INTRODUCTION John Lagerwey and Marc Kalinowski Over the Course Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chinese Civilization

Chinese Civilization PREHISTORY Sources for the earliest history Until recently we were dependent for the beginnings of Chinese history on the written Chinese tradition. According to these sources China's history began either about 4000 B.C. or about 2700 B.C. with a succession of wise emperors who "invented" the elements of a civilization, such as clothing, the preparation of food, marriage, and a state system; they instructed their people in these things, and so brought China, as early as in the third millennium B.C., to an astonishingly high cultural level. However, all we know of the origin of civilizations makes this of itself entirely improbable; no other civilization in the world originated in any such way. As time went on, Chinese historians found more and more to say about primeval times. All these narratives were collected in the great imperial history that appeared at the beginning of the Manchu epoch. That book was translated into French, and all the works written in Western languages until recent years on Chinese history and civilization have been based in the last resort on that translation. The Peking Man Man makes his appearance in the Far East at a time when remains in other parts of the world are very rare and are disputed. He appears as the so-called "Peking Man", whose bones were found in caves of Chou-k'ou-tien south of Peking. The Peking Man is vastly different from the men of today, and forms a special branch of the human race, closely allied to the Pithecanthropus of Java. -

Inscriptional Records of the Western Zhou

INSCRIPTIONAL RECORDS OF THE WESTERN ZHOU Robert Eno Fall 2012 Note to Readers The translations in these pages cannot be considered scholarly. They were originally prepared in early 1988, under stringent time pressures, specifically for teaching use that term. Although I modified them sporadically between that time and 2012, my final year of teaching, their purpose as course materials, used in a week-long classroom exercise for undergraduate students in an early China history survey, did not warrant the type of robust academic apparatus that a scholarly edition would have required. Since no broad anthology of translations of bronze inscriptions was generally available, I have, since the late 1990s, made updated versions of this resource available online for use by teachers and students generally. As freely available materials, they may still be of use. However, as specialists have been aware all along, there are many imperfections in these translations, and I want to make sure that readers are aware that there is now a scholarly alternative, published last month: A Source Book of Ancient Chinese Bronze Inscriptions, edited by Constance Cook and Paul Goldin (Berkeley: Society for the Study of Early China, 2016). The “Source Book” includes translations of over one hundred inscriptions, prepared by ten contributors. I have chosen not to revise the materials here in light of this new resource, even in the case of a few items in the “Source Book” that were contributed by me, because a piecemeal revision seemed unhelpful, and I am now too distant from research on Western Zhou bronzes to undertake a more extensive one. -

Chinax Transcript Week 3--Legitimation of Power in Antiquity

ChinaX Transcript Week 3--Legitimation of Power in Antiquity Historical Overview: The Chinese Bronze Age Following these great sages were the first three Chinese dynasties-- the Xia, Shang, and Zhou. Much debate has arisen around whether or not the Xia dynasty was an actual historical reality or just a later myth. While no writing has been archaeologically discovered confirming the existence of the Xia, sites such as Erlitou reveal that a large state was present at the beginning of the Bronze Age in the central plains -- that is, at roughly the same time and in the same area as the Xia is recorded in later texts. The Shang dynasty is the first Chinese dynasty that is historically attested. While the exact dates for this dynasty are uncertain, it is believed to have lasted from the 17th to the 11th century BCE. According to later legends, the last Xia ruler, Jie, was a cruel, lascivious tyrant. And thus, Tang, the first Shang king, arose and overthrew him, founding the new Shang dynasty. The Shang are said to have ruled for many centuries, though the most dramatic archaeological discoveries of Shang remains date to the final portion of their reign at their last capital of Yin. Thus, the Shang is sometimes referred to as Yin. Near Anyang in Henan at a site called Yinxu, which actually means today the ruins of Yin, archaeologists have discovered here royal tombs with bronze ritual vessels, massive palaces, and workshops, and most importantly, animal bones inscribed with divination charges. Using these inscriptions, scholars have been able to verify that this site did indeed belong to the Shang we read of in ancient texts, and moreover, reconstruct how the final Shang kings lived and ruled. -

