After a discussion of the basic principles using the primary example of a thermostat, the paper looks at Stafford Beer's Cybersyn project developed for the self-regulation of the Chilean economy. Following this it examines the conversational, i.e., interactive, behaviour of a number of artworks, beginning with Gordon Pask's Colloquy of Mobiles developed for Cybernetic Serendipity in 1968. It then looks at some Australian and inter- national examples of interactive art that show various levels of cybernetic behaviours. -

From Mind to Machine, Computer Drawing in Art History

FROM MIND TO MACHINE: COMPUTER DRAWING IN ART HISTORY Constructing rules or sets of pre-determined instructions to produce art, has precedents within art The computer like any tool or machine, extends human history. Influenced by aspects of Constructivism, Op capabilities. But it is unique in that it extends the Art, Systems Art and Conceptualism and Concrete art, power of the mind as well as the hand. methodologies were discovered that laid a foundation for Robert Mallary 1 computer arts to develop and provided an inspiration to artists working in a programmatic way. Further, this This exhibition presents three major pioneers of approach had relevance to the times – Cordeiro wrote computer art – Waldemar Cordeiro, Robert Mallary and that Concrete art and Constructivism were movements Vera Molnár, from three different corners of the globe – that “helped create a ‘machine language’ appropriate to South America, the United States and Europe. Although the communications systems of the urban and industrial each has an original style and distinctive approach, so cie ty.” 2 with these works can be seen a similar modernist aesthetic and common interest in exploiting the unique These artists were thinking about a systematic way of capabilities inherent in the computer. It is evident working before they had access to computers. Molnár’s that complex and visually arresting imagery can arise speaks of a “machine imaginaire,” her name for her from relatively simple sets of instructions. method of conceptualising a system to dictate the drawing, without having access to digital technology. Before the onset of personal computers, propriety software and the Internet, artists had to learn to Paul Klee’s process driven approach to drawing – “an programme, work with scientists and technicians and active line on a walk…”3 was also an inspiration to often construct or adapt hardware in order to create pioneers who found a parallel with the crafting of code their work. -

Early British Computer-Generated Art Film BITS in MOTION

BITS IN MOTION: Early British Computer-Generated Art Film BITS IN MOTION A programme for the NFT of films made by British pioneers of computer animation [INTRODUCTION] The earliest computer animators had no off-the-shelf software packages, Programme Notes no online tutorials and nothing to buy in a bookshop on how to make animated films using computers. When they began to experiment with 7 March 2006 computer-generated imagery, they had to gain access to rare and specia- lised mainframes and learn programming from the ground up. As pioneers, they were making the first steps towards the highly successful CGI animations of the 21st century. The practitioners in this survey were among those who forged alliances with scientists and institutions, learned to write code, built or customised their own hardware where necessary and discovered imaginative ways to bend the available technology to suit their creative requirements. Working with equipment designed for completely different purposes was a difficult task requiring long hours, dedication and a particular type of mind-set but it led to highly productive cross- disciplinary working relationships. These films remain important examples of the collaboration possible between artists and technologists in this period. The CACHe Project has rediscovered some of the very first efforts in this medium and this event, supported by the London Centre for Arts and Cultural Enterprises, hopes to make its origins better known. // Recently completed in the School of History of Art, Film & Visual Media at Birkbeck, University of London, the CACHe (Computer Arts, Contexts, Histories, etc) Project was supported by the Arts and Humanities Research Council and traced the inception, growth and development of British computer arts from its origins in the 1960s to the beginning of the 1980s (www.bbk.ac.uk/hosted/cache). -

Sternberg Press / Style Sheet

STERNBERG PRESS / STYLE SHEET • Titles: First and all significant words in text/essay titles are capitalized • Titles of books, artworks, films, musical albums etc. are italicized • Titles of exhibitions, essays, poems, songs, short stories, etc. appear within double quotation marks (“ ”) • Punctuation: following American standards, punctuation appears within the quotation marks (with the exception of colons or semi-colons, i.e. “free speech”:). Also consistent with American standards, a serial comma is used in a phrase with three or more elements, preceding an “and,” “or,” etc.: “There were lectures, performances, and screenings.” • Quoted material: All quotes appear within double (“ ”) quotation marks. The same is the case with words used by an author in a pejorative (critical/disbelieving/sardonic) way, i.e. I became a “serious” artist. Single quotations appear only when there is a quotation within a quotation. Quotations within block quotations should be contained with double quotation marks. • Foreign words and words that need special emphasis are italicized, although the use of italics for emphasis should be done sparingly. • Artistic/Architectural styles: Names of specific artistic styles are uppercased unless they are used in a context that does not refer to their specific art-historical meaning, however “modernism” is always lowercase. Example 1: “Her piece was characteristically minimalistic.” Example 2: “This sculpture bears all the markings of the Minimalist movement.” • Dates/Years: Consistent with American format: February 6, 2005 / 1960s / 1990 / centuries are spelled out, i.e. the twentieth century, and hyphenated when used as an adjective, i.e. twentieth-century architecture. Abbreviated decades are written with an apostrophe (not single quotation mark) (i.e., ’60s). -

