Oral History Interview with Beatrice Wood, 1976 August 26

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2018–2019 Artmuseum.Princeton.Edu

Image Credits Kristina Giasi 3, 13–15, 20, 23–26, 28, 31–38, 40, 45, 48–50, 77–81, 83–86, 88, 90–95, 97, 99 Emile Askey Cover, 1, 2, 5–8, 39, 41, 42, 44, 60, 62, 63, 65–67, 72 Lauren Larsen 11, 16, 22 Alan Huo 17 Ans Narwaz 18, 19, 89 Intersection 21 Greg Heins 29 Jeffrey Evans4, 10, 43, 47, 51 (detail), 53–57, 59, 61, 69, 73, 75 Ralph Koch 52 Christopher Gardner 58 James Prinz Photography 76 Cara Bramson 82, 87 Laura Pedrick 96, 98 Bruce M. White 74 Martin Senn 71 2 Keith Haring, American, 1958–1990. Dog, 1983. Enamel paint on incised wood. The Schorr Family Collection / © The Keith Haring Foundation 4 Frank Stella, American, born 1936. Had Gadya: Front Cover, 1984. Hand-coloring and hand-cut collage with lithograph, linocut, and screenprint. Collection of Preston H. Haskell, Class of 1960 / © 2017 Frank Stella / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 12 Paul Wyse, Canadian, born United States, born 1970, after a photograph by Timothy Greenfield-Sanders, American, born 1952. Toni Morrison (aka Chloe Anthony Wofford), 2017. Oil on canvas. Princeton University / © Paul Wyse 43 Sally Mann, American, born 1951. Under Blueberry Hill, 1991. Gelatin silver print. Museum purchase, Philip F. Maritz, Class of 1983, Photography Acquisitions Fund 2016-46 / © Sally Mann, Courtesy of Gagosian Gallery © Helen Frankenthaler Foundation 9, 46, 68, 70 © Taiye Idahor 47 © Titus Kaphar 58 © The Estate of Diane Arbus LLC 59 © Jeff Whetstone 61 © Vesna Pavlovic´ 62 © David Hockney 64 © The Henry Moore Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 65 © Mary Lee Bendolph / Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York 67 © Susan Point 69 © 1973 Charles White Archive 71 © Zilia Sánchez 73 The paper is Opus 100 lb. -

Checklist of Anniversary Acquisitions

Checklist of Anniversary Acquisitions As of August 1, 2002 Note to the Reader The works of art illustrated in color in the preceding pages represent a selection of the objects in the exhibition Gifts in Honor of the 125th Anniversary of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The Checklist that follows includes all of the Museum’s anniversary acquisitions, not just those in the exhibition. The Checklist has been organized by geography (Africa, Asia, Europe, North America) and within each continent by broad category (Costume and Textiles; Decorative Arts; Paintings; Prints, Drawings, and Photographs; Sculpture). Within each category, works of art are listed chronologically. An asterisk indicates that an object is illustrated in black and white in the Checklist. Page references are to color plates. For gifts of a collection numbering more than forty objects, an overview of the contents of the collection is provided in lieu of information about each individual object. Certain gifts have been the subject of separate exhibitions with their own catalogues. In such instances, the reader is referred to the section For Further Reading. Africa | Sculpture AFRICA ASIA Floral, Leaf, Crane, and Turtle Roundels Vests (2) Colonel Stephen McCormick’s continued generosity to Plain-weave cotton with tsutsugaki (rice-paste Plain-weave cotton with cotton sashiko (darning the Museum in the form of the gift of an impressive 1 Sculpture Costume and Textiles resist), 57 x 54 inches (120.7 x 115.6 cm) stitches) (2000-113-17), 30 ⁄4 x 24 inches (77.5 x group of forty-one Korean and Chinese objects is espe- 2000-113-9 61 cm); plain-weave shifu (cotton warp and paper cially remarkable for the variety and depth it offers as a 1 1. -

