Economics,Religion,God,Happiness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ten Nobel Laureates Say the Bush

Hundreds of economists across the nation agree. Henry Aaron, The Brookings Institution; Katharine Abraham, University of Maryland; Frank Ackerman, Global Development and Environment Institute; William James Adams, University of Michigan; Earl W. Adams, Allegheny College; Irma Adelman, University of California – Berkeley; Moshe Adler, Fiscal Policy Institute; Behrooz Afraslabi, Allegheny College; Randy Albelda, University of Massachusetts – Boston; Polly R. Allen, University of Connecticut; Gar Alperovitz, University of Maryland; Alice H. Amsden, Massachusetts Institute of Technology; Robert M. Anderson, University of California; Ralph Andreano, University of Wisconsin; Laura M. Argys, University of Colorado – Denver; Robert K. Arnold, Center for Continuing Study of the California Economy; David Arsen, Michigan State University; Michael Ash, University of Massachusetts – Amherst; Alice Audie-Figueroa, International Union, UAW; Robert L. Axtell, The Brookings Institution; M.V. Lee Badgett, University of Massachusetts – Amherst; Ron Baiman, University of Illinois – Chicago; Dean Baker, Center for Economic and Policy Research; Drucilla K. Barker, Hollins University; David Barkin, Universidad Autonoma Metropolitana – Unidad Xochimilco; William A. Barnett, University of Kansas and Washington University; Timothy J. Bartik, Upjohn Institute; Bradley W. Bateman, Grinnell College; Francis M. Bator, Harvard University Kennedy School of Government; Sandy Baum, Skidmore College; William J. Baumol, New York University; Randolph T. Beard, Auburn University; Michael Behr; Michael H. Belzer, Wayne State University; Arthur Benavie, University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill; Peter Berg, Michigan State University; Alexandra Bernasek, Colorado State University; Michael A. Bernstein, University of California – San Diego; Jared Bernstein, Economic Policy Institute; Rari Bhandari, University of California – Berkeley; Melissa Binder, University of New Mexico; Peter Birckmayer, SUNY – Empire State College; L. -

A Macroeconomic Approach to Optimal Unemployment Insurance: Applications†

American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 2018, 10(2): 182–216 https://doi.org/10.1257/pol.20160462 A Macroeconomic Approach to Optimal Unemployment Insurance: Applications† By Camille Landais, Pascal Michaillat, and Emmanuel Saez* In the United States, unemployment insurance UI is more generous when unemployment is high. This paper examines( ) whether this pol- icy is desirable. The optimal UI replacement rate is the Baily-Chetty replacement rate plus a correction term measuring the effect of UI on welfare through labor market tightness. Empirical evidence suggests that tightness is inefficiently low in slumps and inefficiently high in booms, and that an increase in UI raises tightness. Hence, the cor- rection term is positive in slumps but negative in booms, and optimal UI is indeed countercyclical. Since there remains some uncertainty about the empirical evidence, the paper provides a thorough sensi- tivity analysis. JEL E24, E32, J64, J65 ( ) n the United States, unemployment insurance UI is more generous when ( ) Iunemployment is high. This policy started as an exceptional measure after the 1957–1958 recession and became a permanent program in 1970. Despite its long history, the policy remains debated. This paper examines whether the policy is desir- able from a welfare perspective. We conduct the welfare analysis in a matching model. We extend the static model from a companion paper Landais, Michaillat, and Saez 2018 into a dynamic model ( ) better suited for quantitative applications Section I . The model features most ( ) effects discussed in the policy debate: the effects of UI on job search, on wages, on job vacancies, and on aggregate unemployment.1 The optimal generosity of UI is given by a sufficient-statistic formula: the optimal replacement rate equals the Baily-Chetty replacement rate, a well-researched entity, plus a correction term mea- suring the effect of UI on social welfare through labor market tightness. -

PETER A. DIAMOND Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Cambridge, MA, U.S.A

