Cep-Cdcpp (2019) 17E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2009/2010

Federal Agency for the Prevention of Torture ANNUAL REPORT 2009 / 2010 Period under report 1 May 2009 – 30 April 2010 2 © Federal Agency for the Prevention of Torture All rights reserved Printed by: Druckerei Zeidler GmbH & Co. KG, Mainz-Kastel Federal Agency for the Prevention of Torture Viktoriastraße 35 65189 Wiesbaden Tel.: 0611-15758-18 Fax: 0611-15758-29 E-Mail: [email protected] An electronic version of this Annual Report can be retrieved from the “Annual Reports” section of the www.bsvf.de Internet site. 3 Article 1 of the Basic Law (Grundgesetz) (1) Human dignity shall be inviolable. To respect and protect it shall be the duty of all state authority. (2) The German people therefore acknowledge inviolable and inalienable human rights as the basis of every community, of peace and of justice in the world. (3) The following basic rights shall bind the legislature, the executive and the judiciary as directly applicable law. 4 List of specific abbreviations APT Association for the Prevention of Torture BPolG Federal Police Act (Bundespolizeigesetz) BRAS Regulations, Guidelines, Instructions, Collections of Lists and Reference Works (Bestimmungen, Richtlinien, Anweisungen, Sammlungen von Katalogen und Nach- schlagewerken) BwVollzO Ordinance on the Enforcement of Prison Sentences, Military Disciplinary Confinement, Youth Detention and Disciplinary Detention by authorities of the Federal Armed Forces (Verordnung über den Vollzug von Freiheitsstrafe, Strafarrest, Jugendarrest und Diszi- plinararrest durch Behörden der Bundeswehr) CAT Convention -

Annual Report 2012 Agency for the Prevention of Torture National

NationalNational Agency Agency forfor the the Prevention Prevention of of Torture Torture AnnualAnnual Report Report 2012 2012 of theof the Federal Federal Agency Agency andand of ofthe the Joint Joint Commission Commission ofof thethe StatesStates (Länder(Länder) ) PeriodPeriod under under review review 1 January1 January 2012 2012 – 31 – 31 December December 2012 2012 National Agency for the Prevention of Torture Annual Report 2012 Agency for the Prevention of Torture National National Agency for the Prevention of Torture Annual Report 2012 of the Federal Agency and of the Joint Commission of the States (Länder) Period under review 1 January 2012 – 31 December 2012 © 2013 National Agency for the Prevention of Torture All rights reserved Printed by: Heimsheim Prison, www.jva-heimsheim.de National Agency for the Prevention of Torture Viktoriastraße 35 65189 Wiesbaden Tel.: 0611-160 222 818 Fax: 0611-160 222 829 E-Mail: [email protected] www.nationale-stelle.de An electronic version of this Annual Report can be retrieved from the “Annual Reports” section at www.nationale-stelle.de. Foreword ................................................................................................................. 7 List of specific abbreviations ............................................................................... 11 I General information about the work of the National Agency ............... 12 1 History and legal foundation of the National Agency ................................... 12 2 The foundation created for the work ............................................................... -