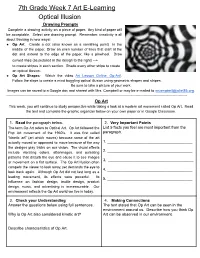

7Th Grade Week 7 Art E-Learning Optical Illusion

7 th Grade Week 7 Art E-Learning Optical Illusion Drawing Prompts Complete a drawing activity on a piece of paper. Any kind of paper will be acceptable. Select one drawing prompt. Remember, creativity is all about thinking in new ways! ● Op Art: Create a dot (also known as a vanishing point) in the middle of the paper. Draw an even number of lines that start at the dot and extend to the edge of the paper, like a pinwheel. Draw curved lines (as pictured in the design to the right) → to create stripes in each section. Shade every other stripe to create an optical illusion. ● Op Art Shapes : Watch the video Art Lesson Online: Op-Art!. Follow the steps to create a mind boggling optical illusion using geometric shapes and stripes. Be sure to take a picture of your work. Images can be saved to a Google doc and shared with Mrs. Campbell or may be e-mailed to m [email protected]. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Op Art This week, you will continue to study perspective while taking a look at a modern art movement called Op Art. Read the text and complete the graphic organizer below on your own paper or in Google Classroom. 1. Read the paragraph below. 2. Very Important Points The term Op Art refers to Optical Art. Op Art followed the List 5 facts you feel are most important from the Pop Art movement of the 1960’s. It was first called paragraph. “kinetic art” (art which moves) because some of the art actually moved or appeared to move because of the way 1. -

Operative Media (Art) Preservation

OPERATIVE MEDIA (ART) PRESERVATION. Adopting to the techno- logical time regime Lecture at Media Art Preservation Symposium, March 23/24 2017, Museum of Contemporary Art (Ludwig Museum), Budapest [long version] Preserving the signal: Media theory in support of media art preservation Preservation of media art does not simply require care for the material endurance of the artefact any more. Preservation of time-based technologies itself must be processual, as an ongoing act of up-dating the analog or digital art work.1 Still, a media-archaeological veto insists: To what degree does the hardware of so-called "born-digital" art matter? That is the moment when conservation specialists ask for epistemological advice. It is the primary task of media theory to take philosophical care of technical terms like the "emulation" of early computational media art works by contemporary operating system. What seems evident on a practical level turns out to be a delicate challenge to the ethics of museum preservation. Media archaeology describes the techniques of cultural tradition and develops criteria for a philosophy of dealing with the tempor(e)alities of techno-logical agents. Any piece of media art is subject to time in its hardware embodiment (physical entropy), in its logical, almost time-invariant design (circuit diagrams and software codes), and in its actual time-critical processing. Any epistemology and aesthetics of media art preservation aks for the foundation of its arguments in the technological ground, against all seductions of reducing preservation of media art to its shere phenomenological appeal. There are different museological degrees for media art preservation: conceptual (design), functional (circuitry), and actually operative (time-critical) re-enactment. -

Anatol Stern and Stefan Themerson. on Europa And

Anatol Stern and Stefan Themerson and Stefan Anatol Stern Janusz Lachowski ANATOL STERN AND STEFAN THEMERSON. ON EUROPA AND THE FRIENDSHIP BETWEEN THE TWO AVANT-GARDE ARTISTS ON THE BASIS OF THEIR MUTUAL CORRESPONDENCE FROM THE YEARS 1959–1968 Anatol Stern (1899–1968) was a poet, one of the founders of Polish futur- ism, a prose and drama writer, literary critic, essayist and author of memo- rial sketches1 as well as a prolific scriptwriter and film journalist of the Pol- ish interwar period. His wife Alicja (1905–1993) was a translator of Russian literature, theatre critic, and columnist, also participating in film script writing. Towards the end of her life, she wrote a children’s book. Following her husband’s death, she took care of his manuscript collection, preparing previously unedited texts2 for publication and making their home archive available to literary researchers interested in Stern’s writing. Stefan Themerson (1910–1988) was a novelist, poet, essayist, philoso- pher, author of children’s literature, and composer; together with his wife Franciszka (1907–1988), he made experimental short films in interwar 4 Vol. 2016 Libraries Polish 1 Cf. i.a. A. Stern, Legendy naszych dni [The Legends of Our Days], Kraków 1969; idem, Poezja zbuntowana. Szkice i wspomnienia [Rebellious Poetry. Essays and Memories], revised and expanded edition, Warszawa 1970; idem, Głód jednoznaczności i inne szkice [The Craving for Unambiguity and Other Essays], Warszawa 1972. 2 Cf. A. Stern, Dom Appolinaire’a. Rzecz o polskości i rodzinie poety [Appolinaire’s Home. On the Poet’s Polishness and His Family], prepared for printing by A. -