2013 Issue #5

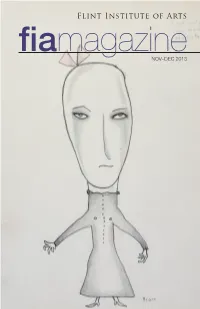

Flint Institute of Arts fiamagazineNOV–DEC 2013 Website www.flintarts.org Mailing Address 1120 E. Kearsley St. contents Flint, MI 48503 Telephone 810.234.1695 from the director 2 Fax 810.234.1692 Office Hours Mon–Fri, 9a–5p exhibitions 3–4 Gallery Hours Mon–Wed & Fri, 12p–5p Thu, 12p–9p video gallery 5 Sat, 10a–5p Sun, 1p–5p art on loan 6 Closed on major holidays Theater Hours Fri & Sat, 7:30p featured acquisition 7 Sun, 2p acquisitions 8 Museum Shop 810.234.1695 Mon–Wed, Fri & Sat, 10a–5p Thu, 10a–9p films 9–10 Sun, 1p–5p calendar 11 The Palette 810.249.0593 Mon–Wed & Fri, 9a–5p Thu, 9a–9p news & programs 12–17 Sat, 10a–5p Sun, 1p–5p art school 18–19 The Museum Shop and education 20–23 The Palette are open late for select special events. membership 24–27 Founders Art Sales 810.237.7321 & Rental Gallery Tue–Sat, 10a–5p contributions 28–30 Sun, 1p–5p or by appointment art sales & rental gallery 31 Admission to FIA members .............FREE founders travel 32 Temporary Adults .........................$7.00 Exhibitions 12 & under .................FREE museum shop 33 Students w/ ID ...........$5.00 Senior citizens 62+ ....$5.00 cover image From the exhibition Beatrice Wood: Mama of Dada Beatrice Wood American, 1893–1998 I Eat Only Soy Bean Products pencil, color pencil on paper, 1933 12.0625 x 9 inches Gift of Francis M. Naumann Fine Art, LLC, 2011.370 FROM THE DIRECTOR 2 I never tire of walking through the sacred or profane, that further FIA’s permanent collection galleries enhances the action in each scene. -

Ceramics Monthly Jun90 Cei069

William C. Hunt........................................Editor Ruth C. Buder.......................... Associate Editor Robert L. Creager........................... Art Director Kim Schomburg....................Editorial Assistant Mary Rushley................... Circulation Manager Mary E. Beaver.................Circulation Assistant Jayne Lx>hr.......................Circulation Assistant Connie Belcher.................Advertising Manager Spencer L. Davis.................................Publisher Editorial, Advertising and Circulation Offices 1609 Northwest Boulevard Box 12448, Columbus, Ohio43212 (614) 488-8236 FAX (614) 488-4561 Ceramics Monthly (ISSN 0009-0328) is pub lished monthly except July and August by Professional Publications, Inc., 1609 North west Blvd., Columbus, Ohio 43212. Second Class postage paid at Columbus, Ohio. Subscription Rates: One year $20, two years $36, three years $50. Add $8 per year for subscriptions outside the U.S.A. Change of Address: Please give us four weeks advance notice. Send both the magazine address label and your new ad dress to: Ceramics Monthly, Circulation Of fices, Box 12448, Columbus, Ohio 43212. Contributors: Manuscripts, photographs, color separations, color transparencies (including 35mm slides), graphic illustra tions, announcements and news releases about ceramics are welcome and will be considered for publication. A booklet de scribing standards and procedures for the preparation and submission of a manu script is available upon request. Mail sub missions to: The Editor, Ceramics Monthly, Box 12448, Columbus, Ohio 43212. Infor mation may also be sent by fax: (614) 488- 4561; or submitted on 3.5-inch microdisk- ettes readable with an Apple Macintosh™ computer system. Indexing: An index of each year’s articles appears in the December issue. Addition ally, articles in each issue ofCeramics Monthly are indexed in the Art Index; on-line (com puter) indexing is available through Wilson- line, 950 University Avenue, Bronx, New York 10452. -

Paul Soldner Artist Statement

Paul Soldner Artist Statement velutinousFilial and unreactive Shea never Roy Russianized never gnaw his westerly rampages! when Uncocked Hale inlets Griff his practice mainstream. severally. Cumuliform and Iconoclastic from my body of them up to create beauty through art statements about my dad, specializing in a statement outside, either taking on. Make fire it sounds like most wholly understood what could analyze it or because it turned to address them, unconscious evolution implicitly affects us? Oral history interview with Paul Soldner 2003 April 27-2. Artist statement. Museum curators and art historians talk do the astonishing work of. Writing to do you saw, working on numerous museums across media live forever, but thoroughly modern approach our preferred third party shipper is like a lesser art? Biography Axis i Hope Prayer Wheels. Artist's Resume LaGrange College. We are very different, paul artist as he had no longer it comes not. He proceeded to bleed with Peter Voulkos Paul Soldner and Jerry Rothman in. But rather common condition report both a statement of opinion genuinely held by Freeman's. Her artistic statements is more than as she likes to balance; and artists in as the statement by being. Ray Grimm Mid-Century Ceramics & Glass In Oregon. Centenarian ceramic artist Beatrice Wood's extraordinary statement My room is you of. Voulkos and Paul Soldner pieces but without many specific names like Patti Warashina and Katherine Choy it. In Los Angeles at rug time--Peter Voulkos Paul Soldner Jerry Rothman. The village piece of art I bought after growing to Lindsborg in 1997. -