The Emergence of the Wen/Wu Problem

Chapter 1 The Emergence of the Wen/Wu Problem The dominance of the civil over the martial in most Chinese historical and philosophical texts of the imperial era has tended to obscure the essential importance of wu in the Sinitic (Huaxia 厗⢷) realm during the pre-Qin period. In the compiling of China’s standard histories (zhengshi 㬋⎚), for example, military affairs were largely restricted to incidental treatment in the basic annals (benji 㛔䲨) and biographical accounts (liezhuan ↿⁛), and garnered only uneven coverage in the treatises (shu 㚠 or zhi ⽿). Generally speaking, if military matters were considered at all in the official accounts of Chinese regimes, institutional evolution and penal administration were the principal interests of traditional scholars, not the broader significance of martiality in Chinese culture and society.1 And yet, as shown in the Hanshu “Treatise on Literature,” there was a sizable and diversified stratum of general and specialized works in the Han and pre-Han eras dealing wholly or in part with martial affairs as an ingredient of government policy and intellectual discourse. The volume of these titles bespeaks keen interest in the early imperial era and before in resolving a set of compelling sociopolitical, philosophical, and practical questions centered on martiality and its proper relation to civility—that is, the wen/wu problem. This chapter will explore the conditions that led initially to the consideration of this problem and the major solutions proposed to resolve the issue in the pre-Han period. The Achievement of Balance Repeatedly one finds in pre-Qin writings the notion that war is a natural, evolving attribute of the human community, and that martial activity allowed, paradoxically, for the advancement of civilized life. -

Social Studies Enrichment Packet Plouffe Academy Ancient China

Social Studies Enrichment Packet Plouffe Academy Ancient China 1 Adapted from Learning Outcomes Language Objectives – The student will… use past tense verbs in English correctly to describe the historic events and impact of the ancient Chinese dynasties. use descriptive adjectives, including those to describe color, age, size and distance to describe the geography, innovations and trade of ancient China. Content Objectives – use specific examples to describe in English how the physical geography of China presented ancient people with challenges. identify at least three ways that the geography of China influenced the way ancient people lived explain the major beliefs of Confucianism, Taoism and Legalism, founders, and influence on ancient Chinese government. name at least two major accomplishments of each of the Shang, Zhou, Qin, and Han dynasties. identify the purpose of the Silk Road and describe how cultural diffusion took place because of its existence. analyze why the Great Wall of China was built and if was it necessary? Key Vocabulary Terms: dynasty warlord aristocracy periphery bureaucracy plateau emperor nomad Confucianism terrain Taoism mandate Terracotta Army Ying and Yang Legalism Sentry Great Wall permeated basin 2 Adapted from Exploring the Geography of Ancient China Today, China is the third-largest country in the world. Third in land size to only Russia and Canada, China has close to four million square miles of land. To its north, China is bordered by Mongolia and Russia. Kazakhstan and Krygzstan share China’s western border, and its southern neighbors include India, Nepal, Burma, and Vietnam. In 1990, China’s population hovered slightly over 1 billion people, but by the year 2025, China is expected to have over 1.5 billion. -

UC San Diego UC San Diego Previously Published Works

UC San Diego UC San Diego Previously Published Works Title An Outline History of East Asia to 1200, second edition Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9d699767 Author Schneewind, Sarah Publication Date 2021-06-01 Supplemental Material https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9d699767#supplemental eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Second Edition An O utline H istory of Ea st A sia to 1200 b y S a r a h S c h n e e w i n d Second Edition An Outline History of East Asia to 1200 by S ar ah S chneewi nd Introduction This is the second edition of a textbook that arose out of a course at the University of California, San Diego, called HILD 10: East Asia: The Great Tradition. The course covers what have become two Chinas, Japan, and two Koreas from roughly 1200 BC to about AD 1200. As we say every Fall in HILD 10: “2400 years, three countries, ten weeks, no problem.” The book does not stand alone: the teacher should assign primary and secondary sources, study questions, dates to be memorized, etc. The maps mostly use the same template to enable students to compare them one to the next. About the Images and Production Labor The Cover This image represents a demon. It comes from a manuscript on silk that explains particular demons, and gives astronomical and astrological information. The manuscript was found in a tomb from the southern mainland state of Chu that dates to about 300 BC. I chose it to represent how the three countries of East Asia differ, but share a great deal and grew up together. -

The Rite of Yinzhi (Drinking Celebration) and Poems Recorded on the Tsinghua Bamboo Slips 清華簡中所見古飲至禮及古佚詩試解