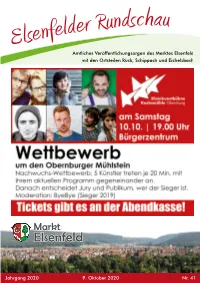

Elsenfelderrundschau

r Rundschau Elsenfelde Amtliches Veröffentlichungsorgan des Marktes Elsenfeld mit den Ortsteilen Rück, Schippach und Eichelsbach Markt Elsenfeld Jahrgang 2020 9. Oktober 2020 Nr. 41 Amtliches Veröffentlichungsorgan des Marktes Elsenfeld mit den Ortsteilen Rück, Schippach und Eichelsbach Montag: 8.00 - 12.00 Uhr und 14.00 - 16.00 Uhr Dienstag, Mittwoch, Freitag: 8.00 - 12.00 Uhr Donnerstag: 10.00 - 12.00 Uhr und 14.00 - 18.00 Uhr Telefon: 06022/5007-0 | Telefax: 06022/5007-66 E-Mail: [email protected] | Homepage: www.elsenfeld.de Amtliche Bekanntmachungen Bekanntmachung Am Montag, 12.10.2020, findet um 19.00 Uhr eine öffentliche Sitzung des Marktgemeinderates im großen Saal des Bürgerzentrums statt. Tagesordnung: Öffentlicher Teil 1. Anerkennung der Sitzungsniederschrift vom 14.09.2020 2. Bekanntgaben 3. Anträge der Fraktion SPD/Bündnis90-Die Grünen 3.1. Bauleitplanung bzw. Erschließung neuer Baugebiete nur nach Zwischenerwerb der be- troffenen Grundstücke durch den Markt Elsenfeld 3.2. Installation von Photovoltaikanlagen auf geeigneten gemeindlichen Liegenschaften 4. Vorstellung der Plangenehmigungsunterlagen durch die Westfrankenbahn für den behin- dertengerechten Umbau der Bahnunterführung, Anbindung West sowie des Mittelbahn- steigs und der Anbindung Ost mit Beschlussfassung 5. Entwicklung von circa 12 Baugrundstücken der Kath. Kirchenstiftung St. Pius im Be- reich des Flurstücks 3350/Gemarkung Schippach - Vorstellung des Projekts durch die Projektentwicklerin 6. Änderung der Satzung für die Kindertageseinrichtungen des Marktes Elsenfeld 7. Änderung über die Erhebung von Gebühren für die Benutzung der Kindertageseinrich- tungen des Marktes Elsenfeld 8. Neubau zweier Brunnen Abschlussbauwerke in Fertigteilbauweise auf dem Flurstück 11 im gemeindefreien Gebiet Forstwald, Bauherr: Stadt Erlenbach 9. Jahresmeldungen für das Städtebauförderungsprogramm 10. Kostenfeststellung für abgeschlossene Baumaßnahmen 11. -

Amts- Und Mitteilungsblatt Der Verwaltungsgemeinschaft Mespelbrunn Und Der Mitgliedsgemeinden Dammbach - Heimbuchenthal - Mespelbrunn Nr

Amts- und Mitteilungsblatt der Verwaltungsgemeinschaft Mespelbrunn und der Mitgliedsgemeinden Dammbach - Heimbuchenthal - Mespelbrunn Nr. 23 5. Juni 2020 43. Jahrgang Regelmäßige Öffnungszeiten der Verwaltungsgemeinschaft Mespelbrunn, Sitz Heimbuchenthal, Hauptstr. 81, 63872 Heimbuchenthal: montags bis freitags von 8 bis 12 Uhr und donnerstags von 14 bis 18 Uhr. Gemeinde DAMMBACH: Ihr Serviceunternehmen 1. Bürgermeisterin Waltraud Amrhein 942-125 Geschäftsstelle VG Mespelbrunn Vorzimmer 942-130, Fax 942-131 Rathaus Heimbuchenthal, Hauptstr. 81, Wintersbacher Str. 141 1594 Tel. 0 60 92 / 9 42-0, Fax 0 60 92 / 9 42-28, E-Mail: [email protected] [email protected] Bauhof 99 96 20, Handy 0151/25499263 Geschäftsleiterin Wasserversorgung AMME 09372/135958 Frau Christina Bathon 942-122 Mail: [email protected] Geschäftszimmer / Mitteilungsblatt Nur NOTFALL 0160/96314460 Vorzimmer Bürgermeisterin Fuchs, Gemeinde HEIMBUCHENTHAL: Mespelbrunn Frau Heid 942-123 1. Bürgermeister Rüdiger Stenger 942-126 Vorzimmer 942-130, Fax 942-131 Vorzimmer [email protected] Bürgermeisterin Amrhein Dammbach 942-130 Frau Laski, Frau Ringel 942-130 Kläranlage 64 79 Bürgermeister Stenger, Heimbuchenthal Bauhof 6386 od. 0151/14258954 Frau Laski, Frau Ringel 942-130 Wasserversorgung AMME 09372/135958 Bauamt Mail: [email protected] Frau Günther, Frau Goldhammer, 942-121 Nur NOTFALL 0160/96314460 Herr Englert 942-117 Gemeinde MESPELBRUNN: Kämmerer 1. Bürgermeisterin Stephanie Fuchs 942-120 Herr Aulbach 942-112 -