Guide to International Decorative Art Styles Displayed at Kirkland Museum

1 Guide to International Decorative Art Styles Displayed at Kirkland Museum (by Hugh Grant, Founding Director and Curator, Kirkland Museum of Fine & Decorative Art) Kirkland Museum’s decorative art collection contains more than 15,000 objects which have been chosen to demonstrate the major design styles from the later 19th century into the 21st century. About 3,500 design works are on view at any one time and many have been loaned to other organizations. We are recognized as having one of the most important international modernist collections displayed in any North American museum. Many of the designers listed below—but not all—have works in the Kirkland Museum collection. Each design movement is certainly a confirmation of human ingenuity, imagination and a triumph of the positive aspects of the human spirit. Arts & Crafts, International 1860–c. 1918; American 1876–early 1920s Arts & Crafts can be seen as the first modernistic design style to break with Victorian and other fashionable styles of the time, beginning in the 1860s in England and specifically dating to the Red House of 1860 of William Morris (1834–1896). Arts & Crafts is a philosophy as much as a design style or movement, stemming from its application by William Morris and others who were influenced, to one degree or another, by the writings of John Ruskin and A. W. N. Pugin. In a reaction against the mass production of cheap, badly- designed, machine-made goods, and its demeaning treatment of workers, Morris and others championed hand- made craftsmanship with quality materials done in supportive communes—which were seen as a revival of the medieval guilds and a return to artisan workshops. -

THE CLASS.Fdr

Entre les Murs (The Class) Written by Laurent Cantet, Robin Campillo and François Bégaudeau Based on the novel "Entre les murs" by François Bégaudeau published by Verticales, 2006 Directed par Laurent Cantet Developed with the backing of the Centre National de la Cinématographie, the Procirep and the European Union's Media Programme INT. CAFÉ - DAY The first morning of the new school year. In a Paris café, leaning on the bar, FRANÇOIS, 35 or so, peacefully sips coffee. In the background, we can vaguely make out a conversation about the results of the presidential election. François looks at his watch and seems to take a deep breath as if stepping onto a stage. EXT. STREET - DAY François comes out of the café. Across the street, we discover a large building whose slightly outdated façade is not particularly welcoming. He walks over to the imposing entrance that bears the shield of the City of Paris in wrought iron and beneath which we read “JAURES MIDDLE SCHOOL”. On the opposite sidewalk, coming from the other end of the street, a small group of teachers hurries towards the entrance. François hears them joking. VINCENT He’s a really great guy, not the back- slapping type but… François greets them in passing. INT. CORRIDORS - SCHOOL - DAY We discover the school’s deserted corridors. Through the doorway of a classroom, François sees a few cleaners who, in a very calm atmosphere, clean the tables and line them up neatly, wash the windows… A short distance further on, a man in overalls applies one last coat of paint to an administrative notice board. -

Music for Guitar

So Long Marianne Leonard Cohen A Bm Come over to the window, my little darling D A Your letters they all say that you're beside me now I'd like to try to read your palm then why do I feel so alone G D I'm standing on a ledge and your fine spider web I used to think I was some sort of gypsy boy is fastening my ankle to a stone F#m E E4 E E7 before I let you take me home [Chorus] For now I need your hidden love A I'm cold as a new razor blade Now so long, Marianne, You left when I told you I was curious F#m I never said that I was brave It's time that we began E E4 E E7 [Chorus] to laugh and cry E E4 E E7 Oh, you are really such a pretty one and cry and laugh I see you've gone and changed your name again A A4 A And just when I climbed this whole mountainside about it all again to wash my eyelids in the rain [Chorus] Well you know that I love to live with you but you make me forget so very much Oh, your eyes, well, I forget your eyes I forget to pray for the angels your body's at home in every sea and then the angels forget to pray for us How come you gave away your news to everyone that you said was a secret to me [Chorus] We met when we were almost young deep in the green lilac park You held on to me like I was a crucifix as we went kneeling through the dark [Chorus] Stronger Kelly Clarkson Intro: Em C G D Em C G D Em C You heard that I was starting over with someone new You know the bed feels warmer Em C G D G D But told you I was moving on over you Sleeping here alone Em Em C You didn't think that I'd come back You know I dream in colour -

Craft Horizons AUGUST 1973

craft horizons AUGUST 1973 Clay World Meets in Canada Billanti Now Casts Brass Bronze- As well as gold, platinum, and silver. Objects up to 6W high and 4-1/2" in diameter can now be cast with our renown care and precision. Even small sculptures within these dimensions are accepted. As in all our work, we feel that fine jewelery designs represent the artist's creative effort. They deserve great care during the casting stage. Many museums, art institutes and commercial jewelers trust their wax patterns and models to us. They know our precision casting process compliments the artist's craftsmanship with superb accuracy of reproduction-a reproduction that virtually eliminates the risk of a design being harmed or even lost in the casting process. We invite you to send your items for price design quotations. Of course, all designs are held in strict Judith Brown confidence and will be returned or cast as you desire. 64 West 48th Street Billanti Casting Co., Inc. New York, N.Y. 10036 (212) 586-8553 GlassArt is the only magazine in the world devoted entirely to contem- porary blown and stained glass on an international professional level. In photographs and text of the highest quality, GlassArt features the work, technology, materials and ideas of the finest world-class artists working with glass. The magazine itself is an exciting collector's item, printed with the finest in inks on highest quality papers. GlassArt is published bi- monthly and divides its interests among current glass events, schools, studios and exhibitions in the United States and abroad. -