UNEMPLOYMENT, VACANCIES, WAGES1 Prize Lecture, December 8, 2010 by PETER A. DIAMOND Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Cambridge, MA, U.S.A. We have all visited several stores to check prices and/or to find the right item or the right size. Similarly, it can take time and effort for a worker to find a suitable job with suitable pay and for employers to receive and evaluate applications for job openings. Search theory explores the workings of markets once facts such as these are incorporated into the analysis. Adequate analysis of market frictions needs to consider how reactions to frictions change the overall economic environment: not only do frictions change incentives for buyers and sellers, but the responses to the changed incentives also alter the economic environment for all the participants in the market. Because of these feedback effects, seemingly small frictions can have large effects on outcomes. Equilibrium search theory is the development of basic models to permit analysis of economic outcomes when specific frictions are incorporated into simpler market models. The primary friction addressed by search theory is the need to spend time and effort to learn about opportunities – opportunities to buy or to sell, to hire or to be hired. There are many aspects of a job and of a worker that matter when deciding whether a particular match is worth- while. Such frictions are naturally analyzed in models that consider a process over time – of workers seeking jobs, firms seeking employees, borrowers seeking lenders, and shoppers buying items that are not part of frequent shopping. Search theory models have altered the way we think about markets, how we interpret market data and how we think about government policies. -

ΒΙΒΛΙΟΓ ΡΑΦΙΑ Bibliography

Τεύχος 53, Οκτώβριος-Δεκέμβριος 2019 | Issue 53, October-December 2019 ΒΙΒΛΙΟΓ ΡΑΦΙΑ Bibliography Βραβείο Νόμπελ στην Οικονομική Επιστήμη Nobel Prize in Economics Τα τεύχη δημοσιεύονται στον ιστοχώρο της All issues are published online at the Bank’s website Τράπεζας: address: https://www.bankofgreece.gr/trapeza/kepoe https://www.bankofgreece.gr/en/the- t/h-vivliothhkh-ths-tte/e-ekdoseis-kai- bank/culture/library/e-publications-and- anakoinwseis announcements Τράπεζα της Ελλάδος. Κέντρο Πολιτισμού, Bank of Greece. Centre for Culture, Research and Έρευνας και Τεκμηρίωσης, Τμήμα Documentation, Library Section Βιβλιοθήκης Ελ. Βενιζέλου 21, 102 50 Αθήνα, 21 El. Venizelos Ave., 102 50 Athens, [email protected] Τηλ. 210-3202446, [email protected], Tel. +30-210-3202446, 3202396, 3203129 3202396, 3203129 Βιβλιογραφία, τεύχος 53, Οκτ.-Δεκ. 2019, Bibliography, issue 53, Oct.-Dec. 2019, Nobel Prize Βραβείο Νόμπελ στην Οικονομική Επιστήμη in Economics Συντελεστές: Α. Ναδάλη, Ε. Σεμερτζάκη, Γ. Contributors: A. Nadali, E. Semertzaki, G. Tsouri Τσούρη Βιβλιογραφία, αρ.53 (Οκτ.-Δεκ. 2019), Βραβείο Nobel στην Οικονομική Επιστήμη 1 Bibliography, no. 53, (Oct.-Dec. 2019), Nobel Prize in Economics Πίνακας περιεχομένων Εισαγωγή / Introduction 6 2019: Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo and Michael Kremer 7 Μονογραφίες / Monographs ................................................................................................... 7 Δοκίμια Εργασίας / Working papers ...................................................................................... -

1 University of California, Berkeley Fall Semester 2007 Department of Economics Professor George A. Akerlof Professor Maurice O