Dare to Be Digital: Japan's Pioneering Contributions to Today's

Dare to be Digital: Japan's Author Jean Ippolito + 1.808.933.0819 Pioneering Contributions to Today's Art Department [email protected] International Art and Technology University of Hawaii at Hilo 200 West Kawili Street Movement Hilo, Hawaii USA 96720 A number of pioneering artists began experimenting with the com neer), Makoto Ohtake (architectural engineer), Koji Fujino (systems puter as a visual arts medium in the late 60s and early 70s when engineer), and Fujio Niwa (systems engineer). Komura was the only most fine-arts circles refused to recognize art made by computers as artist of the group, but the group's activities, as a whole, were of an a viable product of human creativity. This was the era of computer avant-garde art nature. All of the members were in their early twen punch cards, when the visual results of algorithmic input were noth ties. Reichardt describes their aim (stated in the group's manifesto) ing more than line drawings. Many of the forward-looking artists who as the restoration of man's innate rights of existence by means of were experimenting with this technology were not taken seriously by computer control.3 Most of their art pieces involved the transforma the established art venues, and were, in fact, often ostracized by tion of simple line drawings of well-known images, as in Running their peers.' More recently, the work of computer artists has begun to Cola is Africa, in which a contour drawing of a running man changes appear in general textbooks on the history of art, but each book fea to an outline of a Coca-Cola bottle and then to a line drawing of the lures one or two completely different artists. -

British Computer Art 1960-1980

White Heat Cold Logic British Computer Art 1960–1980 Edited by Paul Brown, Charlie Gere, Nicholas Lambert, and Catherine Mason The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England ( 2008 Birbeck College All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher. For information about special quantity discounts, please email [email protected] .edu. This book was set in Garamond 3 and Bell Gothic on 3B2 by Asco Typesetters, Hong Kong. Printed and bound in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data White heat cold logic : British computer art 1960–1980 / edited by Paul Brown . [et al.]. p. cm.—(Leonardo books) Includes bibliographical references and indexes. ISBN 978-0-262-02653-6 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Computer art—Great Britain. 2. Art, British—20th century. I. Brown, Paul, 1947 Oct. 23– N7433.84.G7W45 2008 776.0941—dc22 2008016997 10987654321 Index 010101: Art in Technological Times, 415 Air Force Office of Scientific Research, 192 2000 AD, 307 Air Loom, 412 2001: A Space Odyssey, 171, 224 AISB. See Society for the Study of Artificial 20th Century Fox, 201, 223 Intelligence and the Simulation of Behavior A&L. See Art & Language Alan Stone Gallery, 422 AA. See Architectural Association Albers, Josef, 265 AARON, 4, 134, 145, 147–150, 276– Aldeburgh Festival, 182 277, 396, 422 Aldermaston March, 164 Abel, Robert, 399 ALGOL, 328 Abstract expressionism, 249–250, 291 Alien, 188–189, 199, 201, 315, 326 Abstraction, 4, 32n18, 122, 124, 248–249, Alife. -

15901 NHCA-Arts Fall02.P65

This issue of NH Arts focuses on individual artists and creativity. According to the U.S. Census, New Hamp- shire is home to about 12,000 artists, which includes arts educators, graphic designers, and architects, as well as creative writers, visual artists, musicians, dancers, actors, and others who derive most of their income from art-making. As you will see on page 9, we have re-instituted an Individual Artist Advisory Committee to help us identify services and programs that best work for all types of artists living in New Hampshire. The committee is reviewing everything from the way we administer artist grants and rosters to the pros and cons of re-instituting an Artist Retreat. We will also be asking the committee to identify the issues, such as housing and health insurance, which most concern New Hampshire artists. Artist Services Coordinator Julie Mento will be taking the committee’s recommendations to the State Arts Councilors during this year for implementation in fiscal years 2004-2005. So if you are an artist and you have some ideas of your own that you would like us to consider, please feel free to contact Julie with your suggestions, [email protected]. Only about 3,000 of New Hampshire’s 12,000 artists have found their way on to the Arts Council’s mailing or e-news lists. Even fewer apply for grants, rosters, or percent for art projects. Although we do not have a great deal of money to give out, we do have a great deal of information on artist resources and can provide ways for New Hampshire artists to connect with each other, strengthening the state’s arts community.