Hadath, Beirut 1976

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oral History Interview with Beatrice Wood, 1976 August 26

Oral history interview with Beatrice Wood, 1976 August 26 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Beatrice Wood on August 26, 1976. The interview was conducted by Paul Karlstrom for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Interview PAUL KARLSTROM: I'm delighted that I have a chance to talk with you and learn something about your own background and something about your work as a potter. Maybe you could tell me a little bit about your family and where you were born, and the early days. BEATRICE WOOD: I'll do that briefly. PAUL KARLSTROM: O.K. BEATRICE WOOD: I was born in San Francisco. PAUL KARLSTROM: Oh really? BEATRICE WOOD: And I tell everybody in 1703. That solves the question. And I was very unhappy in my family. We moved immediately to New York and then I was taken over to Paris and I learned to read French before I learned to read English. I was in a convent for a year. Then they brought me back and put me in a private school. I went to Miss Ely's, which was the fashionable finishing school in those years. PAUL KARLSTROM: Is that in the New York area? BEATRICE WOOD: In New York. It's now completely nonexistent. -

THE CLASS.Fdr

Entre les Murs (The Class) Written by Laurent Cantet, Robin Campillo and François Bégaudeau Based on the novel "Entre les murs" by François Bégaudeau published by Verticales, 2006 Directed par Laurent Cantet Developed with the backing of the Centre National de la Cinématographie, the Procirep and the European Union's Media Programme INT. CAFÉ - DAY The first morning of the new school year. In a Paris café, leaning on the bar, FRANÇOIS, 35 or so, peacefully sips coffee. In the background, we can vaguely make out a conversation about the results of the presidential election. François looks at his watch and seems to take a deep breath as if stepping onto a stage. EXT. STREET - DAY François comes out of the café. Across the street, we discover a large building whose slightly outdated façade is not particularly welcoming. He walks over to the imposing entrance that bears the shield of the City of Paris in wrought iron and beneath which we read “JAURES MIDDLE SCHOOL”. On the opposite sidewalk, coming from the other end of the street, a small group of teachers hurries towards the entrance. François hears them joking. VINCENT He’s a really great guy, not the back- slapping type but… François greets them in passing. INT. CORRIDORS - SCHOOL - DAY We discover the school’s deserted corridors. Through the doorway of a classroom, François sees a few cleaners who, in a very calm atmosphere, clean the tables and line them up neatly, wash the windows… A short distance further on, a man in overalls applies one last coat of paint to an administrative notice board. -

Music for Guitar

So Long Marianne Leonard Cohen A Bm Come over to the window, my little darling D A Your letters they all say that you're beside me now I'd like to try to read your palm then why do I feel so alone G D I'm standing on a ledge and your fine spider web I used to think I was some sort of gypsy boy is fastening my ankle to a stone F#m E E4 E E7 before I let you take me home [Chorus] For now I need your hidden love A I'm cold as a new razor blade Now so long, Marianne, You left when I told you I was curious F#m I never said that I was brave It's time that we began E E4 E E7 [Chorus] to laugh and cry E E4 E E7 Oh, you are really such a pretty one and cry and laugh I see you've gone and changed your name again A A4 A And just when I climbed this whole mountainside about it all again to wash my eyelids in the rain [Chorus] Well you know that I love to live with you but you make me forget so very much Oh, your eyes, well, I forget your eyes I forget to pray for the angels your body's at home in every sea and then the angels forget to pray for us How come you gave away your news to everyone that you said was a secret to me [Chorus] We met when we were almost young deep in the green lilac park You held on to me like I was a crucifix as we went kneeling through the dark [Chorus] Stronger Kelly Clarkson Intro: Em C G D Em C G D Em C You heard that I was starting over with someone new You know the bed feels warmer Em C G D G D But told you I was moving on over you Sleeping here alone Em Em C You didn't think that I'd come back You know I dream in colour -

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed up 311 Down

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed Up 311 Down 702 Where My Girls At 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 Little Bit More, A 911 More Than A Woman 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 10,000 Maniacs More Than This 10,000 Maniacs These Are The Days 10CC Donna 10CC Dreadlock Holiday 10CC I'm Mandy 10CC I'm Not In Love 10CC Rubber Bullets 10CC Things We Do For Love, The 10CC Wall Street Shuffle 112 & Ludacris Hot & Wet 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac California Love 2 Pac Thugz Mansion 2 Unlimited No Limits 20 Fingers Short Dick Man 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 3 Doors Down Duck & Run 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Its not my time 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors Down Loser 3 Doors Down Road I'm On, The 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 38 Special If I'd Been The One 38 Special Second Chance 3LW I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) 3LW No More 3LW No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) 3LW Playas Gon' Play 3rd Strike Redemption 3SL Take It Easy 3T Anything 3T Tease Me 3T & Michael Jackson Why 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Stairsteps Ooh Child 50 Cent Disco Inferno 50 Cent If I Can't 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent P.I.M.P. (Radio Version) 50 Cent Wanksta 50 Cent & Eminem Patiently Waiting 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 21 Questions 5th Dimension Aquarius_Let the sunshine inB 5th Dimension One less Bell to answer 5th Dimension Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension Up Up & Away 5th Dimension Wedding Blue Bells 5th Dimension, The Last Night I Didn't Get To Sleep At All 69 Boys Tootsie Roll 8 Stops 7 Question -