University of California, Berkeley Fall Semester 2007 Department of Economics Professor George A. Akerlof Professor Maurice Obstfeld ECONOMICS 202A READING LIST Textbook: David Romer, Advanced Macroeconomics, Third Edition. McGraw-Hill, 2005. I. A. Introduction/Overview of Course *George Akerlof, "The Missing Motivation in Macroeconomics," American Economic Review, March 2007, pp. 5-36. B. Introduction/Mathematical Review *Andrew C. Harvey, Time Series Models, Chapter 1, pp. 1-9; Ch. 2, pp. 21-53. David Romer, Third Edition, Chapter 5, "Traditional Keynesian Theories of Fluctuations," Sections 5.1 and 5.3-5.6, pp. 222-231, and 242-270. Maurice Obstfeld, “Dynamic Optimization in Continuous-Time Models (A Guide for the Perplexed),” manuscript, UC Berkeley, April 1992. Available at: http://www.econ.berkeley.edu/~obstfeld/ftp/perplexed/cts4a.pdf II. Equilibrium Concepts *David Romer, Third Edition, Chapter 6, "Microeconomic Foundations of Incomplete Nominal Adjustment," Sections 6.1-6.3, and 6.9-6.10, pp. 271-285, pp. 316-326. *Robert Lucas and Thomas Sargent, "After Keynesian Macroeconomics," from Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, After the Phillips Curve: Persistence of High Inflation and High Unemployment, Conference Series No. 19. *Thomas Sargent, "Rational Expectations, the Real Rate of Interest, and the Natural Rate of Unemployment," Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 1973:2, pp. 429-472. *John Taylor, "Staggered Wage Setting in a Macro Model," American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings, May 1979, pp. 108-113. Stanley Fischer, "Long-Term Contracts, Rational Expectations and the Optimal Money Supply Rate," Journal of Political Economy, February 1977, pp. 191-205. Laurence Ball, "Credible Disinflation with Staggered Price Setting," American Economic Review, March, 1994, pp. -

On Falling Neutral Real Rates, Fiscal Policy, and the Risk of Secular Stagnation

BPEA Conference Drafts, March 7–8, 2019 On Falling Neutral Real Rates, Fiscal Policy, and the Risk of Secular Stagnation Łukasz Rachel, LSE and Bank of England Lawrence H. Summers, Harvard University Conflict of Interest Disclosure: Lukasz Rachel is a senior economist at the Bank of England and a PhD candidate at the London School of Economics. Lawrence Summers is the Charles W. Eliot Professor and President Emeritus at Harvard University. Beyond these affiliations, the authors did not receive financial support from any firm or person for this paper or from any firm or person with a financial or political interest in this paper. They are currently not officers, directors, or board members of any organization with an interest in this paper. No outside party had the right to review this paper before circulation. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors, and do not necessarily reflect those of the Bank of England, the London School of Economics, or Harvard University. On falling neutral real rates, fiscal policy, and the risk of secular stagnation∗ Łukasz Rachel Lawrence H. Summers LSE and Bank of England Harvard March 4, 2019 Abstract This paper demonstrates that neutral real interest rates would have declined by far more than what has been observed in the industrial world and would in all likelihood be significantly negative but for offsetting fiscal policies over the last generation. We start by arguing that neutral real interest rates are best estimated for the block of all industrial economies given capital mobility between them and relatively limited fluctuations in their collective current account. -

Unemployment and Other Challenges. on the Nobel Prize in Economics Awarded to Peter A

CONTRIBUTIONS to SCIENCE, 7 (2): 163–170 (2011) Institut d’Estudis Catalans, Barcelona DOI: 10.2436/20.7010.01.122 ISSN: 1575-6343 The Nobel Prizes 2010 www.cat-science.cat Unemployment and other challenges. On the Nobel Prize in Economics awarded to Peter A. Diamond, Dale T. Mortensen and Christopher A. Pissarides* Joan Tugores Ques Department of Economic Theory, Faculty of Economics and Business, University of Barcelona, Barcelona Resum. Les contribucions del guanyadors del Premi Nobel Abstract. The contributions by the 2010 Nobel Prize winners d’Economia 2010 destaquen en els exàmens de la funció de in Economics stand out in examinations of the role of frictions les friccions en els diferents mercats, en què les heterogeneï- in different markets, in which heterogeneities and specificities tats i especificitats fan que sigui necessari un procés de recer- make a search process necessary in order to find a reasonable ca per a trobar una coincidència raonable entre les parts en match between the parties in a transaction. The applications to una transacció. Les aplicacions per als mercats de treball són labor markets are noteworthy, with major implications for the dignes de menció, amb grans implicacions per als determi- determinants of employment and unemployment, and for poli- nants de l’ocupació i l’atur i per a les polítiques en aquesta cies on these matters. However, the findings can also be ex- matèria. No obstant això, els resultats també es poden extra- trapolated to other kinds of markets and applications. polar a altres tipus -

Is the Great Recession Really Over? Longitudinal Evidence of Enduring Employment Impacts∗