KW Mainaschaff Tafel 3

Fluss- und Handelsweg Main Ein Gewässer wird nutzbar gemacht Der Main und sein Tal prägen auf ihrem mehr als 300 km langen Lauf Von 1921 bis 1962 baute man den Main von Aschaffenburg bis Bamberg das Landschaftsbild Frankens. Im Maintal liegen die großen Siedlungs-, (Viereth) mit 28 Staustufen für die Schifffahrt und zur Nutzung der Was- Wirtschafts- und Industriestandorte. Entsprechend vielfältig sind die Nut- serkraft aus. Der Main wurde dabei hinsichtlich seiner Struktur und seines zungsansprüche des Menschen an den Fluss. Der Main ist als Bundes- Flusstyps grundlegend verändert. wasserstraße heute eine Verkehrsverbindung vom Rhein zur Donau ge- worden. Bereits in vorgeschichtlicher Zeit nutze man ihn als Verkehrsweg. Im Mittelalter war der Fluss bis Bamberg schiffbar. Bis ins 20. Jahrhundert nutzen Flößereien den Main zum Transport von Holz. Der natürliche Zu- stand des Mains Oben: Im Querschnitt von 1810 zeigt sich der Main in die Breite gehend mit geringem Tiefgang. Unten: war durch Laufver- Im Querschnitt von 1880 sind die Eingriffe in den Wasserlauf durch die „Mittelwasserkorrektion“ deut- lagerungen mit lich sichtbar. Buhnen am Rand sorgen für die Freihaltung der vom Menschen geschaffenen Fahrrinne. Abtrag und Anlan- dungen in Altar- men und Auenge- wässern gekenn- zeichnet. Hoch- wasser führte zu Überlu tungen der Aue und dabei zu Der freiließende Fluss wurde in ein staugeregeltes Gewässer umgewan- Sand- und Nähr- delt. Aus gewässerökologischer Sicht entspricht er heute einem Gewäs- stoffablagerun- sertyp, der mit einer Flussmündung vergleichbar ist. Das Einzugsgebiet des Mains gen. Der Main war an vielen Stellen breit, seicht und sumpfumlagert. Der Talraum war mit Auwald bewachsen. Sein Wasserstand konnte vom breiten wilden Strom bei Hochwasser bis hin zu einem ausgetrockneten schmalen „Flussrinnsal“ wechseln. -

2018 61St Annual German-American Steuben Parade Press

61st Annual German-American Steuben Parade of NYC Saturday, September 15, 2018 PRESS KIT The Parade: German-American Steuben Parade, NYC Parade’s Date: Saturday, September 15, 2018 starting at 12:00 noon Parade Route: 68th Street & Fifth Avenue to 86th Street & Fifth Avenue. General Chairman: Mr. Robert Radske Contacts: Email: [email protected] Phone: Sonia Juran Kulesza 347.495.2595 Grand Marshals: This year we are honored to have Mr. Peter Beyer, Member of the German Bundestag and Coordinator of Transatlantic Cooperation, and Mr. Helmut Jahn, renowned Architect, as our Grand Marshals. Both Mr. Beyer and Mr. Jahn are born in Germany, in Ratingen, North Rhine-Westphalia and Nuremberg, Bavaria respectively. Prior Grand Marshals: Some notable recent Grand Marshals have included: 6th generation member of the Flying Wallendas family – Nik Wallenda; Former Nobel Peace Prize recipient and United States National Security Advisor and Secretary of State of State under President Richard Nixon – Dr. Henry Kissinger; Long Island’s own actress, writer and supermodel - Ms. Carol Alt; beloved NY Yankees owner - Mr. George Steinbrenner; Sex Therapist and media personality - Dr. Ruth Westheimer; CNBC Correspondent – Contessa Brewer. Parade Sponsors: The Official Sponsors of the 61st Annual German-American Steuben Parade are the Max Kade Foundation, New York Turner Verein, The Cannstatter Foundation, The German Society of the City of New York, Dieter Pfisterer, Rossbach International, Wirsching Enterprise, Niche Import Company and Merican Reisen. Participants: The Committee will welcome over 300 participating groups from NY, NJ, CA, CT, IL, MA, MD, PA, TX and WI. In addition, 24 groups from Germany, Austria and Switzerland will attend this year’s Parade, totaling well over 2,000 marchers! Plus, 19 Floats will ride up Fifth Avenue in NYC. -