APPENDIX D the Interview Transcriptions Olivia

The Experience of Coming Out 207 APPENDIX D The Interview Transcriptions Olivia [1] Can you tell me when the possibility first occurred to you that you were sexually attracted to women? I think I was about…23. I was asexual…for a long time. Through undergrad and the first part of grad school. A woman approached me. Many women would approach me. And um…a lot of people assumed I was gay before I even acknowledged or even dealt with it. Once I left my father’s house, I just was not sexual. [2] So you were 23 years old, and then what happened? You were out of the house. I was out of the house. I was in graduate school already. Her name was Sara Lincoln. She befriended me. There were a couple of women but I didn’t really know what the response was. To give you some background on that, my mother left my father when I was ten. Okay? Um, So he…there was four of us, and he raised us. I took her place in the household. Okay, um …[pause] and I was a chubby child. I was bulimic. And as a young adult, I didn’t want the weight. I didn’t like um “you have a fat ass” type of thing. So even now my sister goes through this thing about how I eat. Um…If I gain, you know, too much weight I [shifted around on the couch with a deep breath] get real paranoid-hysterical? Because I don’t like the attraction of the body. -

Fascination Viewer Friendly TV Journalism Nancy Graham Holm

Fascination Front matter Fascination Viewer Friendly TV Journalism Nancy Graham Holm Aarhus Denmark AMSTERDAM • BOSTON • HEIDELBERG • LONDON • NEW YORK • OXFORD PARIS • SAN DIEGO • SAN FRANCISCO • SINGAPORE • SYDNEY • TOKYO Elsevier 32 Jamestown Road, London NW1 7BY 225 Wyman Street, Waltham, MA 02451, USA First edition 2012 © 2007 by Nancy Graham Holm and Ajour. Published by Elsevier Inc. 2012. All Rights Reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Details on how to seek permission, further information about the Publisher’s permissions policies and our arrangement with organizations such as the Copyright Clearance Center and the Copyright Licensing Agency, can be found at our website: www.elsevier.com/permissions This book and the individual contributions contained in it are protected under copyright by the Publisher (other than as may be noted herein). Notices Knowledge and best practice in this field are constantly changing. As new research and experience broaden our understanding, changes in research methods, professional practices, or medical treatment may become necessary. Practitioners and researchers must always rely on their own experience and knowledge in evaluating and using any information, methods, compounds, or experiments described herein. In using such information or methods they should be mindful of their own safety and the safety of others, including parties for whom they have a professional responsibility. To the fullest extent of the law, neither the Publisher nor the authors, contributors, or editors, assume any liability for any injury and/or damage to persons or property as a matter of products liability, negligence or otherwise, or from any use or operation of any methods, products, instructions, or ideas contained in the material herein. -

1 Giant Leap Dreadlock Holiday -- 10Cc I'm Not in Love

Dumb -- 411 Chocolate -- 1975 My Culture -- 1 Giant Leap Dreadlock Holiday -- 10cc I'm Not In Love -- 10cc Simon Says -- 1910 Fruitgum Company The Sound -- 1975 Wiggle It -- 2 In A Room California Love -- 2 Pac feat. Dr Dre Ghetto Gospel -- 2 Pac feat. Elton John So Confused -- 2 Play feat. Raghav & Jucxi It Can't Be Right -- 2 Play feat. Raghav & Naila Boss Get Ready For This -- 2 Unlimited Here I Go -- 2 Unlimited Let The Beat Control Your Body -- 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive -- 2 Unlimited No Limit -- 2 Unlimited The Real Thing -- 2 Unlimited Tribal Dance -- 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone -- 2 Unlimited Short Short Man -- 20 Fingers feat. Gillette I Want The World -- 2Wo Third3 Baby Cakes -- 3 Of A Kind Don't Trust Me -- 3Oh!3 Starstrukk -- 3Oh!3 ft Katy Perry Take It Easy -- 3SL Touch Me, Tease Me -- 3SL feat. Est'elle 24/7 -- 3T What's Up? -- 4 Non Blondes Take Me Away Into The Night -- 4 Strings Dumb -- 411 On My Knees -- 411 feat. Ghostface Killah The 900 Number -- 45 King Don't You Love Me -- 49ers Amnesia -- 5 Seconds Of Summer Don't Stop -- 5 Seconds Of Summer She Looks So Perfect -- 5 Seconds Of Summer She's Kinda Hot -- 5 Seconds Of Summer Stay Out Of My Life -- 5 Star System Addict -- 5 Star In Da Club -- 50 Cent 21 Questions -- 50 Cent feat. Nate Dogg I'm On Fire -- 5000 Volts In Yer Face -- 808 State A Little Bit More -- 911 Don't Make Me Wait -- 911 More Than A Woman -- 911 Party People.. -