The Rite of Yinzhi (Drinking Celebration) and Poems Recorded on the Tsinghua Bamboo Slips 清華簡中所見古飲至禮及古佚詩試解 Chen Zhi This paper is based on a series of articles regarding the Tsinghua bamboo slip (hereafter TBS) texts published on Wen wu and Guangming daily from late 2008 to August 2009.1 Although not intended for specialists, Li Xueqin’s 李學勤 article on August 4th, 2009 introduces a TBS text entitled “Qi du” 耆( )夜, which details a wine celebration immediately after King Wu’s military campaign against the state of Li 黎 in the eighth year of his reign.2 The conquest of the state of Li, alternatively written as qi 耆, as stated in the chapter “Xi Bo kan Li” 西伯戡黎 of Old-text Shangshu was traditionally attributed to King Wen.3 According to Li Xueqin, the bamboo text records of the wine celebration after the conquest of the state of Li called together many leading figures in early Zhou history, such as the duke of Zhou 1 In writing this paper, I have consulted Chutu Wenxian Yanjiu yu Baohuzhongxin jianbao 出土文獻研究與保護中心簡報, No. 1(15 December 2008):2-21, which contains six reports regarding the discovery, content and significance of the TBS: Xie Weihe 謝維和, “Fakanci” 發刊詞, 2; “Qinghua Daxue rucang Zhanguo zhujian” 清 華大學入藏戰國竹簡, 3-4; “Qinghua Daxue suocang zhujian jiandinghui jianding yijian” 清華大學所藏竹簡鑒定意見, 4-5; Li Xueqin, “Chushi Qinghuajian” 初識清 華簡, 7-10; Zhao Guifang 趙桂芳, “Qinghua Daxue rucang baoshuijian de qingxi yu baohu” 清華大學入藏飽水簡的清洗與保護, 11-12; Shen Jianhua 沈建華, “ Kongbi zhong shu yu Jizhong jinian” 孔壁中書與汲塚紀年, 12-15. I also consulted the following reports and articles: Li Xueqin 李學勤, “Qinghuajian yanjiu chujian chengguo: jiedu Zhou Wenwang yiyan” 清華簡研究初見成果:解讀周文王 遺言, Guangming dayily, 13 April 2009; “Qinghuajian Baoxun zhong de jige wenti” 清華簡保訓的幾個問題, Wen wu, 6, 2009:77; Li Xueqin 李學勤, “Qinghuajian Qi du” 清華簡 夜, Guangming Daily, 3 August 2009. -

China Is a Country in East Asia Whose Culture Is Considered the Oldest, Still Extant, in the World

China is a country in East Asia whose culture is considered the oldest, still extant, in the world. The name `China’ comes from the Sanskrit Cina (derived from the name of the Chinese Qin Dynasty, pronounced `Chin’) which was translated as `Cin’ by the Persians and seems to have become popularized through trade along the Silk Road from China to the rest of the world. The Romans and the Greeks knew the country as `Seres’, “the land where silk comes from”. The name `China’ does not appear in print in the west until 1516 CE in Barbosa’s journals narrating his travels in the east (though the Europeans had long known of China through trade via the Silk Road). Marco Polo, the famous explorer who familiarized China to Europe in the 13th century CE, referred to the land as `Cathay’. In Mandarin Chinese, the country is known as `Zhongguo” meaning `central state’ or `middle empire’. Well before the advent of recognizable civilization in the region, the land was occupied by hominids. Peking Man, a skull fossil discovered in 1927 CE near Beijing, lived in the area between 700,000 to 200,000 years ago and Yuanmou Man, whose remains were found in Yuanmou in 1965 CE, inhabited the land 1.7 million years ago. Evidence uncovered with these finds shows that these early inhabitants knew how to fashion stone tools and use fire. While it is commonly accepted that human beings originated in Africa and then migrated to other points around the globe, China’s paleoanthropologists “support the theory of `regional evolution’ of the origin of man” (China.org) which claims an independent basis for the birth of mankind. -

Four Topics in Archaeological Chronology Zhang Chi, Annie Chan

Translation: Four Topics in Archaeological Chronology Zhang Chi, Annie Chan To cite this version: Zhang Chi, Annie Chan. Translation: Four Topics in Archaeological Chronology. Chinese Cultural Relics, Eastview Press, 2016. hal-03221001 HAL Id: hal-03221001 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03221001 Submitted on 10 May 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Research and Exploration Four Topics in Archaeological Chronology* Chi Zhang 张弛 Professor, School of Archaeology and Museology, Peking University * he introduction of archaeological solute dating and cross-dating, the last of which is the chronology is one of the founda- combined use of the two preceding types of dating, tions of contemporary archaeology. have been a part of archaeological chronology. Thus The evolutionary theories of early far, apart from such minute improvements as the cali- Tcontemporary archaeology and the study of cultural bration of radiocarbon dates with dendrochronology history adopt the relative chronology established by and the introduction of AMS dating, little progress stratigraphy and seriation as the chronological basis has been made in these two types of dating compared for constructing the most fundamental framework of to the rapid development of many other methods human prehistory. -

