The Rite of Yinzhi (Drinking Celebration) and Poems Recorded on the Tsinghua Bamboo Slips 清華簡中所見古飲至禮及古佚詩試解

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chinese Civilization

Chinese Civilization PREHISTORY Sources for the earliest history Until recently we were dependent for the beginnings of Chinese history on the written Chinese tradition. According to these sources China's history began either about 4000 B.C. or about 2700 B.C. with a succession of wise emperors who "invented" the elements of a civilization, such as clothing, the preparation of food, marriage, and a state system; they instructed their people in these things, and so brought China, as early as in the third millennium B.C., to an astonishingly high cultural level. However, all we know of the origin of civilizations makes this of itself entirely improbable; no other civilization in the world originated in any such way. As time went on, Chinese historians found more and more to say about primeval times. All these narratives were collected in the great imperial history that appeared at the beginning of the Manchu epoch. That book was translated into French, and all the works written in Western languages until recent years on Chinese history and civilization have been based in the last resort on that translation. The Peking Man Man makes his appearance in the Far East at a time when remains in other parts of the world are very rare and are disputed. He appears as the so-called "Peking Man", whose bones were found in caves of Chou-k'ou-tien south of Peking. The Peking Man is vastly different from the men of today, and forms a special branch of the human race, closely allied to the Pithecanthropus of Java. -

The Evolution of Mathematics in Ancient China: from the Newly Discovered Shu and Suan Shu Shu Bamboo Texts to the Nine Chapters

The Evolution of Mathematics in Ancient China: From the Newly Discovered Shu and Suan shu shu Bamboo Texts to the Nine Chapters on the Art of Mathematics*,† by Joseph W. Dauben‡ The history of ancient Chinese mathematics and texts currently being conserved and studied at its applications has been greatly stimulated in Tsinghua University and Peking University in Beijing, the past few decades by remarkable archaeological the Yuelu Academy in Changsha, and the Hubei discoveries of texts from the pre-Qin and later Museum in Wuhan, it is possible to shed new light periods that for the first time make it possible to on the history of early mathematical thought and its study in detail mathematical material from the time applications in ancient China. Also discussed here are at which it was written. By examining the recent developments of new techniques and justifications Warring States, Qin, and Han bamboo mathematical given for the problems that were a significant part of the growing mathematical corpus, and which * © 2014 Joseph W. Dauben. Used with permission. eventually culminated in the comprehensive Nine † This article is based on a lecture presented in September of 2012 at the Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies at Har- Chapters on the Art of Mathematics. vard University, which was based on a lecture first given at National Taiwan Tsinghua University (Hsinchu, Taiwan) in the Spring of 2012. I am grateful to Thomas Lee of National Chiaotung University of Taiwan where I spent the academic Contents year 2012 as Visiting Research Professor at Chiaota’s Insti- tute for Humanities and Social Sciences, which provided sup- 1 Recent Archaeological Excavations: The Shu port for much of the research reported here, and to Shuchun and Suan shu shu ................ -

Pimsleur Mandarin Course I Vocabulary 对不起: Dui(4) Bu(4) Qi(3)