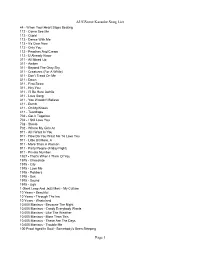

Augsome Karaoke Song List Page 1

AUGSome Karaoke Song List 44 - When Your Heart Stops Beating 112 - Come See Me 112 - Cupid 112 - Dance With Me 112 - It's Over Now 112 - Only You 112 - Peaches And Cream 112 - U Already Know 311 - All Mixed Up 311 - Amber 311 - Beyond The Gray Sky 311 - Creatures (For A While) 311 - Don't Tread On Me 311 - Down 311 - First Straw 311 - Hey You 311 - I'll Be Here Awhile 311 - Love Song 311 - You Wouldn't Believe 411 - Dumb 411 - On My Knees 411 - Teardrops 702 - Get It Together 702 - I Still Love You 702 - Steelo 702 - Where My Girls At 911 - All I Want Is You 911 - How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 - Little Bit More, A 911 - More Than A Woman 911 - Party People (Friday Night) 911 - Private Number 1927 - That's When I Think Of You 1975 - Chocolate 1975 - City 1975 - Love Me 1975 - Robbers 1975 - Sex 1975 - Sound 1975 - Ugh 1 Giant Leap And Jazz Maxi - My Culture 10 Years - Beautiful 10 Years - Through The Iris 10 Years - Wasteland 10,000 Maniacs - Because The Night 10,000 Maniacs - Candy Everybody Wants 10,000 Maniacs - Like The Weather 10,000 Maniacs - More Than This 10,000 Maniacs - These Are The Days 10,000 Maniacs - Trouble Me 100 Proof Aged In Soul - Somebody's Been Sleeping Page 1 AUGSome Karaoke Song List 101 Dalmations - Cruella de Vil 10Cc - Donna 10Cc - Dreadlock Holiday 10Cc - I'm Mandy 10Cc - I'm Not In Love 10Cc - Rubber Bullets 10Cc - Things We Do For Love, The 10Cc - Wall Street Shuffle 112 And Ludacris - Hot And Wet 12 Gauge - Dunkie Butt 12 Stones - Crash 12 Stones - We Are One 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

The Psychological Concepts in Taylor Swift's "Blank Space"

THE PSYCHOLOGICAL CONCEPTS IN TAYLOR SWIFT'S "BLANK SPACE" A FINAL PROJECT In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement For S-1 Degree in American Cultural Studies In English Department, Faculty of Humanities Diponegoro University Submitted by: Novia Putri Anindhita 13020111130073 FACULTY OF HUMANITIES DIPONEGORO UNIVERSITY SEMARANG 2015 x PRONOUNCEMENT I state truthfully that this project is compiled by me without taking the results from other research in any university, in S-1, S-2, and S-3 degree and diploma. In addition, I ascertain that I do not take the material from other publications or someone’s work except for the references mentioned in the bibliography. Semarang, 9 February 2016 Novia Putri Anindhita ii APPROVAL Approved by Advisor, Retno Wulandari, S.S, M.A. NIP. 19750525 200501 2 002 iii VALIDATION Approved by Strata I Final Project Examination Committee Faculty of Humanities Diponegoro University on March 2016 Chair Person First Member Arido Laksono, S.S, M.Hum. Dra. Christine Resnitriwati, M.Hum. NIP. 19750711 199903 1 002 NIP.19560216 198303 2 001 Second Member Third Member Sukarni Suryaningsih, S.S., M.Hum Drs. Mualimin, M.Hum. NIP. 19721223 199802 2 001 NIP. 19611110 198710 1 001 iv MOTTO AND DEDICATION Life is like riding a bicycle. To keep your balance, you must keep moving (Albert Enstein). You’re lucky enough to be different, never change (Taylor Swift). This final project is dedicated to my beloved parents. v ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Praise be to Allah, who has given strength and spirit to this final project on “The Psychological Concepts in Taylor Swift’s “Blank Space”” came to a completion. -