1 Landkreis Aschaffenburg 1.1 Stadt Alzenau I. Ufr. 1.1.1 1.1.2 1.1.3

Anlage 2 Grenzen der Erschließungszone (§ 3) Anlage 2 zur Verordnung über den „Naturpark Spessart“ Grenzen der Erschließungszone (§ 3) Die Erschließungszone umfaßt folgende Gebiete: 1 Landkreis Aschaffenburg 1.1 Stadt Alzenau i. UFr. 1.1.1 Nördlicher, östlicher und südlicher Teil der bebauten Ortslage von Michelbach einschließlich des angrenzenden Hahnenkammvorlandes – im Norden bis an die Naturparkgrenze – im Osten bis ca. 1100 m nordöstlich der Kirche (Flurlage „Tiefes Tal“) bis zur Staatsstraße 2305 und die Herrnmühle einschließend – im Südosten bis an den Waldrand im Hitziger Lochgraben – im Süden bis südlich der genannten Staatsstraße die Obermühle einschließend und bis ca. 150 m östlich des Kertelbachgrabens bis ca. 1100 m oberhalb der Mündung des Kertelbaches in die Kahl sowie 1.1.2 östlicher und südlicher Teil der bebauten Ortslage von Kälberau einschließlich des angrenzenden Hahnenkammvorlandes – im Norden und Westen bis an die Naturparkgrenze – im Osten bis an den Waldrand des Buchwaldes – im Süden – das Ziegeleigelände und die südöstlich vorgelagerten Feldflächen einschließend – bis zum Waldrand und zum Krebsbachgrund sowie 1.1.3 bebaute Ortslage von Wasserlos einschließlich des umgebenden Hahnenkammvorlandes – im Nordosten bis an den Flurweg von Alzenau zum „Schanzenkopf“ – im Osten bis an den Waldrand des „Schanzenkopf“ und weiter den Bergsporn südöstlich des Krankenhauses ausklammernd – den Weinberg an diesem Bergsporn, nördlich des Rückersbachtales, bis zum Waldrand einschließend – – im Süden bis ca. 400 m östlich parallel -

Internationally Coordinated Management Plan 2015 for the International River Basin District of the Rhine

Internationally Coordinated Management Plan 2015 for the International River Basin District of the Rhine (Part A = Overriding Part) December 2015 Imprint Joint report of The Republic of Italy, The Principality of Liechtenstein, The Federal Republic of Austria, The Federal Republic of Germany, The Republic of France, The Grand Duchy of Luxemburg, The Kingdom of Belgium, The Kingdom of the Netherlands With the cooperation of the Swiss Confederation Data sources Competent Authorities in the Rhine river basin district Coordination Rhine Coordination Committee in cooperation with the International Commission for the Protection of the Rhine (ICPR) Drafting of maps Federal Institute of Hydrology, Koblenz, Germany Publisher: International Commission for the Protection of the Rhine (ICPR) Kaiserin-Augusta-Anlagen 15, D 56068 Koblenz P.O. box 20 02 53, D 56002 Koblenz Telephone +49-(0)261-94252-0, Fax +49-(0)261-94252-52 Email: [email protected] www.iksr.org Translation: Karin Wehner ISBN 978-3-941994-72-0 © IKSR-CIPR-ICBR 2015 IKSR CIPR ICBR Bewirtschaftungsplan 2015 IFGE Rhein Contents Introduction .................................................................................. 6 1. General description .............................................................. 8 1.1 Surface water bodies in the IRBD Rhine ................................................. 11 1.2 Groundwater ...................................................................................... 12 2. Human activities and stresses .......................................... -

German Limes Road REMARKABLE RELICS of EARTHWORKS and OTHER MONUMENTS, RECONSTRUCTIONS and MUSEUMS

German Limes Road REMARKABLE RELICS OF EARTHWORKS AND OTHER MONUMENTS, RECONSTRUCTIONS AND MUSEUMS. THE GERMAN LIMES ROAD RUNS ALONG THE UPPER GERMAN-RAETIAN LIMES FROM BAD HÖNNINGEN /RHEINBROHL ON THE RHINE TO REGENSBURG ON THE DANUBE AS A TOURIST ROUTE. German Limes Road Dear Reader With this brochure we would like to invite you on a journey in the footsteps of the Romans along the Upper German-Raetian Limes recognized by UNESCO as a World Heritage site. This journey has been made German Limes Road possible for you by the association “Verein Deutsche German Limes Cycleway Limes-Straße e.V.”, which has laid out not only the German Limes Trail German Limes Road but also the German Limes Cycle- way for you. In addition to this, we would also like to The Upper German-Raetian Limes, the former border of the Roman introduce you to the Limes Trail. Empire between the Rhine and the Danube, recognised today by UNESCO as a World Heritage site, can be explored not only by car, but also by bike The association in which 93 municipalities, administra- or on foot along fully signposted routes. tive districts and tourism communities have come together, aims at generating an awareness in public of The German Limes Road, the German Limes Cycleway and the German the Limes as an archaeological monument of world his- Limes Trail offer ideal conditions for an encounter with witnesses of an torical significance. With its activities based on sharing ancient past as well as for recreational activities in beautiful natural land - knowledge and marketing, it wants to raise interest for scapes. -