Is the Great Recession Really Over? Longitudinal Evidence of Enduring Employment Impacts∗ Danny Yagan UC Berkeley and NBER November 2016 Abstract The severity of the Great Recession varied across U.S. local areas. Comparing two mil- lion workers within firms across space, I find that starting the recession in a below-median 2007-2009-employment-shock area caused workers to be 1.0 percentage points less likely to be employed in 2014, relative to starting the recession elsewhere. This enduring impact holds even when controlling for current local unemployment rates, which have converged across space. The results reject secular nationwide skill-biased shocks like exogenous tech- nical change as a full explanation for persistent post-2007 employment declines. Instead, the recession and its underlying causes depressed labor force participation and employ- ment even after unemployment returned to normal. ∗Email: [email protected]. The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Internal Revenue Service or the U.S. Treasury Department. This work is a component of a larger project examining the effects of tax expenditures on the budget deficit and economic activity; all results based on tax data in this paper are constructed using statistics in the updated November 2013 SOI Working Paper The Home Mortgage Interest Deduction and Migratory Insurance over the Great Recession, approved under IRS contract TIRNO-12-P-00374 and presented at the National Tax Association. I thank David Autor, David Card, Raj Chetty, Brad DeLong, Rebecca Diamond, Robert Hall, Hilary Hoynes, Erik Hurst, Lawrence Katz, Amir Kermani, Patrick Kline, Emi Nakamura, Matthew Notowidigdo, Evan K. -

Peter A. Diamond

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE PETER DIAMOND provided by Research Papers in Economics My grandparents immigrated to the U.S. around the turn of the last cen- tury. My mother’s parents and six older siblings came from Poland. My fa- ther’s parents met in New York, she having come from Russia and he from Romania. My parents, both born in 1908, grew up in New York and never lived outside the metropolitan area. Both finished high school and went to work, my father studying at Brooklyn Law School at night while selling shoes during the day. When they married in 1929, my mother was earning $15 a week as a bookkeeper and my father, $5 a week as a novice lawyer. My brother, Richard, was born in 1934 and I in 1940. My father continued to practice law until his late 80s, but my mother had left the paid labor force by the time of my birth. She volunteered in a number of organizations after that, often serving as treasurer, drawing on her bookkeeper background. In more recent times, with better opportunities for women, she would have had a good career. I started public school in the Bronx, and switched to suburban public Figure 1. Diamond with older brother Richard and parents, summer, 1944, Battle Creek Michigan, where his father was stationed. 303 Diamond_biog_.indd 3 2011-08-29 10:31:48 schools in second grade when the family moved to Woodmere, on Long Island. Our house faced the Long Island Rail Road and was so close to the tracks that the family thought the first train at 5 AM was coming through the bedrooms. -

Ideological Profiles of the Economics Laureates · Econ Journal Watch

Discuss this article at Journaltalk: http://journaltalk.net/articles/5811 ECON JOURNAL WATCH 10(3) September 2013: 255-682 Ideological Profiles of the Economics Laureates LINK TO ABSTRACT This document contains ideological profiles of the 71 Nobel laureates in economics, 1969–2012. It is the chief part of the project called “Ideological Migration of the Economics Laureates,” presented in the September 2013 issue of Econ Journal Watch. A formal table of contents for this document begins on the next page. The document can also be navigated by clicking on a laureate’s name in the table below to jump to his or her profile (and at the bottom of every page there is a link back to this navigation table). Navigation Table Akerlof Allais Arrow Aumann Becker Buchanan Coase Debreu Diamond Engle Fogel Friedman Frisch Granger Haavelmo Harsanyi Hayek Heckman Hicks Hurwicz Kahneman Kantorovich Klein Koopmans Krugman Kuznets Kydland Leontief Lewis Lucas Markowitz Maskin McFadden Meade Merton Miller Mirrlees Modigliani Mortensen Mundell Myerson Myrdal Nash North Ohlin Ostrom Phelps Pissarides Prescott Roth Samuelson Sargent Schelling Scholes Schultz Selten Sen Shapley Sharpe Simon Sims Smith Solow Spence Stigler Stiglitz Stone Tinbergen Tobin Vickrey Williamson jump to navigation table 255 VOLUME 10, NUMBER 3, SEPTEMBER 2013 ECON JOURNAL WATCH George A. Akerlof by Daniel B. Klein, Ryan Daza, and Hannah Mead 258-264 Maurice Allais by Daniel B. Klein, Ryan Daza, and Hannah Mead 264-267 Kenneth J. Arrow by Daniel B. Klein 268-281 Robert J. Aumann by Daniel B. Klein, Ryan Daza, and Hannah Mead 281-284 Gary S. Becker by Daniel B. -