Pimsleur Mandarin Course I vocabulary 对不起 : dui(4) bu(4) qi(3) excuse me; beg your pardon 请 : qing(3) please (polite) 问 : wen(4) ask; 你 : ni(3) you; yourself 会 : hui(4) can 说 : shuo(1) speak; talk 英文 : ying(1) wen(2) English(language) 不会 : bu(4) hui(4) be unable; can not 我 : wo(3) I; myself 一点儿 : yi(1) dian(3) er(2) a little bit 美国人 : mei(3) guo(2) ren(2) American(person); American(people) 是 : shi(4) be 你好 ni(2) hao(3) how are you 普通话 : pu(3) tong(1) hua(4) Mandarin (common language) 不好 : bu(4) hao(3) not good 很好 : hen(3) hao(3) very good 谢谢 : xie(4) xie(4) thank you 人 : ren(2) person; 可是 : ke(3) shi(4) but; however 请问 : qing(3) wen(4) one should like to ask 路 : lu(4) road 学院 : xue(2) yuan(4) college; 在 : zai(4) at; exist 哪儿 : na(3) er(2) where 那儿 na(4) er(2) there 街 : jie(1) street 这儿 : zhe(4) er(2) here 明白 : ming(2) bai(2) understand 什么 : shen(2) me what 中国人 : zhong(1) guo(2) ren(2) Chinese(person); Chinese(people) 想 : xiang(3) consider; want to 吃 : chi(1) eat 东西 : dong(1) xi(1) thing; creature 也 : ye(3) also 喝 : he(1) drink 去 : qu(4) go 时候 : shi(2) hou(4) (a point in) time 现在 : xian(4) zai(4) now 一会儿 : yi(1) hui(4) er(2) a little while 不 : bu(4) not; no 咖啡: ka(1) fei(1) coffee 小姐 : xiao(3) jie(3) miss; young lady 王 wang(2) a surname; king 茶 : cha(2) tea 两杯 : liang(3) bei(1) two cups of 要 : yao(4) want; ask for 做 : zuo(4) do; make 午饭 : wu(3) fan(4) lunch 一起 : yi(1) qi(3) together 北京 : bei(3) jing(1) Beijing; Peking 饭店 : fan(4) dian(4) hotel; restaurant 点钟 : dian(3) zhong(1) o'clock 几 : ji(1) how many; several 几点钟? ji(1) dian(3) zhong(1) what time? 八 : ba(1) eight 啤酒 : pi(2) jiu(3) beer 九 : jiu(3) understand 一 : yi(1) one 二 : er(4) two 三 : san(1) three 四 : si(4) four 五 : wu(3) five 六 : liu(4) six 七 : qi(1) seven 八 : ba(1) eight 九 : jiu(3) nine 十 : shi(2) ten 不行: bu(4) xing(2) won't do; be not good 那么 : na(3) me in that way; so 跟...一起 : gen(1)...yi(1) qi(3) with .. -

Inscriptional Records of the Western Zhou

INSCRIPTIONAL RECORDS OF THE WESTERN ZHOU Robert Eno Fall 2012 Note to Readers The translations in these pages cannot be considered scholarly. They were originally prepared in early 1988, under stringent time pressures, specifically for teaching use that term. Although I modified them sporadically between that time and 2012, my final year of teaching, their purpose as course materials, used in a week-long classroom exercise for undergraduate students in an early China history survey, did not warrant the type of robust academic apparatus that a scholarly edition would have required. Since no broad anthology of translations of bronze inscriptions was generally available, I have, since the late 1990s, made updated versions of this resource available online for use by teachers and students generally. As freely available materials, they may still be of use. However, as specialists have been aware all along, there are many imperfections in these translations, and I want to make sure that readers are aware that there is now a scholarly alternative, published last month: A Source Book of Ancient Chinese Bronze Inscriptions, edited by Constance Cook and Paul Goldin (Berkeley: Society for the Study of Early China, 2016). The “Source Book” includes translations of over one hundred inscriptions, prepared by ten contributors. I have chosen not to revise the materials here in light of this new resource, even in the case of a few items in the “Source Book” that were contributed by me, because a piecemeal revision seemed unhelpful, and I am now too distant from research on Western Zhou bronzes to undertake a more extensive one. -

Sunrise and Sunset Azimuths in the Planning of Ancient Chinese Towns Amelia Carolina Sparavigna

Sunrise and Sunset Azimuths in the Planning of Ancient Chinese Towns Amelia Carolina Sparavigna To cite this version: Amelia Carolina Sparavigna. Sunrise and Sunset Azimuths in the Planning of Ancient Chinese Towns. International Journal of Sciences, Alkhaer, UK, 2013, 2 (11), pp.52-59. 10.18483/ijSci.334. hal- 02264434 HAL Id: hal-02264434 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02264434 Submitted on 8 Aug 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 1Department of Applied Science and Technology, Politecnico di Torino, Italy Abstract: In the planning of some Chinese towns we can see an evident orientation with the cardinal direction north-south. However, other features reveal a possible orientation with the directions of sunrise and sunset on solstices too, as in the case of Shangdu (Xanadu), the summer capital of Kublai Khan. Here we discuss some other examples of a possible solar orientation in the planning of ancient towns. We will analyse the plans of Xi’an, Khanbalik and Dali. Keywords: Satellite Imagery, Orientation, Archaeoastronomy, China 1. Introduction different from a solar orientation with sunrise and Recently we have discussed a possible solar sunset directions. -