Routenvorschläge Im Wanderparadies Räuberland

Das Herz im Spessart Routenvorschläge im Wanderparadies Räuberland www.raeuberland.com Inhaltsverzeichnis Informationen zum RÄUBERLAND .................................... 3 Dammbach Europäischer Kulturweg ................................................... 4 Alter Schulweg ................................................................. 6 Räuberlandweg 1 ............................................................. 8 Qualitätstour .................................................................... 10 Eschau Europäischer Kulturweg 1 ................................................ 12 Europaischer Kulturweg 2 ................................................ 14 Qualitätstour .................................................................... 16 Heimbuchenthal Europäischer Kulturweg ................................................... 18 Nordic-Walking-Touren .................................................... 20 Qualitätstour .................................................................... 24 Leidersbach Europäischer Kulturweg ................................................... 26 Nordic-Walking-Touren .................................................... 34 Qualitätstour .................................................................... 36 Mespelbrunn Europäischer Kulturweg ................................................... 40 Nordic-Walking-Touren .................................................... 42 Qualitätstour .................................................................... 44 Rothenbuch Europäischer Kulturweg .................................................. -

Erläuterungsbericht Zum Landschaftsplan

MARKT ELSENFELD Landkreis Miltenberg mit den Ortsteilen Elsenfeld, Rück-Schippach und Eichelsbach ERLÄUTERUNGSBERICHT ZUM LANDSCHAFTSPLAN Entwurf in der Fassung vom 08.04.2002 geändert / ergänzt 20.10.2003 24.05.2004 bearbeitet im Auftrag des Marktes Elsenfeld Sachbearbeiter: Martin Beil, Landschaftsarchitekt BDLA Tonja Weigand, Dipl. Ing. (TU) Landschafts- und Freiraumplanung Landschaftsplan Markt Elsenfeld II MARKT ELSENFELD, Landkreis Miltenberg mit den Ortsteilen Elsenfeld, Rück-Schippach und Eichelsbach LANDSCHAFTSPLAN bearbeitet im Auftrag des Marktes Elsenfeld Planungsbüro: Dietz und Partner, Landschaftsarchitekten BDLA Büro für Freiraumplanung Engenthal 42, 97725 Elfershausen Sachbearbeiter: Martin Beil, Landschaftsarchitekt BDLA Tonja Weigand, Dipl. Ing. (TU) Landschafts- und Freiraumplanung Landschaftsplan Markt Elsenfeld III INHALTSVERZEICHNIS: 1. EINFÜHRUNG ......................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Ziele und Aufgaben der Landschaftsplanung ........................................................................ 1 1.2 Verfahren / Gesetzliche Grundlagen..................................................................................... 1 1.3 Überblick über den Planungsraum ......................................................................................... 3 1.4 Naturschutzrechtliche Vorgaben ............................................................................................ 4 1.4.1 Vorgaben der Raumordnung und Landesplanung (Regionalplan der -

Master Plan Migratory Fish Rhine

Master Plan Migratory Fish Rhine Report No. 179 Imprint Publisher: International Commission for the Protection of the Rhine (ICPR) Kaiserin-Augusta-Anlagen 15, D 56068 Koblenz P.O. box 20 02 53, D 56002 Koblenz Telephone +49-(0)261-94252-0, Fax +49-(0)261-94252-52 Email: [email protected] www.iksr.org ISBN 978-3-941994-09-6 © IKSR-CIPR-ICBR 2009 Report 179e.doc Internationale Kommission zum Schutz des Rheins International Commission for the Protection of the Rhine Commission Internationale pour la Protection du Rhin Internationale Commissie ter Bescherming van de Rijn Master Plan Migratory Fish Rhine ICPR report no. 179 1. Initial conditions ..................................................................................... 2 2. Background............................................................................................ 3 3. Already implemented measures for anadromous migratory fish...................... 5 4. Measures planned for anadromous migratory fish in the different sections of the Rhine.................................................................................................... 6 4.1 River Continuity and Habitats...................................................................... 6 4.1.1 Delta Rhine............................................................................................ 6 4.1.2 Lower Rhine........................................................................................... 7 4.1.3 Middle Rhine .........................................................................................