06/18 Vol. 5 Freestyle

06/18 Vol. 5 Freestyle memoirmixtapes.com Memoir Mixtapes Vol. 5: Freestyle June 15, 2018 Created by Samantha Lamph/Len Curated and edited by Samantha Lamph/Len and Kevin D. Woodall Visual identity design by J. S. Robson Cover stock photography courtesy of Vanessa Ives, publically available on Unsplash.com Special thanks to our reader, Benjamin Selesnick Letters from the Editors Welcome to Memoir Mixtapes Vol. 5: Freestyle. Hello again, everyone. (And “hey” to new readers!) Whether you’ve been reading MM since Vol.1, or this is your first time visiting our site, we’re so happy you’re This Volume is a little different from our usual here. publications. As Sam already mentioned, we hear “I have something I want to write for Memoir Mixtapes, Since we started Memoir Mixtapes, one of the most but it doesn’t fit the prompt!” pretty regularly. common questions we’ve been asked—volume after volume—came from readers who were eager to be a Like, a lot. part of the project. These potential contributors had a musically-inspired story to share, but it didn’t quite fit And so, after hearing those words enough we decided the current theme. We didn’t want to miss out on that we’d OPEN THE FUCKING PIT UP lol. those pieces, so this time around, we decided to put our themed issues on hold to give those writers their Our contributors, free of a prompt, were able to spread chance to bring those stories to the world. their wings wider this time, and the result is some truly unique work that, once again, I’m incredibly While it was quite a bit more challenging here on our proud to publish. -

The Description of Moral Value in Maher Zain's Thank

THE DESCRIPTION OF MORAL VALUE IN MAHER ZAIN’S THANK YOU ALLAH ALBUM A PAPER BY WEN DENIS SIMAHATE REG. NO. 152202051 DIPLOMA III ENGLISH STUDY PROGRAM FACULTY OF CULTURAL STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF SUMATERA UTARA MEDAN 2018 UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA AUTHOR’S DECLARATION I, WEN DENIS SIMAHATE declare that I am the sole author of this paper. This paper except where the reference is made in the text of this paper. This paper contains no material published elsewhere or extracted in whole or in part from a paper by which I have qualified for or awarded degree. No other person’s work has been used without due acknowledgement in the main text of this paper. This paper has not been submitted for award of another degree in any tertiary education. Signed : Date : November 29th, 2018 i UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA COPYRIGHT DECLARATION Name : WEN DENIS SIMAHATE Tittle of paper : The Description of Moral Value in Maher Zain’s Thank You Allah Album Qualification : D-III / AhliMadya Study Program : English I am willing that my paper should be available for reproduction at the discretion of the liberatarian of the Diploma III English Department Faculty of Culture Studies USU on the understanding that users are made aware of their obligation under law of the Republic of Indonesia. Signed : Date : Thursday, November 29th, 2018 ii UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA ABSTRAK Penelitian ini berjudul “A Description of Moral Values in Maher Zain’s Thank You Allah album”. Tujuan penelitian ini untuk mendeskripsikan nilai moral dan makna nilai moral yang tergambarkan dalam kehidupan melalui album Maher Zain yang berjudul Thank You Allah. -

Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison

Invisible Man By Ralph Ellison Back Cover: Winner of the National Book Award for fiction. Acclaimed by a 1965 Book Week poll of 200 prominent authors, critics, and editors as "the most distinguished single work published in the last twenty years." Unlike any novel you've ever read, this is a richly comic, deeply tragic, and profoundly soul-searching story of one young Negro's baffling experiences on the road to self-discovery. From the bizarre encounter with the white trustee that results in his expulsion from a Southern college to its powerful culmination in New York's Harlem, his story moves with a relentless drive: -- the nightmarish job in a paint factory -- the bitter disillusionment with the "Brotherhood" and its policy of betrayal -- the violent climax when screaming tensions are released in a terrifying race riot. This brilliant, monumental novel is a triumph of storytelling. It reveals profound insight into every man's struggle to find his true self. "Tough, brutal, sensational. it blazes with authentic talent." -- New York Times "A work of extraordinary intensity -- powerfully imagined and written with a savage, wryly humorous gusto." -- The Atlantic Monthly "A stunning blockbuster of a book that will floor and flabbergast some people, bedevil and intrigue others, and keep everybody reading right through to its explosive end." -- Langston Hughes "Ellison writes at a white heat, but a heat which he manipulates like a veteran." -- Chicago Sun-Times TO IDA COPYRIGHT, 1947, 1948, 1952, BY RALPH ELLISON All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. For information address Random House, Inc., 457 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10022.