The Treatment of Constraint According to Applied Channel Theory 59

Journal of Chinese Medicine • Number 113 • February 2017 The Treatment of Constraint According to Applied Channel Theory 59 The Treatment of Constraint According to Applied Channel Theory Introduction us to the second important concept of Applied By: Wang Ju-yi Commonly-used concepts in Chinese medicine can Channel Theory - channel qi transformation. and be difficult to comprehend, not only for practitioners Channels are involved with the movement of the Jonathan W. who do not know the Chinese language, but also for body’s qi, blood and fluids. They govern the processes Chang those who are native speakers of Chinese. As the most of nourishment, metabolism, growth and eventual fundamental concepts of Chinese medicine originated decline of the viscera, orifices and tissues of the entire Keywords: over two thousand years ago, modern practitioners body. The channels are essential for controlling and Acupuncture, face an arduous task. In order to grasp these classical regulating the processes of absorption, metabolism Chinese concepts, Dr. Wang Ju-yi believes that we should try and transformation of qi, blood, fluids and nutrients. medicine, to understand how the ancient doctors perceived the All physiological and pathological processes involve applied channel world. To do this, Dr. Wang has developed the habit of qi transformation. It is important to note that each theory, channel researching the etymology of Chinese medical terms. channel has its unique physiology (discussed in palpation, By analysing their original meaning, we can come more detail later in this article) and when there is constraint, yu, to understand how classical physicians used these an impediment in channel physiology, an abnormal 郁, depression, terms to describe the physiological and pathological change will appear in the channel that can be physically stagnation phenomena they observed in their patients. -

The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2012 Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier Wai Kit Wicky Tse University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian History Commons, Asian Studies Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Tse, Wai Kit Wicky, "Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier" (2012). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 589. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/589 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/589 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier Abstract As a frontier region of the Qin-Han (221BCE-220CE) empire, the northwest was a new territory to the Chinese realm. Until the Later Han (25-220CE) times, some portions of the northwestern region had only been part of imperial soil for one hundred years. Its coalescence into the Chinese empire was a product of long-term expansion and conquest, which arguably defined the egionr 's military nature. Furthermore, in the harsh natural environment of the region, only tough people could survive, and unsurprisingly, the region fostered vigorous warriors. Mixed culture and multi-ethnicity featured prominently in this highly militarized frontier society, which contrasted sharply with the imperial center that promoted unified cultural values and stood in the way of a greater degree of transregional integration. As this project shows, it was the northwesterners who went through a process of political peripheralization during the Later Han times played a harbinger role of the disintegration of the empire and eventually led to the breakdown of the early imperial system in Chinese history. -

Social Mobility in China, 1645-2012: a Surname Study Yu (Max) Hao and Gregory Clark, University of California, Davis [email protected], [email protected] 11/6/2012

Social Mobility in China, 1645-2012: A Surname Study Yu (Max) Hao and Gregory Clark, University of California, Davis [email protected], [email protected] 11/6/2012 The dragon begets dragon, the phoenix begets phoenix, and the son of the rat digs holes in the ground (traditional saying). This paper estimates the rate of intergenerational social mobility in Late Imperial, Republican and Communist China by examining the changing social status of originally elite surnames over time. It finds much lower rates of mobility in all eras than previous studies have suggested, though there is some increase in mobility in the Republican and Communist eras. But even in the Communist era social mobility rates are much lower than are conventionally estimated for China, Scandinavia, the UK or USA. These findings are consistent with the hypotheses of Campbell and Lee (2011) of the importance of kin networks in the intergenerational transmission of status. But we argue more likely it reflects mainly a systematic tendency of standard mobility studies to overestimate rates of social mobility. This paper estimates intergenerational social mobility rates in China across three eras: the Late Imperial Era, 1644-1911, the Republican Era, 1912-49 and the Communist Era, 1949-2012. Was the economic stagnation of the late Qing era associated with low intergenerational mobility rates? Did the short lived Republic achieve greater social mobility after the demise of the centuries long Imperial exam system, and the creation of modern Westernized education? The exam system was abolished in 1905, just before the advent of the Republic. Exam titles brought high status, but taking the traditional exams required huge investment in a form of “human capital” that was unsuitable to modern growth (Yuchtman 2010). -