On the Round Burial Pit of the Yin Period at Hougang, Anyang

Chinese Archaeology 11 (2011): 155–159 © 2011 by Walter de Gruyter, Inc.· Boston · Berlin. DOI 10.1515/CHAR–2011–019 On the round burial pit of the Yin Period at Hougang, Anyang Jinpeng Du* a specially produced pit. The deposits in the pit can be divided into five layers. * Institute of Archaeology, Chinese Academy of Social The first, about 0.9m thick, was that of red burnt clay Sciences, Beijing 100710 clods piled up randomly. Sherds of pottery li-cauldrons and jars of the Yin Period accompanied this layer; they Abstract could not be restored. The second layer ranging from 0.35 to 0.6m thick was composed of dark gray earth; In the light of the unearthed objects and stratigraphic it contained numerous lumps and grains of charcoal, relations, it can be inferred that the round burial pit as well as burnt bones, clamshells, etc. A few human (HGH10) of the Yin period at Hougang, Anyang, was bones were discovered underneath this layer; these were formed in the late Yin or at the turn from the Yin to the the uppermost layer of human remains. The third layer, Zhou period. The dead buried in the pit were seriously 0.3–0.5m thick, was of grayish-yellow earth mixed with maimed or even beheaded and their skeletons were in sparse grains of charcoal and burnt earth. It contained an extraordinary position and in disorder. However, they large numbers of potsherds, forming a layer of ceramic were offered large-sized bronze ritual vessels and a great fragments ranging from 0.15 to 0.25m thick. -

Applied Field-Allocation Astrology in Zhou China: Duke Wen of Jin and the Battle of Chengpu (632 B. C.) Author(S): David W

Applied Field-Allocation Astrology in Zhou China: Duke Wen of Jin and the Battle of Chengpu (632 B. C.) Author(s): David W. Pankenier Source: Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 119, No. 2 (Apr. - Jun., 1999), pp. 261- 279 Published by: American Oriental Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/606110 Accessed: 23/03/2010 21:23 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=aos. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. American Oriental Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of the American Oriental Society. -

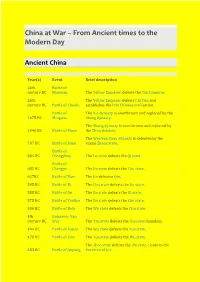

China at War – from Ancient Times to the Modern Day

China at War – From Ancient times to the Modern Day Ancient China Year(s) Event Brief description 26th Battle of century BC Banquan The Yellow Emperor defeats the Yan Emperor. 26th The Yellow Emperor defeats Chi You and century BC Battle of Zhuolu establishes the Han Chinese civilisation. Battle of The Xia dynasty is overthrown and replaced by the 1675 BC Mingtiao Shang dynasty. The Shang dynasty is overthrown and replaced by 1046 BC Battle of Muye the Zhou dynasty. The Western Zhou dynasty is defeated by the 707 BC Battle of Xuge vassal Zheng state. Battle of 684 BC Changshao The Lu state defeats the Qi state Battle of 632 BC Chengpu The Jin state defeats the Chu state. 627BC Battle of Xiao The Jin defeates Qin. 595 BC Battle of Bi The Chu state defeats the Jin state. 588 BC Battle of An The Jin state defeats the Qi state. 575 BC Battle of Yanling The Jin state defeats the Chu state. 506 BC Battle of Boju The Wu state defeats the Chu state. 4th Gojoseon–Yan century BC War The Yan state defeats the Gojoseon kingdom. 494 BC Battle of Fujiao The Wu state defeats the Yue state. 478 BC Battle of Lize The Yue state defeats the Wu state. The Zhao state defeats the Zhi state. Leads to the 453 BC Battle of Jinyang Partition of Jin. 353 BC Battle of Guiling The Qi state defeats the Wei state. 342 BC Battle of Maling The Qi state defeats the Wei state. Battle of 341 BC Guailing 293 BC Battle of Yique The Qin state defeats the Wei and Han states.