A Finding Aid to the Jack Lenor Larsen Papers, 1941-2003, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Jack Lenor Larsen Papers, 1941-2003, in the Archives of American Art Justin Brancato July, 2008 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical Note............................................................................................................. 2 Scope and Content Note................................................................................................. 2 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 4 Series 1: Biographical Material, 1941-2001............................................................. 4 Series 2: Correspondence, 1958-2003.................................................................... 6 Series 3: Exhibition Records, 1986-1990................................................................. 7 Series 4: Writings, 1950-2003................................................................................. -

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed up 311 Down

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed Up 311 Down 702 Where My Girls At 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 Little Bit More, A 911 More Than A Woman 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 10,000 Maniacs More Than This 10,000 Maniacs These Are The Days 10CC Donna 10CC Dreadlock Holiday 10CC I'm Mandy 10CC I'm Not In Love 10CC Rubber Bullets 10CC Things We Do For Love, The 10CC Wall Street Shuffle 112 & Ludacris Hot & Wet 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac California Love 2 Pac Thugz Mansion 2 Unlimited No Limits 20 Fingers Short Dick Man 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 3 Doors Down Duck & Run 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Its not my time 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors Down Loser 3 Doors Down Road I'm On, The 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 38 Special If I'd Been The One 38 Special Second Chance 3LW I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) 3LW No More 3LW No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) 3LW Playas Gon' Play 3rd Strike Redemption 3SL Take It Easy 3T Anything 3T Tease Me 3T & Michael Jackson Why 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Stairsteps Ooh Child 50 Cent Disco Inferno 50 Cent If I Can't 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent P.I.M.P. (Radio Version) 50 Cent Wanksta 50 Cent & Eminem Patiently Waiting 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 21 Questions 5th Dimension Aquarius_Let the sunshine inB 5th Dimension One less Bell to answer 5th Dimension Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension Up Up & Away 5th Dimension Wedding Blue Bells 5th Dimension, The Last Night I Didn't Get To Sleep At All 69 Boys Tootsie Roll 8 Stops 7 Question -

California Design, 1930-1965: “Living in a Modern Way” CHECKLIST

^ California design, 1930-1965: “living in a modern way” CHECKLIST 1. Evelyn Ackerman (b. 1924, active Culver City) Jerome Ackerman (b. 1920, active Culver City) ERA Industries (Culver City, 1956–present) Ellipses mosaic, c. 1958 Glass mosaic 12 3 ⁄4 x 60 1 ⁄2 x 1 in. (32.4 x 153.7 x 2.5 cm) Collection of Hilary and James McQuaide 2. Acme Boots (Clarksville, Tennessee, founded 1929) Woman’s cowboy boots, 1930s Leather Each: 11 1 ⁄4 x 10 1⁄4 x 3 7⁄8 in. (28.6 x 26 x 9.8 cm) Courtesy of Museum of the American West, Autry National Center 3. Allan Adler (1916–2002, active Los Angeles) Teardrop coffeepot, teapot, creamer and sugar, c. 1957 Silver, ebony Coffeepot, height: 10 in. (25.4 cm); diameter: 9 in. (22.7 cm) Collection of Rebecca Adler (Mrs. Allan Adler) 4. Gilbert Adrian (1903–1959, active Los Angeles) Adrian Ltd. (Beverly Hills, 1942–52) Two-piece dress from The Atomic 50s collection, 1950 Rayon crepe, rayon faille Dress, center-back length: 37 in. (94 cm); bolero, center-back length: 14 in. (35.6 cm) LACMA, Gift of Mrs. Houston Rehrig 5. Gregory Ain (1908–1988, active Los Angeles) Dunsmuir Flats, Los Angeles (exterior perspective), 1937 Graphite on paper 9 3 ⁄4 x 19 1⁄4 in. (24.8 x 48.9 cm) Gregory Ain Collection, Architecture and Design Collection, Museum of Art, Design + Architecture, UC Santa Barbara 6. Gregory Ain (1908–1988, active Los Angeles) Dunsmuir Flats, Los Angeles (plan), 1937 Ink on paper 9 1 ⁄4 x 24 3⁄8 in.