符傳孝SUN-HOO FOO. [email protected]

符傳孝 SUN-HOO FOO. [email protected] 1/11 Synopsis Fu2Shi4Zu2Pu3 This synopsis of 符氏族譜 (Fu2Shi4Zu2pu3) is edited from 101 volume of Family roots published in 1936 ,during that time a new generation poem of middle name was compiled to unified the 6 branches of FOO (FU) . It took more than 600 workers and 5 years to produce. This photo copy edition was produced in 1982 from a single set possessed by 符氏社 FOO TEE TAY ( CLAN TEMPLE) in Singapore.. After reading this article I hope you will have some understanding of the Foo (Fu) Chinese family. How Foo get their last name? When did it first acquire the name? What is a generation name? What is the meaning of generation name? And how do Foo decide to use which character as their generation name? How do members of the Foo family keep the same generation name after so many years? How many generations have passed since the first Foo? How do Chinese keep their ancestry? 2/11 Synopsis Fu2Shi4Zu2Pu3 3/11 Synopsis Fu2Shi4Zu2Pu3 Summary of the Foo ancester tree from 1-45 The text is roughly divided into the followings and tries to answer the questions posted. The beginning and history of 符(Fu2) Current generation names (Poem) and its Meanings. 4/11 Synopsis Fu2Shi4Zu2Pu3 The beginning of 符(Fu2) Artist ChitFu Yu, in this painting of You3chen2 and calligraphy, depict a brief history of FOO(Fu) . 有 辰 渡 琼 you3 chen2 du4 qiong2 YOU3 CHEN2 WENT ACROSS THE SEA TO THE HAINAN ISLAND(琼) 符 氏 始 於 雅 fu2 shi4 shi3 yu2 ya3 THE FOO ANCESTRY STARTS WITH YA。 雅 为 鲁 顷 公 孙 ya3 wei2 lu3 qing3 gong1 sun1 YA3 WAS THE GRANDSON OF QING3(顷), THE DUKE OF T HE COUNTRY LU3。 原 姬 姓 yuan2 ju1 xing4 ORIGINALLY HIS LAST NAME WAS JI. -

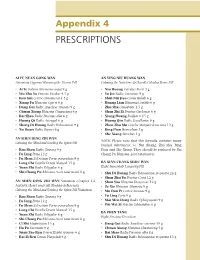

Appendix 4 PRESCRIPTIONS

Appendix 4 PRESCRIPTIONS AI FU NUAN GONG WAN AN YING NIU HUANG WAN Artemisia-Cyperus Warming the Uterus Pill Calming the Nutritive-Qi [Level] Calculus Bovis Pill • Ai Ye Folium Artemisiae argyi 9 g • Niu Huang Calculus Bovis 3 g • Wu Zhu Yu Fructus Evodiae 4.5 g • Yu Jin Radix Curcumae 9 g • Rou Gui Cortex Cinnamomi 4.5 g • Shui Niu Jiao Cornu Bubali 6 g • Xiang Fu Rhizoma Cyperi 9 g • Huang Lian Rhizoma Coptidis 6 g • Dang Gui Radix Angelicae sinensis 9 g • Zhu Sha Cinnabaris 1.5 g • Chuan Xiong Rhizoma Chuanxiong 6 g • Shan Zhi Zi Fructus Gardeniae 6 g • Bai Shao Radix Paeoniae alba 6 g • Xiong Huang Realgar 0.15 g • Huang Qi Radix Astragali 6 g • Huang Qin Radix Scutellariae 9 g • Sheng Di Huang Radix Rehmanniae 9 g • Zhen Zhu Mu Concha Margatiriferae usta 12 g • Xu Duan Radix Dipsaci 6 g • Bing Pian Borneolum 3 g • She Xiang Moschus 1 g AN SHEN DING ZHI WAN NOTE: Please note that this formula contains many Calming the Mind and Settling the Spirit Pill banned substances, i.e. Niu Huang, Zhu Sha, Bing • Ren Shen Radix Ginseng 9 g Pian and She Xiang. They should be replaced by Shi • Fu Ling Poria 12 g Chang Pu Rhizoma Acori tatarinowii. • Fu Shen Sclerotium Poriae pararadicis 9 g • Long Chi Fossilia Dentis Mastodi 15 g BA XIAN CHANG SHOU WAN • Yuan Zhi Radix Polygalae 6 g Eight Immortals Longevity Pill • Shi Chang Pu Rhizoma Acori tatarinowii 8 g • Shu Di Huang Radix Rehmanniae preparata 24 g • Shan Zhu Yu Fructus Corni 12 g AN SHEN DING ZHI WAN Variation (Chapter 14, • Shan Yao Rhizoma Dioscoreae 12 g Anxiety, Heart and Gall Bladder -