Download Full Brief

OCTOBER 2005, NUMBER 35 WHY DO WOMEN CLAIM SOCIAL SECURITY BENEFITS SO EARLY? BY ALICIA H. MUNNELL AND MAURICIO SOTO* Introduction If individuals continue to withdraw completely from This brief summarizes the incentives facing older the labor force in their early 60s, a large and growing women when claiming their Social Security benefits. number will be hard pressed to maintain an adequate The analysis shows that single women and married standard of living throughout retirement. Economic women face very different choices. For most married and demographic pressures are gradually eroding key women, the Social Security benefit structure actually sources of retirement income at the same time that encourages them to grab their benefits as soon as pos- increases in life expectancy mean that people can sible. These incentives reinforce the tendency for expect to live for 20 years, on average, after they stop wives, who are usually younger, to retire when their working. And averages do not tell the whole story. husbands do. Early claiming may maximize the wife's Nearly one third of women and almost one fifth of Social Security "wealth," but it also encourages them men will live into their 90s. to stop working, creating a loss of earnings and 401(k) savings and extending the period over which they need Women's low wages, interrupted work histories, and support in retirement. role as caregivers make them especially vulnerable in old age. A solution to the income security challenge, Early Claiming of Social Security with a potentially enormous payoff, is for women to Benefits work longer. One important benefit of continued employment — in addition to increasing current income, allowing additional 401(k) contributions, and The existence of Social Security's Earliest Eligibility postponing the drawdown of savings — is avoiding the Age (EEA) means that most Americans have an impor- actuarial reduction, or enjoying the actuarial increase, tant choice to make once they turn age 62: claim in Social Security benefits. -

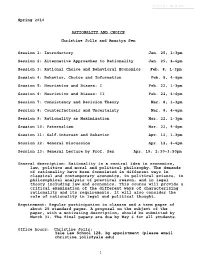

Rationality and Choice

Spring 2010 RATIONALITY AND CHOICE Christine Jolls and Amartya Sen Session 1: Introductory Jan. 25, 1-3pm Session 2: Alternative Approaches to Rationality Jan. 25, 4-6pm Session 3: Rational Choice and Behavioral Economics Feb. 8, 1-3pm Session 4: Behavior, Choice and Information Feb. 8, 4-6pm Session 5: Heuristics and Biases: I Feb. 22, 1-3pm Session 6: Heuristics and Biases: II Feb. 22, 4-6pm Session 7: Consistency and Decision Theory Mar. 8, 1-3pm Session 8: Counterfactuals and Uncertainty Mar. 8, 4-6pm Session 9: Rationality as Maximization Mar. 22, 1-3pm Session 10: Paternalism Mar. 22, 4-6pm Session 11: Self-interest and Behavior Apr. 12, 1-3pm Session 12: General Discussion Apr. 12, 4-6pm Session 13: General Lecture by Prof. Sen Apr. 19, 2:30-3:50pm General description: Rationality is a central idea in economics, law, politics and moral and political philosophy. The demands of rationality have been formulated in different ways in classical and contemporary economics, in political science, in philosophical analysis of practical reason, and in legal theory including law and economics. This course will provide a critical examination of the different ways of characterizing rationality and its requirements. It will also consider the role of rationality in legal and political thought. Requirement: Regular participation in classes and a term paper of about 25 standard pages. A proposal on the subject of the paper, with a motivating description, should be submitted by March 31. The final papers are due by May 6 for all students. Office hours: Christine Jolls: Yale Law School 128, by appointment (please email [email protected]) 1 Amartya Sen: Mondays 11-12, Littauer Center 205, no appointment needed Tuesdays 11-12, Littauer Center 205, by appointment (please call 5-1871) General readings: The following books may be used as general reference: Richard Thaler, Quasi Rational Economics.