Joint Center for Soft Matter and Biological Physics and Condensed Matter Seminar Prof

Joint Center for Soft Matter and Biological Physics and Condensed Matter Seminar Prof. Qi-Huo Wei Department of Physics and Advanced Materials and Liquid Crystal Institute, Kent State University, Kent, OH “Printing Molecular Orientations as You Wish” Date/Time: Monday, 21 October 2019, 4:00pm -5:00pm Location: 304 Robeson Hall Abstract: Liquid crystals consisting of rod-shaped molecules are a remarkable soft matter with extraordinary responsivity to external stimuli. Techniques to control molecular orientations are essential in both making and operating liquid crystal devices that have changed our daily lives completely. Traditional display devices are based on uniform alignments of molecules at substrate surfaces. In this talk, I will present a new photopatterning approach for aligning molecules into complex 2D and 3D orientations with sub-micron resolutions. This approach relies on so-called plasmonic metamasks to generate designer polarization direction patterns and photoalignments. I will present the basic principles behind this approach and a number of intriguing applications enabled by it, including micro-optical devices for laser beam shaping, commanding chaotic motions of bacteria, and creating topological defects with designer structures. Qi-Huo Wei studied in the Physics Department at Nanjing University and got his PhD in condensed matter physics in 1993. He is currently a professor at the Advanced Material and Liquid Crystal Institute in Kent State University, USA. He made original contributions to the basic understanding of a diverse set of topics, including single-file diffusion, plasmonic coupling in nanoparticles, Brownian motion of low symmetry colloids, and photoalignment patterning of molecular orientations. He was an Alexander von Humboldt research fellow between 1996 and 1999 at University of Konstanz in Germany, and a recipient of the NSF CAREER award in 2011. -

Where Was the Western Zhou Capital? a Capital City Has a Special Status in Every Country

Maria Khayutina [email protected] Where Was the Western Zhou Capital? A capital city has a special status in every country. Normally, this is a political, economical, social center. Often it is a cultural and religious center as well. This is the place of governmental headquarters and of the residence of power-holding elite and professional administrative cadres. In the societies, where transportation means are not much developed, this is at the same time the place, where producers of the top quality goods for elite consumption live and work. A country is often identified with its capital city both by its inhabitants and the foreigners. Wherefore, it is hardly possible to talk about the history of a certain state without making clear, where was located its capital. The Chinese history contains many examples, when a ruling dynasty moved its capital due to defensive or other political reasons. Often this shift caused not only geographical reorganization of the territory, but also significant changes in power relations within the state, as well as between it and its neighbors. One of the first such shifts happened in 771 BC, when the heir apparent of the murdered King You 幽 could not push back invading 犬戎 Quanrong hordes from the nowadays western 陜西 Shaanxi province, but fled to the city of 成周 Chengzhou near modern 洛陽 Luoyang, where the royal court stayed until the fall of the 周 Zhou in the late III century BC. This event is usually perceived as a benchmark between the two epochs – the “Western” and “Eastern” Zhou respectively, distinctly distinguished one from another.